INDIA Gujarat Earthquake Recovery Program Assessment Report PART II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Office of the Deputy Conservator Forest Social Forestry Division, Ahmedabad Hansol Nursery, Near Indira Bridge, Hansol

FORMAT . I Office of the Deputy Conservator Forest Social Forestry Division, Ahmedabad Hansol nursery, Near Indira Bridge, Hansol ), No:C/ FCN 7t6:1 iO" ! 6.0rc.,7 Date: 10312017 To, Senior manager, Reliance Jiolnfocom Limited, "Vraj" Building, Opp. HDFC Bank. Near Suvidha Shopping Center, Paldi, Ahmedabad. Sub:- Diversion of 0.07875 ha. Of Protected Forest Land for grant of permission for laying I Optical Fiber cable along the From Mehsana /Ahmedabad Distrrct limit Near, Becharaji (Essar pump to Ahmedabad/Surendranagar District Surendranagar Iimit (HansalpurVillege) via Maruti Suzuki plant on S.H. -19, Total- 1.751Ha.0.07875. Ref.: 1. Government of Gujarat, Forest & Environment Department Letter No. FCtu1 01 5t 10 1 /1 5/SF-B3F(1 ) Dt.04l 02t201 6 2. (Reliance Jlo Limited) Letter No. RJlLiGuj/P.ForesUAhmedabad/NLD-5/02 Dated.14112l16 Sir, I am directed to invite a Reference to your letter no. RJlLiGuj/P.ForesUAhmedabadl NLD-5/02 dated 14112116on the above mentioneci subject seeking prior approval of Government under section-2 of the Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980 as per following Sr. Particular Length X Area (Sq. No Width(Meter) Meter) n Mehsana /Ahmedabad District limit Near, 1750 0.45 787.5 Bechar;haraji (Essar pump to Ahmedabad/ Surendendranagar District:Surendranagar limit (Hansansalpur Villege) via Maruti Suzuki plant on s.H.. -19-1 (Startinrrting Point: 23" 29' 30:41",72" 0'1' 33.56" to Endinglinq Point: 23" 29'23.89", 72' 00'35.56") 747 R Government of Gujarat Forest & Environment Department Gandhinagar Via its Circular -r,entioned -

Reconstruction & Renewal of Bhuj City

Reconstruction & Renewal of Bhuj City The Gujarat Earthquake Experience - Converting Adversity into an Opportunity a presentation by: Rajesh Kishore, CEO, Gujarat State Disaster Management Authority Gujarat, India Bhuj City – Key Facts A 500 year old traditional unplanned city Headquarters of Kutch district – seat of district government Population of about 1,50,000 Strong Livelihood base - handicrafts and handloom work Disaster Profile ¾ Earthquakes – Active seismic faults surround the city ¾ Drought – every alternate year 2370 dead, 3187 injured One of the 6402 houses destroyed worst affected cities 6933 houses damaged in the earthquake of 2001 + markets, offices, civic Infrastructure etc 2 Vulnerability of Urban Areas – Pre-Earthquake ¾ Traditionally laid out city - Historical, old buildings with poor quality of construction ¾ Poor accessibility in city areas for immediate evacuation, rescue and relief operations ¾ Inadequate public sensitivity for disaster preparedness ¾ Absence of key institutions for disaster preparedness urban planning, emergency response, disaster mitigation ¾ Inadequate and inappropriate equipment/ facilities/ manpower for search and rescue capabilities 3 URBAN RE-ENGINEERING GUIDING PRINCIPLES ¾ RECONSTRUCTION AS A DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY - Provide a Better Living Environment ¾ DEVELOPING MULTI-HAZARD RESISTANT CAPABILITY - Improved Technologies and Materials e.g; ¾ ENSURING PUBLIC PARTICIPATION - In Planning and Implementation ¾ PLANNING URBAN RE-ENGINEERING - On Scientific and Rational Criteria ¾ RESTORING -

