CCS Grant Report, 2004 This Report Was Submitted in Fulfilment of A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Improved Service Methodology

2006/7 A N I M P R O V E D S E R V I C E M E T H O D O L O G Y A N ote F rom the D epartment The Department of Community Safety, Western Cape is responsible for the coordination and implementation of community based social crime prevention and oversight over the South African Police Services (SAPS), amongst other key performances. Key to the Department’s approach is a transformatory and participatory methodology supported by the National Crime Prevention Strategy (NCPS, 1996) and the ikapa Growth and Development White Paper (2007). This integrated service delivery programme is implemented via Bambanani “Unite” Against Crime (Bambanani Strategy). The Bambanani Strategy is over-arching to the entire Department and is premised on the principles outlined in Batho Pele and the notion of a developmental state. Minister Leonard Ramatlakane Under the direct guidance of Minister Leonard Ramatlakane and I, the Directorates: Community Liaison Minister of Community Safety and Social Crime Prevention are responsible for the design and implementation of the Bambanani Western Cape “Unite” Against Crime Strategy. The Directorate: Strategic Services and Communication and the Directorate: Safety Information and Research is responsible for researching, documenting and sharing strategies, methodologies and information respectively with internal and external stakeholders. The Best Practice document in the form of An Improved Service Delivery Methodology 2007/08 aims to share the experiences and expose other Departments to the implementation strategies employed by the Department of Community Safety, in its efforts to transform delivery through encouraging community participation, community empowerment, social cohesion, social capital and deliver services that reflect public value. -

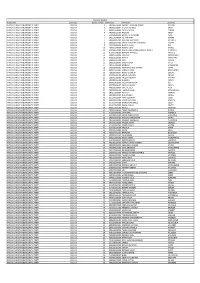

LIST of MEMBERS (Female)

As on 28 May 2021 LIST OF MEMBERS (Female) 6th Parliament CABINET OFFICE-BEARERS OF THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY MEMBERS OF THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY As on 28 May 2021 MEMBERS OF THE EXECUTIVE (alphabetical list) Minister of Agriculture, Land Reform and Rural Development ............. Ms A T Didiza Minister of Basic Education ....................................................... Mrs M A Motshekga Minister of Communications and Digital Technologies ....................... Ms S T Ndabeni-Abrahams Minister of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs ............... Dr N C Dlamini-Zuma Minister of Defence and Military Veterans ..................................... Ms N N Mapisa-Nqakula Minister of Forestry, Fisheries and Environment ............................... Ms B D Creecy Minister of Human Settlements, Water and Sanitation ...................... Ms L N Sisulu Minister of International Relations and Cooperation ......................... Dr G N M Pandor Minister of Public Works and Infrastructure ................................... Ms P De Lille Minister of Small Business Development ....................................... Ms K P S Ntshavheni Minister of Social Development .................................................. Ms L D Zulu Minister of State Security ......................................................... Ms A Dlodlo Minister of Tourism ................................................................. Ms M T Kubayi-Ngubane Minister in The Presidency for Women, Youth and Persons with Disabilities ..................................................................... -

Party List Rank Name Surname African Christian Democratic Party

Party List Rank Name Surname African Christian Democratic Party National 1 Kenneth Raselabe Joseph Meshoe African Christian Democratic Party National 2 Steven Nicholas Swart African Christian Democratic Party National 3 Wayne Maxim Thring African Christian Democratic Party Regional: Western Cape 1 Marie Elizabeth Sukers African Independent Congress National 1 Mandlenkosi Phillip Galo African Independent Congress National 2 Lulama Maxwell Ntshayisa African National Congress National 1 Matamela Cyril Ramaphosa African National Congress National 2 David Dabede Mabuza African National Congress National 3 Samson Gwede Mantashe African National Congress National 4 Nkosazana Clarice Dlamini-Zuma African National Congress National 5 Ronald Ozzy Lamola African National Congress National 6 Fikile April Mbalula African National Congress National 7 Lindiwe Nonceba Sisulu African National Congress National 8 Zwelini Lawrence Mkhize African National Congress National 9 Bhekokwakhe Hamilton Cele African National Congress National 10 Nomvula Paula Mokonyane African National Congress National 11 Grace Naledi Mandisa Pandor African National Congress National 12 Angela Thokozile Didiza African National Congress National 13 Edward Senzo Mchunu African National Congress National 14 Bathabile Olive Dlamini African National Congress National 15 Bonginkosi Emmanuel Nzimande African National Congress National 16 Emmanuel Nkosinathi Mthethwa African National Congress National 17 Matsie Angelina Motshekga African National Congress National 18 Lindiwe Daphne Zulu -

