Safety Guidelines for Implementing Chest Stands Into Dance And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Circus Friends Association Collection Finding Aid

Circus Friends Association Collection Finding Aid University of Sheffield - NFCA Contents Poster - 178R472 Business Records - 178H24 412 Maps, Plans and Charts - 178M16 413 Programmes - 178K43 414 Bibliographies and Catalogues - 178J9 564 Proclamations - 178S5 565 Handbills - 178T40 565 Obituaries, Births, Death and Marriage Certificates - 178Q6 585 Newspaper Cuttings and Scrapbooks - 178G21 585 Correspondence - 178F31 602 Photographs and Postcards - 178C108 604 Original Artwork - 178V11 608 Various - 178Z50 622 Monographs, Articles, Manuscripts and Research Material - 178B30633 Films - 178D13 640 Trade and Advertising Material - 178I22 649 Calendars and Almanacs - 178N5 655 1 Poster - 178R47 178R47.1 poster 30 November 1867 Birmingham, Saturday November 30th 1867, Monday 2 December and during the week Cattle and Dog Shows, Miss Adah Isaacs Menken, Paris & Back for £5, Mazeppa’s, equestrian act, Programme of Scenery and incidents, Sarah’s Young Man, Black type on off white background, Printed at the Theatre Royal Printing Office, Birmingham, 253mm x 753mm Circus Friends Association Collection 178R47.2 poster 1838 Madame Albertazzi, Mdlle. H. Elsler, Mr. Ducrow, Double stud of horses, Mr. Van Amburgh, animal trainer Grieve’s New Scenery, Charlemagne or the Fete of the Forest, Black type on off white backgound, W. Wright Printer, Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, 205mm x 335mm Circus Friends Association Collection 178R47.3 poster 19 October 1885 Berlin, Eln Mexikanermanöver, Mr. Charles Ducos, Horaz und Merkur, Mr. A. Wells, equestrian act, C. Godiewsky, clown, Borax, Mlle. Aguimoff, Das 3 fache Reck, gymnastics, Mlle. Anna Ducos, Damen-Jokey-Rennen, Kohinor, Mme. Bradbury, Adgar, 2 Black type on off white background with decorative border, Druck von H. G. -

Linguistic Variation of the American Circus

Abstract http://www.soa.ilstu.edu/anthropology/theses/burns/index.htm Through the "Front Door" to the "Backyard": Linguistic Variation of the American Circus Lisa Burns Illinois State University Anthropology Department Dr. James Stanlaw, Advisor May 1, 2003 Abstract The language of circus can be interpreted through two perspectives: the Traditional American Circus and the New American Circus. There is considerable anthropological importance and research within the study of spectacle and circus. However, there is a limited amount of academic literature pertaining to the linguistics and semiotics of circus. Through participant observation and interviewing, of both circus and non-circus individuals, data will be acquired and analyzed. Further research will provide background information of both types of circuses. Results indicate that an individual's preference can be determined based on the linguistic and semiotic terms used when describing the circus. Introduction Throughout my life, I have always been intrigued by the circus. As a result, I joined the Gamma Phi Circus, here at Illinois State University, in order to obtain a better understanding of circus in our culture. A brief explanation of the title is useful in understanding my paper. I chose the title "Through the 'Front Door' to the 'Backyard'" because "front door" is circus lingo for the doors that a person goes through on entering the tent. The word "backyard" refers to the area in which behind the tent where all the people in the production of the circus park their trailers. This title encompasses the range of information that I have gathered from performers, to directors, to audience members. -

Circuscape Workshops BOOKLET.Indd

CircusCape presents Fun Family Fridays, Payomet’s Circus Camp became an accredited summer camp last Super Saturdays, and more! year as a result of our high standards conforming to stringent The Art of Applying and state and local safety and operational requirements. Auditioning / Creating Our team of 5 professional Career Paths in Circus & instructors, lead by Marci Diamond, offers classes over Related Performing Arts 7-weeks for students, with Marci Diamond ages 7-14. Cost: $30 Every week will include aerial Fri 8/24 • 10-noon at Payomet Tent arts, acrobatics, juggling, mini-trampoline, physical comedy/ There are a wide range of career paths for the improv, puppeteering, object aspiring professional circus/performing artist, and manipulation, rope climbing and in this workshop, we will explore some possible physical training geared to the steps toward those dreams, as well as practical, interests and varying levels of individual students. effective approaches to applications and auditions. Applying and Auditioning for professional training programs (from short-term intensive workshops to 3 year professional training programs and universi- ty B.F.A. degrees) in circus and related performing arts, as well as for professional performance opportunities, can be a successful adventure of personal & professional growth, learning, and network-building. And it can be done with less stress than you may think! Come discuss tips for maximizing your opportunities while taking care of The core program runs yourself/your student/child. Practice your “asks and 4 days a week (Mon - Thurs) intros” with the director of the small youth circus from July 9 to August 23 at troupe, a professional circus performer and union the Payomet Tent. -

