Between Subjectification and Objectification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Confessions of a Hol

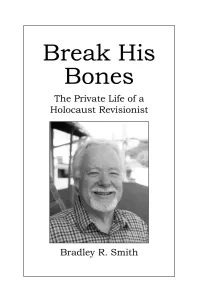

BREAK HIS BONES BREAK HIS BONES by Bradley R. Smith BRADLEY R. SMITH POST OFFICE BOX 439016 SAN YSIDRO, CALIFORNIA 92143 BREAK HIS BONES The Private Life of a Holocaust Revisionist by Bradley R. Smith First Printing: September 2002 Published by Bradley R. Smith Post Office Box 439016 San Ysidro, CA 92143 With the Assistance of Theses & Dissertations Press PO Box 64 Capshaw, AL 35742 ISBN 0-9723756-0-0 Copyright 2002 by Bradley R. Smith Printed in the United States of America AUTHOR’S NOTE It’s a truism. Things are different since 11 September 2001. Of course, things are always different, which is why the open-minded find life so mysterious. The mystery goes beyond mere unpredictability. We don’t know how we come into the world, never learn what we are or what happens to us when we’re finished. It’s been noted by an English sage that, as a matter of fact, we do not come into the world at all, that we come from the world. I am beguiled by the implica- tions of this observation. What it implies lifts up my heart, but this too is mysterious. After radical Islamists expressed their displeasure with American foreign policy at the World Trade Center and the Pentagon it was suggested by some that, having experi- enced our own holocaust, we would never talk about the Jewish Holocaust the way we had talked about it before. On the one hand that would be a mitzvah for those of us who do not personally represent the Holocaust Industry, or profit from it, and in any event do not want to hear about it any longer. -

The Memorial Monument

YIZKOR – THE MEMORIAL MONUMENT Blessed be God*, on the day 7th of Tamuz 5719 [13th July 1959], The Organisation of Krzepice and the Vicinity Jews in Israel and in the Diaspora Memorial Scroll We hereby commemorate the names of our dear ones and relatives who were annihilated in the years of the Holocaust. May this scroll be for an everlasting remembrance in the Capital of the World on Mount Zion, and may this monument serve as a headstone for all those who were murdered and were not brought to a Jewish grave. The Memorial Day has been set for the day 7th Tamuz; on this day, every year, we shall commune with all those who [once] were and are no longer to be found. ת.נ.צ.ב.ה. [May their souls be bound in the Bond of Life] Yizkor On 7th Tamuz 5719, when a monument was erected for the Krzepice Community in the Chamber of the Holocaust on Mount Zion in Jerusalem, a eulogy for the souls of the thousands of our dear Krzepice martyrs, was delivered by Mojsze‐Icek Monic. On the second day of the week [Monday], 7th Tamuz, 5719 [years] since the creation of the world, the eleventh year to the State of Israel and the seventeenth year since the destruction of our community – the Community of Krzepice, in the Częstochowa district, Poland ‐ we, the Jews of Krzepice and the vicinity in Israel, have gathered on Mount Zion in the Holy City of Jerusalem. [Here,] we have erected a memorial monument for the martyrs of our town and the vicinity, who perished at the hands of the Nazi foes and their accomplices, may their name be obliterated, on the day 7th Tamuz 5702 [22nd June 1942]. -

Between Subjectification and Objectification Theorizing Ashes Dziuban, Z

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Between Subjectification and Objectification Theorizing Ashes Dziuban, Z. Publication date 2017 Published in Mapping the 'Forensic Turn' Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Dziuban, Z. (2017). Between Subjectification and Objectification: Theorizing Ashes. In Z. Dziuban (Ed.), Mapping the 'Forensic Turn': Engagements with Materialities of Mass Death in Holocaust Studies and Beyond (pp. 261-288). (VWI zur Holocaustforschung; Vol. 5). New Academic Press. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:26 Sep 2021 Zuzanna Dziuban: Between Subjectification and Objectification Zuzanna Dziuban Between Subjectification and Objectification Theorising Ashes1 Disturbing Remains2 In November and December 2012, a small, one-person exhibition was held at a private gallery in the southern Swedish city of Lund, capturing rapt media attention and receiv- ing enormous international publicity. -