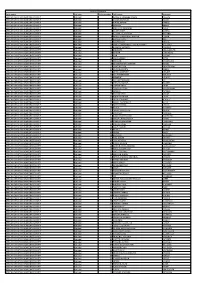

Candidates List 2019 Elections

AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS CANDIDATES LIST 2019 ELECTIONS NATIONAL TO NATIONAL 1. MATAMELA CYRIL RAMAPHOSA 2. DAVID DABEDE MABUZA 3. SAMSON GWEDE MANTASHE 4. NKOSAZANA CLARICE DLAMINI-ZUMA 5. RONALD OZZY LAMOLA 6. FIKILE APRIL MBALULA 7. LINDIWE NONCEBA SISULU 8. ZWELINI LAWRENCE MKHIZE 9. BHEKOKWAKHE HAMILTON CELE 10. NOMVULA PAULA MOKONYANE 11. GRACE NALEDI MANDISA PANDOR 12. ANGELA THOKOZILE DIDIZA 13. EDWARD SENZO MCHUNU 14. BATHABILE OLIVE DLAMINI 15. BONGINKOSI EMMANUEL NZIMANDE 16. EMMANUEL NKOSINATHI MTHETHWA 17. MATSIE ANGELINA MOTSHEKGA 18. LINDIWE DAPHNE ZULU 19. DAVID MASONDO 20. THANDI RUTH MODISE 21. MKHACANI JOSEPH MASWANGANYI 22. TITO TITUS MBOWENI 23. KNOWLEDGE MALUSI NKANYEZI GIGABA 24. JACKSON MPHIKWA MTHEMBU 25. PAKISHE AARON MOTSOALEDI 1 ANC CANDIDATES 2019 NATIONAL TO NATIONAL 26. KGWARIDI BUTI MANAMELA 27. STELLA TEMBISA NDABENI-ABRAHAMS 28. MBANGISENI DAVID MAHLOBO 29. DIPUO BERTHA LETSATSI-DUBA 30. TOKOZILE XASA 31. NCEDISO GOODENOUGH KODWA 32. JEFFREY THAMSANQA RADEBE 33. NOCAWE NONCEDO MAFU 34. NOSIVIWE NOLUTHANDO MAPISA-NQAKULA 35. MAITE EMILY NKOANA-MASHABANE 36. CASSEL CHARLIE MATHALE 37. AYANDA DLODLO 38. MILDRED NELISIWE OLIPHANT 39. GODFREY PHUMULO MASUALLE 40. PEMMY CASTELINA PAMELA MAJODINA 41. BONGANI THOMAS BONGO 42. NOXOLO KIVIET 43. MMAMOLOKO TRYPHOSA KUBAYI-NGUBANE 44. BALEKA MBETE 45. MONDLI GUNGUBELE 46. SIDUMO MBONGENI DLAMINI 47. MOKONE COLLEN MAINE 48. PINKY SHARON KEKANA 49. TANDI MAHAMBEHLALA 50. MATHUME JOSEPH PHAAHLA 51. VIOLET SIZANI SIWELA 52. FIKILE DEVILLIERS XASA 53. BARBARA DALLAS CREECY 54. SIYABONGA CYPRIAN CWELE 55. RHULANI THEMBI SIWEYA 56. ALVIN BOTES 57. MAKGABO REGINAH MHAULE 58. SUPRA OBAKENG RAMOELETSI MAHUMAPELO 59. PHINDISILE PRETTY XABA-NTSHABA 60. THEMBELANI WALTERMADE THULAS NXESI 2 ANC CANDIDATES 2019 NATIONAL TO NATIONAL 61. -

LIST of MEMBERS (Female)

As on 23 April 2021 LIST OF MEMBERS (Female) 6th Parliament CABINET OFFICE-BEARERS OF THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY MEMBERS OF THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY As on 23 April 2021 MEMBERS OF THE EXECUTIVE (alphabetical list) Minister of Agriculture, Land Reform and Rural Development ............. Ms A T Didiza Minister of Basic Education ....................................................... Mrs M A Motshekga Minister of Communications and Digital Technologies ....................... Ms S T Ndabeni-Abrahams Minister of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs ............... Dr N C Dlamini-Zuma Minister of Defence and Military Veterans ..................................... Ms N N Mapisa-Nqakula Minister of Forestry, Fisheries and Environment ............................... Ms B D Creecy Minister of Human Settlements, Water and Sanitation ...................... Ms L N Sisulu Minister of International Relations and Cooperation ......................... Dr G N M Pandor Minister of Public Works and Infrastructure ................................... Ms P De Lille Minister of Small Business Development ....................................... Ms K P S Ntshavheni Minister of Social Development .................................................. Ms L D Zulu Minister of State Security ......................................................... Ms A Dlodlo Minister of Tourism ................................................................. Ms M T Kubayi-Ngubane Minister in The Presidency for Women, Youth and Persons with Disabilities ..................................................................... -

