Hardbound Title Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Muslim Nationalism, State Formation and Legal Representations of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan

Politics of Exclusion: Muslim Nationalism, State Formation and Legal Representations of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan by Sadia Saeed A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Sociology) in The University of Michigan 2010 Doctoral Committee: Professor George P. Steinmetz, Chair Professor Howard A. Kimeldorf Associate Professor Fatma Muge Gocek Associate Professor Genevieve Zubrzycki Professor Mamadou Diouf, Columbia University © Sadia Saeed 2010 2 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my parents with my deepest love, respect and gratitude for the innumerable ways they have supported my work and choices. ii Acknowledgements I would like to begin by acknowledging the immense support my parents have given me every step of the way during my (near) decade in graduate school. I have dedicated this dissertation to them. My ammi and baba have always believed in my capabilities to accomplish not only this dissertation but much more in life and their words of love and encouragement have continuously given me the strength and the will to give my research my very best. My father‘s great enthusiasm for this project, his intellectual input and his practical help and advice during the fieldwork of this project have been formative to this project. I would like to thank my dissertation advisor George Steinmetz for the many engaged conversations about theory and methods, for always pushing me to take my work to the next level and above all for teaching me to recognize and avoid sloppiness, caricatures and short-cuts. It is to him that I owe my greatest intellectual debt. -

Zaheeruddin V. State and the Official Persecution of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan

Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality Volume 14 Issue 1 Article 5 June 1996 Enforced Apostasy: Zaheeruddin v. State and the Official Persecution of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan M. Nadeem Ahmad Siddiq Follow this and additional works at: https://lawandinequality.org/ Recommended Citation M. N. Siddiq, Enforced Apostasy: Zaheeruddin v. State and the Officialersecution P of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan, 14(1) LAW & INEQ. 275 (1996). Available at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/lawineq/vol14/iss1/5 Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality is published by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Enforced Apostasy: Zaheeruddin v. State and the Official Persecution of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan M. Nadeem Ahmad Siddiq* Table of Contents Introduction ............................................... 276 I. The Ahmadiyya Community in Islam .................. 278 II. History of Ahmadis in Pakistan ........................ 282 III. The Decision in Zaheerudin v. State ................... 291 A. The Pakistan Court Considers Ahmadis Non- M uslim s ........................................... 292 B. Company and Trademark Laws Do Not Prohibit Ahmadis From Muslim Practices ................... 295 C. The Pakistan Court Misused United States Freedom of Religion Precedent .............................. 299 D. Ordinance XX Should Have Been Found Void for Vagueness ......................................... 314 E. The Pakistan Court Attributed False Statements to Mirza Ghulam Almad ............................. 317 F. Ordinance XX Violates -

Qadiani Problem

THE QADIANI PROBLEM ABUL A/LA MAUDUDI ISLAMIC PUBLICATIONS (PVT.) LIMITED 13-E, Sha.halarn Market, Lahore. (Pakistan) CONTENTS Preface (vii) The Qadiani Problem FS 1 Queer Interpretation of Khatm-e- kabinviwat oF 2 Mirza Ghulam Ahmadis Claim to Prophethood 5 Consequences of claim for Prophethood .•. 6 Religion of Qadianig is. Opposed to Islam IF ., Impiicatioro of New Roligion 8 Demand for Declaring Qadianis as a Separate Minority 4 .. 12 Behaviour of Persons in Power 4 I I. 14 Practice of Heresy amoug Muslim 111 15 Other Sects of Muslims 1•••• 17 Political Ambitions of Qadianie 1•••I 1 El Plan for a Qadiani State in Pakistan 23 Demand for Separation by Majority .. 24 Truth about the Propagation of Islam by Qadianis 27 Loyalty to British Government 20 Motives Behind Propagations r 33 Baic Features of Qadianism Un.animous Demand by all Muslim Sects 40 (VI) APPENDIX I rtaportant Extracts from the First Statement of Maulana Syed Abul Aqa Maududi in the Court of Enquiry ..• 42 The Real Issue and its Background +F1 42 Social Asp-5a 411 44 Economic Aspect 46 Political Aspect .„ • 47 Additional eniuses of Acrimony •••• 'Inevitable Consequence 1.•4 52 Provocation Caused by the Qadianis 64 APPENDIX II Ulnnia's Ame,ndments to the Basic Principles Report APPENDIX 1II Iqbal on Qa.clianism .+. 62 A Letter to the "State.strian" • . P 65 Reply to the Question$ Raised By Pandit .Jawahar L l Nehru Pl• 70 •ALPPENDIX Iv Verdicts of JudiciarY •PM 73 .Tudgcmient P•4. 74 Extracts from Maulana Eyed Abul Gila Maududi' second Statement in the Court of Enquiry ••I The Nature of Demands Concerning the! Qadianis is Political as well no 1Religiou6 ••• 76 THE QADIANI PROBLEM In January 1953, thirty-three leading 1:riama, of Pakistan representing the -various schools of the among Muslim.s assembled in Karachi and formulated their amendments And proposals in regard to the recent constitutional recommendations of the B.P.C. -

Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan

Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan in Pakistan and Militancy Religion a report of the csis program on crisis, conflict, and cooperation Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan a literature review 1800 K Street, NW | Washington, DC 20006 Project Director Tel: (202) 887-0200 | Fax: (202) 775-3199 Robert D. Lamb E-mail: [email protected] | Web: www.csis.org Author Mufti Mariam Mufti June 2012 ISBN 978-0-89206-700-8 CSIS Ë|xHSKITCy067008zv*:+:!:+:! CHARTING our future a report of the csis program on crisis, conflict, and cooperation Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan a literature review Project Director Robert L. Lamb Author Mariam Mufti June 2012 CHARTING our future About CSIS—50th Anniversary Year For 50 years, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has developed practical solutions to the world’s greatest challenges. As we celebrate this milestone, CSIS scholars continue to provide strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart a course toward a better world. CSIS is a bipartisan, nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C. The Center’s 220 full-time staff and large network of affiliated scholars conduct research and analysis and de- velop policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Since 1962, CSIS has been dedicated to finding ways to sustain American prominence and prosperity as a force for good in the world. After 50 years, CSIS has become one of the world’s pre- eminent international policy institutions focused on defense and security; regional stability; and transnational challenges ranging from energy and climate to global development and economic integration. -

The Petty Bourgeoisie in Colonial Canterbury; A

THE PETTY BOURGEOISIE IN COLONIAL CANTERBURY; A STUDY OF THE CANTERBURY WORKING MAN'S POLITICAL PROTECTION AND MUTUAL IMPROVEMENT ASSOCIATION (1865-66), AND THE CANTERBURY FREEHOLD LAND SOCIETY (1866-70) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History in the University of Canterbury by G. R. Wright University of Canterbury 1998 CONTENTS Abbreviations ............................................................................................ 1 Abstract ................................................................................................... 2 Preface .................................................................................................... 3 1. The Petty Bourgeoisie ............................................................................... 7 2. Occupations ......................................................................................... 35 3. Politics ............................................................................................... 71 4. Land ................................................................................................ 1 08 5. Voluntary Participation ........................................................................... 137 Conel u sions ........................................................................................... 161 Appendices ............................................................................................ 163 References ............................................................................................ -

Harpreet Singh

FROM GURU NANAK TO NEW ZEALAND: Mobility in the Sikh Tradition and the History of the Sikh Community in New Zealand to 1947 Harpreet Singh A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History, The University of Otago, 2016. Abstract Currently the research on Sikhs in New Zealand has been defined by W. H. McLeod’s Punjabis in New Zealand (published in the 1980s). The studies in this book revealed Sikh history in New Zealand through the lens of oral history by focussing on the memory of the original settlers and their descendants. However, the advancement of technology has facilitated access to digitised historical documents including newspapers and archives. This dissertation uses these extensive databases of digitised material (combined with non-digital sources) to recover an extensive, if fragmentary, history of South Asians and Sikhs in New Zealand. This dissertation seeks to reconstruct mobility within Sikhism by analysing migration to New Zealand against the backdrop of the early period of Sikh history. Covering the period of the Sikh Gurus, the eighteenth century, the period of the Sikh Kingdom and the colonial era, the research establishes a pattern of mobility leading to migration to New Zealand. The pattern is established by utilising evidence from various aspects of the Sikh faith including Sikh institutions, scripture, literature, and other historical sources of each period to show how mobility was indigenous to the Sikh tradition. It also explores the relationship of Sikhs with the British, which was integral to the absorption of Sikhs into the Empire and continuity of mobile traditions that ultimately led them to New Zealand. -

