Recognizing the Assemblage: Palestinian Bedouin of the Naqab

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction Really, 'Human Dust'?

Notes INTRODUCTION 1. Peck, The Lost Heritage of the Holocaust Survivors, Gesher, 106 (1982) p.107. 2. For 'Herut's' place in this matter, see H. T. Yablonka, 'The Commander of the Yizkor Order, Herut, Shoa and Survivors', in I. Troen and N. Lucas (eds.) Israel the First Decade, New York: SUNY Press, 1995. 3. Heller, On Struggling for Nationhood, p. 66. 4. Z. Mankowitz, Zionism and the Holocaust Survivors; Y. Gutman and A. Drechsler (eds.) She'erit Haplita, 1944-1948. Proceedings of the Sixth Yad Vas hem International Historical Conference, Jerusalem 1991, pp. 189-90. 5. Proudfoot, 'European Refugees', pp. 238-9, 339-41; Grossman, The Exiles, pp. 10-11. 6. Gutman, Jews in Poland, pp. 65-103. 7. Dinnerstein, America and the Survivors, pp. 39-71. 8. Slutsky, Annals of the Haganah, B, p. 1114. 9. Heller The Struggle for the Jewish State, pp. 82-5. 10. Bauer, Survivors; Tsemerion, Holocaust Survivors Press. 11. Mankowitz, op. cit., p. 190. REALLY, 'HUMAN DUST'? 1. Many of the sources posed problems concerning numerical data on immi gration, especially for the months leading up to the end of the British Mandate, January-April 1948, and the first few months of the state, May August 1948. The researchers point out that 7,574 immigrant data cards are missing from the records and believe this to be due to the 'circumstances of the times'. Records are complete from September 1948 onward, and an important population census was held in November 1948. A parallel record ing system conducted by the Jewish Agency, which continued to operate after that of the Mandatory Government, provided us with statistical data for immigration during 1948-9 and made it possible to analyse the part taken by the Holocaust survivors. -

Aliyah and Settlement Process?

Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel HBI SERIES ON JEWISH WOMEN Shulamit Reinharz, General Editor Joyce Antler, Associate Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor The HBI Series on Jewish Women, created by the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute, pub- lishes a wide range of books by and about Jewish women in diverse contexts and time periods. Of interest to scholars and the educated public, the HBI Series on Jewish Women fills major gaps in Jewish Studies and in Women and Gender Studies as well as their intersection. For the complete list of books that are available in this series, please see www.upne.com and www.upne.com/series/BSJW.html. Ruth Kark, Margalit Shilo, and Galit Hasan-Rokem, editors, Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel: Life History, Politics, and Culture Tova Hartman, Feminism Encounters Traditional Judaism: Resistance and Accommodation Anne Lapidus Lerner, Eternally Eve: Images of Eve in the Hebrew Bible, Midrash, and Modern Jewish Poetry Margalit Shilo, Princess or Prisoner? Jewish Women in Jerusalem, 1840–1914 Marcia Falk, translator, The Song of Songs: Love Lyrics from the Bible Sylvia Barack Fishman, Double or Nothing? Jewish Families and Mixed Marriage Avraham Grossman, Pious and Rebellious: Jewish Women in Medieval Europe Iris Parush, Reading Jewish Women: Marginality and Modernization in Nineteenth-Century Eastern European Jewish Society Shulamit Reinharz and Mark A. Raider, editors, American Jewish Women and the Zionist Enterprise Tamar Ross, Expanding the Palace of Torah: Orthodoxy and Feminism Farideh Goldin, Wedding Song: Memoirs of an Iranian Jewish Woman Elizabeth Wyner Mark, editor, The Covenant of Circumcision: New Perspectives on an Ancient Jewish Rite Rochelle L. -