Feasibility Report for the Proposed 100 MW Wind Power Project in Gujarat

Feasibility report for the proposed 100 MW wind power project in Gujarat Prepared for Gujarat State Petrolem Corporation Limited Project Report No. 2008RT07 The Energy and Resources Institute October 2008 Feasibility report for the proposed 100 MW wind power project in Gujarat Prepared for Gujarat State Petrolem Corporation Limited Project Report No 2008RT07 w w w .te ri in .o rg The Energy and Resources Institute © The Energy and Resources Institute 2008 Suggested format for citation T E R I. 2008 Feasibility report for the proposed 100 MW wind power project in Gujarat New Delhi: The Energy and Resources Institute. [Project Report No. 2008RT07] For more information Project Monitoring Cell T E R I Tel. 2468 2100 or 2468 2111 Darbari Seth Block E-mail [email protected] IHC Complex, Lodhi Road Fax 2468 2144 or 2468 2145 New Delhi œ 110 003 Web www.teriin.org India India +91 • Delhi (0) 11 Contents Page No. Suggested format for citation ........................................................................................ 4 For more information.................................................................................................... 4 Executive summary....................................................................................................... 1 1. Methodology adopted for Feasibility Study.............................................................. 4 2. Renewable energy..................................................................................................... 4 3. Wind energy ........................................................................................................... -

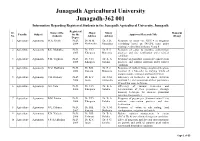

Junagadh Agricultural University Junagadh-362 001

Junagadh Agricultural University Junagadh-362 001 Information Regarding Registered Students in the Junagadh Agricultural University, Junagadh Registered Sr. Name of the Major Minor Remarks Faculty Subject for the Approved Research Title No. students Advisor Advisor (If any) Degree 1 Agriculture Agronomy M.A. Shekh Ph.D. Dr. M.M. Dr. J. D. Response of castor var. GCH 4 to irrigation 2004 Modhwadia Gundaliya scheduling based on IW/CPE ratio under varying levels of biofertilizers, N and P 2 Agriculture Agronomy R.K. Mathukia Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. P. J. Response of castor to moisture conservation 2005 Khanpara Marsonia practices and zinc fertilization under rainfed condition 3 Agriculture Agronomy P.M. Vaghasia Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. B. A. Response of groundnut to moisture conservation 2005 Khanpara Golakia practices and sulphur nutrition under rainfed condition 4 Agriculture Agronomy N.M. Dadhania Ph.D. Dr. B.B. Dr. P. J. Response of multicut forage sorghum [Sorghum 2006 Kaneria Marsonia bicolour (L.) Moench] to varying levels of organic manure, nitrogen and bio-fertilizers 5 Agriculture Agronomy V.B. Ramani Ph.D. Dr. K.V. Dr. N.M. Efficiency of herbicides in wheat (Triticum 2006 Jadav Zalawadia aestivum L.) and assessment of their persistence through bio assay technique 6 Agriculture Agronomy G.S. Vala Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. B. A. Efficiency of various herbicides and 2006 Khanpara Golakia determination of their persistence through bioassay technique for summer groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) 7 Agriculture Agronomy B.M. Patolia Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. B. A. Response of pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan L.) to 2006 Khanpara Golakia moisture conservation practices and zinc fertilization 8 Agriculture Agronomy N.U. -

(PANCHAYAT) Government of Gujarat

ROADS AND BUILDINGS DEPARTMENT (PANCHAYAT) Government of Gujarat ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) FOR GUJARAT RURAL ROADS (MMGSY) PROJECT Under AIIB Loan Assistance May 2017 LEA Associates South Asia Pvt. Ltd., India Roads & Buildings Department (Panchayat), Environmental and Social Impact Government of Gujarat Assessment (ESIA) Report Table of Content 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 BACKGROUND .......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 MUKHYA MANTRI GRAM SADAK YOJANA ................................................................ 1 1.3 SOCIO-CULTURAL AND ECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT: GUJARAT .................................... 3 1.3.1 Population Profile ........................................................................................ 5 1.3.2 Social Characteristics ................................................................................... 5 1.3.3 Distribution of Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe Population ................. 5 1.3.4 Notified Tribes in Gujarat ............................................................................ 5 1.3.5 Primitive Tribal Groups ............................................................................... 6 1.3.6 Agriculture Base .......................................................................................... 6 1.3.7 Land use Pattern in Gujarat ......................................................................... -

