Signifyin(G) Carl: Nielsen's Music in the Jazz Repertoire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Danish Yearbook of Musicology 36 • 2008 / Dansk Årbog For

102 Danish Yearbook of Musicology • 2008 Still, bringing this much needed research project to fruition is in itself an impressive achievement that lays a solid and valuable foundation on which future research can build and draw inspiration for the telling of further and different stories, and thus keep ‘sounding the horn’ for a past culture that has all but succumbed to silence. Steen Kaargaard Nielsen Christian Munch-Hansen (ed.) By af jazz. Copenhagen Jazz Festival i 30 år. Copenhagen: Thaning & Appel, 2008 257 pp., illus. isbn 978-87-413-0975-0 dkk 299 Frank Büchmann-Møller and Henrik Wolsgaard-Iversen Montmartre. Jazzhuset i St. Regnegade 19, Kbhvn K Odense: Jazzsign & University Press of Southern Denmark, 2008 300 pp., illus. isbn 978-87-7674-297-3 dkk 299 Ole Izard Høyer and Anders H.U. Nielsen Da den moderne jazz kom til byen. En musikkulturel undersøgelse af det danske moderne jazzmiljø 1946–1961. Aalborg: Aalborg Universitetsforlag, 2007 157 pp., illus. isbn 978-87-7307-927-0 dkk 199 With Erik Wiedemann’s extensive work on Danish jazz in the form of his doctoral disser- tation Jazz i Danmark (Jazz in Denmark),1 the formative years of Danish jazz from the twenties until 1950 is well covered. But from that point on, there is no inclusive research material on Danish jazz. However, a great variety of literature on Danish jazz has been pub- lished dealing with this period of time, mostly biographies, coffee table books, and other books written by journalists, musicians, etc. Two of the publications under review here, By af jazz and Montmartre, fall into this category of literature. -

A Little More Than a Year After Suffering a Stroke and Undergoing Physical Therapy at Kessler Institute Buddy Terry Blows His Sax Like He Never Missed a Beat

Volume 39 • Issue 10 November 2011 Journal of the New Jersey Jazz Society Dedicated to the performance, promotion and preservation of jazz. Saxman Buddy Terry made his first appearance with Swingadelic in more than a year at The Priory in Newark on September 30. Enjoying his return are Audrey Welber and Jeff Hackworth. Photo by Tony Mottola. Back in the Band A little more than a year after suffering a stroke and undergoing physical therapy at Kessler Institute Buddy Terry blows his sax like he never missed a beat. Story and photos on page 30. New JerseyJazzSociety in this issue: NEW JERSEY JAZZ SOCIETY Prez Sez . 2 Bulletin Board . 2 NJJS Calendar . 3 Pee Wee Dance Lessons. 3 Jazz Trivia . 4 Editor’s Pick/Deadlines/NJJS Info . 6 Prez Sez September Jazz Social . 51 CD Winner . 52 By Laura Hull President, NJJS Crow’s Nest . 54 New/Renewed Members . 55 hanks to Ricky Riccardi for joining us at the ■ We invite you to mark your calendar for “The Change of Address/Support NJJS/Volunteer/JOIN NJJS . 55 TOctober Jazz Social. We enjoyed hearing Stomp” — the Pee Wee Russell Memorial Stomp about his work with the Louis Armstrong House that is — taking place Sunday, March 4, 2012 at STORIES Buddy Terry and Swingadelic . cover Museum and the effort put into his book — the Birchwood Manor in Whippany. Our Big Band in the Sky. 8 What a Wonderful World. These are the kinds of confirmed groups include The George Gee Swing Dan’s Den . 10 Orchestra, Emily Asher’s Garden Party, and Luna Stage Jazz. -

