A Guide to This Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USGS 7.5-Minute Image Map for Matanzas Inlet, Florida

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR MATANZAS INLET QUADRANGLE U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY FLORIDA T9S 7.5-MINUTE SERIES 81°15' 12'30" 10' 81°07' 30" IntracoastalR30E4 000m Waterway 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 29°45' 76 E 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 610 000 FEET 86 87 29°45' 3291000mN 3291 FLORIDA 2 «¬A1 S Devils Elbow T . r J e O v H i R N S S s s 11 32 32 a C 90 90 z O n a t a M Anastasia Island 3289 3289 12 1 960 000 FEET «¬A1 3288 3288 T9S R30E 13 Fort 3287 Matanzas 3287 FORT MATANZAS NATIONAL MONUMENT 24 Imagery................................................NAIP, January 2010 Roads..............................................©2006-2010 Tele Atlas Names...............................................................GNIS, 2010 42'30" 42'30" Hydrography.................National Hydrography Dataset, 2010 Contours............................National Elevation Dataset, 2010 Claude Varne ATLANTIC Bridge Matanzas Inlet OCEAN 3286 3286 DR RIA TA RA AR B G E N E E Rattlesnake J RD Summer Haven O SON Island HN OLD A1A J U N E E A1 32 32 L «¬ 85 85 N M a t a n z a s s R i v e r 3284 3284 3283 3283 ST. JOHNS CO FLAGLER CO «¬A1 3282 Intracoastal Waterway 3282 40' 40' Hemming Point N N O C E A N Marineland S H O R E E B r L V e D v i 32 R DEERWOOD ST 3281 81 2 s a BEACHSIDE DR k z e n e a r t C a r r M e SHADY OAK LN c i . -

Intracoastal Waterway, Jacksonville to Miami, Florida: Maintenance Dredging

FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT INTRACOASTAL WATERWAY, JACKSONVILLE, FLORIDA, TO MIAMI, FLORIDA MAINTENANCE DREDGING Prepared by U. S. Army Engineer District, Jacksonville Jacksonville, Florida May 1974 INTRACOASTAL WATERWAY. JACKSONVILLE TO MIAMI MAINTENANCE DREDGING ( ) Draft (X) Final Responsible Office: U. S. Army Engineer District, Jacksonville, Florida. 1. Name of Action: (X) Administrative ( ) Legislative 2. Description of Action: Eleven shoals are to be removed from this section of the Intracoastal Waterway as a part of the regular main tenance program. 3. a. Environmental Impacts. About 172,200 cubic yards of shoal material in the channel will be removed by hydraulic dredge and placed in diked upland areas and as nourishment on a county park beach south of Jupiter Inlet. b. Adverse Environmental Effects. Dredging will have a temporary adverse effect on water quality and will destroy benthic organisms in both the shoal material and on the beach. In addition, some turtle nests at the beach nourishment site may be destroyed. 4. Alternatives. Consideration was given to alternate methods of spoil disposal. It was determined that the methods selected (as described in paragraph 1) would best accomplish the purpose of the project while minimizing adverse impact on the environment. 5. Comments received on the draft statement in response to the 3 November 1972 coordination letter: Respondent Date of Comments U. S. Coast Guard 7 November 1972 U. S. Department of Agriculture 8 November 1972 Florida State Museum 8 November 1972 Florida Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services 14 November 1972 Florida Department of Transportation 20 November 1972 Florida Department of Natural Resources 30 November 1972 Environmental Protection Agency 8 December 1972 Florida G&FWFC 13 December 1972 U. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB NO. 1024-0018 Expires 10-31-87 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS us« only ._ MAY 27 1986 National Register off Historic Places received ll0 Inventory Nomination Form date entered &> A// J^ See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name historic St. Augustine Historic District and or common 2. Location N/A street & number __ not for publication St. Augustine city, town vicinity of Florida state code 12 county St. Johns code 109 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use x district public occupied agriculture X museum building(s) private X unoccupied ^ commercial X .park structure X both work in progress X educational X . private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible X entertainment X religious object in process yes: restricted X government scientific being considered X yes: unrestricted industrial transportation x military . other: 4. Owner off Property name Multiple street & number N/A St. Augustine N/A city, town vicinity of state Florida 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. St. Johns County Courthouse street & number 95 Cordova Street city, town St. Augustine state Florida 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title St. Augustine Survey has this property been determined eligible? X yes __ no date 1978-1986 federal X state county local depository for survey records Florida Department of State; Hist. St. Augustine Preservation Bd, city, town Tallahassee and St. Augustine state Florida 7. Description Condition Check one Check one ___4;ejteeHent . deteriorated unaltered original site OOOu ruins altered moved date __ fair unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance SUMMARY OF PRESENT AND ORIGINAL PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The revised St. -