The Reconstruction of Bhuj Case Study: Integration of Disaster

The Reconstruction of Bhuj Case Study: Integration of Disaster Mitigation into Planning and Financing Urban Infrastructure after an Earthquake B.R. Balachandran Introduction to EPC and its Involvement in Bhuj The Environmental Planning Collaborative (EPC), established in 1996, is a not for profit, private, professional planning and development management company. The company provides professional consultancy services primarily to urban local bodies including municipal corporations and urban development authorities. EPC also works with a variety of other agencies involved in urban development such as state government departments, international funding and lending agencies, special purpose vehicles for urban development and non-government/autonomous organizations. Most projects are undertaken in a collaborative and participatory manner with significant involvement from the client, major stakeholders and other related agencies. EPC’s work is primarily of four types: (1) urban and regional development planning, (2) environmental and policy planning, (3) development management and (4) research and development. Immediately after the earthquake, EPC deputed its personnel in Bhuj to study the situation and initiate public consultations. This evolved into a USAID funded project entitled “Initiative for Planned and Participatory Reconstruction in Kutch” (IPPR) in collaboration with The Communities Group International (TCGI). The IPPR consisted of experiments in participatory planning at the regional level and in urban and rural communities. This was followed by a United States-Asia Environmental Partnership (USAEP)-funded project, “Atlas for Post-Disaster Reconstruction” under which EPC in collaboration with the Planning and The Reconstruction of Bhuj Development Company (PADCO) prepared maps of the four towns showing plot level information on intensity of damage, land use and number of floors. -

BHUJ "Ancient Temples, Tall Hills and a Deep Sense of Serenity" Bhuj Tourism

BHUJ "Ancient temples, tall hills and a deep sense of serenity" Bhuj Tourism A desert city with long history of kings and empires make Bhuj one of the most interesting and unique historical places to see. The city has a long history of kings and empires - and hence many historic places to see. The city was left in a state of devastation after the 2001 earthquake and is still in the recovery phase. Bhuj connects you to a range of civilizations and important events in South Asian history through prehistoric archaeological finds, remnants of the Indus Valley Civilization (Harappan), places associated with the Mahabharata and Alexander the Great's march into India and tombs, palaces and other buildings from the rule of the Naga chiefs, the Jadeja Rajputs, the Gujarat Sultans and the British Raj. The vibrant and dynamic history of the area gives the area a blend of ethnic cultures. In a walk around Bhuj, you can see the Hall of Mirrors at the Aina Mahal; climb the bell tower of the Prag Mahal next door; stroll through the produce market; have a famous Kutchi pau bhaji for lunch; examine the 2000-year-old Kshatrapa inscriptions in the Kutch Museum; admire the sculptures of Ramayana characters at the Ramakund stepwell; walk around Hamirsar Lake and watch children jumping into it from the lake walls as the hot afternoon sun subsides; and catch the sunset among the chhatardis of the Kutchi royal family in a peaceful field outside the center of town. This Guide includes : About Bhuj | Suggested Itinerary | Commuting tips | Top places to visit | Hotels | Restaurants | Related Stories Commuting in Bhuj Tuk-tuks (autorickshaws) are the best way to travel within the city. -

Annex 7 Municipal and Environmental Infrastructure

Annex 7 Municipal and Environmental Infrastructure Introduction Gujarat has 6 municipal corporations and 143 municipal towns. Of these, 5 municipal corporations1/ and 57 municipal towns have been affected by the earthquake. The assessment team visited the worst hit towns such as Bhuj, Anjar, Bhachau, Rapar and Gandhidham in Kutch district and moderately hit Ahmedabad city during February 13 to 17, 2001 to review the damages caused to the urban and municipal infrastructure and the repairs, rehabilitation and reconstruction needs. The assessment team also received briefing from the state government and the municipal staff. From the various reports provided by the GOG and from discussions the assessment team held in the field, it was observed that the government machinery moved quite expeditiously to the affected urban areas and the basic services were restored although at a significantly lower scale. Delimitation of the Affected Area The impact of the earthquake on the municipal infrastructure varied widely among the districts. Severe damages were caused in several towns in Kutch, Rajkot and Surendranagar districts and some damages to several cities/towns in the remaining districts. Municipal infrastructure in Ahmedabad city also suffered damages. Based on available information, urban infrastructure in 15 cities were damaged to significant degree. The table below summarizes the major impacts district-wise. Damages were reported from other Corporation/ Municipalities, but details were not readily available. The Urban Development Dept., GOG (UDD) is currently conducting a detailed survey of the damages in the municipal areas and results are awaited. Affected Municipality/City Severely Affected District Kutch Bhuj, Anjar, Rapar, Bhachau, Gandhidham, Mandvi Rajkot Morvi, Wankaner Surendranagar Surendranagar, Limdi, Thangadh, Dhrangadhra, Halwad, Wadhwan Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Situation Prior to Disaster Event Ahmedabad, Vadodara, Rajkot, Surat, and Jamnagar are the large cities which suffered medium to low damages. -

