Georgia's Signers of the Declaration of Independence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Descendants of James Mathews Sr

Descendants of James Mathews Sr. Greg Matthews Table of Contents .Descendants . .of . .James . .Mathews . .Sr. 1. .First . Generation. 1. .Source . .Citations . 2. .Second . Generation. 3. .Source . .Citations . 9. .Third . Generation. 15. .Source . .Citations . 32. .Fourth . Generation. 47. .Source . .Citations . 88. .Fifth . Generation. 115. .Source . .Citations . 147. .Sixth . Generation. 169. .Source . .Citations . 192. Produced by Legacy Descendants of James Mathews Sr. First Generation 1. James Mathews Sr. {M},1 son of James Mathews and Unknown, was born about 1680 in Surry County, VA and died before Mar 1762 in Halifax County, NC. Noted events in his life were: • First appearance: First known record for James is as a minor in the Court Order Books, 4 Jun 1688, Charles City County, Virginia.2 Record mentions James and brother Thomas Charles Matthews and that both were minors. Record also mentions their unnamed mother and her husband Richard Mane. • Militia Service: Was rank soldier on 1701/2 Charles City County militia roll, 1702, Charles City County, Virginia.3 • Tax List: Appears on 1704 Prince George County Quit Rent Roll, 1704, Prince George County, Virginia.4 • Deed: First known deed for James Mathews Sr, 28 Apr 1708, Surry County, VA.5 On 28 Apr 1708 James Mathews and wife Jeane sold 100 acres of land to Timothy Rives of Prince George County. The land was bound by Freemans Branch and John Mitchell. Witnesses to the deed were William Rives and Robert Blight. • Deed: First land transaction in North Carolina, 7 May 1742, Edgecombe County, NC.6 Was granted 400 acres in North Carolina by the British Crown in the first known deed for James in NC. -

Study Guide for the Georgia History Exemption Exam Below Are 99 Entries in the New Georgia Encyclopedia (Available At

Study guide for the Georgia History exemption exam Below are 99 entries in the New Georgia Encyclopedia (available at www.georgiaencyclopedia.org. Students who become familiar with these entries should be able to pass the Georgia history exam: 1. Georgia History: Overview 2. Mississippian Period: Overview 3. Hernando de Soto in Georgia 4. Spanish Missions 5. James Oglethorpe (1696-1785) 6. Yamacraw Indians 7. Malcontents 8. Tomochichi (ca. 1644-1739) 9. Royal Georgia, 1752-1776 10. Battle of Bloody Marsh 11. James Wright (1716-1785) 12. Salzburgers 13. Rice 14. Revolutionary War in Georgia 15. Button Gwinnett (1735-1777) 16. Lachlan McIntosh (1727-1806) 17. Mary Musgrove (ca. 1700-ca. 1763) 18. Yazoo Land Fraud 19. Major Ridge (ca. 1771-1839) 20. Eli Whitney in Georgia 21. Nancy Hart (ca. 1735-1830) 22. Slavery in Revolutionary Georgia 23. War of 1812 and Georgia 24. Cherokee Removal 25. Gold Rush 26. Cotton 27. William Harris Crawford (1772-1834) 28. John Ross (1790-1866) 29. Wilson Lumpkin (1783-1870) 30. Sequoyah (ca. 1770-ca. 1840) 31. Howell Cobb (1815-1868) 32. Robert Toombs (1810-1885) 33. Alexander Stephens (1812-1883) 34. Crawford Long (1815-1878) 35. William and Ellen Craft (1824-1900; 1826-1891) 36. Mark Anthony Cooper (1800-1885) 37. Roswell King (1765-1844) 38. Land Lottery System 39. Cherokee Removal 40. Worcester v. Georgia (1832) 41. Georgia in 1860 42. Georgia and the Sectional Crisis 43. Battle of Kennesaw Mountain 44. Sherman's March to the Sea 45. Deportation of Roswell Mill Women 46. Atlanta Campaign 47. Unionists 48. Joseph E. -

Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide

Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide Guide to the educational resources available on the GHS website Theme driven guide to: Online exhibits Biographical Materials Primary sources Classroom activities Today in Georgia History Episodes New Georgia Encyclopedia Articles Archival Collections Historical Markers Updated: July 2014 Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide Table of Contents Pre-Colonial Native American Cultures 1 Early European Exploration 2-3 Colonial Establishing the Colony 3-4 Trustee Georgia 5-6 Royal Georgia 7-8 Revolutionary Georgia and the American Revolution 8-10 Early Republic 10-12 Expansion and Conflict in Georgia Creek and Cherokee Removal 12-13 Technology, Agriculture, & Expansion of Slavery 14-15 Civil War, Reconstruction, and the New South Secession 15-16 Civil War 17-19 Reconstruction 19-21 New South 21-23 Rise of Modern Georgia Great Depression and the New Deal 23-24 Culture, Society, and Politics 25-26 Global Conflict World War One 26-27 World War Two 27-28 Modern Georgia Modern Civil Rights Movement 28-30 Post-World War Two Georgia 31-32 Georgia Since 1970 33-34 Pre-Colonial Chapter by Chapter Primary Sources Chapter 2 The First Peoples of Georgia Pages from the rare book Etowah Papers: Exploration of the Etowah site in Georgia. Includes images of the site and artifacts found at the site. Native American Cultures Opening America’s Archives Primary Sources Set 1 (Early Georgia) SS8H1— The development of Native American cultures and the impact of European exploration and settlement on the Native American cultures in Georgia. Illustration based on French descriptions of Florida Na- tive Americans. -

Signers of the United States Declaration of Independence Table of Contents

SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE 56 Men Who Risked It All Life, Family, Fortune, Health, Future Compiled by Bob Hampton First Edition - 2014 1 SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTON Page Table of Contents………………………………………………………………...………………2 Overview………………………………………………………………………………...………..5 Painting by John Trumbull……………………………………………………………………...7 Summary of Aftermath……………………………………………….………………...……….8 Independence Day Quiz…………………………………………………….……...………...…11 NEW HAMPSHIRE Josiah Bartlett………………………………………………………………………………..…12 William Whipple..........................................................................................................................15 Matthew Thornton……………………………………………………………………...…........18 MASSACHUSETTS Samuel Adams………………………………………………………………………………..…21 John Adams………………………………………………………………………………..……25 John Hancock………………………………………………………………………………..….29 Robert Treat Paine………………………………………………………………………….….32 Elbridge Gerry……………………………………………………………………....…….……35 RHODE ISLAND Stephen Hopkins………………………………………………………………………….…….38 William Ellery……………………………………………………………………………….….41 CONNECTICUT Roger Sherman…………………………………………………………………………..……...45 Samuel Huntington…………………………………………………………………….……….48 William Williams……………………………………………………………………………….51 Oliver Wolcott…………………………………………………………………………….…….54 NEW YORK William Floyd………………………………………………………………………….………..57 Philip Livingston…………………………………………………………………………….….60 Francis Lewis…………………………………………………………………………....…..…..64 Lewis Morris………………………………………………………………………………….…67 -

Inventory of the Grimke Family Papers, 1678-1977, Circa 1990S

Inventory of the Grimke Family Papers, 1678-1977, circa 1990s Addlestone Library, Special Collections College of Charleston 66 George Street Charleston, SC 29424 USA http://archives.library.cofc.edu Phone: (843) 953-8016 | Fax: (843) 953-6319 Table of Contents Descriptive Summary................................................................................................................ 3 Biographical and Historical Note...............................................................................................3 Collection Overview...................................................................................................................4 Restrictions................................................................................................................................ 5 Search Terms............................................................................................................................6 Related Material........................................................................................................................ 6 Administrative Information......................................................................................................... 7 Detailed Description of the Collection.......................................................................................8 John Paul Grimke letters (generation 1)........................................................................... 8 John F. and Mary Grimke correspondence (generation 2)................................................8 -

