Digital Technologies and Environmental Change Examining the Influence of Social Practices and Public Policies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Definition and Methods for the Carbon Handprint of Buildings

Definition and methods for the carbon handprint of buildings 8.2.2021 Authors: Tarja Häkkinen [email protected] Sylviane Nibel [email protected] Harpa Birgisdottir [email protected] 2 Table of contents 1 Background ..................................................................................................................... 4 2 Objectives........................................................................................................................ 7 3 Methods and execution of work ...................................................................................... 8 Study of literature ................................................................................................................... 8 Study of possible handprint cases for buildings ..................................................................... 9 Study of relevant standards .................................................................................................. 10 4 Study of literature.......................................................................................................... 11 Definitions and approaches .................................................................................................. 11 Handprint thinking................................................................................................................ 13 Needs and barriers for the handprint concept ..................................................................... 14 Measures that improve carbon handprint .......................................................................... -

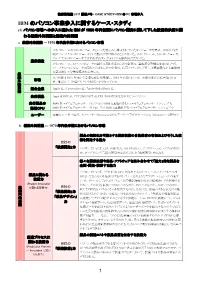

IBM のパソコン事業参入に関するケース・スタディ (1) パソコン市場への参入に遅れた IBM が 1980 年代初頭にパソコン開発に関して下した技術的決断に関 わる組織外的要因と組織内的要因 A

技術戦略論 2011 講義メモ> CASE STUDY>IBM の PC 市場参入 IBM のパソコン事業参入に関するケース・スタディ (1) パソコン市場への参入に遅れた IBM が 1980 年代初頭にパソコン開発に関して下した技術的決断に関 わる組織外的要因と組織内的要因 a. 組織外的要因 --- 1970 年代後半期におけるパソコン市場 メインフレームやミニ・コンピュータといった製品から構成されていたコンピュータ産業に、1970 年代中 頃にパーソナル・コンピュータという製品が付け加わることになった。メインフレーム、ミニ・コンピュータ、 パーソナル・コンピュータではそれぞれターゲットとする顧客層が異なった。 産業構造 メインフレーム、ミニ・コンピュータの製造に関わるほとんどの企業は、垂直統合型構造を志向したが、 パーソナル・コンピュータに関わったほとんどの企業は、応用ソフト、OS、CPU、記憶装置など主要構成 要素に関して分業型構造を志向した。 組 織 PC 市場は 1975 年頃から急激な成長を開始し、1981 年の米国パソコン市場は推定出荷台数 70 万 市場 外 台、推定売上 10 億ドルという規模にまでなっていた。 的 要 競合企業 Apple 社、Commodore 社、Tandy=RadioShack 社 因 先行製品 AppleII(1977.4)、PET 2001(1977.4)、TRS-80(1977.8)などの 8 ビットパソコン 先行製品の 8080 系マイクロプロセッサー(インテルの 8080 と互換性を持つマイクロプロセッサー)>シェア大 採用CPU 6800 系マイクロプロセッサー(モトローラの 6800 と互換性を持つマイクロプロセッサー)>シェア小 ユーザー 主要なユーザー層が、イノベーター(Innovators)からアーリー・アダプター(Early Adopters)へと移行中 b. 組織外的要因 --- 1970 年代後半期におけるパソコン市場 製品の差別化を可能とする要素技術の自社保有の有無およびそうした技 術を開発する能力 自社の 「技術開発」力 パソコンでいえば、CPU の開発力、OS の開発力、アプリケーション・ソフトの開発 力、プログラミング言語の開発力などがこうした「技術開発」力になる 様々な要素技術や部品・ソフトウェアを組み合わせて「魅力」的な製品を 企画・開発・設計する能力 パソコンでいえば、「どのような CPU を採用するのか?」、「プレ・インストール用 製品に関わる OS としてどんな OS を採用するのか?」、「どのようなアプリケーション・ソフトをプ 技術力 レ・インストールしておくのか?」、「周辺機器接続のための拡張カードを利用する (Product Innovation ために、どのような拡張バス(ISA バスなのか、PCI バスなのか、AGP バスなのか、 組 に関わる技術力) 自社の PCI-EXPRESS バスなのか)を採用するのか、あるいは、拡張バスをどれだけの数 織 「製品開発」力 内 だけ設けるのか(あるいは拡張バスを設けないのか)?」、「外部周辺機器を簡単 的 「製品デザイン」 に接続してすぐに使うためにどのような接続ポート(ex.RS232C 接続ポート、ジョイ 要 力 スティック接続ポート、USB 接続ポート、IEEE1394 接続ポート、外部ディスプレイ 因 接続ポート)を採用するのか?」「どのようなマザーボードを採用するのか?」などと いった異なる複数の技術的方式の選択に関わる技術的判断を必要とする事柄に 関する能力 ----なお、 「どのような容量の HDD を採用するのか?」「FDD -