Surendranagar Index

SURENDRANAGAR INDEX 1 Surendranagar: A Snapshot 2 Economy and Industry Profile 3 Industrial Locations / Infrastructure 4 StIfttSupport Infrastructure 5 Social Infrastructure 6 Tourism 7 IttOtitiInvestment Opportunities 8 Annexure 2 1 Surendranagar: A Snapshot 3 Introduction: Surendranagar Map1: District Map of Surendranagar with Surendranagar district is located in the central region of Talukas Gujarat, in the Saurashtra peninsula The district comprises of 10 talukas. Developed amongst them are Surendranagar, Wadhwan, Limbdi, Chotila, Dhrangadhra, and Lakhtar Surendranagar is one of the largest producers of “Shankar” Cotton in the world and, is also the home to the first cotton Patdi trading exchange in India Haaadlwad Dhangadhra Focus idindus try sectors are ttiltextiles, chilhemicals, and Lakhtar ceramics Surendranagar Muli Wadhawan Limbdi Some of the major tourist destinations in the district are Sayla Chuda Tarnetar Mela, Chotila Hills and Ranakdevi Temple Chotila District Headquarter Talukas 4 Fact File 69.45º to 72.15º East ((gLongitude) Geographical location 22.00º to 23.04º North (Latitude) 45.6º Centigrade (Maximum) Temperature 7.8º Centigg(rade (Minimum) Average Rainfall 760 mm Bhogavo, Sukhbhadar, Brahmani, Kankavati, Vansal, Rupen, Falku, Rivers Vrajbhama, Umai, and Chandrabhaga Area 10,489 sq. km District Headquarter Surendranagar Talukas 10 Population 15,15,147 (As per 2001 Census) Population Density 144 Persons per sq. Km Sex Ratio 924 Females per 1000 Males Literacy Rate 61.6% Languages Gujarati, Hindi, and English -

The Best Heritage Hotels of Gujarat

MARCH 2012 Royal THE BEST HERITAGE HOTELS OF H o l i d a y s GUJARAT Covers THE BEACH AT MANDVI PALACE RIVERSIDE PALACE PHOTOGRAPHS BY DINESH SHULKA NORTH GUJARAT 6 BALARAM PALACE RESORT 7 VIJAY VILLAS 8 BHAVANI VILLA 9 DARBARGADH POSHINA Champaner, a CENTRAL GUJARAT UNESCO World Architecture at the 11 THE HOUSE OF MG Heritage Site Adalaj stepwell in ARTS REVERIE Central Gujarat 12 13 CORPORATE SUITES Publisher THE KING WHO CHALLENGED THE BRITISH MALA SEKHRI KUTCH & SAURASHTRA Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad, ruler of the Baroda princely state from 1875-1839, was Editor 15 DARBARGADH PALACE one of the most respected rulers, known for his economic, educational, judicial, and SUJATA ASSOMULL SIPPY 16 OLD BELL GUEST HOUSE social reforms. He jealously guarded his rights and status on matters of principle and Creative Director NUPUR MEHTA PURI 19 HERITAGE KHIRASAR PALACE governance, often picking disputes with the British residents and Viceroy. At the 1911 Executive Editor RAJMAHAL PALACE Delhi Durbar, attended by George V, each Indian ruler or ‘native prince’, was expected PRIYA KUMARI RANA 20 Associate Editor 22 GOPNATH BUNGALOW to perform proper obeisance to the King-Emperor by bowing three times before him. PREETIKA MATHEW SAHAY Sayajirao was third in line, after the Nizam of Hyderabad and Maharaja of Mysore, and refused to wear his full regalia of jewels and honours; neither did he bow, or maybe just Text by ANIL MULCHANDANI bowed briefly before turning his back on the King-Emperor. Images by DINESH SHUKLA ART EASTERN GUJARAT Assistant Art Director GARDEN PALACE PROGRESSIVE MAHARAJAS YURREIPEM ARTHUR 27 Contrary to popular belief, the life of the princes was not just about fun, games, shoots, Senior Designer 28 RAJVANT PALACE RESORT NIKHIL KAUSHIK and frolic. -