Introduction 1 Mourning Newspapers: Holocaust Commemoration And/ As

Notes Introduction 1. All translations were made by the authors. 2. We do not expand on the discussion of the origins of the word and its rela- tionship with other words, although others have written about it extensively. For example, Tal (1979) wrote an etymological analysis of the word in order to clarify its meaning in relation to the concept of genocide; Ofer (1996b) focused on the process by which the term ‘Shoah’ was adopted in British Mandate Palestine and Israel between 1942 and 1953, and explored its mean- ing in relation to concepts such as ‘heroism’ and ‘resurrection’; and Schiffrin’s works (2001a and 2001b) compare the use of Holocaust-related terms in the cases of the annihilation of European Jewry and the imprisonment of American Japanese in internment camps during the Second World War. See also Alexander (2001), who investigated the growing widespread use of the term ‘Shoah’ among non-Hebrew-speakers. 1 Mourning Newspapers: Holocaust Commemoration and/ as Nation-Building 1. Parts of this chapter have appeared in Zandberg (2010). 2. The Kaddish is a prayer that is part of the daily prayers but it is especially identified with commemorative rituals and said by mourners after the death of close relatives. 3. The Mishnah is the collection (63 tractates) of the codification of the Jewish Oral Law, the Halacha. 4. Knesset Proceedings, First Knesset, Third Sitting, 12 April 1952, Vol. 9, p. 1656. 5. Knesset Proceedings, Second Knesset, Fifth and Ninth Sittings, 25 February 1952, Vol. 11, p. 1409. 6. The 9 of Av (Tish’a B’Av) is a day of fasting and prayers commemorating the destruction of both the First and Second Temples in Jerusalem and the subsequent exile of the Jews from the Land of Israel. -

Guide for the New and Visiting Faculty

GUIDE FOR THE NEW AND FOR VISITING FACULTY GUIDE FOR THE NEW AND VISITING FACULTY Twelfth Edition The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Guide For The New And Visiting Faculty CONTENTS | 2 CONTENTS FOREWORD 3 The Pscyho-Educational Service 65 Health Services in Schools 65 CHAPTER ONE English for English Speakers 65 THE HEBREW UNIVERSITY OF JERUSALEM 4 Extracurricular Activities 66 The Adviser’s Office 4 Sports 66 Introduction to the Hebrew University of Jerusalem 5 Music and Art 66 The Edmond J. Safra (Givat Ram) Campus 6 Other Activities 67 The Ein Kerem Campus 7 Community Centers 67 The Rehovot Campus 7 Youth Movements 67 Libraries 8 Field Schools 68 Other University Units 12 Summer, Hanukkah and Passover Camps 68 The Rothberg International School 15 CHAPTER SIX International Degree Programs 18 UNIVERSITY, ADULT, AND CONTINUING EDUCATION 70 Non-Degree Graduate Programs 19 Academic Year 21 The Hebrew University of Jerusalem 70 Adult Education 71 CHAPTER TWO Hebrew Language Studies 72 FACILITIES ON CAMPUS 22 CHAPTER SEVEN Getting There 22 GETTING TO KNOW JERUSALEM: LIFESTYLE AND CULTURE 73 Security: Entry to Campus 24 Administration 26 General Information 73 Traditional and Religious Activities 30 Leisure Time 74 Academon 32 Touring Jerusalem 74 Performing Arts 76 CHAPTER THREE Cafés, Bars and Discotheques 76 PLANNING TO COME 40 Cinema 76 Visa Information 40 Media 77 Salaries and Taxes 42 Museums 78 Income Tax 42 Libraries 81 Value Added Tax (VAT/“ma’am”) 43 CHAPTER EIGHT National Insurance (Bituah Leumi) 43 OUT AND ABOUT IN JERUSALEM 82 -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Between Evidence and Symbol: The Auschwitz Album in Yad Vashem, the Imperial War Museum (London) and the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. by Jaime Ashworth Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2011 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Doctor of Philosophy BETWEEN EVIDENCE AND SYMBOL: THE AUSCHWITZ ALBUM IN YAD VASHEM, THE IMPERIAL WAR MUSEUM (LONDON) AND THE AUSCHWITZ-BIRKENAU STATE MUSEUM. by Jaime Ashworth This project explores the representation of the Holocaust in three museums: Yad Vashem in Jerusalem; the Imperial War Museum in London; and the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum in O świ ęcim, Poland. It uses the so-called Auschwitz Album, a collection of photographs taken in Birkenau in May 1944, as a case-study. -