12 TOP BEACHES Amelia Island, Jacksonville & St

SUMMER 2014 THE COMPLETE GUIDE TO GO® First Coast ® wheretraveler.com 12 TOP BEACHES Amelia Island, Jacksonville & St. Augustine Plus: HANDS-ON, HISTORIC ATTRACTIONS SHOPPING, GOLF & DINING GUIDES JAXWM_1406SU_Cover.indd 1 5/30/14 2:17:15 PM JAXWM_1406SU_FullPages.indd 2 5/19/14 3:01:04 PM JAXWM_1406SU_FullPages.indd 1 5/19/14 2:59:15 PM First Coast Summer 2014 CONTENTS SEE MORE OF THE FIRST COAST AT WHERETRAVELER.COM The Plan The Guide Let’s get started The best of the First Coast SHOPPING 4 Editor’s Itinerary 28 From the scenic St. Johns River to the beautiful Atlantic Your guide to great, beaches, we share our tips local shopping, from for getting out on the water. Jacksonville’s St. Johns Avenue and San Marco Square to King Street in St. Augustine and Centre Street in Amelia Island. 6 Hot Dates Summer is a season of cel- ebrations, from fireworks to farmers markets and 32 MUSEUMS & concerts on the beach. ATTRACTIONS Tour Old Town St. 48 My First Coast Augustine in grand Cindy Stavely 10 style in your very own Meet the person behind horse-drawn carriage. St. Augustine’s Pirate Museum, Colonial Quarter 14 DINING & and First Colony. Where Now NIGHTLIFE 46..&3 5)&$0.1-&5&(6*%&50(0 First Coast ® Fresh shrimp just tastes like summer. Find out wheretraveler.com 9 Amelia Island 12 TO P BEACHES where to dig in and Amelia Island, Jacksonville & St. Augustine From the natural and the historic to the posh and get your hands dirty. luxurious, Amelia Island’s beaches off er something for every traveler. -