General Notices • Algemene Kennisgewings

Reproduced by Data Dynamics in terms of Government Printers' Copyright Authority No. 9595 dated 24 September 1993 4 No. 42460 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 15 MAY 2019 GENERAL NOTICE GENERAL NOTICES • ALG EMENE KENNISGEWINGS NOTICEElectoral Commission/….. Verkiesingskommissie OF 2019 ELECTORAL COMMISSION ELECTORALNOTICE 267 COMMISSION OF 2019 267 Electoral Act (73/1998): List of Representatives in the National Assembly and Provincial Legislatures, in respect of the elections held on 8 May 2019 42460 ELECTORAL ACT, 1998 (ACT 73 OF 1998) PUBLICATION OF LISTS OF REPRESENTATIVES IN THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY AND PROVINCIAL LEGISLATURES IN TERMS OF ITEM 16 (4) OF SCHEDULE 1A OF THE ELECTORAL ACT, 1998, IN RESPECT OF THE ELECTIONS HELD ON 08 MAY 2019. The Electoral Commission hereby gives notice in terms of item 16 (4) of Schedule 1A of the Electoral Act, 1998 (Act 73 of 1998) that the persons whose names appear on the lists in the Schedule hereto have been elected in the 2019 national and provincial elections as representatives to serve in the National Assembly and the Provincial Legislatures as indicated in the Schedule. SCHEDULE This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za Reproduced by Data Dynamics in terms of Government Printers' Copyright Authority No. 9595 dated 24 September 1993 NATIONAL ASSEMBLY LIST Party List Rank ID Name Surname AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 1 5401185719080 KENNETH RASELABE JOSEPH MESHOE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 2 5902085102087 STEVEN NICHOLAS SWART AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC -

Vol. 647 15 May 2019 No

Vol. 647 15 May 2019 No. 42460 Mei 2 No.42460 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 15 MAY 2019 STAATSKOERANT, 15 MEl 2019 No.42460 3 Contents Gazette Page No. No. No. GENERAL NOTICES • ALGEMENE KENNISGEWINGS Electoral Commission! Verkiesingskommissie 267 Electoral Act (73/1998): List of Representatives in the National Assembly and Provincial Legislatures, in respect of the elections held on 8 May 2019 ............................................................................................................................ 42460 4 4 No.42460 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 15 MAY 2019 GENERAL NOTICES • ALGEMENE KENNISGEWINGS ELECTORAL COMMISSION NOTICE 267 OF 2019 ELECTORAL ACT, 1998 (ACT 73 OF 1998) PUBLICATION OF LISTS OF REPRESENTATIVES IN THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY AND PROVINCIAL LEGISLATURES IN TERMS OF ITEM 16 (4) OF SCHEDULE 1A OF THE ELECTORAL ACT, 1998, IN RESPECT OF THE ELECTIONS HELD ON 08 MAY 2019. The Electoral Commission hereby gives notice in terms of item 16 (4) of Schedule 1A of the Electoral Act, 1998 (Act 73 of 1998) that the persons whose names appear on the lists in the Schedule hereto have been elected in the 2019 national and provincial elections as representatives to serve in the National Assembly and the Provincial Legislatures as indicated in the Schedule. SCHEDULE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY LIST Party List Rank ID Name ~urname AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 1 5401185719080 KENNETH RASELABE JOSEPH MESHOE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 2 5902085102087 STEVEN NICHOLAS SWART AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 3 6302015139086 -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South

VOLUME FIVE Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 Analysis of Gross Violations of Findings and Conclusions ........................ 196 Human Rights.................................................... 1 Appendix 1: Coding Frame for Gross Violations of Human Rights................................. 15 Appendix 2: Human Rights Violations Hearings.................................................................... 24 Chapter 7 Causes, Motives and Perspectives of Perpetrators................................................. 259 Chapter 2 Victims of Gross Violations of Human Rights.................................................... 26 Chapter 8 Recommendations ......................................... 304 Chapter 3 Interim Report of the Amnesty Chapter 9 Committee ........................................................... 108 Reconciliation ................................................... 350 Appendix: Amnesties granted............................ 119 Minority Position submitted by Chapter 4 Commissioner -

