Transformations in the Canadian Youth Justice System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hon. Stanley H. Knowles Fonds MG 32, C 59

LIBRARY AND BIBLIOTHÈQUE ET ARCHIVES CANADA ARCHIVES CANADA Canadian Archives and Direction des archives Special Collections Branch canadiennes et collections spéciales Hon. Stanley H. Knowles fonds MG 32, C 59 Finding Aid No. 1611 / Instrument de recherche no 1611 Prepared by Colleen Dempsey and David Préparé par Colleen Dempsey et David Ross. Ross. Revised in 1991 by Geoff Ott for the Révisé en 1991 par Geoff Ott pour le service Political Archives Service. des archives politiques. -ii- TABLE OF CONTENTS Pages Index Headings .............................................................. ii Guide to the Finding Aid ...................................................... .xii Political Series vols. 1-349 ......................................................... 1-256 vols. 398-402 ..................................................... 293-295 vols. 412-485 ..................................................... 300-359 vols. 488-494 ..................................................... 361-366 vols. 502-513 ......................................................... 371 Canadian Labour Congress vols. 350-389 ..................................................... 256-288 vol. 513 ............................................................. 380 Personal Series vols. 390-397 ..................................................... 288-293 vols. 403-411 ..................................................... 295-300 vols. 486-487 ..................................................... 359-361 vols. 495-502 .................................................... -

Archived Content Contenu Archivé

ARCHIVED - Archiving Content ARCHIVÉE - Contenu archivé Archived Content Contenu archivé Information identified as archived is provided for L’information dont il est indiqué qu’elle est archivée reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It est fournie à des fins de référence, de recherche is not subject to the Government of Canada Web ou de tenue de documents. Elle n’est pas Standards and has not been altered or updated assujettie aux normes Web du gouvernement du since it was archived. Please contact us to request Canada et elle n’a pas été modifiée ou mise à jour a format other than those available. depuis son archivage. Pour obtenir cette information dans un autre format, veuillez communiquer avec nous. This document is archival in nature and is intended Le présent document a une valeur archivistique et for those who wish to consult archival documents fait partie des documents d’archives rendus made available from the collection of Public Safety disponibles par Sécurité publique Canada à ceux Canada. qui souhaitent consulter ces documents issus de sa collection. Some of these documents are available in only one official language. Translation, to be provided Certains de ces documents ne sont disponibles by Public Safety Canada, is available upon que dans une langue officielle. Sécurité publique request. Canada fournira une traduction sur demande. HISTORY OF THE LAW FOR JUVENILE DELINQUENTS No. 1984-56 Ministry of the Solicitor General of Canada Secretariat Copyright of this document does not belong to the Cffln. Proper authorization must be obtained from the author fa any intended use. Les droits d'auteur du présent document n'appartiennent pas à i'État. -

SASE Lesson Plan Template

U.S. Juvenile Justice System: From Playgrounds to Prison Dominique-Faith Worthington [email protected] EDFD 449- Human Rights, Holocaust, and Genocide Education Dept. Dr. Burkholder May 13, 2019 Date of Lesson: April 30, 2019 Lesson duration: 40min (with optional 60 min) Topic of Lesson: US Juvenile Justice System: From Play Grounds to Prison Central Focus: The student will understand how and why a juvenile becomes incarcerated into the system. Discussion will connect two local cases. The student then will apply critical thought through provided lesson material and identify what role the individual student plays in changing the current system or maintaining the status quota? Posing the final thought, “What does the ideal system look like?” Essential Question(s): Why do youths become incarcerated? What is the difference between adult and youth incarceration? What are the successes and failures of the juvenile justice system? How or why can a student reform the system? What would the ideal system look like? State/Disciplinary Standards: https://www.state.nj.us/education/cccs/2014/ss/ Standard 6.1 U.S. History: America in the World Standard 6.3 Active Citizenship in the 21st Century Daily Performance Objectives: Include student outcomes both as Understandings (i.e. “Big Ideas”), as well as unit-driven Knowledge and Skills. The student will critically think about self-accountability of their own behavior in society, in addition to individual reflection on their impacting abilities to changing the current system. Prior Knowledge Resources: List links to previous lessons, student ideas or misconceptions you anticipate, and describe any resources (including cognitive, cultural, experiential, etc.) that students may possibly bring to this lesson Civil rights movement (past lesson close to subject matter), juvenile delinquent perceptions, correction officer’s perceptions, lack of awareness of local cases, and lack of understanding of political complication and bureaucracies. -