It's a Circus!

Life? It’s A Circus! Teacher Resource Pack (Primary) INTRODUCTION Unlike many other forms of entertainment, such as theatre, ballet, opera, vaudeville, movies and television, the history of circus history is not widely known. The most popular misconception is that modern circus dates back to Roman times. But the Roman “circus” was, in fact, the precursor of modern horse racing (the Circus Maximus was a racetrack). The only common denominator between Roman and modern circuses is the word circus which, in Latin as in English, means "circle". Circus has undergone something of a revival in recent decades, becoming a theatrical experience with spectacular costumes, elaborate lighting and soundtracks through the work of the companies such as Circus Oz and Cirque du Soleil. But the more traditional circus, touring between cities and regional areas, performing under the big top and providing a more prosaic experience for families, still continues. The acts featured in these, usually family-run, circuses are generally consistent from circus to circus, with acrobatics, balance, juggling and clowning being the central skillsets featured, along with horsemanship, trapeze and tightrope work. The circus that modern audiences know and love owes much of its popularity to film and literature, and the showmanship of circus entrepreneurs such as P.T. Barnum in the mid 1800s and bears little resemblance to its humble beginnings in the 18th century. These notes are designed to give you a concise resource to use with your class and to support their experience of seeing Life? It’s A Circus! CLASSROOM CONTENT AND CURRICULUM LINKS Essential Learnings: The Arts (Drama, Dance) Health and Physical Education (Personal Development) Style/Form: Circus Theatre Physical Theatre Mime Clowning Themes and Contexts: Examination of the circus style/form and performance techniques, adolescence, resilience, relationships General Capabilities: Personal and Social Competence, Critical and Creative Thinking, Ethical Behaviour © 2016 Deirdre Marshall for Homunculus Theatre Co. -

From Technical Movement to Artistic Gesture the Trampoline, Training Support for Propulsion

PEDAGOGICAL GUIDE FROM TECHNICAL MOVEMENT TO ARTISTIC GESTURE THE TRAMPOLINE, TRAINING SUPPORT FOR PROPULSION 01 TEACHING PROPULSION DISCIPLINES 1 02 A BRIEF SUMMARY OF THE INTENTS PROJECT 05 FOREWORD 07 INTRODUCTION 01 09 TEACHING PROPULSION DISCIPLINES MODALITIES AND TRANSFERS 11 A review of the trampoline’s place in the teaching of circus disciplines 15 Methodology of technical progression on the trampoline 19 The technical movement: mastery and safety 27 Transfers from one discipline to another 31 Observing the body moving through the air 02 39 FROM A SPORT TO AN ARTISTIC GESTURE WHEN LEARNING DISCIPLINES WITH PROPULSION 41 From an athletic to an artistic jump: questions of intent A detour by gesture analysis 47 Defining and developing an acrobatic presence 53 Artistic research on propulsion pieces of equipment From improvisation to staging 62 CONCLUSION 64 BIBLIOGRAPHY 66 ANNEXES TEACHING MANUAL FROM TECHNICAL MOVEMENT TO ARTISTIC GESTURE THE TRAMPOLINE, TRAINING SUPPORT FOR PROPULSION ASSOCIATED AUTHOR : AGATHE DUMONT Published by the Fédération Française des Écoles de Cirque and the European Federation of Professional Circus Schools 1 A brief summary of the INTENTS project The INTENTS project was born out of the necessity and desire to give structure to the professional circus arts training, to harmonise it, and to increase its professionalism and credibility; the INTENTS project specifically addresses the training of circus arts’ teachers. BACKGROUND A teachers’ consultation launched by FEDEC in 2011 The teachers’ continuing professional development is (SAVOIRS00) highlighted the lack of teaching tools and key to ensuring a richer and evolving training method common methodologies with regards to initial and continu- for their students. -

