National Geographic Magazine - NGM.Com

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Graham Budd Auctions Sotheby's 34-35 New Bond Street Sporting Memorabilia London W1A 2AA United Kingdom Started 22 May 2014 10:00 BST

Graham Budd Auctions Sotheby's 34-35 New Bond Street Sporting Memorabilia London W1A 2AA United Kingdom Started 22 May 2014 10:00 BST Lot Description An 1896 Athens Olympic Games participation medal, in bronze, designed by N Lytras, struck by Honto-Poulus, the obverse with Nike 1 seated holding a laurel wreath over a phoenix emerging from the flames, the Acropolis beyond, the reverse with a Greek inscription within a wreath A Greek memorial medal to Charilaos Trikoupis dated 1896,in silver with portrait to obverse, with medal ribbonCharilaos Trikoupis was a 2 member of the Greek Government and prominent in a group of politicians who were resoundingly opposed to the revival of the Olympic Games in 1896. Instead of an a ...[more] 3 Spyridis (G.) La Panorama Illustre des Jeux Olympiques 1896,French language, published in Paris & Athens, paper wrappers, rare A rare gilt-bronze version of the 1900 Paris Olympic Games plaquette struck in conjunction with the Paris 1900 Exposition 4 Universelle,the obverse with a triumphant classical athlete, the reverse inscribed EDUCATION PHYSIQUE, OFFERT PAR LE MINISTRE, in original velvet lined red case, with identical ...[more] A 1904 St Louis Olympic Games athlete's participation medal,without any traces of loop at top edge, as presented to the athletes, by 5 Dieges & Clust, New York, the obverse with a naked athlete, the reverse with an eleven line legend, and the shields of St Louis, France & USA on a background of ivy l ...[more] A complete set of four participation medals for the 1908 London Olympic -

Sample Download

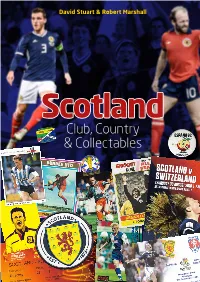

David Stuart & RobertScotland: Club, Marshall Country & Collectables Club, Country & Collectables 1 Scotland Club, Country & Collectables David Stuart & Robert Marshall Pitch Publishing Ltd A2 Yeoman Gate Yeoman Way Durrington BN13 3QZ Email: [email protected] Web: www.pitchpublishing.co.uk First published by Pitch Publishing 2019 Text © 2019 Robert Marshall and David Stuart Robert Marshall and David Stuart have asserted their rights in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the authors of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher and the copyright owners, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the terms stated here should be sent to the publishers at the UK address printed on this page. The publisher makes no representation, express or implied, with regard to the accuracy of the information contained in this book and cannot accept any legal responsibility for any errors or omissions that may be made. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 13-digit ISBN: 9781785315419 Design and typesetting by Olner Pro Sport Media. Printed in India by Replika Press Scotland: Club, Country & Collectables INTRODUCTION Just when you thought it was safe again to and Don Hutchison, the match go back inside a quality bookshop, along badges (stinking or otherwise), comes another offbeat soccer hardback (or the Caribbean postage stamps football annual for grown-ups) from David ‘deifying’ Scotland World Cup Stuart and Robert Marshall, Scottish football squads and the replica strips which writing’s answer to Ernest Hemingway and just defy belief! There’s no limit Mary Shelley. -

European Qualifiers to the 2018 FIFA World Cup Can Be Manipulated

Munich Personal RePEc Archive European qualifiers to the 2018 FIFA World Cup can be manipulated Csató, László Institute for Computer Science and Control, Hungarian Academy of Sciences (MTA SZTAKI), Laboratory on Engineering and Management Intelligence, Research Group of Operations Research and Decision Systems, Corvinus University of Budapest (BCE), Department of Operations Research and Actuarial Sciences 22 December 2017 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/83437/ MPRA Paper No. 83437, posted 23 Dec 2017 05:56 UTC European qualifiers to the 2018 FIFA World Cup can be manipulated L´aszl´oCsat´o* Institute for Computer Science and Control, Hungarian Academy of Sciences (MTA SZTAKI) Laboratory on Engineering and Management Intelligence, Research Group of Operations Research and Decision Systems Corvinus University of Budapest (BCE) Department of Operations Research and Actuarial Sciences Budapest, Hungary December 22, 2017 Ein Fehler in der ursprunglichen¨ Versammlung der Heere ist im ganzen Verlauf des Feldzuges kaum wieder gut zu machen. (Helmuth Karl Bernhard von Moltke: Taktisch-strategische Aufs¨atzeaus den Jahren 1857 bis 1871 ) Abstract Tournament organizers supposedly design rules such that a team cannot be better off by exerting a lower effort. It is shown that the European qualifiers to the 2018 FIFA World Cup are not strategy-proof in this sense: a team might be eliminated if it wins its last match in the group stage, while it advances to play-offs by playing a draw, provided that all other results remain the same. The scenario could have happened in October 2017, after four-fifth of all matches have already been played. We present a theoretical model and identify nine incentive incompatible qualifiers to recent UEFA European Championships and FIFA World Cups. -