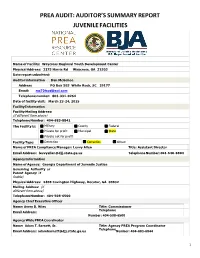

Prea Audit: Auditor’S Summary Report Juvenile Facilities

PREA AUDIT: AUDITOR’S SUMMARY REPORT JUVENILE FACILITIES Name of Facility: Waycross Regional Youth Development Center Physical Address: 3275 Harris Rd Waycross, GA 31503 Date report submitted: Auditor information Dan McGehee Address PO Box 595 White Rock, SC 29177 Email: [email protected] Telephone number: 803-331-0264 Date of facility visit: March 23-24, 2015 Facility Information Facility Mailing Address: (if different from above) Telephone Number: 404-683-8841 The Facility is: Military County Federal Private for profit Municipal State Private not for profit Facility Type: Detention Correction Other: Name of PREA Compliance Manager: Levvy Allen Title: Assistant Director Email Address: [email protected] Telephone Number:404-640-8804 Agency Information Name of Agency: Georgia Department of Juvenile Justice Governing Authority or Parent Agency: if licable) Physical Address: 3408 Covington Highway, Decatur, GA 30032 Mailing Address: (if different from above) Telephone Number: 404-508-6500 Agency Chief Executive Officer Name: Avery D. Niles Title: Commissioner Telephone Email Address: Number: 404-508-6500 Agency Wide PREA Coordinator Name: Adam T. Barnett, Sr. Title: Agency PREA Program Coordinator Telephone Email Address: [email protected] Number: 404-683-6844 1 AUDIT FINDINGS PROGRAM DESCRIPTION AND FACILITY CHARACTERISTICS: The Waycross Regional Youth Detention Center (RYDC), Georgia Department of Juvenile Justice, is a 30 bed facility that provides temporary, secure care and supervision to youth who are charged with crimes or who have been found guilty of crimes and are awaiting disposition of their cases by a juvenile court. The facility is a secure facility of brick and block construction built in 1966. -

Detention Center to Home School: the Path of Transition

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2015 Detention Center to Home School: The Path of Transition Sarah Hogeveen Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Hogeveen, Sarah, "Detention Center to Home School: The Path of Transition" (2015). Dissertations. 1267. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/1267 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2015 Sarah Hogeveen LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO DETENTION CENTER TO HOME SCHOOL: THE PATH OF TRANSITION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF EDUCATION IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF EDUCATION PROGRAM FOR ADMINISTRATION AND SUPERVISION BY SARAH HOGEVEEN CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MAY 2015 Copyright by Sarah Hogeveen, 2015 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The successful completion of this study was only possible because of the support of a variety of people. I would like to take this time to thank all of those people who offered support, time, and guidance as I completed this process. To my husband, Nick, and my daughters, Madison and Morgan, who have stood by my side during this process and supported me one hundred percent, I love you so very much. To my parents, Sue and Greg, your belief in me never faltered and it kept me going. -

A Legislative Framework for Abolition of Juvenile Pretrial Detention

Reviving the Presumption of Youth Innocence Through a Presumption of Release: A Legislative Framework for Abolition of Juvenile Pretrial Detention Sara S. Hildebrand* ABSTRACT Juvenile courts were established at the beginning of the twentieth century by a group of reformers who called themselves “Child Savers.” Those founders believed that fundamental differences between adults and children—such as children’s developmental immaturity and malleability—required the establishment of a court for youth, separate from adult criminal court, that focused on youth rehabilitation. Over time, the focus in most juvenile courts has shifted away from rehabilitation towards retribution, punishment, and protection of public safety—principle aims of the adult criminal system. These policy changes have facilitated an exponential increase in the number of youths detained during the pretrial period of their cases in juvenile court. In 2018, over 195,000 presumptively innocent youth were detained between arrest and final disposition of their juvenile delinquency case. Troublingly, the procedures designed to ensure objectivity and fairness in pretrial detention decision-making instead invite subjective judgments and result in disproportionate pretrial detentions of youth of color. Moreover, an earnest assessment of peer-reviewed studies reveals that pretrial detention of youth fails to serve its intended objectives of protecting the safety of high-risk youth and ensuring their appearance in court. While in pretrial detention, youth often do not get the educational or mental-health support they need and are frequently exposed to * Clinical Teaching Fellow, University of Denver, Sturm College of Law. J.D., University of Denver, Sturm College of Law. Thanks to Profs. Nicole Godfrey, Tammy Kuennen, Christopher N. -