HTTP Cookie - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 14/05/2014

HTTP cookie - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 14/05/2014 Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Search HTTP cookie From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Navigation A cookie, also known as an HTTP cookie, web cookie, or browser HTTP Main page cookie, is a small piece of data sent from a website and stored in a Persistence · Compression · HTTPS · Contents user's web browser while the user is browsing that website. Every time Request methods Featured content the user loads the website, the browser sends the cookie back to the OPTIONS · GET · HEAD · POST · PUT · Current events server to notify the website of the user's previous activity.[1] Cookies DELETE · TRACE · CONNECT · PATCH · Random article Donate to Wikipedia were designed to be a reliable mechanism for websites to remember Header fields Wikimedia Shop stateful information (such as items in a shopping cart) or to record the Cookie · ETag · Location · HTTP referer · DNT user's browsing activity (including clicking particular buttons, logging in, · X-Forwarded-For · Interaction or recording which pages were visited by the user as far back as months Status codes or years ago). 301 Moved Permanently · 302 Found · Help 303 See Other · 403 Forbidden · About Wikipedia Although cookies cannot carry viruses, and cannot install malware on 404 Not Found · [2] Community portal the host computer, tracking cookies and especially third-party v · t · e · Recent changes tracking cookies are commonly used as ways to compile long-term Contact page records of individuals' browsing histories—a potential privacy concern that prompted European[3] and U.S. -

1977: the Year of the Appliance Computer

1977: The year of the appliance computer Vintage Computer Festival East Sunday, April 2, 2017 Bill Degnan The MITS Mobile Computer Carivan traveled across the USA to demonstrate and teach customers about the MITS Altair, and to help customers with their kit project work. There has to be an easier way! Cover, Byte December 1977 Computer Lib / Dream Machines by Theodor Nelson 1977 a Nexus? • Customer demand for user-friendly computers. • Larger Manufacturers with finished systems entering the market • Mass production • Finished Systems well below $2000 • Multiple PC magazines • Special Interest Groups/Clubs/Conventions Enter The “Appliance Computer” • Phrase coined by Carl Helmers, Byte editor in January 1977 • Finished product desktop general-purpose computer complete with software (BASIC) • Reasonably Priced, purchased at a retail store or computer shop • Turnkey Computer – Works right out of the box • User does not need to know electronics or techniques of tuning of hardware • User does not need to build custom bootstrap program to initiate system • User manual uses pictures and examples to teach use, designed for simplicity. • The point of ownership is not to build the computer and maintain it Appliance computers for small business? You Bet! • A single computer is used in a very small business to take the place of several people either by saving the cost of salaries and benefits or freeing people for other tasks. • Eliminates manual processing of clerical work – inventory, book keeping, spreadsheets, production control, automated process monitoring and measuring, elimination of other paper shuffling. • New capabilities like presentations, mailing lists and other customer sorting, telephone files, library catalogs other databases. -