CHAMPION JACK DUPREE on STORYVILLE RECORDS (The Original Recordings, Incl

‘You Can make it if you try’ Photo: © K. Klüter CHAMPION JACK DUPREE on STORYVILLE RECORDS (The original recordings, incl. various re-issues). William Thomas Dupree, born, c. July 10, 1910 in New Orleans and passed away, January 21, 1992 in Hannover. Compiled by Allan Stephensen. Updated, March 17, 2010. Note: On the last pages you will find the late, Arne Svensson’s story about his first meeting with Dupree. * CHAMPION JACK DUPREE (p,vo). Copenhagen, Tuesday, December 29, 1959. 2:09 Gravier Street Rag Storyville SLP 213, 6.28443 (dbl), STCD 8030 2:31 Old Woman Blues Storyville STCD 8044 3:18 Roll Me Over And Roll Me Slow Storyville SLP 107, Atlantic 8056, 1022, CD 7567925302, Collectables CD 6818 2:52 Daybreak Stomp Storyville SLP 107, Atlantic 8056, 1022, CD 7567925302, Collectables CD 6818, WEA (UK) 954836956-2 2:47 That’s All Right Storyville SLP 107, Atlantic 8056, 1022, CD 7567925302, Collectables CD 6818 3:34 Reminiscin’ With Champion Jack Dupree Same issues 2:45 I Had A Dream Storyville SLP 107, Atlantic 8056, 1022, CD 7567925302, Collectables CD 6818, WEA (UK) 954836956-2 2:57 House Rent Party Storyville SLP 107, Atlantic 8056, 1022, CD 7567925302, Collectables CD 6818 2:39 Snaps Drinking Woman Same issues 3:23 One Sweet Letter From You Storyville SLP 107, Atlantic 7-8640 (7”), 8056, 1022, CD 7567925302, Collectables CD 6818 2:27 Johnson Street Boogie Woogie Storyville SLP 107, Atlantic 8056, 1022, CD 7567925302, Collectables CD 6818 3:01 Misery Blues Storyville SLP 107, Atlantic 7-8640 (7”), 8056, 1022, CD 7567925302, Collectables CD 6818 6:15 Misery Blues (alternate take) Unissued 2:56 New Vicksburg Blues Storyville SLP 107, Atlantic 8056, 1022, CD 7567925302, Collectables CD 6818 3:03 New Vicksburg Blues (alternate take) Storyville STCD 8045 2:34 When Things Go Wrong Storyville SLP 107, Atlantic 8056, 1022, CD 7567925302, Collectables CD 6818, Blues Encore CD 52029 Notes: Echo added to vocals. -

Jakob Bro (1978) Is a Danish Guitar Player and Composer Living in Copenhagen, Denmark. He Is a Former Member of Paul Motian &

Jakob Bro (1978) is a Danish guitar player and composer living in Copenhagen, Denmark. He is a former member of Paul Motian & The Electric Bebop Band (Garden of Eden, ECM - 2006) and a current member of Tomasz Stanko’s Dark Eyes Quintet (Dark Eyes, ECM - 2009). He has released 12 records as a bandleader including musicians like Lee Konitz, Bill Frisell, Paul Motian, Kenny Wheeler, Paul Bley, Chris Cheek, Thomas Morgan, Ben Street, Mark Turner, Kurt Rosenwinkel, Andrew D’Angelo, Chris Speed, George Garzone, Oscar Noriega, David Virelles, Jon Christensen and many more. He has toured in Japan, China, South Korea, Australia, Brazil, Argentina, Columbia, South Africa, USA and most of Europe Jakob Bro is currently leading a trio with Joey Baron and Thomas Morgan. This trio recorded a new album for ECM Records in November 2015 set to come out in the near future. Also he is working with Palle Mikkelborg and with Bro/Knak, a collaboration with the Danish electronica producer Thomas Knak (Opiate). A new project with Danish/British trumpet player Jakob Buchanan, Thomas Morgan and music for choir is also under way. Jakob Bro has received 6 Danish Music Awards and has been accepted into Jazz Denmark’s Hall of Fame. In 2009 and 2013 he received JazzSpecial’s price for Danish Jazz Record of the Year (Balladeering & December Song) and in 2012 he received the DJBFA honorary award. The year after, in 2013 he received both the ”Composer of the Year” Award from Danish Music Publishers Association (the price is named after Danish classical composer Carl Nielsen) and The Jazznyt Price founded by Niels Overgaard. -