Bloody, Bloody Yazoo Jackson

P a g e | 1 Andrew Edwards Mae Ngai/Elizabeth Blackmar Senior Thesis Word Count: 20,121 4.4.2011 Bloody, Bloody Yazoo Jackson The Crisis over Speculation and Sovereignty in the Early Republic P a g e | 2 “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.” ~The Tenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1791. In the broadest sense, political struggles between republicans and federalists in the earliest years of the American republic were about a trade-off between freedom and power. According to early Chief Justice John Marshall republicans resisted ―every attempt to transfer from their own hands into those of congress powers which by others,‖ Marshall‘s federalists, ―were deemed essential to the preservation of the union.‖1 Conversely, as republican newspaper editor and poet Philip Freneau wrote in 1793, ―the people rejoice in their freedom, and are determined to maintain it.‖2 Yet those two concepts, freedom and power, so familiar from history and manifest in the political discourse of George Washington and John Adams‘s administrations, remain opaque. The antagonisms of freedom and power are so broadly understood that contradictory interpretations can be made from the same evidence. Charles Beard interpreted the political divide of the 1790s as ―a profound division‖ that ―ensued throughout the United States based on different views of the rights of property,‖ with capitalist federalists on one side and agrarian republicans on the other.3 As Joyce Appleby reinterpreted them, however, republicans were ―progressive,‖ ―capitalist,‖ ―new money‖ men, who had no patience for the aristocratic pretentions of the ―elites,‖ while ―elite‖ federalists were, perhaps, just better organized.4 For 1 Marshall quoted by Beard. -

In Memoriam 1992

Georgia Society Sons of the American Revolution A Tribute to Absent Compatriots 1921 - 2018 IN MEMORIAM 2018 A TRIBUTE TO ABSENT COMPATRIOTS The Georgia Society Sons of the American Revolution acknowledges with grateful appreciation the membership of the following Compatriots. Through the records of our organization they will always be associated with their Patriot ancestors. We give hearty thanks to both for the good examples that they made of their lives and for their faith in God and country. To their memories and to their families we hereby express the respect and appreciation of a grateful Society. IN MEMORIAM 2018 Compatriot Charles Hal Dayhuff Marquis de Lafayette 02 January 2018 Compatriot Albert Mims Wilkinson, Jr. Atlanta 14 January 2018 Compatriot Charles Alfred DeSaussure, III Lyman Hall 18 January 2018 Compatriot Franklin Lee Barron Wiregrass 21 January 2018 Compatriot Thomas Robert McEvoy Cherokee 14 Feb 2018 Compatriot Gregory Andrew Hollis Marshes of Glynn 02 March 2018 Compatriot James Alan Richardson William Few 10 March 2018 Compatriot Allan Arthur Malone Wiregrass 09 April 2018 Compatriot McLane Tilton, IV Marshes of Glynn 10 April 2018 Compatriot Fletcher Ryals Dunaway Joel Early 20 April 2018 Compatriot Dares Emery Wirt Atlanta 26 April 2018 Compatriot Clyde Thomas Adams Samuel Elbert 05 May 2018 2 Compatriot John Marshall Cordell Samuel Elbert 28 May 2018 Compatriot Thomas Parks Oliver, III Athens 14 June 2018 Compatriot Kenneth Clarence Reed, III Mount Vernon 17 June 2018 Compatriot Clarence Wells Jackson, Jr. Marquis de Lafayette 08 August 2018 Compatriot Lyle Edward Letteer, Jr. Lyman Hall 16 August 2018 Compatriot Curtis Eugene McWaters Captain John Collins 17 August 2018 Compatriot David Oscar Bell Marshes of Glynn 25 August 2018 Compatriot Thomas Augustus Carrere Casimir Pulaski 03 September 2018 Compatriot William Spurgeon Warr Coweta Falls 18 September 2018 Compatriot Charles Henry Jordan Fall Line 02 October 2018 Compatriot Edward Carney Hackney Marquis de Lafayette 04 November 2018 Compatriot Ralph Waldo Satterwhite, Jr. -

Atlanta Tidbits Ledger Atlanta Chapter Sons of the American Revolution Organized March 15, 1921 Volume 6 – Issue 4 Atlanta, Georgia April 2017

Atlanta Tidbits Ledger Atlanta Chapter Sons of the American Revolution Organized March 15, 1921 www.saratlanta.org Volume 6 – Issue 4 Atlanta, Georgia April 2017 Next Meeting – Thursday April 13th Mark your calendars for Thursday April 13th chapter meeting at the Petite Violette Restaurant, 2948 Clairmont Rd, Atlanta, GA 30329. Regular meetings are held on the second Thursdays of the month except in February when we meet on the Saturday closest to Washington’s birthday and in July and August when we do not schedule a regular meeting. Remember those soda can tabs, Labels for Education, and Box Tops for Education for donation to the Children of the American Revolution, magazines and toiletries for veterans at the VA Hospital, paperback books for the USO, and history and genealogy books for our fund raising Traveling Book Store. A drop-off point at the table next to the registration table is set up to receive your donations. Highlights of March Meeting The speaker for the March meeting was Robert C. Jones who discussed Georgia Heroes in the American Revolution. He talked about Elijah Clarke, Nancy Hart, Lachlan McIntosh, Archibald Bulloch, Lyman Hall, George Walton, Samuel Elbert Button Gwinnett and others. President Cobb presents a certificate of appreciation to speaker Jones. New Member William Michael “Mike” Prince was inducted as a new member at the March meeting. Please welcome Mike as a new member. President Henry Cobb, Mike Prince, Past President Terry Manning Membership The NSSAR Genealogist General reports that in 2016 the SAR received over 4,000 new applications with current approval time at 12 weeks after they are received at NSSAR. -