Israel and the Occupied Territories 2014 Human

ISRAEL 2014 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Israel is a multi-party parliamentary democracy. Although it has no constitution, the parliament, the unicameral 120-member Knesset, has enacted a series of “Basic Laws” that enumerate fundamental rights. Certain fundamental laws, orders, and regulations legally depend on the existence of a “State of Emergency,” which has been in effect since 1948. Under the Basic Laws, the Knesset has the power to dissolve the government and mandate elections. The nationwide Knesset elections in January 2013, considered free and fair, resulted in a coalition government led by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Security forces reported to civilian authorities. (An annex to this report covers human rights in the occupied territories. This report deals with human rights in Israel and the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights.) During the year a number of developments affected both the Israeli and Palestinian populations. From July 8 to August 26, Israel conducted a military operation designated as Operation Protective Edge, which according to Israeli officials responded to increases in the number of rockets deliberately fired from Gaza at Israeli civilian areas beginning in late June, as well as militants’ attempts to infiltrate the country through tunnels from Gaza. According to publicly available data, Hamas and other militant groups fired 4,465 rockets and mortar shells into Israel, while the government conducted 5,242 airstrikes within Gaza and a 20-day military ground operation in Gaza. According to the United Nations, the operation killed 2,205 Palestinians. The Israeli government estimated that half of those killed were civilians and half were combatants, according to an analysis of data, while the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs recorded 1,483 civilian deaths--more than two-thirds of those killed--including 521 children and 283 women; 74 persons in Israel were killed, among them 67 combatants, six Israeli civilians, and one Thai civilian. -

Republication, Copying Or Redistribution by Any Means Is

Republication, copying or redistribution by any means is expressly prohibited without the prior written permission of The Economist The Economist April 5th 2008 A special report on Israel 1 The next generation Also in this section Fenced in Short-term safety is not providing long-term security, and sometimes works against it. Page 4 To ght, perchance to die Policing the Palestinians has eroded the soul of Israel’s people’s army. Page 6 Miracles and mirages A strong economy built on weak fundamentals. Page 7 A house of many mansions Israeli Jews are becoming more disparate but also somewhat more tolerant of each other. Page 9 Israel at 60 is as prosperous and secure as it has ever been, but its Hanging on future looks increasingly uncertain, says Gideon Licheld. Can it The settlers are regrouping from their defeat resolve its problems in time? in Gaza. Page 11 HREE years ago, in a slim volume enti- abroad, for Israel to become a fully demo- Ttled Epistle to an Israeli Jewish-Zionist cratic, non-Zionist state and grant some How the other fth lives Leader, Yehezkel Dror, a veteran Israeli form of autonomy to Arab-Israelis. The Arab-Israelis are increasingly treated as the political scientist, set out two contrasting best and brightest have emigrated, leaving enemy within. Page 12 visions of how his country might look in a waning economy. Government coali- the year 2040. tions are fractious and short-lived. The dif- In the rst, it has some 50% more peo- ferent population groups are ghettoised; A systemic problem ple, is home to two-thirds of the world’s wealth gaps yawn. -

The Bedouin Population in the Negev

T The Since the establishment of the State of Israel, the Bedouins h in the Negev have rarely been included in the Israeli public e discourse, even though they comprise around one-fourth B Bedouin e of the Negev’s population. Recently, however, political, d o economic and social changes have raised public awareness u i of this population group, as have the efforts to resolve the n TThehe BBedouinedouin PPopulationopulation status of the unrecognized Bedouin villages in the Negev, P Population o primarily through the Goldberg and Prawer Committees. p u These changing trends have exposed major shortcomings l a in information, facts and figures regarding the Arab- t i iinn tthehe NNegevegev o Bedouins in the Negev. The objective of this publication n The Abraham Fund Initiatives is to fill in this missing information and to portray a i in the n Building a Shared Future for Israel’s comprehensive picture of this population group. t Jewish and Arab Citizens h The first section, written by Arik Rudnitzky, describes e The Abraham Fund Initiatives is a non- the social, demographic and economic characteristics of N Negev profit organization that has been working e Bedouin society in the Negev and compares these to the g since 1989 to promote coexistence and Jewish population and the general Arab population in e equality among Israel’s Jewish and Arab v Israel. citizens. Named for the common ancestor of both Jews and Arabs, The Abraham In the second section, Dr. Thabet Abu Ras discusses social Fund Initiatives advances a cohesive, and demographic attributes in the context of government secure and just Israeli society by policy toward the Bedouin population with respect to promoting policies based on innovative economics, politics, land and settlement, decisive rulings social models, and by conducting large- of the High Court of Justice concerning the Bedouins and scale social change initiatives, advocacy the new political awakening in Bedouin society. -