Discontinued Browsers List

Discontinued Browsers List Look back into history at the fallen windows of yesteryear. Welcome to the dead pool. We include both officially discontinued, as well as those that have not updated. If you are interested in browsers that still work, try our big browser list. All links open in new windows. 1. Abaco (discontinued) http://lab-fgb.com/abaco 2. Acoo (last updated 2009) http://www.acoobrowser.com 3. Amaya (discontinued 2013) https://www.w3.org/Amaya 4. AOL Explorer (discontinued 2006) https://www.aol.com 5. AMosaic (discontinued in 2006) No website 6. Arachne (last updated 2013) http://www.glennmcc.org 7. Arena (discontinued in 1998) https://www.w3.org/Arena 8. Ariadna (discontinued in 1998) http://www.ariadna.ru 9. Arora (discontinued in 2011) https://github.com/Arora/arora 10. AWeb (last updated 2001) http://www.amitrix.com/aweb.html 11. Baidu (discontinued 2019) https://liulanqi.baidu.com 12. Beamrise (last updated 2014) http://www.sien.com 13. Beonex Communicator (discontinued in 2004) https://www.beonex.com 14. BlackHawk (last updated 2015) http://www.netgate.sk/blackhawk 15. Bolt (discontinued 2011) No website 16. Browse3d (last updated 2005) http://www.browse3d.com 17. Browzar (last updated 2013) http://www.browzar.com 18. Camino (discontinued in 2013) http://caminobrowser.org 19. Classilla (last updated 2014) https://www.floodgap.com/software/classilla 20. CometBird (discontinued 2015) http://www.cometbird.com 21. Conkeror (last updated 2016) http://conkeror.org 22. Crazy Browser (last updated 2013) No website 23. Deepnet Explorer (discontinued in 2006) http://www.deepnetexplorer.com 24. Enigma (last updated 2012) No website 25. -

Stefan N. Grösser Arcadio Reyes-Lecuona Göran Granholm

Stefan N. Grösser Arcadio Reyes-Lecuona Göran Granholm Editors Dynamics of Long-Life Assets From Technology Adaptation to Upgrading the Business Model Dynamics of Long-Life Assets Stefan N. Grösser • Arcadio Reyes-Lecuona Göran Granholm Editors Dynamics of Long-Life Assets From Technology Adaptation to Upgrading the Business Model Editors Stefan N. Grösser Göran Granholm School of Management VTT Technical Research Centre Bern University of Applied Sciences of Finland Ltd. Bern Espoo Switzerland Finland Arcadio Reyes-Lecuona E.T.S.I. de Telecomunicación Universidad de Málaga Málaga Spain ISBN 978-3-319-45437-5 ISBN 978-3-319-45438-2 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-45438-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017932015 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and the Author(s) 2017. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the book’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the book's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. -

Retrocomputer Magazine

Jurassic News Retrocomputing: Buon compleanno tre scuole di Spectrum! pensiero, un solo movimento C R La storia del BASIC A Y 1 Le mostre Torino: Steve Jobs 1955-2011 Bertiolo 2012 Apple Club: il miniBASIC Trento: Era domani Retrocomputer Magazine Anno 7 - Numero 41 - Maggio 2012 Collophon I dati editoriali della rivista Jurassic News Jurassic News Rivista aperiodica di Retrocomputer Jurassic News Coordinatore editoriale: Tullio Nicolussi [Tn] E’ una fanzine dedicata al retro- Redazione: computing nella più ampia accezione del [email protected] termine. Gli articoli trattano in generale dell’informatica a partire dai primi anni Hanno collaborato a questo numero: ‘80 e si spingono fino ...all’altro ieri. Besdelsec [Bs] Lorenzo [L2] La pubblicazione ha carattere Sonicher [Sn] puramente amatoriale e didattico, tutte Salvatore Macomer [Sm] Lorenzo Paolini [Lp] le informazioni sono tratte da materiale Giovanni [jb72] originale dell’epoca o raccolte su Internet. Antonio Tierno Cecilia Botta Normalmente il materiale originale, Moira Bertolini anche se “giurassico” in termini Felice Pescatore informatici, non è privo di restrizioni di Luca Papinutti utilizzo, pertanto non sempre è possibile Damiano Cavicchio Massimo Cellini riportare per intero articoli, foto, schemi, listati, etc…, che non siano esplicitamente Diffusione: liberi da diritti. La rivista viene diffusa in formato PDF via Internet agli utenti E’ possibile che parti del materiale registrati sul sito: pubblicato derivi da siti internet che non sono citati direttamente negli articoli. www.jurassicnews.com. Questo per la difficoltà di attribuzione del Contatti: materiale alla fonte originale; eventuali [email protected] segnalazioni e relative notifiche sono benvenute. Copyright: I marchi citati sono di copyrights La redazione e gli autori degli dei rispettivi proprietari. -