HISTORY, LAW and LAND Final – MA Thesis

HISTORY, LAW AND LAND: The Languages of Native Policy in New Zealand’s General Assembly, 1858-62 Samuel D. Carpenter 2008 HISTORY, LAW AND LAND: The Languages of Native Policy in New Zealand’s General Assembly, 1858-62 A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History at Massey University, Auckland, New Zealand. Samuel D. Carpenter 2008 ii to J. H. Wright iii Abstract _________________________________________________ This thesis explores the languages of Native policy in New Zealand’s General Assembly from 1858 to 1862. It argues, aligning with the scholarship of Peter Mandler and Duncan Bell, that a stadial discourse, which understood history as a progression from savage or barbarian states to those of civility, was the main paradigm in this period. Other discourses have received attention in New Zealand historiography, namely Locke and Vattel’s labour theory of land and Wakefield’s theory of systematic colonization; but some traditions have not been closely examined, including mid-Victorian Saxonism, the Burkean common law tradition, and the French discourse concerning national character. This thesis seeks to delineate these intellectual contexts that were both European and British, with reference to Imperial and colonial contexts. The thesis comprises a close reading of parliamentary addresses by C. W. Richmond, J. E. FitzGerald and Henry Sewell. iv Acknowledgements __________________________________________________________________ I wish to thank my supervisors Peter Lineham and Michael Belgrave, who have guided me through the challenges of thesis writing, posed many helpful questions and provided research direction throughout the process. Others have provided material and encouragement along the way, including Michael Allen (Waitangi Tribunal), Ruth Barton and Caroline Daley (University of Auckland), John Martin (New Zealand Parliamentary historian), and Sarah Dingle (currently working on a Ph.D. -

Jalsa-UK-Booklet-2019.Pdf

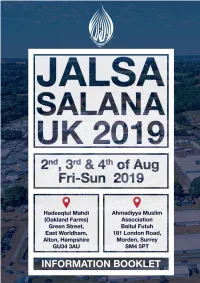

The Jalsa Salana The Annual Convention (Jalsa Salana) of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community UK is a unique event that brings over 35,000 participants from more than 90 countries to in- crease religious knowledge and promote a sense of peace in society. Eminent speakers discuss a range of religious topics and their relevance to contemporary society. Addi- tionally, a number of parliamentarians, civic leaders and diplomats from different countries also address the gather- ing and underline the conventions objective of enhancing unity, understanding and mutual respect. A special feature of this convention is that it is blessed by the presence of His Holiness Hazrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad, the Head of the worldwide Ahmadiyya Muslim Community. He address- es the convention over each of the three days, providing an invaluable insight into religious teachings and how they are a source of guidance for the world today. Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (Peace be upon him) The Founder of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community The Ahmadiyya Muslim Community was founded in 1889 by Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (peace be upon him) of Qadian, India. He claimed under divine guidance to be the Promised Messiah and Imam Mahdi, whose advent was awaited by all the religions of the world. He championed the peaceful teachings of Islam, revived the Faith with a sense of purpose and inspired his followers to build a strong bond with God and to serve humanity with a selfless spirit of compassion and humility. The community is now established in more than 210 coun- tries and it spearheads an international effort to promote the true message of Islam and of service to humanity. -

Powered by TCPDF (

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Dakwah Multi Perspektif: Kajian Filosofis hingga Aksi Penulis: Enjang AS, dkk. Penyunting: Enjang AS Desain Cover: Mang Ozie Penerbit: Madrasah Malem Reboan (MMR) & Pusat Penelitian dan Penerbitan LP2M UIN Sunan Gunung Djati Bandung ISBN: 978-602-51281-7-2 Hak Cipta: pada Penulis Cetakan Pertama: Mei 2018 Dilarang mengutip, memperbanyak, dan menerjemahkan sebagian atau keseluruhan isi buku ini tanpa izin dari Penerbit, kecuali kutipan kecil dengan menyebutkan sumbernya yang layak Pengantar Penyunting PENGANTAR PENYUNTING Tulisan dalam buku ini berasal dari beberapa sumber, terutama yang berasal dari makalah yang telah dipresentasikan dalam diskusi rutin Madrasah Malam Reboan (MMR), yaitu sebuah forum diskusi dosen yang meliputi berbagai keahlian dalam lingkungan UIN Sunan Gunung Djati Bandung. Selain itu, beberapa tulisan lainnya berasal dari makalah yang dimiliki oleh penulis yang belum dipublikasikan tetapi dipandang memiliki topik kajian yang relevan dengan keselu- ruhan topik kajian yang menjadi pembahasan buku ini. Topik pembahasan dalam buku ini, mengkaji persoalan dakwah aktual yang seringkali menjadi wacana diskusi dan pembahasan di tengah masyarakat mulai dari persoalan esensi dan substansi, serta profesionalisme da’i sampai dengan perumusan kebijakan dakwah di tingkat struktural dan teknik dakwah melalui pendekatan konse- ling sebagai bagian dari bentuk dakwah yang dikenal dengan sebut- an irsyad. Bagian awal pada pembahasan buku ini mengkaji tentang dak- wah perspektif filsafat yang disampaikan oleh Dr. Enjang AS, M.Si. yaitu ”Filsafat Dakwah: Sebuah Upaya Keluar dari Kemelut Memper- masalahkan Dakwah”. Pada topik kajian ini, pembahasannya lebih pada bagaimana pemaknaan dan pemahaman dakwah, dan bebe- rapa persoalan yang seringkali terjadi dalam memaknai dakwah. Kajian berikutnya dari Dr. -