John Clark Brian Charette Finn Von Eyben Gil Evans

NOVEMBER 2016—ISSUE 175 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM JOHN BRIAN FINN GIL CLARK CHARETTE VON EYBEN EVANS Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East NOVEMBER 2016—ISSUE 175 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : John Clark 6 by anders griffen [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : Brian Charette 7 by ken dryden General Inquiries: [email protected] On The Cover : Maria Schneider 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : Finn Von Eyben by clifford allen Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : Gil Evans 10 by eric wendell [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : Setola di Maiale by ken waxman US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] Festival Report Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, CD Reviews Stuart Broomer, Thomas Conrad, 14 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Philip Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, Miscellany 33 Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Event Calendar 34 Ken Micallef, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Ken Waxman Contributing Writers Robert Bush, Laurel Gross, George Kanzler, Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman It is fascinating that two disparate American events both take place in November with Election Contributing Photographers Day and Thanksgiving. -

Wild Bill Davison Farfar's Blues Mp3, Flac, Wma

Wild Bill Davison Farfar's Blues mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Farfar's Blues Country: Switzerland Released: 1986 MP3 version RAR size: 1148 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1815 mb WMA version RAR size: 1476 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 415 Other Formats: FLAC VOX WMA ASF AIFF VOC AU Tracklist A1 I'm Confessin' That I Love You A2 As Long As I Live A3 A Cottage For Sale A4 I Never Knew A5 Farfar's Blues A6 Way Down Yonder In New Orleans B1 Blues My Naughtie Sweetie Gives To Me B2 Blue And Sentimental B3 Our Love Is Here To Stay B4 Tishomingo Blues B5 You're Lucky To Me Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Storyville Records AB Copyright (c) – Storyville Records AB Credits Banjo – Bjarne Liller* (tracks: A6, B1) Bass – Jens Sølund Clarinet – Jørgen Svare Cornet – Wild Bill Davison Drums – Knud Ryskov Madsen* Guitar – Lars Blach Liner Notes – Jørgen Frigård Piano – Jørn Jensen Saxophone – Bent Jædig (tracks: A3, A5, B5) Trombone – Arne Bue Jensen Vocals – Wild Bill Davison Notes Cover info: Recorded Copenhagen 1974 - 1977 (C) 1981 (P) 1977 ... Printed in USA Label info: (P) + (C) 1986 Storyville AB Barcode and Other Identifiers Label Code: SLP 4029 A Label Code: SLP 4029 B Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Wild Bill Davison & Wild Bill Davison & Papa SLP 4029 Papa Bue's Viking Bue's Viking Jazzband* - Storyville SLP 4029 Switzerland 1986 Jazzband* Farfar's Blues (LP, Comp) Wild Bill Davison & Papa Wild Bill Davison & Bue's Viking Jazzband* - Wild SLP-4029 Papa Bue's Viking Storyville SLP-4029 US 1981 Bill Davison & Papa Bue's Jazzband* Viking Jazzband (LP, Comp) Related Music albums to Farfar's Blues by Wild Bill Davison Wild Bill Davison With Eddie Condon's All Stars - Wild Bill Davison With Eddie Condon's All Stars Wild Bill Davison - But Beautiful Wild Bill Davison - "Pretty Wild" and "With Strings Attached" Wild Bill Davison & The All Star Stompers - This Is Jazz Vol. -

Cash Box, Music Page 39 March 26, 1960

) ) he Cash Box, Music Page 39 March 26, 1960 DENMARK’S SCANDINAVIA Best Sellers First Swedish recordings from the recent San Remo festival are on sale 1 Klaus-Jorgen ;re. All the top tunes from the Italian song festival seem to have reached TOP (Grethe Sonck/ Sonet) ie Swedish market immediately after the festival. Of the many recordings Swedish song is milable here one is by Palette Records, headed by Henry Fox, which just 2 Marina Scandinavian leased “Romantica i San Remo” including Swedish recordings of the tunes (Raquel Rastenni/HMV) lomantica”, “Libero”, “Splende l’Arcobaleno” and “Gridare di Gioia”. Livin’ Doll ike Mossmerg, a new name here sings “Romantica”. 3 (Cliff Richard/Columbia) Talents Dj There seems to be great interest in the forthcoming Eurovision Song- 4 The Three Bells estival to be televised from Royal Festival Hall in London on March 29th. (The Browns/RCA) PAPA BUE’S VIKINGS is expected that most of the Swedish music publishers, as well as repre- 5 Schlafe mein Prinzchen intatives of all the leading record companies, will be among the public in BLUE BOYS -BORIS AND HIS (Papa Bue’s Viking Jazzband/ s ondon when the songs are aired. Storyville) JAILERS -LISE REINAU — SAM From Denmark we hear that Hede Nielsens Fabrikker has taken over the 6 Oh, Quelle Nuit i; anish representation of Warner Bros., the American label. Hede Nielsens PAYNE -BENGT ARNE WALLIN (Trumpet Boy/Philips) so handles RCA Victor in Denmark. 7 Charlie Brown Recent discovery on Danish record market is Frede Heiselberg, a singer (Blue Boys/Sonet) ho is on the way to the top with his debut recox’d, a Danish version of 8 Morgen VIorgen” waxed by Karusell in Copenhagen. -