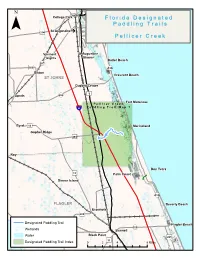

Pellicer Creek Paddling Guide

Saint Augustine College Park F ll o r ii d a D e s ii g n a tt e d P a d d ll ii n g T r a ii ll s ¯ CR 312 St Augustine Á )"214 «¬ CR«¬ A1A P e ll ll ii c e r C r e e k Vermont St Augustine Heights Shores Butler Beach «¬207 )"305 A«¬1A Elkton Crescent Beach ST JOHNS Dupont Center 1 Spuds «¬206 ¤£ Fort Matanzas P e ll ll ii c e rr C rr e e k ¨¦§95 P a d d ll ii n g T rr a ii ll M a p 1 Byrd )"13 Marineland Gopher Ridge )"204 Roy Bon Terra )"13 Palm Coast Dinner Island A«¬1A FLAGLER Beverly Beach Espanola )"205 Designated Paddling Trail SR 20 SR 100 Flagler Beach «¬ «¬ «¬100 Wetlands Bunnell Water Black Point CR«¬ 305 )"201 11 Designated Paddling TCraR)"i l 3I0n5dex 0 2 )" 4 8 Miles P e ll ll ii c e rr C rr e e k P a d d ll ii n g T rr a ii ll Matanzas State Forest Fort Matanzas National Monument ¯ Fort Matanzas A«¬1A Faver-Dykes State Park G u a n a T o l o m a t o M Access Point 1: Faver Dykes State Park a Marineland t a N: 29.6674 W: -81.2574 n z a s N Þ a t !9 !| i *I o k n e a e l F A r E V s E C er t R lic u D el a Y P r K i E n S e R D R e s Þ e 204 !9 !| a )" 1 *I r ¤£ c h R e s D e R r S Princess Place v E e N C Preserve H R A L E P O L J S S G Pellicer Creek Conservation Area E T A C S N L I F R P ¨¦§95 Access Point 2: Princess Place Preserve N: 29.6564 W: -81.2356 Pellicer Creek Paddling Trail Canoe/Kayak Launch O !| L D K Restrooms IN *I G S R !9 Camping D Þ Potable Water Florida Conservation Lands State Parks MA TANZAS W OOD S P Wetlands KWY 0 0.5 1 2 Miles Pellicer Creek Paddling Trail Guide The Waterway Pellicer Creek is one of the most pristine estuarine tidal marshes on the east coast of Florida with abundant salt and fresh water fish, and excellent wildlife viewing. -

Florida Department of Environmental Protection - Conservation Land Assessment Proposed Surplus Sites August 20, 2013

Florida Department of Environmental Protection - Conservation Land Assessment Proposed Surplus Sites August 20, 2013 State-Owned Acres Conservation Area Site Reference ID (GIS) County Section-Township-Range Allen David Broussard Catfish Creek Preserve State Park DRP-4 3.4 Polk County Section 018, Township 29-S, Range 29-E DRP-5 2.0 Polk County Section 018, Township 29-S, Range 29-E Anastasia State Park DRP-0 2.7 St. Johns County Section 021, Township 07-S, Range 30-E Atlantic Ridge Preserve State Park DRP-1 12.6 Martin County Section 34, Township 38-S, Range 42-E Avalon State Park DRP-2 2.2 St. Lucie County Section 03, Township 34-S, Range 40-E DRP-3 6.6 St. Lucie County Section 03, Township 34-S, Range 40-E Big Bend Wildlife Management Area FWC-BB 1 3.4 Dixie County Section 24, Township 10-S, Range 09-E FWC-BB 2 5.3 Dixie County Section 23, Township 10-S, Range 09-E Blackwater Heritage State Trail DRP-59 4.8 Santa Rosa County Section 010, Township 01-N, Range 28-W Blue Spring State Park FLMA_16 22.4 Volusia County Section 08, Township 18-S, Range 30-E Box-R Wildlife Management Area FWC-BX 1 26.0 Franklin County Section 021, Township 08-S, Range 08-W Bruner Bay Tract CF-836-25 43.9 Washington County Section 028, Township 03-S, Range 15-W Cayo Costa State Park DRP-10 0.2 Lee County Section 29, Township 44-S, Range 21-E DRP-11 0.1 Lee County Section 32, Township 44-S, Range 21-E DRP-12 0.2 Lee County Section 05, Township 45-S, Range 21-E DRP-13 0.4 Lee County Section 05, Township 45-S, Range 21-E DRP-14 0.2 Lee County Section 05, Township -

