Hi Birdos4eric, April Started As Expected—Slowly. I Was in Berkeley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring in South Texas

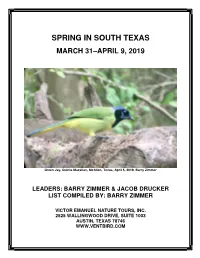

SPRING IN SOUTH TEXAS MARCH 31–APRIL 9, 2019 Green Jay, Quinta Mazatlan, McAllen, Texas, April 5, 2019, Barry Zimmer LEADERS: BARRY ZIMMER & JACOB DRUCKER LIST COMPILED BY: BARRY ZIMMER VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM SPRING IN SOUTH TEXAS MARCH 31–APRIL 9, 2019 By Barry Zimmer Once again, our Spring in South Texas tour had it all—virtually every South Texas specialty, wintering Whooping Cranes, plentiful migrants (both passerine and non- passerine), and rarities on several fronts. Our tour began with a brief outing to Tule Lake in north Corpus Christi prior to our first dinner. Almost immediately, we were met with a dozen or so Scissor-tailed Flycatchers lining a fence en route—what a welcoming party! Roseate Spoonbill, Crested Caracara, a very cooperative Long-billed Thrasher, and a group of close Cave Swallows rounded out the highlights. Strong north winds and unsettled weather throughout that day led us to believe that we might be in for big things ahead. The following day was indeed eventful. Although we had no big fallout in terms of numbers of individuals, the variety was excellent. Scouring migrant traps, bays, estuaries, coastal dunes, and other habitats, we tallied an astounding 133 species for the day. A dozen species of warblers included a stunningly yellow male Prothonotary, a very rare Prairie that foraged literally at our feet, two Yellow-throateds at arm’s-length, four Hooded Warblers, and 15 Northern Parulas among others. Tired of fighting headwinds, these birds barely acknowledged our presence, allowing unsurpassed studies. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 74/Thursday, April 16, 2020/Rules

21282 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 74 / Thursday, April 16, 2020 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR United States and the Government of United States or U.S. territories as a Canada Amending the 1916 Convention result of recent taxonomic changes; Fish and Wildlife Service between the United Kingdom and the (8) Change the common (English) United States of America for the names of 43 species to conform to 50 CFR Part 10 Protection of Migratory Birds, Sen. accepted use; and (9) Change the scientific names of 135 [Docket No. FWS–HQ–MB–2018–0047; Treaty Doc. 104–28 (December 14, FXMB 12320900000//201//FF09M29000] 1995); species to conform to accepted use. (2) Mexico: Convention between the The List of Migratory Birds (50 CFR RIN 1018–BC67 United States and Mexico for the 10.13) was last revised on November 1, Protection of Migratory Birds and Game 2013 (78 FR 65844). The amendments in General Provisions; Revised List of this rule were necessitated by nine Migratory Birds Mammals, February 7, 1936, 50 Stat. 1311 (T.S. No. 912), as amended by published supplements to the 7th (1998) AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, Protocol with Mexico amending edition of the American Ornithologists’ Interior. Convention for Protection of Migratory Union (AOU, now recognized as the American Ornithological Society (AOS)) ACTION: Final rule. Birds and Game Mammals, Sen. Treaty Doc. 105–26 (May 5, 1997); Check-list of North American Birds (AOU 2011, AOU 2012, AOU 2013, SUMMARY: We, the U.S. Fish and (3) Japan: Convention between the AOU 2014, AOU 2015, AOU 2016, AOS Wildlife Service (Service), revise the Government of the United States of 2017, AOS 2018, and AOS 2019) and List of Migratory Birds protected by the America and the Government of Japan the 2017 publication of the Clements Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA) by for the Protection of Migratory Birds and Checklist of Birds of the World both adding and removing species. -