Fort Tonyn and the Campaign of 1778

Florida Historical Quarterly Volume 29 Number 4 Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol 29, Article 5 Issue 4 1950 Fort Tonyn and the Campaign of 1778 Ripley P. Bullen Part of the American Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Article is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Historical Quarterly by an authorized editor of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Bullen, Ripley P. (1950) "Fort Tonyn and the Campaign of 1778," Florida Historical Quarterly: Vol. 29 : No. 4 , Article 5. Available at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq/vol29/iss4/5 Bullen: Fort Tonyn and the Campaign of 1778 FORT TONYN AND THE CAMPAIGN OF 1778 By RIPLEY P. BULLEN Asst. Archeolo.qist, FLorida State Board of Parks awd Historic Memorials Fort Tonyn, a small British fort during the American Revolution, is ‘believed by some to have been located on Amelia Island at the site now occupied by Fort Clinch. The probable reason for this tradition is the fact that it is so located on a map prepared by-W. 0. F. Wallace, Esq., and included by Burton Barrs in his East Florida iru the Americavt Revolu;tios.l No substantiating evidence for this location is given by Barrs and it may be stated cate- gorically that Wallace’s map is incorrect in this respect. Named for the last British governor of East Florida, Fort Tonyn was, apparently, never recognized as a fort by the British. -

Arthur Joseph Funk Papers

Arthur Joseph Funk papers Descriptive Summary Repository: Georgia Historical Society Creator: Funk, Arthur Joseph, 1898-1975. Title: Arthur Joseph Funk papers Dates: 1903-1975 Extent: 2.55 cubic feet (5 boxes, 8 oversize folders) Identification: MS 1304 Biographical/Historical Note Arthur Joseph Funk (1898-1975), educator and politician was born in Savannah, the son of Sebastian Funk (d. 1925) and Jane (Wilson) Funk (1868-1937). Mr. Funk taught at Savannah High School (1920-1938), and was the principal of Commercial High School (1939-1953). In 1960 he was elected to the Georgia House of Representatives where, until his retirement in 1970, he fought against needless spending of tax money. Alongside these careers, Mr. Funk's pursued a long term interest in radio technology, Georgia history, and camellia culture. Scope and Content Note This collection consists of his papers spanning his lifetime. There are few that relate to his family, but rather most relate to his careers in education and politics. Included are correspondence, personal research notes, newspaper clippings, and original printed programs and documents relating to both education and politics. Of special interest are his papers regarding the search and verification of Button Gwinnett's grave. Also included are Mr. Funk's original commissions to the Georgia General Assembly and the 1953 edition of the Ship of Commerce, the Commercial High School yearbook that was dedicated to Mr. Funk. The collection also contains photographs, slides and x-rays spanning Mr. Funk's lifetime. There are several photographs of him as a child as well as those of him during his education and political careers. -