Upland Invasive Exotic Plant Control Program Fiscal Year 2016-2017 Summary

Upland Invasive Exotic Plant Control Program Fiscal Year 2016-2017 Summary Over one-and-one-half million acres of Florida’s public conservation land have been invaded by alien (exotic, nonnative, nonindigenous) plants such as melaleuca, Brazilian pepper, cogon grass, and climbing ferns. However, invasive alien plants respect no boundaries and millions of acres of agricultural and private land are also been affected. Florida’s nearly 11 million acres of public conservation land support a nature-based tourism economy valued at $10 billion annually (total tourism spending in 2015 equaled $89 billion). The Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission’s Invasive Plant Management Section (IPMS) is the designated lead entity in Florida responsible for coordinating and funding the statewide control of invasive aquatic and upland plants in public waterways and on public conservation land. The Upland Invasive Exotic Plant Management Program (a subsection of IPMS) was established in 1997 to address the need for a statewide coordinated approach to the terrestrial (vs. aquatic) invasive exotic plant problem. The “Uplands Program” incorporates place-based management concepts, bringing together regionally diverse interests to develop flexible, innovative strategies to address weed management issues at the local level. The program funds individual exotic plant removal projects statewide on public conservation land. Projects are considered for funding based upon recommendations from eleven Regional Invasive Plant Working Groups. The mission of the Uplands Program is to achieve maintenance control of invasive exotic plants like cogon grass (Imperata cylindrica), melaleuca (Melaleuca quinquenervia), Brazilian pepper (Schinus terebinthifolius), Old World climbing fern (Lygodium microphyllum), and Japanese climbing fern (L. japonicum) on public conservation land. -

The Elkton Hastings Historic Farmstead Survey, St

THE ELKTON HASTINGS HISTORIC FARMSTEAD SURVEY, ST. JOHNS COUNTY, FLORIDA Prepared For: St. Johns County Board of County Commissioners 2740 Industry Center Road St. Augustine, Florida 32084 May 2009 4104 St. Augustine Road Jacksonville, Florida 32207- 6609 www.bland.cc Bland & Associates, Inc. Archaeological and Historic Preservation Consultants Jacksonville, Florida Charleston, South Carolina Atlanta, Georgia THE ELKTON HASTINGS HISTORIC FARMSTEAD SURVEY, ST. JOHNS COUNTY, FLORIDA Prepared for: St. Johns County Board of County Commissioners St. Johns County Miscellaneous Contract (2008) By: Myles C. P. Bland, RPA and Sidney P. Johnston, MA BAIJ08010498.01 BAI Report of Investigations No. 415 May 2009 4104 St. Augustine Road Jacksonville, Florida 32207- 6609 www.bland.cc Bland & Associates, Inc. Archaeological and Historic Preservation Consultants Atlanta, Georgia Charleston, South Carolina Jacksonville, Florida MANAGEMENT SUMMARY This project was initiated in August of 2008 by Bland & Associates, Incorporated (BAI) of Jacksonville, Florida. The goal of this project was to identify and record a specific type of historic resource located within rural areas of St. Johns County in the general vicinity of Elkton and Hastings. This assessment was specifically designed to examine structures listed on the St. Johns County Property Appraiser’s website as being built prior to 1920. The survey excluded the area of incorporated Hastings. The survey goals were to develop a historic context for the farmhouses in the area, and to make an assessment of the farmhouses with an emphasis towards individual and thematic National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) potential. Florida Master Site File (FMSF) forms in a SMARTFORM II database format were completed on all newly surveyed structures, and updated on all previously recorded structures within the survey area. -

Fort Matanzas National Monument Digital Documentation Project:Â

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Heritage and Humanities Collections Faculty and Staff Publications Tampa Library 8-2013 Fort Matanzas National Monument Digital Documentation Project: Utilizing Terrestrial Lidar For The Understanding Of Structural Integrity Concerns For Coastal Forts And Coquina Structures (Cesu,National Park Service) Lori D. Collins University of South Florida, [email protected] Travis F. Doering University of South Florida, [email protected] Jorge Gonzalez University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/dhhc_facpub Scholar Commons Citation Collins, Lori D.; Doering, Travis F.; and Gonzalez, Jorge, "Fort Matanzas National Monument Digital Documentation Project: Utilizing Terrestrial Lidar For The Understanding Of Structural Integrity Concerns For Coastal Forts And Coquina Structures (Cesu,National Park Service)" (2013). Digital Heritage and Humanities Collections Faculty and Staff Publications. 3. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/dhhc_facpub/3 This Technical Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Tampa Library at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Heritage and Humanities Collections Faculty and Staff Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FORT MATANZAS NATIONAL MONUMENT DIGITAL DOCUMENTATION PROJECT: UTILIZING TERRESTRIAL LIDAR FOR THE UNDERSTANDING OF STRUCTURAL INTEGRITY CONCERNS FOR COASTAL FORTS AND COQUINA STRUCTURES (CESU, NATIONAL PARK SERVICE) LORI COLLINS, PH.D. AND TRAVIS DOERING, PH.D., 8/2013 CONTRIBUTIONS BY: JORGE GONZALEZ, STEVEN FERNANDEZ, JAMES MCLEOD, AND JOSEPH EVANS Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank Dr. Margo Schwadron, Archeologist with the Southeast Archeological Center, who assisted with the planning, organizing, and implementation of this project and provided support, advice, and suggestions throughout the process. -