The World Cup— a Pictorial History on Stamps by John F

Historic Events: The World Cup— A pictorial history on stamps by John F. Dunn With the World Cup beginning on June 12 and running through the championship game on July 13 in Brazil, we present here stamps that trace the history of this worldwide event from the first, 1930, competition to date. Prelude: The world’s most popular sport, football—known in the United States as soccer—has elements that trace back to ancient Greece and Rome, but the rules of the sport as we know it today came into fruition in the mid-19th Century in England, where various forms of the game were played as far back as the eight century. The first formal “International” competition was held in 1872, albeit it between England and Scotland. By 1900 the sport was sufficiently widespread that it was introduced as a demonstration sport (with no medals awarded), and then as a medal sport in the 1908 London Olympics. It was not until the 1920 Olympics that a non-Euro- pean nation competed—Egypt, along with 13 European teams—in a competition that was won by Belgium. Uru- guay won the 1924 and 1928 Olympics. By 1930, under the leadership of its President, Jules Rimet, the Federation Interna- tionale de Football Associations (FIFA) was ready to stage its own tournaments, free of the amateur restrictions of the Olympics. Hav- ing won the previous two Olympic Championships, and with the Jules Rimet and the first South American nation celebrates trophy, named “The God- its 100th Anniversary of inde- dess of Victory,” which pendence, Uruguay became the later came to be known as natural choice as the first World the Rimet Cup, on a stamp from Hungary. -

1 Introduction 2 Football, 'Race' and the Forging of British Identity

Notes 1 Introduction 1. For an opposing view of the changing composition of crowds, see Malcolm, Jones and Waddington (2000). 2. The interviews were either semi-structured or unstructured and conducted by one or both of the authors. Some survey work, of fanzine editors and of football club safety officers undertaken in the period 1995–96 also informs this work. The authors would like to acknowledge with thanks the work of Mark Carver, who participated in the formative part of this research. 3. From an interview conducted for this book, May 1998. 4. Excerpt from an interview conducted for this volume, January 1998. 5. Interview undertaken for this book, November 1997. 6. From an interview for this work, August 1997. 7. Conservative leader William Hague, in a speech to the Centre for Policy Studies in 1999 spoke of an ‘emerging English consciousness’ that was a ‘ticking time bomb’ under the constitution of the United Kingdom. Interestingly, he viewed the manifestation of the widespread painting of the St George Cross on the faces of England football supporters as evidence of this new nationalism (Shrimsley, 1999). 2 Football, ‘Race’ and the Forging of British Identity 8. Collins, who had the ‘affectionate’ nickname of ‘Darkie’, took Rochdale to the League Cup Final in 1962, losing 4–0 on aggregate to Norwich City. 9. Interview with Jeff Simons, November 1997. 10. Interview with Brendon Batson, February 1998. 11. Interview with Cyrille Regis, February 1998. 12. Ibid. 13. The Guardian, 26 January 1979. 14. Dave Bennett of Manchester City and Garth Crooks and Chris Houghton of Tottenham. -

The Transformation of Elite-Level Association Football in England, 1970 to the Present

1 The Transformation of Elite-Level Association Football in England, 1970 to the present Mark Sampson PhD Thesis Queen Mary University of London 2 Statement of Originality I, Mark Sampson, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also ackn owledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: M. Sampson Date: 30 June 2016 3 Abstract The purpose of this thesis is to provide the first academic account and analysis of the vast changes that took place in English professional football at the top level from 1970 to the present day. It examines the factors that drove those changes both within football and more broadly in English society during this period. The primary sources utilised for this study include newspapers, reports from government inquiries, football fan magazines, memoirs, and oral histories, inter alia. -