Bévort 3 Feat. Mads Kjølby on Guitar

Photo by: Nanja Pontoppidan Bévort 3 feat. Mads Kjølby on guitar “Trio Temptations”, Gateway Music January 2014. Pernille Bévort: Tenor- and soprano saxophone; Mads Kjølby: guitar; Morten Ankarfeldt: Bass; Espen Laub von Lillienskjold: Drums A lot of the great tenor players have made the trio format a classic within jazz: Sonny Rollins, Joe Lovano and Joe Henderson, just to mention a few. It’s always a great challenge to perform with no chord instrument in the line-up, since the musicians can imply the chords in their playing in many ways and they need to communicate very carefully with each other. This very open format also gives the musicians a lot of possibilities to interpret and to change direction in the music, together and with short notice. This makes it a very fun “playground” to work within, and it is also interesting for the listener to follow the ride. “Trio Temptations” is the first Cd released with this Danish trio and it documents the work of 3 experienced jazz musicians. One can hear the close communication and the joyful, energetic collaboration between the 3 performers. They play with energy and curiosity - always ready to take a chance. On several occasions they have invited the wonderful guitar player Mads Kjølby as featured guest. This adds even more colours to the music. Band leader and saxophonist Pernille Bévort is an experienced musician on the Danish jazz scene. Apart from working with small ensembles, Bévort has performed with several professional Big Bands in Denmark during the last decade: The Ernie Wilkins Almost Big Band, The Danish Radio Big Band and the Aarhus Jazz Orchestra (Klüver’s Big Band) among others. -

The Fragility of Faroese Jazz

The Fragility of Faroese Jazz Final report MMuS/NAIP: Arnold Ludvig 2019 Instructor: Erik Deluca, PhD IUA - LOK020JTM: NAIP Professional Integration II April 25th 2019 ABSTRACT In this essay, I share my research on the history of Jazz in the Faroe Islands. This research includes participant observation and interviews with interlocutors. This essay concludes with a description of my current artistic practice and how it is inextricably linked to the Faroese jazz scene. It is my hope that this essay will stimulate a discussion amongst musicians, composers, historians, journalists, and audience members about the evolution and development of jazz in the Faroe Islands. ____________________________ TABLE OF CONTENT ABSTRACT 1 TABLE OF CONTENT 1 INTRODUCTION 2 THE AFRICAN DIASPORA 3 EARLY JAZZ IN THE FAROE ISLANDS - 1920-30 4 PERLAN 8 FOREIGN GUEST MUSICIANS 10 TUTL RECORDS - THE PERLAN SOUND 12 THE MAYOR’S BROKEN PROMISE 14 PHOENIX RISING 16 TÓRSHAVNAR JAZZ, FÓLKA OG BLUES FESTIVAL (1984-2003) 17 FAROESE JAZZ AND ITS CHALLENGES 19 JAZZ IN THE FAROE ISLANDS 2019 22 BLUEPRINT - PERLAN TO PRESENT 23 PRESENT TO FUTURE - QUINTET ALBUM PROJECT 25 RESEARCH ON FAROESE JAZZ HISTORY CONTINUED 27 BIOGRAPHY 28 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT 29 BIBLIOGRAPHY 30 DISCOGRAPHY 31 1 INTRODUCTION A pearl is a hard lustrous mass formed within the shell of a pinctada oyster. These pearls are often referred to as gems (precious stones). Interestingly, an important history of jazz in the Faroe Islands is contained within a club, in Tórshavn (the capital city of the Faroe Islands) called PERLAN (The Pearl).1 This jazz gem cultivated an important era for the genre in the Faroe Islands. -