BRIO Youth Training Company (Ages 8-18) September 2020 - June 2021

BRIO Youth Training Company (ages 8-18) September 2020 - June 2021 1 Brio Program Overview About Brio The Brio Youth Training Company is a ten-month developmental program preparing young circus artists to pursue the joy and wonder of circus with greater intensity. Brio company members will have the opportunity to work with professional performers and world-class instructors to build skills and explore the limitless world of circus arts. Our overarching goal is to facilitate the development of circus skills, creativity, and professionalism, at an appropriate level for the development of our students within a program that is engaging, challenging, growth-oriented, and fun. The structure is designed to be clear— with three levels of intensity—yet flexible enough to respond to individuals’ needs. Candidates should have a background in movement disciplines such as dance, gymnastics, martial arts, parkour, diving, or ice skating, and a desire to bring their passion for the circus arts to the next level. Ideal Brio company members are ages 8 to 18 and interested in exploring the possibilities of circus arts; members may be looking forward towards next steps in our Elements adult training company or circus college, or may just be excited to work with a community of creative and dedicated young artists! The program is currently designed to adjust to the safest training environment, whether online only, hybrid online and small in-studio lessons, or full in-studio classes; see program details below for further information. Training Levels: Junior Core Training Program Students age 8-10 have the option of Brio Junior Core, an introductory program with a lower time commitment than the traditional Core training program. -

Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Wings

Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Wings 0000-01 2:30-3:45PM Pre-Professional Program 0000-01 2:00-3:30PM Open Gym 0000-01 2:30-4:00PM Pre-Professional Program 0000-01 2:00-3:30PM Cloud Swing 0000-01 3:00-3:30PM 9:00 AM Swinging Trapeze 1000-01 3:00-3:30PM Bite Balance 1000-01 3:15-4:00PM Duo Trapeze 1000-03 3:30-4:15PM Chair Stacking 0100-01 3:30-4:00PM Swinging Trapeze 1000-01 3:00-3:30PM Acrobatics 0105-02 ages 10+ 3:00 PM 3:00 Audition Preparation for Professional Circus Schools 0000-01 3:30-4:30PM Handstands 1000-01 Triangle Trapeze 0100-03 3:30-4:00PM Hammock 0300-01 3:30-4:00PM Flying Trapeze Recreational 0000-01 4-Girl Spinning Cube 0100-01 3:45-4:15PM Swinging Trapeze 0000-03 3:30-4:00PM Globes 0000-01 Audition Preparation for Professional Circus Schools 0000-01 3:30-4:30PM Acrobatics 0105-01 ages 10+ Duo Trapeze 1000-03 3:30-4:15PM Acrobatics 0250-01 Acrobatics 0225-02 Low Casting Fun 0000-04 4-Girl Spinning Cube 0100-01 3:45-4:15PM Chinese Poles 0050-02 (On hiatus for fall session) Hammock 0100-01 4:00-4:30PM Contortion 1000-01 Bungee Trapeze 0200-01 Mini Hammock 0000-03 4:00 PM 4:00 Mexican Cloud Swing 0200-01 4:15-5:00PM Dance 1000-04 Duo Trapeze 1000-01 4:15-5:00PM Flying Trapeze 0500-01 Duo Unicycle 1000-01 Star 0100-01 Aerial Experience 0000-01 ages 8-12 Globes 0000-02 Hammock 0200-01 4:30-5:00PM Intro to Solo Trapeze 0000-01 Mini Hammock 0000-02 Toddlers 0300-01 ages 4-5 Banquine 0100-01 Handstands 0005-01 ages 12+ Acrobatic Jump Rope 1000-01 Multiple Trapeze 0200-05 Moroccan Pyramids 0100-01 Bungee Trapeze -