Road Map to to Zero Youth Detention

Road map to ĞƌŽzŽƵƚŚĞƚĞŶƟŽŶ Identify and Prevent youth from eliminate policies Invest in the Lead with entering the juvenile racial equity that result in racial workforce disproportionality legal system Support community based Provide access to high Support development response to youth and quality, community based of restorative policies families in crisis so that services for communities, and practices to keep legal system involvement is youth, and families youth engaged in rare and the last resort school Divert youth from the Divert youth from Divert youth from Divert youth formal legal process and law enforcement referral, case filing, and from secure detention to community arrest and/or detention based options citation adjudication Ensure arrested and Expand family Reengage Support youth and families detained youth receive support and youth from to reduce recurrence of trauma-informed, culturally engagement detention into legal system outcomes and responsive, developmentally opportunities and community improve health outcomes appropriate care connections Align and optimize Utilize data and Support policy reform Align systems through that improves the lives of connections between technology to optimize partnership, common connections between youth, children, and systems to increase goals, outcomes and legal, community, and families and reduces effectiveness indicators services systems legal system involvement Table of Contents ϭ džĞĐƵƟǀĞ^ƵŵŵĂƌLJ ϳ /ŶƚƌŽĚƵĐƟŽŶ ϴ ĐŬŶŽǁůĞĚŐĞŵĞŶƚƐ ϵ tŚLJƚŚĞZŽĂĚDĂƉŝƐEĞĐĞƐƐĂƌLJ ϵ ĞƩĞƌKƵƚĐŽŵĞƐĨŽƌzŽƵƚŚĂŶĚ^ĂĨĞƌŽŵŵƵŶŝƟĞƐ -

The Youth Criminal Justice System 327 Looking Back Youth Criminal Legislation: a Brief History

The Youth Criminal 1100 Justice System What You Should Know Selected Key Terms • How do the Juvenile Delinquents alternative measures presumptive offence Act, the Young Offenders Act, and program young offender the Youth Criminal Justice Act extrajudicial measure differ? How are they similar? Young Offenders Act (YOA) foster home • How are young people treated youth criminal differently from adults when group home Youth Criminal Justice Act they break the law? juvenile delinquent (YCJA) • What options are available to the police in dealing with PoliceP report that rate of youths charged young non-violent, fi rst-time offenders? with criminal offences declines 26% • What are a youth criminal’s legal rights? • What options are available Teen gets 10 years to judges in sentencing youth criminals? Fewer • When is custody an for killing family appropriate sentence for a youth criminal? youth in court Chapter at a Glance and in 10.1 Introduction YOUTH HOMICIDES UP 10.2 The Youth Criminal Justice Act custody 10.3 Legal Rights of Youths 3 PERCENT IN 2006 10.4 Trial Procedures school over a cecellphone 10.5 Youth Sentencing Options Grade 11 teen stabbedbb d att school over a cellphone Violent crimes committed by youth receive increased media attention, as refl ected in these headlines. 332626 Unit 2 Criminal Law NEL 10.1 Introduction Activity Youth crime is a hot topic in Canada, and just about everybody has an To learn more about opinion on it. The headlines on page 326 present confl icting views on youth youth crime statistics, crime. Most suggest youth crime is on the rise, yet Statistics Canada recently Go to Nelson released fi gures that provide a different picture. -

Juvenile Justice in the Gaza Strip

Al Mezan Center for Human Rights Fact Sheet Juvenile Justice in the Gaza Strip 2012 to 2016 2016 Introduction It goes without saying that present-day youth are the adults of the future. It follows that, if a minor who comes into contact with the law is not effectively rehabilitated, he or she is faced with the prospect of an adulthood of crime. From this rationale develops the understanding that establishing a holistic, comprehensive juvenile justice system is a fundamental safeguard in the respect, protection, and promotion of human rights, and is a critical factor in building a crime-free society. International legal protections for children related to juvenile justice are contained primarily in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). The CRC outlines minimum protections and guarantees for children and articulates international human rights norms and principles that specifically apply to children. The juvenile justice “Beijing Rules” contain the UN’s standard minimum rules for the administration of juvenile justice. Together, the child’s best interests principle and imprisonment only as a last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time form the basis of obligations for duty bearers concerned with juvenile justice. It follows that all minors are entitled to a fair and public hearing by a competent, independent, and impartial tribunal. Also, that torture and ill-treatment are absolutely prohibited without exception. These obligations grant juvenile offenders rights that are vital for their legal protection,1 rehabilitation, and reintegration into society, by detailing procedures that must be followed for the care and trial of juvenile offenders. -