Chicago Jazz Festival Spotlights Hometown

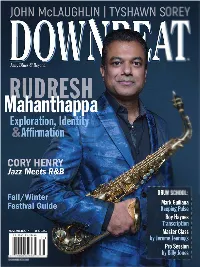

NOVEMBER 2017 VOLUME 84 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Managing Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Markus Stuckey Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Hawkins Editorial Intern Izzy Yellen ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Kevin R. Maher 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, -

The Genesis of King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band Gene H

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Music Faculty Publications Music Fall 1994 The Genesis of King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band Gene H. Anderson University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/music-faculty-publications Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Anderson, Gene H. "The Genesis of King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band." American Music 12, no. 3 (Fall 1994): 283-303. doi:10.2307/ 3052275. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Music Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GENE ANDERSON The Genesis of King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band On Thursday, April 5, 1923, the Creole Jazz Band stopped off in Rich- mond, Indiana, to make jazz history. The group included Joe Oliver and Louis Armstrong (comets), Johnny Dodds (clarinet), Honor4 Dutrey (trombone), Bill Johnson (banjo), Lil Hardin (piano), and Warren"Baby" Dodds (drums) (fig. 1). For the rest of that day and part of the next, the band cut nine portentous sides, in sessions periodically interrupted by the passage of trains running on tracks near the Gennett studios where the recording took place. By year's end, sessions at OKeh and Columbia Records expanded the number of sides the band made to thirty-nine, creating the first recordings of substance by an African American band--the most significant corpus of early recorded jazz - surpassing those of such white predecessors as the Original Dixieland Jazz Band and the New Orleans Rhythm Kings. -

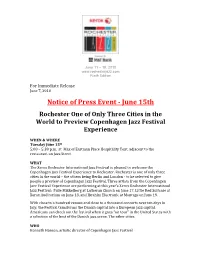

Notice of Press Event - June 15Th

June 11 – 19, 2010 www.rochesterjazz.com Ninth Edition For Immediate Release June 7, 2010 Notice of Press Event - June 15th Rochester One of Only Three Cities in the World to Preview Copenhagen Jazz Festival Experience WHEN & WHERE Tuesday June 15th 5:00 – 5:30 p.m. at Max of Eastman Place Hospitality Tent, adjacent to the restaurant on Jazz Street WHAT The Xerox Rochester International Jazz Festival is pleased to welcome the Copenhagen Jazz Festival Experience to Rochester. Rochester is one of only three cities in the world – the others being Berlin and London - to be selected to give people a preview of Copenhagen Jazz Festival. Three artists from the Copenhagen Jazz Festival Experience are performing at this year’s Xerox Rochester International Jazz Festival: Palle Mikkelborg at Lutheran Church on June 17, Little Red Suitcase at Xerox Auditorium on June 18, and Ibrahim Electronic at Montage on June 19. With close to a hundred venues and close to a thousand concerts over ten days in July, the Festival transforms the Danish capital into a European jazz capital. Americans can check out the festival when it goes “on tour” in the United States with a selection of the best of the Danish jazz scene. The other cities WHO Kenneth Hansen, artistic director of Copenhagen Jazz Festival RSVP Please RSVP to Jean Dalmath at [email protected] if you plan on attending the press event. Sponsors Xerox, City of Rochester, M&T Bank, Monroe County Executive Maggie Brooks, the Democrat and Chronicle, Eastman School of Music, Rochester Plaza Hotel, Brooklyn Brewery, Michelob, Spaten Beer, Verizon Wireless, The Community Foundation, 13WHAM TV, Rochester General Health System, Visit Rochester, Mercury Print Productions, SUNY Brockport, ADMAR, Presentation Source, AirTran, DownBeat Magazine, Constellation, Max of Eastman Place, House of Guitars, MidTown Athletic Club.