National List of Beaches 2004 (PDF)

National List of Beaches March 2004 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Water 1200 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington DC 20460 EPA-823-R-04-004 i Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1 States Alabama ............................................................................................................... 3 Alaska................................................................................................................... 6 California .............................................................................................................. 9 Connecticut .......................................................................................................... 17 Delaware .............................................................................................................. 21 Florida .................................................................................................................. 22 Georgia................................................................................................................. 36 Hawaii................................................................................................................... 38 Illinois ................................................................................................................... 45 Indiana.................................................................................................................. 47 Louisiana -

Appendix I: Critical Erosion Report 2018 State Hazard Mitigation Plan ______

Appendix I: Critical Erosion Report 2018 State Hazard Mitigation Plan _______________________________________________________________________________________ APPENDIX I: Critical Erosion Report _______________________________________________________________________________________ Florida Division of Emergency Management Critically Eroded Beaches In Florida Division of Water Resource Management Florida Department of Environmental Protection August 2016 2600 Blair Stone Rd., MS 3590 Tallahassee, FL 32399-3000 www.dep.state.fl.us Foreword This report provides an inventory of Florida’s erosion problem areas fronting on the Atlantic Ocean, Straits of Florida, Gulf of Mexico, and the roughly sixty-six coastal barrier tidal inlets. The erosion problem areas are classified as either critical or non-critical and county maps and tables are provided to depict the areas designated critically and non-critically eroded. Many areas have significant historic or contemporary erosion conditions, yet the erosion processes do not currently threaten public or private interests. These areas are therefore designated as non-critically eroded areas and require close monitoring in case conditions become critical. This report, originating in 1989, is periodically updated to include additions and deletions. All information is provided for planning purposes only and the user is cautioned to obtain the most recent erosion areas listing available in the updated critical erosion report of 2016 on pages 4 through 20 or refer to the specific county of interest listed -

1 Preserving the Legacy the Hotel

PRESERVING THE LEGACY THE HOTEL PONCE DE LEON AND FLAGLER COLLEGE By LESLEE F. KEYS A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2013 1 © 2013 Leslee F. Keys 2 To my maternal grandmother Lola Smith Oldham, independent, forthright and strong, who gave love, guidance and support to her eight grandchildren helping them to pursue their dreams. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My sincere appreciation is extended to my supervisory committee for their energy, encouragement, and enthusiasm: from the College of Design, Construction and Planning, committee chair Christopher Silver, Ph.D., FAICP, Dean; committee co-chair Roy Eugene Graham, FAIA, Beinecke-Reeves Distinguished Professor; and Herschel Shepard, FAIA, Professor Emeritus, Department of Architecture. Also, thanks are extended to external committee members Kathleen Deagan, Ph.D., Distinguished Research Professor Emeritus of Anthropology, Florida Museum of Natural History and John Nemmers, Archivist, Smathers Libraries. Your support and encouragement inspired this effort. I am grateful to Flagler College and especially to William T. Abare, Jr., Ed.D., President, who championed my endeavor and aided me in this pursuit; to Michael Gallen, Library Director, who indulged my unusual schedule and persistent requests; and to Peggy Dyess, his Administrative Assistant, who graciously secured hundreds of resources for me and remained enthusiastic over my progress. Thank you to my family, who increased in number over the years of this project, were surprised, supportive, and sources of much-needed interruptions: Evan and Tiffany Machnic and precocious grandsons Payton and Camden; Ethan Machnic and Erica Seery; Lyndon Keys, Debbie Schmidt, and Ashley Keys.