SOCCERNOMICS NEW YORK TIMES Bestseller International Bestseller

4color process, CMYK matte lamination + spot gloss (p.2) + emboss (p.3) SPORTS/SOCCER SOCCERNOMICS NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER INTERNATIONAL BESTSELLER “As an avid fan of the game and a fi rm believer in the power that such objective namEd onE oF thE “bEst booKs oF thE yEar” BY GUARDIAN, SLATE, analysis can bring to sports, I was captivated by this book. Soccernomics is an FINANCIAL TIMES, INDEPENDENT (UK), AND BLOOMBERG NEWS absolute must-read.” —BillY BEANE, General Manager of the Oakland A’s SOCCERNOMICS pioneers a new way of looking at soccer through meticulous, empirical analysis and incisive, witty commentary. The San Francisco Chronicle describes it as “the most intelligent book ever written about soccer.” This World Cup edition features new material, including a provocative examination of how soccer SOCCERNOMICS clubs might actually start making profi ts, why that’s undesirable, and how soccer’s never had it so good. WHY ENGLAND LOSES, WHY SPAIN, GERMANY, “read this book.” —New York Times AND BRAZIL WIN, AND WHY THE US, JAPAN, aUstralia– AND EVEN IRAQ–ARE DESTINED “gripping and essential.” —Slate “ Quite magnificent. A sort of Freakonomics TO BECOME THE kings of the world’s for soccer.” —JONATHAN WILSON, Guardian MOST POPULAR SPORT STEFAN SZYMANSKI STEFAN SIMON KUPER SIMON kupER is one of the world’s leading writers on soccer. The winner of the William Hill Prize for sports book of the year in Britain, Kuper writes a weekly column for the Financial Times. He lives in Paris, France. StEfaN SzyMaNSkI is the Stephen J. Galetti Collegiate Professor of Sport Management at the University of Michigan’s School of Kinesiology. -

Pga Tour Book 1991

PGA TOUR BOOK 1991 Official Media Guide of the PGA TOUR nat l t rr' ~,Inllr, CJLF uHF PLAYLIi5 C I I - : PA)L SI IIP, I )L JHNlA.rv':L.N] I l l AY ERS CHAMPIONSHIP, TOURNAMENT PLAYERS CLUB, TPC, TPC INTERNATIONAL, WORLD SERIES OF GOLF, FAMILY GOLF CENTER, TOUR CADDY, and SUPER SENIORS are trade- marks of the PGA TOUR. PGA TOUR Deane R. Beman, Commissioner Sawgrass Ponte Vedra, Fla. 32082 Telephone: 904-285-3700 Copyright@ 1990 by the PGA TOUR, Inc. All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced — electronically, mechanically or by any other means, including photocopy- ing — without the written permission of the PGA TOUR. The 1990 TOUR BOOK was produced by PGA TOUR Creative Services. Al] text inside the PGA TOUR Book is printed on ® recycled paper. OFFICIAL PGA TOUR BOOK 1991 1991 TOURNAMENT SCHEDULE CURRENT PLAYER BIOGRAPHIES 1990 TOURNAMENT RESULTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1991 PGA TOUR Tournament Schedule .....................................................4 Tournament Policy Board ..........................................................................11 Investments Board .....................................................................................12 Commissioner Deane R. Beman ...............................................................13 PGA TOUR Executive Department ............................................................14 Tournament Administration .......................................................................15 TournamentStaff ........................................................................................16 -

Televized Sport, Soap Opera and Male and Female Pleasures BARBARA O'connor School of Communications, Dublin City University, Dublin 9, Ireland

Dallas with balls: televized sport, soap opera and male and female pleasures BARBARA O'CONNOR School of Communications, Dublin City University, Dublin 9, Ireland RAYMOND BOYLE Communication Department, Glasgow Caledonian University, 70 Concaddens Road, Glasgow G4 0BA, Scotland, UK Two of the most popular of television genres, soap opera and sports coverage have been very much differentiated along gender lines in terms of their audiences. Soap opera has been regarded very much as a 'gynocentric' genre with a large female viewing audience while the audiences for television sport have been predominantly male. Gender differentiation between the genres has had implications for the popular image of each. Soap opera has been perceived as inferior; as mere fantasy and escapism for women while television sports has been perceived as a legitimate, even edifying experience for men. In this article the authors challenge the view that soap opera and television sport are radically different and argue that they are, in fact, very similar in a number of significant ways. They suggest that both genres invoke similar structures of feeling and sensibility in their respective audiences and that television sport is a 'male soap opera'. They consider the ways in which the viewing context of each genre is related to domestic life and leisure, the ways in which the textual structure and conventions of each genre invoke emotional identification, and finally, the ways in which both genres re-affirm gender identities. 'Explain the success of snooker on television? "Simple, it's Dallas with balls.' Barry Hearn, sports entrepreneur, interview with Raymond Boyle, April 1987. -

I GOOOOOOOOOOOOOOAL!! a GEOGRAPHY of the WORLD CUP: HOW the FIFA WORLD CUP IS the CATALYST for the GROWTH of SOCCER WORLDWIDE