Strateg Ic a Ssessmen T

Strategic Assessment Assessment Strategic Volume 22 | No. 2 | July 2019 Volume 22 Volume Legislative Initiatives to Change the Judicial System are Unnecessary Bell Yosef Arab Society and the Elections for the 21st and 22nd Knesset | No. 2 No. Ephraim Lavie, Mursi Abu Mokh, and Meir Elran The Delegitimization of Peace Advocates in Israeli Society | July 2019 Gilead Sher, Naomi Sternberg, and Mor Ben-Kalifa Hamas and Technology: One Step Forward, Two Steps Back Aviad Mendelboim and Liran Antebi Civilian Control of the Military with Regard to Value-Based Issues in a World of Hybrid Conflicts Kobi Michael and Carmit Padan Polarization in the European Union and the Implications for Israel: The Case of the Netherlands J. M. Caljé Saudi-Pakistan Relations: More than Meets the Eye Yoel Guzansky Israel-East Africa Relations Yaron Salman Strategic ASSESSMENT Volume 22 | No. 2 | July 2019 Note from the Editor | 3 Legislative Initiatives to Change the Judicial System are Unnecessary | 7 Bell Yosef Arab Society and the Elections for the 21st and 22nd Knesset | 19 Ephraim Lavie, Mursi Abu Mokh, and Meir Elran The Delegitimization of Peace Advocates in Israeli Society | 29 Gilead Sher, Naomi Sternberg, and Mor Ben-Kalifa Hamas and Technology: One Step Forward, Two Steps Back | 43 Aviad Mendelboim and Liran Antebi Civilian Control of the Military with Regard to Value-Based Issues in a World of Hybrid Conflicts| 57 Kobi Michael and Carmit Padan Polarization in the European Union and the Implications for Israel: The Case of the Netherlands | 71 J. M. Caljé Saudi-Pakistan Relations: More than Meets the Eye | 81 Yoel Guzansky Israel-East Africa Relations | 93 Yaron Salman Strategic ASSESSMENT The purpose of Strategic Assessment is to stimulate and enrich the public debate on issues that are, or should be, on Israel’s national security agenda. -

Future of the AUMF: Lessons from Israel's Supreme Court Emily Singer Hurvitz American University Washington College of Law

American University National Security Law Brief Volume 4 | Issue 2 Article 3 2014 Future of the AUMF: Lessons From Israel's Supreme Court Emily Singer Hurvitz American University Washington College of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/nslb Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Hurvitz, Emily Singer. "Future of the AUMF: Lessons From Israel's Supreme Court." National Security Law Brief 4, no. 2 (2014): 43-75. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University National Security Law Brief by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 42 NATIONAL SECURITY LAW BRIEF Vol. 4, No. 2 Vol. 4, No. 2 Future of the AUMF 43 FUTURE OF THE AUMF: LESSONS FROM ISRAEL’S SUPREME COURT Emily Singer Hurvitz1 “Judges in modern democracies should protect democracy both from terrorism and from the means the state wishes to use to fght terrorism.”2 Introduction Following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, Congress enacted the Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF) to give the President power to use military force specifcally against the people and organizations connected to the terrorist attacks: al-Qaeda and the Taliban.3 Some would argue that Congress’s goals in enacting the AUMF have been met—al-Qaeda -

Konstantinos Papastathis Ruth Kark

Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies 40 (2) 264À282 The Politics of church land administration: the Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem in late Ottoman and Mandatory Palestine, 1875–1948 Konstantinos Papastathis University of Luxembourg [email protected] Ruth Kark The Hebrew University of Jerusalem [email protected] This article follows the course of the prolonged land dispute within the Orthodox Church of Jerusalem between the Greek religious establishment and the local Arab laity from the late Ottoman period to the end of the British Mandate (1875–1948). The article examines state policies in relation to Church-owned property and assesses how the administration of this property affected the inter-communal relationship. It is argued that both the Ottoman and the British authorities effectively adopted a pro- Greek stance, and that government refusal of the local Arab lay demands was predominantly predicated on regional and global political priorities. Keywords: Vakf administration; Late Ottoman Palestine; British Mandate; Orthodox Church; intra-communal relations Introduction The Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem is institutionally structured as a monastic Brotherhood, having as its primary duty the protection of Orthodox rights over the Christian Holy Places. The alleged lack of pastoral interest in the laity, coupled with prevention of the admission of Arab clergy to the religious bureaucracy by the dominant Greek ecclesiastics, led from the nineteenth century onwards to a significant internal polarization between the two groups. The Arab nation-building process, the Greek We are grateful to Professor Peter Mackridge and the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions. We also gratefully acknowledge the participants of the 21st International Congress of the Comité International des Études Pré-Ottomanes et Ottomanes (CIEPO) (Budapest, 2014) for their substantial critique and valuable feedback. -