ZSL National Red List of Nepal's Birds Volume 5

The Status of Nepal's Birds: The National Red List Series Volume 5 Published by: The Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London, NW1 4RY, UK Copyright: ©Zoological Society of London and Contributors 2016. All Rights reserved. The use and reproduction of any part of this publication is welcomed for non-commercial purposes only, provided that the source is acknowledged. ISBN: 978-0-900881-75-6 Citation: Inskipp C., Baral H. S., Phuyal S., Bhatt T. R., Khatiwada M., Inskipp, T, Khatiwada A., Gurung S., Singh P. B., Murray L., Poudyal L. and Amin R. (2016) The status of Nepal's Birds: The national red list series. Zoological Society of London, UK. Keywords: Nepal, biodiversity, threatened species, conservation, birds, Red List. Front Cover Back Cover Otus bakkamoena Aceros nipalensis A pair of Collared Scops Owls; owls are A pair of Rufous-necked Hornbills; species highly threatened especially by persecution Hodgson first described for science Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson and sadly now extinct in Nepal. Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of participating organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of any participating organizations. Notes on front and back cover design: The watercolours reproduced on the covers and within this book are taken from the notebooks of Brian Houghton Hodgson (1800-1894). -

Mycerobas Affinis)

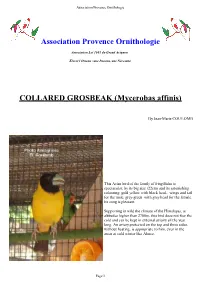

Association Provence Ornithologie Association Provence Ornithologie Association Loi 1901 du Grand Avignon Élever l’Oiseau : une Passion, une Nécessité. COLLARED GROSBEAK (Mycerobas affinis) By Jean-Marie COULOMB This Asian bird of the family of fringillidae is spectacular, by its big size (22cm) and its astonishing colouring: gold yellow with black head, wings and tail for the male, grey-green with gray head for the female. Its song is pleasant. Supporting in wild the climate of the Himalayas, at altitudes higher than 2700m, this bird does not fear the cold and can be kept in external aviairy all the year long. An aviary protected on the top and three sides, without heating, is appropriate to him, even in the areas at cold winter like Alsace. Page 1 Association Provence Ornithologie In nature, it eats seeds (including those of conifers), of buds, fruits and insects. In captivity, its basic mode can be consisted a mixture of seeds for large parakeets, adapted to the power of its imposing beak. It accepts, of course, other food and benefits from the variety offered: various seeds, seeds to germinate for parrot, fruits (apples, fresh grape, soaked dry grapes, pear, black elder tree, tomato, melon, cucumber.), insects, insectivorous softfood. For the reproduction, it is preferable to isolate each couple in a separate aviary. An Alsatian breeder of my knowledge reports that with the birth of the youngs, this bird becomes almost exclusively insectivorous. After 4 days, the parents start to bring more varied food. The reproduction in captivity is not current, but it was already succeeded by some European breeders. -

Faunal Diversity of Kitchen Gardens of Sikkim

Eco. Env. & Cons. 26 (November Suppl. Issue) : 2020; pp. (S29-S35) Copyright@ EM International ISSN 0971–765X Faunal diversity of Kitchen Gardens of Sikkim Aranya Jha, Sangeeta Jha and Ajeya Jha SMIT (Sikkim Manipal University), Tadong 737 132, Sikkim, India (Received 20 March, 2020; Accepted 20 April, 2020) ABSTRACT What is the faunal richnessof rural kitchen gardensof Sikkim? This was the research question investigated in this study. Kitchen gardens have recently been recognized as important entities for biodiversity conservations. This recognition needs to be backed by surveys in various regions of the world. Sikkim, a Himalayan state of India, in this respect, is important, primarily because it is one of the top 10 biodiversity hot-spots globally. Also because ecologically it is a fragile region. Methodology is based on a survey of 67 kitchen gardens in Sikkim and collecting relevant data. The study concludes that in all 80 (tropical), 74 (temperate) and 17 (sub-alpine) avian species have been reported from the kitchen gardens of Sikkim. For mammals these numbers are 20 (tropical) and 9 (temperate). These numbers are indicative and not exhaustive. Key words : Himalayas, Rural kitchen gardens, Tropical, Temperate, Sub-alpine, Aves, Mammals. Introduction Acharya, (2010). Kitchen gardens and their ecological benefits: Re- Kitchen gardens have been known to carry im- cently ecological issues have emerged as highly sig- mense ecological significance. When we, as a civili- nificant and naturally ecologically important facets zation, witness the ecological crisis that we have such as agricultural lands, mountains, forests, rivers ourselves created we find a collective yearning for and oceans have been identified as critical entities. -