Las Netbook En Educación

Las Netbook en Educación PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Sun, 10 Jun 2012 00:15:15 UTC Contents Articles Historia de las computadoras personales 1 Internet 19 Netbook 28 Tecnologías de la información y la comunicación 31 Web 2.0 53 Docencia 2.0 57 Conectar Igualdad 58 References Article Sources and Contributors 60 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 61 Article Licenses Licencia 63 Historia de las computadoras personales 1 Historia de las computadoras personales La historia de las computadoras personales comenzó en los años 1970. Una computadora personal esta orientado al uso individual y se diferencia de una computadora mainframe, donde las peticiones del usuario final son filtradas a través del personal de operación o un sistema de tiempo compartido, en el cual un procesador grande es compartido por muchos individuos. Después del desarrollo del microprocesador, las computadoras personales llegaron a ser más económicos y se popularizaron. Niños jugando en una computadora Amstrad CPC 464 en los años 1980 Las primeras computadoras personales, generalmente llamados microcomputadoras, fueron vendidos a menudo como kit electrónicos y en números limitados. Fueron de interés principalmente para los aficionados y técnicos. Etimología Originalmente el término "computadora personal" apareció en un artículo del New York Times el 3 de noviembre de 1962, informando de la visión de John W. Mauchly sobre el futuro de la computación, según lo detallado en una -

Automatic Monitoring for Interactive Performance and Power Reduction

Automatic Monitoring for Interactive Performance and Power Reduction by Krisztián Flautner A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Computer Science and Engineering) in The University of Michigan 2001 Doctoral Committee: Professor Trevor Mudge, Chair Assistant Professor Todd M. Austin Professor Kenneth G. Powell Assistant Professor Steven K. Reinhardt Assistant Professor Gary Tyson Krisztián Flautner © 2001 All Rights Reserved To my grandmother, Eleonóra Majorosy. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my mother, Eleonóra Arató who, at first sceptical of me spending too much time with a brand new Commodore 64, eventually gave up trying to push me towards medical school and has been a steadfast supporter of my studies ever since. My wife, Krisztina Gerhardt helped me gather the focus to finish this dissertation. I thank my stepfather, Cecil Eby, whose adventures with computers have shown me time again that even simple triumphs over the machine can bring great satisfaction. The research that eventually led to this dissertation began under Rich Uhlig’s watch while I was at the Intel Microprocessor Research Lab in Portland, Oregon. His comments and ideas greatly influenced the initial direction. Steve Reinhardt has been very helpful at getting to the bottom of the issues and forcing me to elaborate on the details. Conversations with and the compiler course taught by Peter Bird had a great impact on my view of computers. I would like to thank him for many afternoons’ worth of interesting discussions. I would also like to thank my fellow graduate students, Matt Pos- tiff and David Greene, who have been willing and helpful test subjects for many of the ideas in this dissertation. -

IBM 5100 APL Reference Manual

Preface This publication is a reference manual that provides specific information about the use of the IBM 5100 Portable Computer, the APL language, and installation planning and procedures. It also provides information about forms insertion and ribbon replacement for the 5103 printer. This publication is intended for users of the 5100 and the APL language. Prerequisite Pub1icat ion IBM 5100 APL Introduction, SA21-9212 Related Publications IBM 5100 APL Reference Card, GX21-9214 APL Language, GC26-3847 IBM 5100 Communications Reference Manual, SA2 1-9215 0 First Edition (August 1979) 0 Changes are continually made to the specifications herein; any such changes will be reported in subsequent revisions or technical newsletters. Requests for copies of IBM publications should be made to your IBM represen- tative or the IBM branch office serving your locality. 0 A form for reader's comments is at the back of this publication. If the form has been removed, address your comments to IBM Corporation, Publications, Dept. 245, Rochester, Minnesota 55901. @ Copyright International Business Machines Corporation, 1975 0 Contents CHAPTER 1. OPERATION ......... 1 CHAPTER 4. PRIMITIVE (BUILT-IN) FUNCTIONS . .43 I8M 5100 Overview ............ 1 Primitive Scalar Functions ..........43 Display Screen ............. 1 The + Function: Conjugate. Plus .......44 . Switches ............... 4 The- Function: Negation. Minus ..... .45 (-. i Power On or Restart Procedures ....... 4 The x Function: Signum. Times ...... .46 Display Screen Control .......... 5 The + Function: Reciprocal. Divide ..... .48 Keyboard .............. 6 The r Function: Ceiling. Maximum ......50 Attention ............. 6 The L Function: Floor. Minimum ..... .51 Hold ............... 6 The I Function: Magnitude. Residue .....52 Execute .............. 7 The *Function: Exponential. Power .... .54 Command ............ -