BR IFIC N° 2779 Index/Indice

BR IFIC N° 2779 Index/Indice International Frequency Information Circular (Terrestrial Services) ITU - Radiocommunication Bureau Circular Internacional de Información sobre Frecuencias (Servicios Terrenales) UIT - Oficina de Radiocomunicaciones Circulaire Internationale d'Information sur les Fréquences (Services de Terre) UIT - Bureau des Radiocommunications Part 1 / Partie 1 / Parte 1 Date/Fecha 30.09.2014 Description of Columns Description des colonnes Descripción de columnas No. Sequential number Numéro séquenciel Número sequencial BR Id. BR identification number Numéro d'identification du BR Número de identificación de la BR Adm Notifying Administration Administration notificatrice Administración notificante 1A [MHz] Assigned frequency [MHz] Fréquence assignée [MHz] Frecuencia asignada [MHz] Name of the location of Nom de l'emplacement de Nombre del emplazamiento de 4A/5A transmitting / receiving station la station d'émission / réception estación transmisora / receptora 4B/5B Geographical area Zone géographique Zona geográfica 4C/5C Geographical coordinates Coordonnées géographiques Coordenadas geográficas 6A Class of station Classe de station Clase de estación Purpose of the notification: Objet de la notification: Propósito de la notificación: Intent ADD-addition MOD-modify ADD-ajouter MOD-modifier ADD-añadir MOD-modificar SUP-suppress W/D-withdraw SUP-supprimer W/D-retirer SUP-suprimir W/D-retirar No. BR Id Adm 1A [MHz] 4A/5A 4B/5B 4C/5C 6A Part Intent 1 114095204 AUS 3.1665 MANGALORE AUS 146°E04'37'' 26°S47'13'' AM 1 ADD 2 114095209 -

Conference Conveners: Officiated By: Incumbent Office-Holders

Conference Conveners: Prof. Uriel Reichman Maj. Gen. (res.) Amos Gilead President & Founder, IDC Herzliya Executive Director, Institute for Policy and Strategy, and Chairman of the Annual Herzliya Conference Series, IDC Herzliya Officiated by: H.E. Reuven (Ruvi) Rivlin President of the State of Israel Photo: Spokesperson unit of the President of Israel Incumbent Office-Holders Commissioner Roni Alsheikh MK Naftali Bennett MK Yuli-Yoel Edelstein General Commissioner of the Israel Police Minister of Education and Minister Speaker of the Knesset of Diaspora Affairs Lt. Gen. Gadi Eisenkot H.E. Khairat Hazem Mr. Moshe Kahlon IDF Chief of the General Staff Ambassador of Egypt to Israel Minister of Finance MK Israel Katz Rabbi David Lau Mr. Avigdor Liberman Minister of Intelligence and Transport Chief Rabbi of Israel Minister of Defense Hon. Brett McGurk Dr. Antonio Missiroli Hon. Judge (ret.) Joseph H. Shapira Special Presidential Envoy for the Global Assistant Secretary General of NATO for State Comptroller and Ombudsman Coalition to Counter ISIL, Emerging Security Challenges U.S. Department of State Prof. Dmitry Adamsky Lt. Gen. (ret.) Orit Adato Mr. Elliott Abrams Lauder School of Government, Diplomacy and Founder & Managing Director, Adato Senior Fellow, Council on Foreign Relations Strategy, IDC Herzliya Consulting; Former Commissioner of the Israel Prison Service and Former Commander of IDF Women Corp Photo: Kaveh Sardari Mr. Yaacov Agam Mr. Simon Alfasi Prof. Graham Allison Sculptor and Experimental Artist Mayor of Yokneam Douglas Dillon Professor of Government, Harvard Kennedy School Ms. Elah Alkalay Col. (res.) Dov Amitay Ms. Anat Asraf Hayut VP for Business Development President, Farmers' Federation of Israel National Elections’ Supervisor, IBI Investment House Ministry of Interior Prof. -