Tracing and Documenting Nazi Victims Past and Present Arolsen Research Series

Tracing and Documenting Nazi Victims Past and Present Arolsen Research Series Edited by the Arolsen Archives – International Center on Nazi Persecution Volume 1 Tracing and Documenting Nazi Victims Past and Present Edited by Henning Borggräfe, Christian Höschler and Isabel Panek On behalf of the Arolsen Archives. The Arolsen Archives are funded by the German Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media (BKM). ISBN 978-3-11-066160-6 eBook (PDF) ISBN 978-3-11-066537-6 eBook (EPUB) ISBN 978-3-11-066165-1 ISSN 2699-7312 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial NoDerivatives 4.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licens-es/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2020932561 Bibliographic Information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2020 by the Arolsen Archives, Henning Borggräfe, Christian Höschler, and Isabel Panek, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Cover image: Jan-Eric Stephan Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Preface Tracing and documenting the victims of National Socialist persecution is atopic that has receivedlittle attention from historicalresearch so far.Inorder to take stock of existing knowledge and provide impetus for historicalresearch on this issue, the Arolsen Archives (formerlyknown as the International Tracing Service) organized an international conferenceonTracing and Documenting Victimsof Nazi Persecution: Historyofthe International Tracing Service (ITS) in Context. Held on October 8and 92018 in BadArolsen,Germany, this event also marked the seventieth anniversary of search bureaus from various European statesmeet- ing with the recentlyestablished International Tracing Service (ITS) in Arolsen, Germany, in the autumn of 1948. -

MODERN ISRAEL TOUR APRIL 19–30, 2020 FIRST FRUITS of ZION’S Experiencemodern ISRAEL TOUR Israel

ce Israel Experien FIRST FRUITS OF ZION’S MODERN ISRAEL TOUR APRIL 19–30, 2020 FIRST FRUITS OF ZION’S ExperienceMODERN ISRAEL TOUR Israel April 19–30 2020 Israelis from all walks of life will spend time with our Eleven days, including travel group and you will be astonished at the diversity of the culture. Experiences in a Bedouin village, in oin us for a unique and unforgettable journey a Samaritan town, on location at battle sites, in the through the land of Israel. You will be amazed mystical alleyways of Tzfat, inside Israel’s Knesset Jand delighted at the modernity of the country (parliament building), and on the sandy beaches as we experience post-1900s sites. Your heart will of Tel Aviv will deeply enhance your connection to be moved as we visit modern-day battle sites and the land and her people in ways that most tourists open our eyes to the reality of Israel’s militaristic never experience. society. This is your opportunity to truly touch the physical We will celebrate Israeli Independence Day among land and attach to her people. Come with us, and the people on the streets of Jerusalem and feel the be inspired at the beauty, productivity, coopera- mournful loss of Israel’s young sons, brothers, and tion, and ingenuity of this Modern-day Miracle: The friends on Memorial Day. No other tour will allow Land of Israel. you to experience Israel like this as we kayak the Jordan River, jeep the historic “Burma Road,” hike Visit ffoz.org/events, call 800-775-4807, or e-mail Israel’s dramatic desert mountains, participate in [email protected] for more information. -

Reconstructing Memory of the Debates And, Most Importantly, the Panorama of Opinions Revealed in the Process

5 The book aims to reconstruct and analyze the disputes over the Polish- Jewish past and memory in public debates in Poland between 1985 and 2012, Piotr Forecki from the discussions about Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah, Jan Bło´nski’s essay The Poor Poles Look at the Ghetto, Jan Tomasz Gross’ books Neighbours, Fear and Golden Harvest, to the controversies surrounding the premiere of Władysław Pasikowski’s The Aftermath. The analysis includes the course and dynamics Reconstructing Memory of the debates and, most importantly, the panorama of opinions revealed in the process. It embraces the debates held across the entire spectrum The Holocaust in Polish Public Debates of the national press. The selection of press was not limited by the level of circulation or a subjective opinion of their value. The main intention was to reconstruct the widest possible variety of opinions that were revealed during the debates. Broad symbolic elites participated in the debates: people who exercised control over publicly accessible knowledge, legitimacy of beliefs and the content of public discourse. GESCHICHTE ERINNERUNG POLITIK Piotr Forecki, PhD, is Assistant Professor of the Section of Political Culture Posener Studien zur Geschichts-, at the Faculty of Political Science and Journalism of the Adam Mickiewicz University in Pozna´n (Poland). He is a member of the Jewish Historical Insti- Kultur- und Politikwissenschaft tute Association. His academic research concerns the Polish memory of the Herausgegeben von Anna Wolff-Powe˛ska Holocaust, the representation of -

Yom Yerushalayim on Bill Clinton and the Entertainment Culture and Shavuot Edition