SANCA Is Hiring Acrobatics Coach School of Acrobatics and New Circus Arts

SANCA is hiring Acrobatics Coach School of Acrobatics and New Circus Arts Reports to: Acrobatics Department Manager and Program Director Description: Circus is a joyful and empowering activity, and we are searching for an acrobatics coach to be- come an integral member of our staff, instructing students ages 7-99 in the circus arts. This is a part time posi- tion with an anticipated commitment of 10-25 hours each week. SANCA classes run for 12-week sessions, our coaches must commit to teaching for the entire session. Class sizes will vary based on on the ages and level of students in the class; the average number of students per class is typically 6 to 8. Teaching at SANCA can be simultaneously challenging and rewarding. We are looking for someone who has a passion for empowering students, who can easily adapt to rapidly changing and unexpected situations, and who will act as a positive role model for our students. Applicants should be comfortable coaching beginning through advanced progressions in one or more of these disciplines: Tumbling: forward rolls, cartwheels,back-extension rolls, dive rolls, walk-overs, handsprings,front/side aerials, flips and tumbling passes. Trampoline: proper jumping technique, position jumps, handsprings, flips; pulling lines to spot for double backs and twisting skills Handstands: straight circus-style handstand alignment, strength and flexibility skills to help obtain the handstand line, progressions into one arm, crocodile, familiar with the use of hand stand canes Partnered Acrobatics: L-basing skills and progressions to standing acrobatics, banquine, russian bar, dance adagio Contortion: pagoda progressions, splits, needle scales, forearm-stands, deep stretching techniques, active flexibility Job Duties and Responsibilities: - Adhere to SANCA’s policies, objectives and rules - Support SANCA’s Mission and Vision - Coach circus classes with an emphasis on safety, positivity, and small steps to success. -

Acrobatics Acts, Continued

Spring Circus Session Juventas Guide 2019 A nonprofit, 501(c)3 performing arts circus school for youth dedicated to inspiring artistry and self-confidence through a multicultural circus arts experience www.circusjuventas.org Current Announcements Upcoming Visiting Artists This February, we have THREE visiting artists coming to the big top. During the week of February 4, hip hop dancer and choreographer Bosco will be returning for the second year to choreograph the Teeterboard 0200 spring show performance along with a fun scene for this summer's upcoming production. Also arriving that week will be flying trapeze expert Rob Dawson, who will attend all flying trapeze classes along with holding workshops the following week. Finally, during our session break in February, ESAC Brussels instructor Roman Fedin will be here running Hoops, Mexican Cloud Swing, Silks, Static, Swinging Trapeze, Triple Trapeze, and Spanish Web workshops for our intermediate-advanced level students. Read more about these visiting artists below: BOSCO Bosco is an internationally renowned hip hop dancer, instructor, and choreographer with over fifteen years of experience in the performance industry. His credits include P!nk, Missy Elliott, Chris Brown, 50 Cent, So You Think You Can Dance, The Voice, American Idol, Shake It Up, and the MTV Movie Awards. Through Bosco Dance Tour, he’s had the privilege of teaching at over 170 wonderful schools & studios. In addition to dance, he is constantly creating new items for BDT Clothing, and he loves honing his photo & video skills through Look Fly Productions. Bosco choreographed scenes in STEAM and is returning for his 2nd year choreographing spring and summer show scenes! ROB DAWSON As an aerial choreographer, acrobatic equipment designer, and renowned rigger, Rob Dawson has worked with entertainment companies such as Cirque du Soleil, Universal Studios, and Sea World. -

Equestrian Vaulting

www.americanvaulting.org 1 EQUESTRIAN EQUESTRIAN VAULTING VAULTING Editor in Chief: Megan Benjamin Guimarin, [email protected] American Vaulting Association Directory Copy Editor: Katharina Woodman Photographers: Mackenzie Bakewell/ZieBee Media, Roy Friesen, Andrea Fuchshumer, Daniel Kaiser/ 2016 AVA VOLUNTEER BOARD OF DIRECTORS Impressions, Devon Maitozo, Diana Sutera Mow, Sue Rose, Ali Smith, Sarah Twohig Effective January 1, 2016 Writers and Contributors: Mackenzie Bakewell, Carol Beutler, Carolyn Bland, Laura L. Bosco, Robin EXECUTIVE BOARD MembeRS Bowman, Alicen Divita, Tessa Divita, Mary Garrett, Michelle Guo, Rachael Herrera, Carlee Heger, Noel President: Connie Geisler, [email protected] Martonovich, Yossi Martonovich, Mary McCormick, Devon Maitozo, Brittany O'Leary, Isabelle Parker, Executive VP: Kelley Holly, [email protected] Donna Schult, Steve Sullivan Secretary: Sheri Benjamin, [email protected] Designer: Leah Kucharek, Red Hen Design Treasurer: Jill Hobby, [email protected] Equestrian Vaulting magazine is the official publication of the American Vaulting Association. VP Competitions: Kathy Rynning, [email protected] Comments/suggestions/questions are welcome to [email protected]. VP Development: Open For information on advertising rates, how to submit editorial content and more go to VP Education: Carolyn Bland, [email protected] www.americanvaulting.org/contactus. VP Membership: Kathy Smith, [email protected] For address changes go to www.americanvaulting.org/members/memberservices and click on Membership Updates to make the change. If you are having problems receiving your copy of the Competitions Director: Emma Seely, [email protected] magazine or wish to receive additional copies, contact the AVA National Office (ph. 323-654- Education Director: Kendel Edmunds, [email protected] 0800 or email [email protected]). -