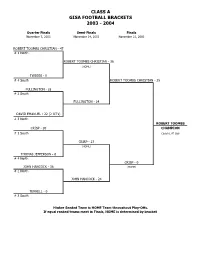

Class a Gisa Football Brackets 2003 - 2004

CLASS A GISA FOOTBALL BRACKETS 2003 - 2004 Quarter Finals Semi-Finals Finals November 7, 2003 November 14, 2003 November 21, 2003 ROBERT TOOMBS CHRISTIAN - 47 # 1 North ROBERT TOOMBS CHRISTIAN - 36 (HOME) TWIGGS - 0 # 4 South ROBERT TOOMBS CHRISTIAN - 35 FULLINGTON - 28 # 2 South FULLINGTON - 24 DAVID EMANUEL - 22 (2 OT's) # 3 North ROBERT TOOMBS CRISP - 20 CHAMPION # 1 South Coach L.M. Guy CRISP - 27 (HOME) THOMAS JEFFERSON - 6 # 4 North CRISP - 0 JOHN HANCOCK - 38 (HOME) # 2 North JOHN HANCOCK - 24 TERRELL - 0 # 3 South Higher Seeded Team is HOME Team throughout Play-Offs. If equal ranked teams meet in Finals, HOME is determined by bracket. 2003 GISA STATE FOOTBALL BRACKETS Friday, Nov. 7 AA BRIARWOOD - 21 Friday, Nov. 14 R1 # 1 Home is team with highest rank; when teams are (1) BRIARWOOD - 15 equally ranked, Home is as shown on brackets. (HOME) WESTWOOD - 0 Friday, Nov. 21 R3 # 4 (9) BRIARWOOD - 14 MONROE - 0 R4 # 2 (2) BULLOCH - 0 BULLOCH - 35 R2 # 3 Friday, Nov. 28 TRINITY CHRISTIAN - 47 R2 # 1 SOUTHWEST GA - 25 (3) TRINITY CHRISTIAN - 17 (13) (Home) (HOME) GATEWOOD - 6 R4 # 4 (10) TRINITY CHRISTIAN - 14 (HOME) BROOKWOOD - 6 R3 # 2 (4) BROOKWOOD - 14 EDMUND BURKE - 14 (15) BRENTWOOD R1 # 3 AA CHAMPS Coach Bert Brown SOUTHWEST GEORGIA - 51 R3 # 1 BRENTWOOD - 52 (5) SOUTHWEST GA - 44 (14) (HOME) CURTIS BAPTIST - 14 R1 # 4 (11) SOUTHWEST GA - 27 TIFTAREA - 42 (HOME) R2 # 2 (6) TIFTAREA - 14 PIEDMONT - 16 R4 # 3 FLINT RIVER - 27 R4 # 1 (7) FLINT RIVER - 21 (HOME) MEMORIAL DAY - 6 R2 # 4 (12) BRENTWOOD - 25 BRENTWOOD - 42 R1 # 2 (8) BRENTWOOD - 46 VALWOOD - 30 R3 # 3 2003 GISA STATE FOOTBALL BRACKETS Friday, Nov. -

Historic Augusta, Incorporated Collection of Revolutionary and Early Republic Era Manuscripts

Historic Augusta, Incorporated collection of Revolutionary and Early Republic Era manuscripts Descriptive Summary Repository: Georgia Historical Society Title: Historic Augusta, Incorporated collection of Revolutionary and Early Republic Era manuscripts Dates: 1770-1827 Extent: 0.25 cubic feet (19 folders) Identification: MS 1701 Biographical/Historical Note Historic Augusta, Incorporated was established in 1965 to preserve historic buildings and sites in Augusta and Richmond County, Georgia. Initially run by members of the Junior League, the organization is affiliated with the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Historic Augusta, Incorporated gives tours of the city, provides preservation assistance, advocacy, historic structures surveys, and sponsors various preservation programs. Scope and Content Note This collection contains approximately 19 manuscripts ranging from 1770 to 1827. These papers consist of land grants, legal documents, government appointments, letters concerning the military, a shipping ledger and permit, and a liquor license. The authors of these documents are some of Georgia’s early leaders: Benjamin Andrew – Delegate, Continental Congress, 1780 Samuel Elbert – Governor, 1785 John Habersham – Major - Continental Army; Delegate, Continental Congress, 1785 John Houstoun – Governor, 1778, 1784; First mayor of Savannah, 1790 Richard Howly – Governor, 1780; Delegate, Continental Congress, 1780, 1781 James Jackson – Governor, 1798-1800 George Mathews – Governor, 1787-88 Laughlin McIntosh – Major General - Continental Army; Delegate, Continental Congress, 1784 Nathaniel Pendleton – Major - Continental Army; Delegate, Continental Congress, 1789 Edward Telfair – Governor, 1789-93 John J. Zubly – First minister of Independent Presbyterian Church, Savannah (1760 - 1781); Delegate, Second Continental Congress, 1775 Index Terms Account books. Augusta (Ga.)--History--Revolution, 1775-1783. Clarke, Elijah, 1733-1799. Elbert, Samuel, 1740-1788.