DIGITAL EDITION VOLUME 3 • ISSUE 2 אייר תש"ף TORAT ERETZ YISRAEL • PUBLISHED IN JERUSALEM • DISTRIBUTED AROUND THE WORLD MAY 2020 ISRAEL EDITION WITH GRATEFUL THANKS TO THE FOUNDING SPONSORS OF HAMIZRACHI – THE LAMM FAMILY OF MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA Senator Joe Lieberman Yom Yerushalayim on Bill Clinton and the Entertainment Culture and Shavuot Edition PAGE 42 Rabbanit Shani Taragin connects David HaMelech, Avraham Avinu and Yom Yerushalayim PAGE 7 Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks shares his passion for Jerusalem PAGE 18 Dr. Yael Ziegler with some fascinating insights into the Book of Ruth PAGE 14 Rabbi Hershel Schachter explains how we determine the date of Shavuot PAGE 8 Sivan Rahav Meir INSIDE! and Yedidya Meir offer some inspiring A special Aseret HaDibrot section, with 10 refreshing thoughts thoughts for these a fun Jerusalem Quiz for all the family times and a delicious Israeli cheesecake recipe! PAGE 30 our fallen heroes לעילוי נשמות sponsored anonymously www.mizrachi.org [email protected] +972 (0)2 620 9000 CHAIRMAN Mr. Harvey Blitz CHIEF EXECUTIVE Rabbi Doron Perez EDUCATIONAL DIRECTORS Rabbi Reuven Taragin Rabbanit Shani Taragin PUBLISHED BY THE MIZRACHI WORLD MOVEMENT EDITORIAL TEAM Daniel Verbov Esther Shafier CREATIVE DIRECTOR חג שמח Jonny Lipczer DESIGN SUPPORT Elisheva Mostovicz PRODUCTION AND ADVERTISING MANAGER chag sameach Meyer Sterman [email protected] from all of us HaMizrachi seeks to spread Torat Eretz Yisrael throughout the world. HaMizrachi also contains articles, opinion pieces and advertisements that represent the diversity of views and at mizrachi interests in our communities. These do not necessarily reflect any official position of Mizrachi or its branches. -

October Layout 1

AMERICAN & INTERNATIONAL SOCIETIES FOR YAD VASHEM Vol. 43-No. 1 ISSN 0892-1571 September/October 2016-Tishri/Cheshvan 5777 LEADERSHIP MISSION VISITS POLAND AND ISRAEL er, eager to share the special experi- presence of the third generation was life for centuries. BY ISAAC BENJAMIN ence together. a strong influence on the entire group. Outside of Wroclaw was the Sixteen young adults represented “Seeing all the young people on this Wolfsberg forced labor camp. Built as n the summer of 2015, supporters the American Society’s Young trip has been an inspiration. Their a series of tunnels underneath a small from the American Society for Yad I Leadership Associates as the third vitality and enthusiasm all along the mountain, it was where thousands of Vashem first began discussing a Jewish prisoners were forced into prospective mission to Poland and hard labor. As the group walked Israel. Understanding its unique sta- through the damp tunnels, Yad tus as the world’s preeminent Vashem guides recounted the story of Holocaust institution, the American Naphtali Stern, a prisoner at Society considered such a trip an Wolfsberg. Trading his rations for a exceptional opportunity to reflect on pencil stub, Stern wrote the Rosh the importance of Holocaust remem- Hashanah service from memory onto brance in the 21st century. A little scraps torn from bags of cement. more than a year later, the 31 Stern survived the Holocaust and Americans on the Leadership Mission later in life donated his cherished joined their international partners in prayer book to Yad Vashem. Later on, this unforgettable profound testament each participant received a replica of to Yad Vashem’s crucial role as the the “Wolfsberg Machzor,” its tattered World Holocaust Remembrance edges a reminder of the unimaginable Center. -

Salvage to Restitution: „Heirless‟ Jewish Cultural Property in Post-World War II

Salvage to Restitution: „Heirless‟ Jewish Cultural Property in Post-World War II Shir Kochavi Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds, School of Fine Art, History of Art and Cultural Studies May, 2017 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. ©2017 The University of Leeds and Shir Kochavi The right of Shir Kochavi to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by Shir Kochavi in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Table of Content Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………....5 Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………..7 List of Abbreviations…………………………………………………………………………..8 Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………...9 Chapter 1: Mordecai Narkiss and the Bezalel Museum……………………………………...34 - Bezalel Before Narkiss 1906-1920…………………………………………………...37 - The Bezalel Museum Collection…………………………………………………..…44 - Bezalel and Narkiss 1920-1932………………………………………………………53 - Bezalel After Schatz 1932-1942……………………………………………………...67 - Finding A Jewish Art………………………………………………………………...76 - The Schatz Fund for the Salvage of Jewish Art Remnants…………………………..82 Chapter 2: Point of Collecting………………………………………………………………104 - The CCPs and the Question of the Rightful Heirs………………………………….109 - Cultural Property for Disposition.…………………………………………………..120 - „Heirless‟ “General” Art……………………………………………………………134 - A Call to Continue the Salvage……………………………………………………..143 Chapter 3: The Jewish Museum as Recipient of the „Heirless‟ Jewish Cultural Property….159 - Development of the Jewish Museum……………………………………………….165 - Planning a New Jewish Museum.…………………………………………….…….175 - Working with the JCR………………………………………………………………187 - A Controversial Disposition………………………………………………………...191 - Harry G.