Canadian Law 10

Canadian Law 10 The Youth Criminal 90 Justice System Terms—Old & New • A youth criminal is a person who is 12–17 years old and is charged with an offence under the current Youth Criminal Justice Act (YCJA). • A young offender was a person aged 12–17 who was charged with an offence under the previous Young Offenders 90 Act (YOA). • A juvenile delinquent was a young person from the age of 7 or older who was charged as a young offender or youth criminal under the historic Juvenile Delinquents Act (JDA). Canadian Law 40S R. Schroeder 2 Juvenile Delinquents Act • Until the 1890s, there was no distinction between how adults and youth were treated by the law. • In 1892, the Criminal Code was amended to try children separately from adults. • In 1908, the federal government passed the Juvenile Delinquents 90 Act (JDA). • The age limit under the JDA ranged from 7 to 16 or 18 years old (depending on the province). • Youth who committed crimes were treated as “delinquents,” not criminals; focus was to rehabilitate, not punish them. • Legal rights of juveniles were mostly ignored and as a result their sentences were often unfair and inconsistent. Canadian Law 40S R. Schroeder 3 Young Offenders Act • The Young Offenders Act (YOA) officially replaced the JDA in 1984. • The minimum age changed from 7 to 12 and the maximum age was set at 17 in every province and territory. • The YOA recognized 90 the rights of youth as guaranteed in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. • Common criticisms of the YOA included: – being too soft on young offenders – not properly addressing serious and violent offences – lacking a clear philosophy on youth justice Canadian Law 40S R. -

New Mexico Juvenile Justice Services Fiscal Year 2018

New Mexico Juvenile Justice Services Fiscal Year 2018 1 This page left intentionally blank 2 State of New Mexico CHILDREN, YOUTH and FAMILIES DEPARTMENT MICHELLE-LUJAN GRISHAM BRIAN BLALOCK GOVERNOR CABINET SECRETARY HOWIE MORALES LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR Juvenile Justice Services (JJS) Annual Report Fiscal Year 2018 (July 1, 2017 to June 30, 2018) Tamera Marcantel, Deputy Director of Facility Services Nick Costales, Deputy Director of Field Services Dr. Jeffrey Toliver, Chief, FACTS Data Bureau Produced by: Data and Epidemiology Units Dr. Jackson Williams, LPCC, Data Analysis Unit Manager Kelly Maestas, Data Analyst Lori Zigich, Epidemiologist Special thanks to the Applications Analysis Unit (AAU). Their work has led to signifi- cant reductions in missing/unknown data points and improved the quality and relia- bility of FACTS, SARA, and ADE data: Amanda Trujillo, Program Manager Roman Montano, Management Analyst Supervisor Shannon Guericke, Operations Research Analyst Jen Parkins, Operations Research Analyst Sonia Jones, Management Analyst Alyssa Madden, Management Analyst Comments/suggestions regarding this publication may be emailed to: [email protected] 3 Table of Contents Introduction 8 CYFD mission statement………………………………………………………………..……..………………….....….…………………….…………..... 8 Map of Juvenile Justice Services facilities and centers………………………………………..……..…………………………….……….…. 8 Section 1. New Mexico Juvenile Population 9 Figure 1-1: Juvenile population, 2000-2017……………………………………..…..…………..….…………..………………….…………….. 9 Figure 1-2: Juvenile population, percent by gender, 2017……...…………………………..…………...….………...……………..…….. 9 Figure 1-3: Juvenile population, number by age and gender, 2017….……………………….………..…………………...………..….10 Figure 1-5: Juvenile population, percent by race/ethnicity, 2017………………..…………………...…………………….…………....10 Section 2. Total Referral Pathway and Outcomes 11 Figure 2-1: Youth referral pathway………………………………………………………………………...….……….………..……...…...….… ... 11 Figure 2-2: Outcomes for juvenile referrals/arrests (Tree Stats)..……..…………………….………..….…….………....…….…... -

Download Download

“Delinquents Often Become Criminals”: Juvenile Delinquency in Halifax, 1918-1935 MICHAEL BOUDREAU Au début du 20e siècle, la délinquance juvénile à Halifax était perçue comme un sérieux problème social et moral qu’il fallait résoudre sans tarder. Par conséquent, entre 1918 et 1935, de nombreux représentants de la justice pénale de Halifax endossèrent pleinement la plupart des facettes du système judiciaire moderne du Canada applicable aux jeunes afin de prendre des mesures contre les jeunes délinquants de l’endroit. En faisant appel à ce nouveau régime de réglementation (notamment le tribunal de la jeunesse et le système de probation des jeunes) pour lutter contre la délinquance juvénile, Halifax était à l’avant-plan, aux côtés d’autres villes, des efforts visant à réglementer et à criminaliser la vie d’enfants essentiellement pauvres et issus des milieux ouvriers, ainsi que de leurs familles. During the early part of the 20th century, juvenile delinquency in Halifax was perceived to be a serious social and moral problem that had to be solved without delay. Consequently, between 1918 and 1935, many of Halifax’s criminal justice officials fully embraced most facets of Canada’s modern juvenile justice system in order to deal with the local juvenile delinquents. By utilizing this new regulatory regime (notably the juvenile court and probation) to grapple with juvenile delinquency, Halifax was in the forefront, along with other cities, of the efforts to regulate and criminalize the lives of primarily poor, working-class children and their families. THE CENTRAL GARAGE ON GRAFTON STREET in downtown Halifax had been the site of two thefts in the spring of 1923.