An E-Magazine for Nasirat-Ul-Ahmadiyya UK |7Th Edition|

AyeshaAn e-magazine for Nasirat-ul-Ahmadiyya UK |7th Edition| Content 3 Holy Qur’an: Surah Al-Hashr 4 Hadith: Envy 5 Writings of the Promised Messiah (as): The Holy Qur’an is a perfect guidance 6 Huzoor’s (aba) Quotes: Living as a Muslim woman in modern-day society 8 A personal account by Abid Khan Sahib: Europe September-October 2019 part1 10 Books of the Promised Messiah (as): Barahin-e- Ahmadiyya Volume 1 11 Book corner: Hazrat Mariyah Qibtiyya (ra) “Mother of the believers” 12 Career Corner: Specialising as a counselling therapist 13 Travel: Marrakesh 15 Poem: Khilafat 16 Inspiring role model: The slave girl who became the mother of the Holy Prophet Muhammad (saw) 18 Inspiring stories: Hazrat Bilal (ra) 19 Drawing: Mubarak Mosque 20 Recipe: Marbel Cake 21 My amzing body: Eyelashes 23 Nasirat articles: 1) The existence of God 25 2) How I overcame my fear of bees 26 Upcycling: 1) NHS model 2) Surgical Masks 28 Funology: Riddles THE HOLY QUR’AN The Holy Qur’an He is Allah, and there is no God beside Him, the Sovereign, the Holy One, the Source of Peace, the Bestower of Security, the Protector, the Mighty, the Subduer, the Exalted. Holy is Allah far above that which they associate with Him. Commentary God is the King Who is free from every fault, defect, or deficiency. He is the Source of all peace, and the Granter of safety and security. He is Guardian overall, overcoming every power, the Mender of every breakage and the Restorer of every loss; and He is above every need and is the Besought of all. -

Summer Scenes and Flowers: the Beginnings of the New Zealand Christmas Card, 1880-1882

Summer Scenes and Flowers: The Beginnings of the New Zealand Christmas Card, 1880-1882 Peter Gilderdale Keywords: #Christmas traditions #card sending #New Zealand identity #cultural colonisation #photography In October 1883, just as New Zealanders began the annual ritual of buying seasonal tokens of esteem to post overseas, Dunedin’s Evening Star, quoting local photographers the Burton Brothers, posed a question that had exercised immigrants for some years. “Does it not seem folly,” the paper asked “to send back to the Old Country Christmas cards which were manufactured there and exported hither?”1 This was a rhetorical question and the Evening Star went on to respond that “a few years since we should have replied ‘No’; but in view of the experiences of the last two years we say most decidedly, ‘Yes, it is folly.’” The newspaper, clearly, saw the period of 1881 and 1882 as pivotal in the establishment of a small but important industry, the New Zealand Christmas card business.2 My paper examines why these years are significant and what lies behind the debate, identifying a number of early cards and documenting the accompanying developments, primarily via the lens of newspaper advertising. The 1880s Christmas card may not have been an industry on the scale of lamb, but what it lacked in bulk it made up for in symbolism, providing a discrete window into the web of entangled emotional, commercial and design imperatives that attended the way immigrants imagined and constructed this important cultural celebration. 5 For European immigrants to New Zealand, now as well as then, the This newly reframed Christmas provides the context within move to the other side of the world has an unwelcome side-effect. -

GNS Science Report 2013/45

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCE Scott, B.J. 2013. A revised catalogue of Ruapehu volcano eruptive activity: 1830-2012, GNS Science Report 2013/45. 113 p. B.J. Scott, GNS Science, Private Bag 2000, Taupo 3352 © Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited, 2013 ISSN 1177-2425 ISBN 978-1-972192-92-4 CONTENTS ABSTRACT ......................................................................................................................... IV KEYWORDS ........................................................................................................................ IV 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 1 2.0 DATASETS ................................................................................................................ 2 3.0 CLASSIFICATION OF ACTIVITY ............................................................................... 3 4.0 DATA SET COMPLETNESS ...................................................................................... 5 5.0 ERUPTION NARRATIVE ............................................................................................ 6 6.0 LAHARS ................................................................................................................... 20 7.0 DISCUSSION............................................................................................................ 22 8.0 REFERENCES ......................................................................................................... 28 TABLES Table