Toposheet of the Side Plan , Taluka & Dist

Toposheet of The Side Plan , Taluka & Dist. District : Jamnagar For official use only Location Map COMMISSIONERATE OF GEOLOGY AND MINING Industries and Mines Department, Government of Gujarat Legend: District Boundary " District Headquarter ± Mud flat BANAS KANTHA Area : 14125 Sq.km Area under forest : 382.63 Sq.km No. of Talukas : 10 MAHESANA PATAN No. of Villages : 756 SABAR KANTHA KACHCHH No. of Towns : 10 Total Population : 1904278 GANDHINAGAR Male Population : 981320 PANCH MAHALS AHMEDABAD Female Population : 922958 KHEDA DOHAD SURENDRANAGAR " ANAND RAJKOT VADODARA JAMNAGAR BHARUCH NARMADA PORBANDAR BHAVNAGAR AMRELI JUNAGADH SURAT NAVSARI THE DANGS VALSAD Location Index: INDIA GUJARAT Gujarat District : Jamnagar External boundaries are not authenticated * Maps are not to the Scale Prepared by: 1 ISO 9001:2000 For official use only District : Jamnagar Geological Map COMMISSIONERATE OF GEOLOGY AND MINING Industries and Mines Department, Government of Gujarat The Map shows information regarding geological formations of different ages and their respective lithology. Geology: LITHOLOGY AGE ALLUVIUM BLOWN SAND RECENT- HOLOCENE MILIOLITE LIMESTONE PLEISTOCENE JODIYA MIOCENE ! SHALES, MARLS AND SANDSTONES GYPSIFEROUS CLAYS & SANDY LIMESTONES DWARKA BEDS LATERITE AND BAUXITE PALAEOCENE TO EOCENE BASIC INTRUSIVE PALAEOCENE TO UPPER CRETACEOUS DH!ROL TRAP LOWER EOCENE TO UPPER CRETACEOUS "! DIORITES UPPER CRETACEOUS TO PALAEOCENE JAMNAGAR FELSITE,RHYOLITE & PITCHSTONE FLOWS DECCAN TRAP OHKAMANDAL ! LALPUR KHAMBHALIA! ! Legend: ! KALAVAD District Boundary Taluka Boundary KALYANPUR " ! District Headquarter ! Taluka Headquarter B!HANVAD JAMJODHPUR Mudflat ! Location Index: GUJARAT District : Jamnagar ± External boundaries are not authenticated 5 * Maps are not to the Scale Prepared by: ISO 9001:2000 District : Jamnagar For official use only Mineral Map COMMISSIONERATE OF GEOLOGY AND MINING Industries and Mines Department, Government of Gujarat The Map shows information of Mineral occurances of Jamnagar District. -

08Kutch Kashmireq.Pdf

Key Idea From Kutch to Kashmir: Lessons for Use Since, October 11, 2005 early hours AIDMI team is in Kashmir assessing losses and needs. The biggest gap found is of understanding earthquake. Five key gaps are addressed here. nderstanding India's vulnerability: Using earthquake science to enhance Udisaster preparedness Every year, thousands flock to Kashmir, in India and Pakistan to marvel at her spectacular scenery and majestic mountain ranges. However, the reality of our location and mountainous surroundings is an inherent threat of devastating earthquakes. In addition to accepting earthquakes as a South Asian reality, we as humanitarian respondents as well as risk reduction specialists must now look to science to enhance disaster risk mitigation and preparedness.The humanitarian communalities know little about what scientific communities have discovered and what could be used to mitigate risk of earthquakes. Similarly, scientific communities need to know how to put scientific knowledge in mitigation perspective from the point of view of non-scientific communities. How do we bridge this gap? We at AIDMI acknowledged this gap, and from the overlapping questions, we selected four key areas relevant to Kashmir and South Asia and discussed them in this issue. Editorial Advisors: How do we use scientific knowledge on earthquakes? Dr. Ian Davis Certain regions of South Asia are more vulnerable to earthquakes than others. Kashmir Cranfield University, UK ranks high on this list. Fortunately, geologists know which regions are more vulnerable Kala Peiris De Costa and why. When this information is disseminated to NGOs, relief agencies and Siyath Foundation, Sri Lanka governments, they can quickly understand where investments, attention and disaster Khurshid Alam preparedness measures should be focussed.