GOOOOOOOOOOOOOOAL!! A GEOGRAPHY OF THE WORLD CUP: HOW THE FIFA WORLD CUP IS THE CATALYST FOR THE GROWTH OF SOCCER WORLDWIDE By KYLE ANDREW SPRINGER Bachelor of Arts Drury University Springfield, Missouri 2008 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE December, 2010 i GOOOOOOOOOOOOOOAL!! A GEOGRAPHY OF THE WORLD CUP: HOW THE FIFA WORLD CUP IS THE CATALYST FOR THE GROWTH OF SOCCER WORLDWIDE Thesis Approved: Dr. John Rooney, Thesis Advisor Dr. Thomas A. Wikle, Committee Member Dr. Stephen Miller, Committee Member Dr. Mark E. Payton Dean of the Graduate College ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are several people I would like to thank who have helped me throughout the process of completing my thesis. Without their help, this thesis would not have been possible. They have helped me all along the way. I would first like to thank my advisor, Dr. John Rooney for his ongoing guidance and encouragement from the beginning of the project. His knowledge and experience has greatly enhanced the finished product of this thesis. I would also like to thank Dr. Tom Wikle for his continued support and encouragement throughout the duration of the thesis. I would like to thank Dr. Stephen Miller as his input was greatly appreciated. I couldn’t have done this thesis without the continued support and encouragement of my parents, Bob and Lisa Springer. Even though there were times that become very stressful, they always helped me stay on track. I would especially like to thank my dad, because without his help, there would be no way the maps and figures would look as good as they do. -

Televized Sport, Soap Opera and Male and Female Pleasures BARBARA O'connor School of Communications, Dublin City University, Dublin 9, Ireland

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DCU Online Research Access Service Dallas with balls: televized sport, soap opera and male and female pleasures BARBARA O'CONNOR School of Communications, Dublin City University, Dublin 9, Ireland RAYMOND BOYLE Communication Department, Glasgow Caledonian University, 70 Concaddens Road, Glasgow G4 0BA, Scotland, UK Two of the most popular of television genres, soap opera and sports coverage have been very much differentiated along gender lines in terms of their audiences. Soap opera has been regarded very much as a 'gynocentric' genre with a large female viewing audience while the audiences for television sport have been predominantly male. Gender differentiation between the genres has had implications for the popular image of each. Soap opera has been perceived as inferior; as mere fantasy and escapism for women while television sports has been perceived as a legitimate, even edifying experience for men. In this article the authors challenge the view that soap opera and television sport are radically different and argue that they are, in fact, very similar in a number of significant ways. They suggest that both genres invoke similar structures of feeling and sensibility in their respective audiences and that television sport is a 'male soap opera'. They consider the ways in which the viewing context of each genre is related to domestic life and leisure, the ways in which the textual structure and conventions of each genre invoke emotional identification, and finally, the ways in which both genres re-affirm gender identities. 'Explain the success of snooker on television? "Simple, it's Dallas with balls.' Barry Hearn, sports entrepreneur, interview with Raymond Boyle, April 1987. -

Understanding Sport a Socio-Cultural Analysis

UNDERSTANDING SPORT A SOCIO-CULTURAL ANALYSIS SECOND EDITION JOHN HORNE, ALAN TOMLINSON, GARRY WHANNEL AND KATH WOODWARD UNDERSTANDING SPORT In the decade or more since publication of the first edition of Understanding Sport, both sport and wider global society have undergone profound change. In this fully updated, revised and expanded edition of their classic textbook, John Horne, Alan Tomlinson, Garry Whannel and Kath Woodward offer a critical and reflective introduction to the relationship between sport and contemporary society and explain how sport remains an important agent and symptom of socio-cultural change. Fully integrating historical, sociological, political and cultural analysis, the book covers every key topic in the study of sport and society, including: I debate, interpretation and theory I sport and the media I sport and the body I sport and politics I commercialisation I globalisation. Retaining the accessibility and scholarly rigour for which Understanding Sport has always been renowned, this new edition includes entirely new chapters on global transformations, sports mega-events and sites, and sporting bodies and governance, as well as a brief commentary on researching sport. With review and seminar questions included in every chapter, plus concise, helpful guides to further reading, Understanding Sport remains an essential textbook for all courses on sport and society, the sociology of sport, sport and social theory, or social issues in sport. John Horne is Professor of Sport and Sociology in the School of Sport, Tourism and the Outdoors at the University of Central Lancashire, where he is Director of the International Research Institute for Sport Studies (IRiSS). Alan Tomlinson is Professor of Leisure Studies and Director of Research and Development (Social Sciences) at the University of Brighton, and has authored and edited numerous volumes and more than 100 chapters/articles on sport, leisure and popular culture.