Acrobatics Acts Continued

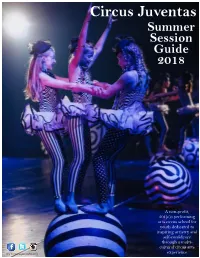

Circus Juventas Summer Session Guide 2018 A non-profit, 501(c)3 performing arts circus school for youth dedicated to inspiring artistry and self-confidence through a multi- cultural circus arts www.circusjuventas.org experience Welcome New and Returning Students! Welcome to summer session! Our Staff Table of Contents Ariel Begley Summer is a really busy time of year at Circus Student Finance Mgr CLASS INFORMATION PAGES Juventas: between summer camps, classes, and our Stacey Boucher Acrobatics Classes………………………………………………….. 12-13 annual summer show, the building is hardly ever quiet. Office Assistant Adult Classes………………………………………………………….. 11 Aerial Classes…………………………………………………………. 14-20 Rachel Butler In just three short months, over 20,000 people will be Balance Classes………………………………………………………. 20-23 Assistant Artistic Director/ coming through our doors to experience the magic of Checklist of Classes………………………………………………… 7-8 Artistic Dept. Co-Mgr Steam! Tickets go on sale Monday, June 25th and they Circus Theatre/Dance Classes…………………………………. 24 SELL FAST, so mark your calendars and tell your Sarah Butler Cross Training Classes……………………………………………. 25 Admin. Support Specialist Experience Classes…………………………………………………. 10 friends! Marissa Dorschner Juggling Classes……………………………………………………… 11 Our registration process carefully considers the Curriculum/Program Coord. Kinders Classes………………………………………………………. 9 placement of each student to find the best class for Bethany Gladhill Toddler Classes……………………………………………………… 9 their interests, skills, and schedule. This guide helps Human Resources/Financial GENERAL PROGRAM INFORMATION focus your choices. Start narrowing down by genre Manager Explanation of Class Codes……………………………………… 6 (such as an Experience class, Acrobatics, Aerial, etc). Nancy Hall Frequently Asked Questions…………………………………… 26 Use the table of contents to the right or the Student Data Systems How to Use our Class Pages…………………..………………… 6 Specialist Important Dates ……………………………………………………. -

Strongman Books Catalog

STRONGMAN BOOKS CATALOG Welcome to the Strongman Books catalog where we aim to bring you the best of the oldtime strongmen and physical culturists books and writings. This catalog shows you all of our current titles available in paperback form with links to pick them up from Amazon, everyone’s favorite place to buy books. Also at the end of this book you’ll see special package deals we offer at a substantial discount only available on our website. For an updated catalog you can always go to our website and download the latest version for free (and in full color) at www.StrongmanBooks.com . Thank you, The Strongman Books Team Alan Calvert was the creator of Milo Bar Bell Co. and the editor of Strength magazine. He was responsible for the start of many of the most famous lifters in the golden era. For this reason he has been called the grandfather of American weight lifting. Super Strength is his biggest and most well known book covering everything you need to know to develop just what the title says. In addition to 26 chapters you'll find well over 100 rare photographs. $14.95 - http://amzn.to/WZDup8 Alexander Zass was best known by his stage name, The Amazing Samson. He was an oldtime strongman capable of snapping chains and bending iron bars. In fact, the legend is he was able to escape a POW camp by doing just that. From this and other training over his lifetime he was a huge proponent of isometric training. This book, The Amazing Samson, describes his life, his training and how to do many of the feats, including chain breaking and nail driving and pulling.