Count in a Decade. Eastern Screech-Owls Had Their Second Best Count in 20 Years—Kudos to Rathbun for Locating 19

count in a decade. Eastern Screech-Owls had their second best count in 20 years—kudos to Rathbun for locating 19. Northern Saw-whet Owls had their best year ever. Belted Kingfishers had their best count in five seasons. After an excep- tional count last year, Red-headed Woodpecker numbers fell well below their 10-year average. Pileated Woodpeckers set a new high. Northern Shrikes were at near record numbers. Probably due to a lack of snow cover, Horned Larks were hard to find. Red- Long-tailed Duck (Clangula hyemalis) female, Kansas City, Missouri. Photo/Mike Stoakes breasted Nuthatches were uncommon also. Brown Creepers and Winter Wrens A Black-legged Kittiwake at Maryville There were no reports of Greater Prairie- were in very good numbers. Ruby- and a Common Ground-Dove at Chicken, Northern Goshawk, Greater crowned Kinglets were on four counts. Weldon Spring represent first Missouri Roadrunner, or Snow Bunting. Bald It was an average year for thrushes. CBC records. Several other species were Eagles (878) and Eastern Bluebirds (2533) Mockingbirds were at Green Island and only observed on only one count: Long- were seen on all 24 counts. Winter erratic Burlington. Brown Thrashers were at tailed Duck (2, Kansas City), Eared passerines occurred in low numbers. The Dallas County and Burlington. No cat- Grebe (1, Horton-Four Rivers), Black- only report of Red-breasted Nuthatch birds were found. crowned Night-Heron (1, Columbia), was five at Knob Noster. A total of 910 Spotted Towhees were at Sioux City, Prairie Falcon (1, Horton-Four Rivers), Lapland Longspurs were reported from DeSoto N.W.R., and Shenandoah. -

2016 GBBC Summary

2016 GBBC Summary Each year we wonder if the bird watchers of the world can possibly top their past performances in the Great Backyard Bird Count. And each year we’re amazed! The 2016 GBBC was epic. An estimated 163,763 bird watchers from more than 130 countries joined in. Participants submitted 162,052 bird checklists reporting 5,689 species--more than half the known bird species in the world and 599 more species than last year! This was the 19th year for the event which is a joint project of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and the National Audubon Society with partner Bird Studies Canada. The information gathered by tens of thousands of volunteers helps track the health of bird populations on a global scale using the eBird online checklist program. Before we hit some of the highlights of this year’s count, let’s crunch a few more numbers for our popular Top 10 lists. Note that some of the numbers may still change very slightly if checklists for the GBBC dates are added through eBird. Top 10 most frequently reported species: (number of GBBC checklists reporting this species) Dark-eyed Junco by Vicki Miller, California, 2016 GBBC. Species Number of Checklists Dark-eyed Junco 63,110 Northern Cardinal 62,323 Mourning Dove 49,630 Downy Woodpecker 47,393 Blue Jay 45,383 American Goldfinch 43,204 House Finch 41,667 Tufted Titmouse 38,130 Black-capped Chickadee 37,923 American Crow 37,277 Data totals as of March 2, 2016 Note: All Top 10 species are North American, reflecting high participation from this region. -

The Ornithological Importance of Thrumshingla National Park, Bhutan

FORKTAIL 16 (2000): 147-162 The ornithological importance of Thrumshingla National Park, Bhutan CAROL INSKIPP, TIM INSKIPP and SHERUB Thrumshingla National Park is one of four national parks in Bhutan and was gazetted in 1998 to ensure the conservation of biodiversity in the central belt of the country. Two bird surveys have been carried out in the park: in April and May 1998 and in January 2000. Based on these surveys and records from other sources, a list of 345 bird species has been compiled for the park up to the end of May 2000. This includes three globally threatened species, 15 of Bhutan’s near-threatened species and eight of the country’s 11 restricted range species. Warm broadleaved forest was found to be the most valuable for bird species in both the breeding season and in winter, followed by cool broadleaved forest. Fir and hemlock, especially those with an understorey of rhododendron and bamboo, were the richest forests for birds at higher altitudes. INTRODUCTION highway runs through approximately the middle of the park from Bumthang, via Ura, Sengor, Namling, Bhutan lies in the eastern Himalayas, one of the world’s Yongkhala to Lingmethang. The park’s altitudinal range biodiversity ‘hotspots’ and identified as an Endemic Bird extends from 1,400 m below Saleng in the core area Area by BirdLife International (Stattersfield et al. 1998). and 700 m at Lingmethang in the buffer zone to over The country has an extensive protected area system, 6,000 m at Thrumshingla Peak. encompassing 26% of its land area and covering the Like most of Bhutan, Thrumshingla National Park full range of the nation’s major ecosystem types. -

Birds of the South Texas Brushlands

TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE BIRDS of the BY JOHN C. ARVIN SOUTH TEXAS BRUSHLANDS A Field Checklist June 2007 TPWD receives federal assistance from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and other federal agencies. TPWD is therefore subject to Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, in addition to state anti-discrimination laws. TPWD will comply with state and federal laws prohibiting discrimination based on race, color, national origin, age, sex or disability. If you believe that you have been discriminated against in any TPWD program, activity or event, you may contact the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Division of Federal Assistance, 4401 N. Fairfax Drive, Mail Stop: MBSP-4020, Arlington, VA 22203, Attention: Civil Rights Coordinator for Public Access. Birds of the South Texas Brushlands: A Field Checklist Second Edition INTRODUCTION he South Texas Brushlands ecoregion, also known as the Rio Grande Plain or Tamaulipan Brushlands, consists of the southern one fifth or so of the state, south of the Edwards TPlateau and west of the San Antonio River. It includes the Rio Grande Valley from about Del Rio to where the river empties into the Gulf of Mexico and the lower coast of Texas from Baffin Bay southward. This region is flat to gently rolling with a few higher hills and cliffs along the Rio Grande. This vast plain is covered mostly with a dense growth of low thorny trees, shrubs and cacti. -

Askot Landscape, Uttarakhand Phase

Evaluation of Birds as Potential Indicator Species for Long Term Monitoring: Askot Landscape, Uttarakhand Phase – 1 Report BCRLIP Coordinator Sh. V. K. Uniyal Bird Component Investigator Sh. R. Suresh Kumar Project Assistant Ankita Bhattacharya Ministry of Environment, Forests & Climate Change Uttarakhand Forest Department World Bank Wildlife Instituute of India January, 2015 Further Contact: BCRLIP Coordinator Sh. V. K. Uniyal Department of Protected Area Network, WL Management and Conservation Education Wildlife Institute of India, Chandrabani Dehradun, India 248 001 Tell: 00 91 135 2646207 Fax: 00 91 135 2640117 E-mail; [email protected] Bird Component Investigator Sh. R Suresh Kumar Department of Endangered Species Management Wildlife Institute of India, Chandrabani Dehradun, India 248 001 Tell: 00 91 135 2646161 Fax: 00 91 135 2640117 E-mail; [email protected] Photo Credits: Front and Back Cover Photographs: Pankaj Kumar, Ankita Bhattacharya, Soni Bisht and Suresh Kumar Rana Main report Photographs: Suresh Kumar Rana and World Pheasant Asssociation (WPA) Citation: Bhattacharya, A., Kumar, R. S. and Uniyal, V. K. (2015): Evaluation of Birds as Potential Indicator Species for Long Term Monitoring: Askot landscape, Uttarakhand, Phase 1 – Report, Wildlife Institute of India. Pp 29. Contents List of Tables ii List of Figures iii Acknowledgements iv 1 Background 1 2 Study area 2 3 Methods 4 4 Findings of the study 6 5 Future Plans 24 6 References 24 Annexure I: Checklist of birds of Askot Landscape with 25 reports of birds seen during this study List of Tables Table No. Table Name Page No. 1 a. List of villages surveyed along Gori river basin in Askot 6 Landscape 1 b. -

Learn About Texas Birds Activity Book

Learn about . A Learning and Activity Book Color your own guide to the birds that wing their way across the plains, hills, forests, deserts and mountains of Texas. Text Mark W. Lockwood Conservation Biologist, Natural Resource Program Editorial Direction Georg Zappler Art Director Elena T. Ivy Educational Consultants Juliann Pool Beverly Morrell © 1997 Texas Parks and Wildlife 4200 Smith School Road Austin, Texas 78744 PWD BK P4000-038 10/97 All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means – graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or information storage and retrieval systems – without written permission of the publisher. Another "Learn about Texas" publication from TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE PRESS ISBN- 1-885696-17-5 Key to the Cover 4 8 1 2 5 9 3 6 7 14 16 10 13 20 19 15 11 12 17 18 19 21 24 23 20 22 26 28 31 25 29 27 30 ©TPWPress 1997 1 Great Kiskadee 16 Blue Jay 2 Carolina Wren 17 Pyrrhuloxia 3 Carolina Chickadee 18 Pyrrhuloxia 4 Altamira Oriole 19 Northern Cardinal 5 Black-capped Vireo 20 Ovenbird 6 Black-capped Vireo 21 Brown Thrasher 7Tufted Titmouse 22 Belted Kingfisher 8 Painted Bunting 23 Belted Kingfisher 9 Indigo Bunting 24 Scissor-tailed Flycatcher 10 Green Jay 25 Wood Thrush 11 Green Kingfisher 26 Ruddy Turnstone 12 Green Kingfisher 27 Long-billed Thrasher 13 Vermillion Flycatcher 28 Killdeer 14 Vermillion Flycatcher 29 Olive Sparrow 15 Blue Jay 30 Olive Sparrow 31 Great Horned Owl =female =male Texas Birds More kinds of birds have been found in Texas than any other state in the United States: just over 600 species. -

Important Bird Areas (Iba)

1 IMPORTANT BIRD AREAS (IBA) PROGRAMME SUB THEMATIC REWIEW NOTE FOR THE NATIONAL BIODIVERSITY STRATEGY AND ACTION PLAN Supriya Jhunjhunwala IBA Ornithology Officer Bombay Natural History Society Hornbill House, Shaheed Bhagat Singh Road Mumbai 400023 1. Introduction Important Bird Areas and Biodiversity Conservation India ranks amongst the most biodiverse countries in the world. Currently 1220 species of breeding, staging and wintering birds, occupying a wide array of natural, semi natural and urban habitats are known from India (Manakadan & Pittie 2001). Notwithstanding the deep rooted traditional conservation of natural resources that still exist in India, growth of human population result in agricultural intensification, expansion in industrial capacity, increased levels of wetland drainage, pollution, deforestation for fuel wood and timber, coastal land reclamation and desertification. Changes in land use patterns have had a detrimental impact on habitats, which have been fragmented and reduced in extent and diversity. This has resulted in a marked reduction in abundance and range of several bird species. Seventy-nine Indian bird species are globally threatened with extinction of these 9 are listed as Critical, 10 species as Endangered, 57 are Vulnerable, 2 are conservation dependent and 1 is data deficient. A further 52 are classified as Near Threatened (BirdLife International 2000). Large proportions of the rest of the bird species in India is rapidly declining and are in urgent need of conservation action. Approaches to biodiversity conservation The conservation of biodiversity and natural resources including birds can generally be approached in the following ways: • Protection of species from direct threats like hunting is done through legislation and direct persecution.