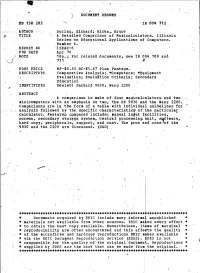

A Detailed Comparison of Maxicalculators. Illinois Series on Educational Applications of Computers

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 138 283 IR 004 712 AUTHOR • Doring, Richard; Hicks, Bruce TITLE A Detailed Comparison of Maxicalculators. Illinois Series on Educational Applications of Computers. Number 6. REPORT NO •I SEAC-6 PUB DATE Apr 76 NOTE 18p.; For related documents, see IR 004 709 and 711 EDRS PRICE 8F-$0.83 HC-$1.67 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Comparative Analysis;.*Computers; *Equipment Evaluation; Evaluátion Criteria; Secondary Edcàtioíi IDENTIFIERS Hewlett Packard 9830; Wang 2200 ABSTRACT A comparison is made of four maxicalculators a-nd two minicomputers with an emphasis on two, the HP 9830 and the Wang 2200. Comparisons are im the form of a table with individual guidelines for analysis followed by the specific characteristics of the particular calculator. Features compared include: manual input facilities, screen, secondary storage system, central processing unit, software, hard copy, peripherals, support, and cost. The pros and cons of the 9830 and the 2200 are discussed. (DAG) Number 6 The Illinois Series on Educational Applications of Computers A DETAILED COMPARISON OF MAXICALCULATORS Richard Doring and Bruce Hicks April 1976 Department of Secondary Education College of Education University of Illinois Urbana, Illinois O Bruce Hicks (1976) Preface Maxicalculators (and their peripherals) are one type of small computer system. Even though these systems are small, the choice among them is still not a simple matter when the maxicalculators are to be used with the greatest effectiveness in educational applications, for then they must serve a great variety of students, teachers and administrators and in many different modes of operation. Our discussion of the choice among maxicalculators,concerns-two aspects: a) the capabilities of maxicalculators for the whole school; b) an example of a detailed comparison between two maxicalculators. -

13 Critical Machines

THEBIRTHOFTHENOTEBOOK History has a way of reinventing itself. Like modern computer. Oh, and it weighed 2 pounds. Michael Jackson, the past makes strange and The only catch was that the Dynabook didn’t exist. The sometimes hideous transformations — and, as technology it required simply hadn’t been invented yet. At with Jacko, it’s not always easy to fi gure out what the time, only primitive LCD and plasma displays were being exactly happened. tinkered with, and the technology for one wireless modem took THEBIRTHOF Who invented the telephone? Was it Alexander Graham up half of an Econoline van. Bell or Elisha Gray? The Wright brothers made the fi rst fl ight The closest Kay ever got to building the Dynabook was a in a passenger plane, but what about Otto Lilienthal, whose cardboard mock-up fi lled with lead pellets. gliders infl uenced the brothers in their quest? From the game of chess to the pinball machine to the fortune cookie, the THE MINIATURE MAINFRAME THENOTEBOOK birth of countless famous products is a matter for debate. One of the factors keeping Xerox from working on the Dynabook And so it is with the portable computer. Who’s responsible was the market, which at the time could be summed up in one Mobile PC takes you on the strange and harrowing for pioneering the biggest shift in PC technology since the word: IBM. The computing giant had swallowed an astonishing punch card gave way to the magnetic disk? 81-percent share of the computer market by 1961, quashing journey to the origins of portable computing It depends on whom you ask.