Party Name List Type Order Number Idnumber Full Names Surname

National NPE2019 Party name List type Order number IDNumber Full names Surname AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 1 5401185719080 KENNETH RASELABE JOSEPH MESHOE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 2 5902085102087 STEVEN NICHOLAS SWART AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 3 6302015139086 WAYNE MAXIM THRING AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 4 7403090279083 NOSIZWE ABADA AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 5 5602145803084 MOKHETHI RAYMOND TLAELI AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 6 5901170249084 JO-ANN MARY DOWNS AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 7 5804220857080 KEITUMETSE PATRICIA MATANTE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 8 6802235024083 GRANT CHRISTOPHER RONALD HASKIN AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 9 7810230406089 BERNICE PEARL OSA AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 10 7304165540088 MZUKISI ELIAS DINGILE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 11 6812205532080 DAVID EUGENE MOSES JOSHUA BARUTI NTSHABELE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 12 8612075246086 BONGANI MAXWELL KHANYILE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 13 6108055129089 ANNIRUTH KISSOONDUTH AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 14 8709135113080 MARVIN CHRISTIANS AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 15 5403065155088 IVAN JARDINE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 16 6302220199081 LINDA MERIDY YATES AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 17 7905155604088 MONGEZI MABUNGANI AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 18 6508220834085 KGOMOTSO -

Party Name List Type Order Number Full Names Surname AFRICAN

National NPE2019 Party name List type Order number Full names Surname AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 1 KENNETH RASELABE JOSEPH MESHOE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 2 STEVEN NICHOLAS SWART AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 3 WAYNE MAXIM THRING AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 4 NOSIZWE ABADA AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 5 MOKHETHI RAYMOND TLAELI AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 6 JO-ANN MARY DOWNS AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 7 KEITUMETSE PATRICIA MATANTE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 8 GRANT CHRISTOPHER RONALD HASKIN AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 9 BERNICE PEARL OSA AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 10 MZUKISI ELIAS DINGILE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 11 DAVID EUGENE MOSES JOSHUA BARUTI NTSHABELE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 12 BONGANI MAXWELL KHANYILE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 13 ANNIRUTH KISSOONDUTH AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 14 MARVIN CHRISTIANS AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 15 IVAN JARDINE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 16 LINDA MERIDY YATES AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 17 MONGEZI MABUNGANI AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 18 KGOMOTSO WELHEMINAH TISANE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 19 LANCE PATRICK GROOTBOOM AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 20 MARIE ELIZABETH SUKERS AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 21 MPHO LAWRENCE CHAUKE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY -

National (Incl Regional) Seats Assigned

NATIONAL ASSEMBLY LIST Party List Rank ID Name Surname AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 1 5401185719080 KENNETH RASELABE JOSEPH MESHOE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 2 5902085102087 STEVEN NICHOLAS SWART AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 3 6302015139086 WAYNE MAXIM THRING AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Regional: Western Cape 1 7206180506087 MARIE ELIZABETH SUKERS AFRICAN INDEPENDENT CONGRESS National 1 6207056007086 MANDLENKOSI PHILLIP GALO AFRICAN INDEPENDENT CONGRESS National 2 5808235950087 LULAMA MAXWELL NTSHAYISA AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS National 1 5211175681087 MATAMELA CYRIL RAMAPHOSA AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS National 2 6008255884089 DAVID DABEDE MABUZA AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS National 3 5506215193088 SAMSON GWEDE MANTASHE AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS National 4 4901270600088 NKOSAZANA CLARICE DLAMINI-ZUMA AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS National 5 8311215410088 RONALD OZZY LAMOLA AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS National 6 7104085804089 FIKILE APRIL MBALULA AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS National 7 5405100835087 LINDIWE NONCEBA SISULU AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS National 8 5602026233088 ZWELINI LAWRENCE MKHIZE AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS National 9 5202225778080 BHEKOKWAKHE HAMILTON CELE AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS National 10 6306280482089 NOMVULA PAULA MOKONYANE AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS National 11 5312070747088 GRACE NALEDI MANDISA PANDOR AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS National 12 6506020270088 ANGELA THOKOZILE DIDIZA AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS National 13 5804235826088 EDWARD SENZO MCHUNU AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS