Dehumanization in Everyday Politics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Making Decisions from a Distance: the Impact of Technological

Making Decisions From a Distance: The Impact of Technological Mediation on Riskiness and Dehumanization Min Kyung Lee1, Nathaniel Fruchter1, Laura Dabbish1,2 1Human-Computer Interaction Institute, 2Heinz College Carnegie Mellon University {mklee, fruchter, dabbish}@cmu.edu ABSTRACT Are people risk-seeking and more dehumanizing at a Telepresence means business people can make deals in distance? Are certain people more risk seeking and other countries, doctors can give remote medical advice, dehumanizing at a distance than others? and soldiers can rescue someone from thousands of miles away. When interaction is mediated, people are removed While telepresence technologies support sharing and from and lack context about the person they are making collaboration across geographical and temporal boundaries, decisions about. In this paper, we explore the impact of decision makers are now decontextualized from their technological mediation on risk and dehumanization in decision targets. Research in social psychology and decision-making. We conducted a laboratory experiment decision science suggests that this mediation and de- involving medical treatment decisions. The results suggest contextualization could create distance in how decision that technological mediation influences decision making, makers construe, feel toward, and engage with remote but its influence depends on an individual’s self-construal: people and events [45]. This perceived distance may be participants who saw themselves as defined through their exacerbated by intrinsic differences among cultural relationships (interdependent self-construal) recommended dimensions, such as styles of self-construal [10] as previous riskier and more painful treatments in video conferencing work has shown that culture changes the nature of mediated than when face-to-face. -

Incivility, Bullying, and Workplace Violence

AMERICAN NURSES ASSOCIATION POSITION STATEMENT ON INCIVILITY, BULLYING, AND WORKPLACE VIOLENCE Effective Date: July 22, 2015 Status: New Position Statement Written By: Professional Issues Panel on Incivility, Bullying and Workplace Violence Adopted By: ANA Board of Directors I. PURPOSE This statement articulates the American Nurses Association (ANA) position with regard to individual and shared roles and responsibilities of registered nurses (RNs) and employers to create and sustain a culture of respect, which is free of incivility, bullying, and workplace violence. RNs and employers across the health care continuum, including academia, have an ethical, moral, and legal responsibility to create a healthy and safe work environment for RNs and all members of the health care team, health care consumers, families, and communities. II. STATEMENT OF ANA POSITION ANA’s Code of Ethics for Nurses with Interpretive Statements states that nurses are required to “create an ethical environment and culture of civility and kindness, treating colleagues, coworkers, employees, students, and others with dignity and respect” (ANA, 2015a, p. 4). Similarly, nurses must be afforded the same level of respect and dignity as others. Thus, the nursing profession will no longer tolerate violence of any kind from any source. All RNs and employers in all settings, including practice, academia, and research, must collaborate to create a culture of respect that is free of incivility, bullying, and workplace violence. Evidence-based best practices must be implemented to prevent and mitigate incivility, bullying, and workplace violence; to promote the health, safety, and wellness of RNs; and to ensure optimal outcomes across the health care continuum. -

SOCIAL DISTANCES of WHITES to RACIAL OR ETHNIC Minoritiesl Nina Michalikova Texas Woman

SOCIAL DISTANCES OF WHITES TO RACIAL OR ETHNIC MINORITIESl Nina Michalikova Texas Woman 's University Philip Q. Yang Texas Woman 's University Social distance has been studied by researchers since Emory Bogar dus (1925) first developed the social distance scale almost nine decades ago. Social distance refers to "the grades and degrees of understanding and intimacy which characterize pre-social and social relations gener ally" (Park 1924). As social distance increases, people tend to distance themselves from members of another racial or ethnic group or exclude them from their lives (Yancey 2003). An examination of social distances between different racial or ethnic groups in the United States can help better understand racial and ethnic relations, conflict, cooperation, and alliance. Previous research on social distance almost exclusively focuses on the social distance between blacks and whites. Results are mixed. Often based on indirect measures of social distance, many studies suggest that the social distance of whites to African Americans has decreased over time, even though ethnic prejudice has not vanished (e.g., Firebaugh and Davis 1988; Schuman et al. 1997; Steeh and Schuman 1992). Today whites are more willing to live in the same neighborhood with African Americans, to accept interracial marriage, to report having a black person as a close friend, and to vote for a black president (Alba, Rumbaut, and Marotz 2005; Healey 2004; Jaynes and Williams 2000; Ladd 2002; Yan cey 1999). Findings from existing studies indicate improvements in school and residential integration of blacks. For example, the percentage of whites who object to sending their children to schools where the ma jority of students were black decreased from 67 percent in 1958 to 34 percent in 1990; the percentage of whites who would definitely move out if blacks moved into their neighborhood in great numbers also declined from 50 percent in 1958 to 18 percent in 1990 (Schuman et al. -

Gender Equality Is Part of the Civility Issue...Continued from Page 21 Harming a Client’S Case, Or Fear of Antagonizing a Judge

ABTL - Los Angeles Summer 2019 GENDER EQUALITY Incivility can take many forms. The most common IS PART OF THE CIVILITY ISSUE category consists of disrespectful behaviors, ranging from mild discourtesy to extreme hostility. Examples include At a recent ABTL joint board condescension, interruption, profanity, and derogatory retreat, there was a session dedicated comments of a gendered nature, such as comments about an to a discussion of civility in the legal attorney’s pregnancy or appearance. profession. Toward the end of a several- Common complaints by women lawyers include being hour discussion, it was posited that interrupted inappropriately or “talked over” while speaking, any discussion of civility in the legal jokes and comments that are sexist, and comments that profession must include a discussion trivialize gender discrimination. Justice about the very different treatment Other common examples reported by women lawyers Lee Smalley Edmon that women receive compared to include being professionally discredited. The misbehavior their male colleagues. While gender includes implicit or explicit challenges to their competence, discrimination is obviously a serious being addressed unprofessionally (such as with terms of issue in society as a whole, the legal “endearment”), being critiqued on their physical appearance profession should lead in the effort to or attire, and being mistaken for nonlawyers (such as court eliminate gender bias. Rather than reporters or support staff). A judge reported, “People tell me viewing gender discrimination as an all the time I don’t look like a judge even when I’m in my robe entirely separate issue, we treat it here at official events.” An attorney recalled an incident in which, Judge Samantha P. -

Civility in the Workplace

DEPARTMENT OF HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT POLICY 2.35 CIVILITY IN THE WORKPLACE APPLICATION: All Executive Branch employees whether covered or non-covered under the Virginia Personnel Act. This includes all teaching, research and administrative faculty, employees of the Governor's Office, the Office of the Lieutenant Governor, and the Office of the Attorney General. Expectations for appropriate behaviors extend to contract workers, customers, clients, students, volunteers, and other third parties in the workplace. PURPOSE: It is the policy of the Commonwealth to foster a culture that demonstrates the principles of civility, diversity, equity, and inclusion. In keeping with this commitment, workplace harassment (including sexual harassment), bullying (including cyber-bullying), and workplace violence of any kind are prohibited in state government agencies. POLICY SUMMARY: This policy is to ensure that agencies provide a welcoming, safe, and civil workplace for their employees, customers, clients, contract workers, volunteers, and other third parties and to increase awareness of all employees' responsibility to conduct themselves in a manner that cultivates mutual respect, inclusion, and a healthy work environment. All employees should receive training from either the agency EEO Officer or the Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Unit in the Department of Human Resource Management to assist them in recognizing, preventing, and reporting behaviors that constitute harassment, sexual harassment, bullying, cyber-bullying, and threats or violence related to the workplace. Agencies are required to provide avenues for addressing complaints; to communicate how employees may access these procedures and participate in related investigations, free of retaliation; and to hold employees accountable for violations of this policy. AUTHORITY & INTERPRETATION: Title 2.2 of the Code of Virginia The Director of the Department of Human Resource Management is responsible for official interpretation of this policy, in accordance with §2.2-1201 of the Code of Virginia. -

Applying Construal Level Theory to Communication Strategies for Participatory Sustainable Development

Applying Construal Level Theory to Communication Strategies for Participatory Sustainable Development D.H. Strongheart Florence Obison Fabio Bordoni School of Engineering Blekinge Institute of Technology Karlskrona, Sweden Thesis submitted for completion of Master of Strategic Leadership towards Sustainability, Blekinge Institute of Technology, Karlskrona, Sweden. Abstract: To the vast majority of people, the terms “sustainability” and “sustainable development” are unfamiliar, and, when they are recognized, there is still a great deal of interpretability as to their significance. Since no consensus exists regarding these terms, communication efforts to promote action and awareness among citizens must invariably “frame” the issue of sustainable development in one way or another. By and large, most communication strategies promote small private-sphere actions relevant to patterns of consumption. While these small actions are helpful, participatory, collective, public-sphere activism towards sustainability is much more potent and desirable. In attempting to engage this type of participatory action, communicators must understand the psychological barriers that are likely to confront their efforts. Communication professionals recognize that one such barrier, that of perceived, or, psychological distance, from issues of non-sustainability is especially pernicious. This paper attempts to apply Construal Level Theory (CLT), which provides “an account of how psychological distance influences individuals’ thoughts and behavior” (Trope et al. 2007) to the design of communication strategies for participatory sustainable development. After providing a thorough review of CLT, the authors examine the many ways that the theory can contribute to the design of communication strategies for participatory sustainable development. Keywords: Construal Level Theory, psychological distance, high construal mindset, framing, participatory sustainable development. -

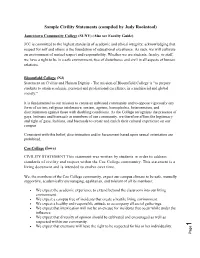

Sample Civility Statements (Compiled by Judy Rookstool)

Sample Civility Statements (compiled by Judy Rookstool) Jamestown Community College (SUNY) (Also see Faculty Guide) JCC is committed to the highest standards of academic and ethical integrity, acknowledging that respect for self and others is the foundation of educational excellence. As such, we will cultivate an environment of mutual respect and responsibility. Whether we are students, faculty, or staff, we have a right to be in a safe environment, free of disturbance and civil in all aspects of human relations. Bloomfield College (NJ) Statement on Civility and Human Dignity - The mission of Bloomfield College is "to prepare students to attain academic, personal and professional excellence in a multiracial and global society." It is fundamental to our mission to create an unbiased community and to oppose vigorously any form of racism, religious intolerance, sexism, ageism, homophobia, heterosexism, and discrimination against those with disabling conditions. As the College recognizes the presence of gays, lesbians and bisexuals as members of our community, we therefore affirm the legitimacy and right of gays, lesbians, and bisexuals to create and enrich their cultural experience on our campus. Consistent with this belief, discrimination and/or harassment based upon sexual orientation are prohibited. Coe College (Iowa) CIVILITY STATEMENT This statement was written by students in order to address standards of civility and respect within the Coe College community. This statement is a living document and is intended to evolve over time. We, the members of the Coe College community, expect our campus climate to be safe, mutually supportive, academically encouraging, egalitarian, and tolerant of all its members: We expect the academic experience to extend beyond the classroom into our living environment. -

Guidance for Physical and Social Distancing

Risk Communication and Community Engagement Guidance for Physical and Social Distancing Background Physical and social distancing measures are associated with limiting contact between people during disease outbreaks. These measures when applied are often enhanced by lockdowns or shutdowns as part of broader risk communication and community engagement strategies to halt the transmission of disease outbreaks. As the COVID-19 situation evolves, WHO has recommended the practice of physical distancing through various tools, in particular, the guidance on risk assessment for mass gatherings during COVID-19. Definitions Physical distancing refers to individual distancing and is defined as an act of keeping distance or space between one person and another especially if they are coughing, sneezing, or have a fever.1 Examples include the use of non-contact greetings, maintaining a given distance of at least one metre between individuals, staying at home, individual quarantine, etc.2 It is one of the most effective measures recommended to avoid being exposed to COVID-19 and slowing its spread locally, nationally and globally. It entails limiting close contact with others outside one’s household, indoors and in outdoor spaces. However, physical distancing may, in some settings like the African Region, have adverse effects and contribute directly and indirectly to COVID-19-related deaths. It is therefore important that while practising physical distancing, people should maintain and even increase social proximity through non-physical means, for example through social media platforms and communication technologies.2 Social distancing refers to community distancing and is a set of interventions or measures taken to prevent the spread of a contagious disease by maintaining a physical distance between people and reducing the number of times people come into close contact with one another. -

Student Rudeness & Technology

Student Rudeness & Technology: Going Beyond the Business Classroom Barbara A. Schuldt, Ph.D., CCP Professor of Marketing & Supply Chain Management Southeastern Louisiana University College of Business Hammond, Louisiana Jeff W. Totten, D.B.A., PCM Assistant Professor of Marketing McNeese State University College of Business Lake Charles, Louisiana C. Mitchell Adrian, D.B.A. Dean, College of Business McNeese State University College of Business Lake Charles, Louisiana Susie S. Cox, D.B.A. Assistant Professor of Management McNeese State University College of Business Lake Charles, Louisiana ABSTRACT This exploratory study examines how society is adapting to an invasion of per- sonal technology. Specifically, the paper reports a pretest study about incivility and the use of personal technology. Findings from this study are useful in provid- ing initial views on demographic differences concerning perceptions about inci- vility and rudeness in the workplace, religious settings and classroom settings. INTRODUCTION “Common civility is becoming a lost art. The new norm has been to expect some level of Have you been in a work, school or social setting rudeness and disrespect in just about every facet only to have the person you are having a face-to- of our lives” (Weeks 2011, p. 3). Personal tech- face conversation with stop abruptly and take a nology offers many benefits to society but also call, or read or write a text message, or even make is a factor affecting the lack of civility (Rashid a call? Current technology is being embedded 2005). We enjoy being able to chat with our clos- into every aspect of our lives. -

Employee Handbook for Staff

EMPLOYEE HANDBOOK FOR STAFF TABLE OF CONTENTS About The University ........................................................................................................ 4 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 6 WORKPLACE CONDUCT ................................................................................................. 7 Attendance (Absenteeism, Tardiness & Job Abandonment) ...............................................7 Business Conduct .................................................................................................................... 10 Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO) .................................................................................. 17 Nepotism ...................................................................................................................................18 Personal Business, Visitors, and Pets .................................................................................. 20 Smoking/Nonsmoking ............................................................................................................. 20 Social Media .............................................................................................................................. 21 Solicitations .............................................................................................................................. 23 Substance Abuse .................................................................................................................... -

Racial Distancing and Sensitivity to Stigmatization Among Future

RACIAL DISTANCING AND SENSITIVITY TO STIGMATIZATION AMONG FUTURE BLACK PROFESSIONALS by CODDY L. CARTER UTZ MCKNIGHT, COMMITTEE CHAIR STEPHEN THOMA, COMMITTEE CO-CHAIR NIRMALA EREVELLES ADRIANE SHEFFIELD SARA TOMEK A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Educational Studies in Psychology, Research Methodology, and Counseling in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2018 Copyright Coddy L. Carter 2018 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Professional occupations requiring higher education have long been paths to upward mobility for Black people in the United States. This mobility has historically been tied to both social and economic advancement. Whether advancement was subjective or objective, there was some form of distancing from the broader Black community. The three studies of the present dissertation used national and regional samples to test the problem of whether future Black professionals endorsed racial distancing behaviors. Results showed that racial distancing was composed of economic and social components. Moreover, high levels of Black social interactions and high ratings of emotional bonds to the Black community were negative determinants of the social distance defined as group distancing. High levels of emotional bonds alone were negative determinants of economic distancing. Characteristics of high racial distancing included discomfort in Black social spaces and a desire to turn one’s back on the Black community for advancement. Though racial distancing was present, approximately 73 percent of the national sample was low in economic and group distancing. In examining reasons for racial distancing, the regional sample results showed that a majority of respondents were highly sensitive to racial stigmatization whether or not they were from racially diverse communities or predominantly Black spaces. -

The Civility Discourse: Where Do We Stand and How Do We Proceed?

The Civility Discourse: Where Do We Stand and How Do We Proceed? Abdalla Aly, Casey Brent, Victoria Chihos, Ian Clark, Mazen El Ghaziri, Deborah Mansdorf, and Oksana Mishler 1 The President’s Symposium and White Paper Project is an interprofessional initiative that engages University of Maryland, Baltimore faculty, staff, and students in a yearlong conversation on a topic that is of interest and importance to the University and its community. The symposium is a joint initiative of the President’s Office and the Office of Interprofessional Student Learning & Service Initiatives. 2 “ Benjamin Franklin 3 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 5 INTRODUCTION 6 I. CIVILITY AND INCIVILITY DEFINED 7 A. What is Civility? 7 B. What is Incivility? 8 C. Working Definitions 8 II. THE STATE OF (IN)CIVILITY 10 A. Why is Incivility a Problem? 10 1. Effects of Incivility in the Workplace and Classroom 11 2. Effects of Incivility on Patients and Clients 12 3. Other Considerations Regarding Incvility 13 B. What is the Scope of the Problem at UMB? 14 1. Methods and Evidence Synthesis 14 2. Results: Themes from the Deans 15 3. Results: Campus Survey 17 III. EXISTING CIVILITY INITIATIVES 19 A. Initiatives at UMB 19 B. Civility at Other Educational Institutions 20 IV. FELLOWS’ RECOMMENDATIONS 23 1. Incorporate Civility Into Professional Schools’ Bylaws 24 2. Incorporate Civility Into Professional Schools’ Curricula 26 3. Measure and Enforce Civility Campus-Wide 28 4. Leverage Exisiting Initiatives and Resources 30 5. Appoint a Civility Commission for Further Study 32 APPENDIX A: SURVEY RESULTS AND IMPRESSIONS 33 REFERENCES 37 4 The 2012-2013 President’s Fellows with us to discuss the state of would like to thank University of civility at the University: Senior Vice Maryland, Baltimore President President and Dean Bruce Jarrell; Jay A.