Space and Place: North African Jewish Widows in Late-Ottoman Palestine*

Journal of Women of the Middle East and the Islamic World 10 (2012) 37–58 brill.nl/hawwa Space and Place: North African Jewish Widows in Late-Ottoman Palestine* Michal Ben Ya’akov Efrata College of Education Jerusalem, Israel [email protected] Abstract During the nineteenth century, the number of Jews in Jerusalem soared, including Jews in the North African Jewish community, which witnessed a significant growth spurt. Within the Jewish community, the number of widows, both young and old, was significant— approximately one-third of all adult Jews. This paper focuses on the spatial organization and residential patterns of Maghrebi Jewish widows and their social significance in nineteenth-century Jerusalem. Although many widows lived with their families, for other widows, without family in the city, living with family was not an option and they lived alone. By sharing rented quarters with other widows, some sought companionship as well as to ease the financial burden; others had to rely on communal support in shelters and endowed rooms. Each of these solutions reflected communal and religious norms regarding women in general, and widows in particular, ranging from marginalization and rejection to sincere concern and action. Keywords Widows, Jews, North African Jews, Moroccan Jews, Palestine, Jerusalem In the nineteenth century, an enormous number of Jewish widows— approximately one-third of all adult Jews—lived in Palestine. This social and demographic phenomenon was characteristic of the Jewish communi- ties in the Holy Land for several centuries,1 with the proportion of Ashkenazi * Work for this study was undertaken with the generous support of the Hadassah Research Institute on Jewish Women at Brandeis University and the Maurice Amado Research Fund from UCLA. -

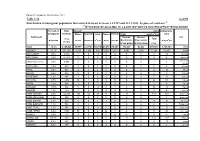

1.16 לוח Table 1.16 Distribution of Immigrant Population That Arrived in Israel Between 1.1.1989 and 31.12.2011, by Place Of

Ruppin Yearbook on Immigration, 2012 לוח Table 1.16 1.16 Distribution of immigrant population that arrived in Israel between 1.1.1989 and 31.12.2011, by place of residence(1) )1( התפלגות אוכלוסיית עולים שעלו ארצה בין התאריכים 1.1.1989 עד 31.12.2011, לפי מקום מגורים ,Immigrants מתוכם: :Percent of Total Thereof total בריה"מ לשעבר immigrants residents Others Argentin USA France Ethiopi FSU ישוב :Settlement a a Thereof: Thereof Total סה"כ סה"כ עולים Bucharians Caucasians אתיופים צרפת ארה"ב ארגנטינה אחרים אחוז עולים תושבים סה"כ מתוכם קווקזים מתוכם בוכרים סה"כ Total 14.3% 8,185,568 99,777 22,740 53,219 41,876 70,001 110,001 52,862 879,569 1,167,182 אשדוד ASHDOD 32.1% 237,285 4,232 1,408 640 5,005 3,574 5,801 1,966 61,398 76,257 אבו גוש ABU GHOSH 0.6% 6,936 4 0 18 0 0 0 0 17 39 אבו סנאן ABU SINAN 0.0% 12,311 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 4 4 אבו רוקייק ABU RUQAYYEQ 0.0% 8,597 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 )שבט( אבטליון AVTALYON 1.8% 329 2 0 2 0 0 0 0 2 6 אביאל AVI'EL 2.2% 723 9 3 2 0 0 0 0 2 16 אביבים AVIVIM 0.6% 485 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 3 3 אביגדור AVIGEDOR 1.4% 801 1 0 3 0 0 0 0 7 11 אביחיל AVIHAYIL 3.7% 1,372 14 1 5 5 0 0 0 26 51 אביטל AVITAL 1.1% 548 4 0 0 0 0 1 0 2 6 אביעזר AVI'EZER 11.0% 682 6 0 13 0 1 2 0 55 75 אבירים ABBIRIM 1.9% 210 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 3 4 אבן יהודה EVEN YEHUDA 2.6% 12,327 102 14 49 11 14 17 4 133 323 אבן מנחם EVEN MENAHEM 1.2% 338 0 0 3 0 0 0 0 1 4 אבן ספיר EVEN SAPPIR 4.6% 656 6 0 5 3 0 2 0 16 30 אבן שמואל EVEN SHEMU'EL 1.1% 708 4 0 2 2 0 0 0 0 8 אבני איתן AVNE ETAN 2.7% 594 3 0 11 2 0 0 0 0 16 אבני חפץ AVNE HEFEZ 5.8% 1,597 55 0 2 24 1 2 0 11 93 אבנת AVENAT