Paoletti and Radke

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Once Again About the Style and Iconography of the Wall Paintings in the Former Dominican Church of St

arts Article Greek Painters for the Dominicans or Trecento at the Bosphorus? Once again about the Style and Iconography of the Wall Paintings in the Former Dominican Church of St. Paul in Pera Rafał Quirini-Popławski Department of History of Art, Jagiellonian University, ul. Grodzka 53, 31-001 Kraków, Poland; [email protected] Received: 20 August 2019; Accepted: 27 September 2019; Published: 11 October 2019 Abstract: The recently discovered wall paintings of the Dominican church of St. Paul are perhaps the most fascinating part of the artistic heritage of Pera, the former Genoese colony at the Bosphorus. According to the researchers analyzing the fragments discovered in 1999–2007, they follow Byzantine iconographic tradition and were executed by Greek painters representing Paleologan style close to the decoration of the Chora church. After extensive discoveries in 2012 it was made possible to describe many more fragments of fresco and mosaic decoration and to make a preliminary identification of its iconography, which appeared to be very varied in character. Many features are typical of Latin art, not known in Byzantine tradition, some even have a clearly polemical, anti-Greek character. The analysis of its iconography, on a broad background of the Byzantine paintings in Latin churches, does not answer the question if it existed and what could be the goal of creating such paintings. There is a high probability that we are dealing with choice dictated by aesthetic and pragmatic factors, like the availability of the appropriate workshop. So, the newly discovered frescoes do not fundamentally alter the earlier conclusions that we are dealing with the work of a Greek workshop, perhaps primarily operating in Pera, which had to adapt to the requirements of Latin clients. -

The Holy See (Including Vatican City State)

COMMITTEE OF EXPERTS ON THE EVALUATION OF ANTI-MONEY LAUNDERING MEASURES AND THE FINANCING OF TERRORISM (MONEYVAL) MONEYVAL(2012)17 Mutual Evaluation Report Anti-Money Laundering and Combating the Financing of Terrorism THE HOLY SEE (INCLUDING VATICAN CITY STATE) 4 July 2012 The Holy See (including Vatican City State) is evaluated by MONEYVAL pursuant to Resolution CM/Res(2011)5 of the Committee of Ministers of 6 April 2011. This evaluation was conducted by MONEYVAL and the report was adopted as a third round mutual evaluation report at its 39 th Plenary (Strasbourg, 2-6 July 2012). © [2012] Committee of experts on the evaluation of anti-money laundering measures and the financing of terrorism (MONEYVAL). All rights reserved. Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, save where otherwise stated. For any use for commercial purposes, no part of this publication may be translated, reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic (CD-Rom, Internet, etc) or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system without prior permission in writing from the MONEYVAL Secretariat, Directorate General of Human Rights and Rule of Law, Council of Europe (F-67075 Strasbourg or [email protected] ). 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. PREFACE AND SCOPE OF EVALUATION............................................................................................ 5 II. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY....................................................................................................................... -

Renaissance Art in Rome Giorgio Vasari: Rinascita

Niccolo’ Machiavelli (1469‐1527) • Political career (1498‐1512) • Official in Florentine Republic – Diplomat: observes Cesare Borgia – Organizes Florentine militia and military campaign against Pisa – Deposed when Medici return in 1512 – Suspected of treason he is tortured; retired to his estate Major Works: The Prince (1513): advice to Prince, how to obtain and maintain power Discourses on Livy (1517): Admiration of Roman republic and comparisons with his own time – Ability to channel civil strife into effective government – Admiration of religion of the Romans and its political consequences – Criticism of Papacy in Italy – Revisionism of Augustinian Christian paradigm Renaissance Art in Rome Giorgio Vasari: rinascita • Early Renaissance: 1420‐1500c • ‐‐1420: return of papacy (Martin V) to Rome from Avignon • High Renaissance: 1500‐1520/1527 • ‐‐ 1503: Ascension of Julius II as Pope; arrival of Bramante, Raphael and Michelangelo; 1513: Leo X • ‐‐1520: Death of Raphael; 1527 Sack of Rome • Late Renaissance (Mannerism): 1520/27‐1600 • ‐‐1563: Last session of Council of Trent on sacred images Artistic Renaissance in Rome • Patronage of popes and cardinals of humanists and artists from Florence and central/northern Italy • Focus in painting shifts from a theocentric symbolism to a humanistic realism • The recuperation of classical forms (going “ad fontes”) ‐‐Study of classical architecture and statuary; recovery of texts Vitruvius’ De architectura (1414—Poggio Bracciolini) • The application of mathematics to art/architecture and the elaboration of single point perspective –Filippo Brunellschi 1414 (develops rules of mathematical perspective) –L. B. Alberti‐‐ Della pittura (1432); De re aedificatoria (1452) • Changing status of the artist from an artisan (mechanical arts) to intellectual (liberal arts; math and theory); sense of individual genius –Paragon of the arts: painting vs. -

The Holy See, Social Justice, and International Trade Law: Assessing the Social Mission of the Catholic Church in the Gatt-Wto System

THE HOLY SEE, SOCIAL JUSTICE, AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE LAW: ASSESSING THE SOCIAL MISSION OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN THE GATT-WTO SYSTEM By Copyright 2014 Fr. Alphonsus Ihuoma Submitted to the graduate degree program in Law and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Juridical Science (S.J.D) ________________________________ Professor Raj Bhala (Chairperson) _______________________________ Professor Virginia Harper Ho (Member) ________________________________ Professor Uma Outka (Member) ________________________________ Richard Coll (Member) Date Defended: May 15, 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Fr. Alphonsus Ihuoma certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: THE HOLY SEE, SOCIAL JUSTICE, AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE LAW: ASSESSING THE SOCIAL MISSION OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN THE GATT- WTO SYSTEM by Fr. Alphonsus Ihuoma ________________________________ Professor Raj Bhala (Chairperson) Date approved: May 15, 2014 ii ABSTRACT Man, as a person, is superior to the state, and consequently the good of the person transcends the good of the state. The philosopher Jacques Maritain developed his political philosophy thoroughly informed by his deep Catholic faith. His philosophy places the human person at the center of every action. In developing his political thought, he enumerates two principal tasks of the state as (1) to establish and preserve order, and as such, guarantee justice, and (2) to promote the common good. The state has such duties to the people because it receives its authority from the people. The people possess natural, God-given right of self-government, the exercise of which they voluntarily invest in the state. -

The Mariology of St. Bonaventure As a Source of Inspiration in Italian Late Medieval Iconography

José María SALVADOR GONZÁLEZ, La mariología de San Buenaventura como fuente de inspiración en la iconografía bajomedieval italiana The mariology of St. Bonaventure as a source of inspiration in Italian late medieval iconography La mariología de San Buenaventura como fuente de inspiración en la iconografía bajomedieval italiana1 José María SALVADOR-GONZÁLEZ Universidad Complutense de Madrid [email protected] Recibido: 05/09/2014 Aceptado: 05/10/2014 Abstract: The central hypothesis of this paper raises the possibility that the mariology of St. Bonaventure maybe could have exercised substantial, direct influence on several of the most significant Marian iconographic themes in Italian art of the Late Middle Ages. After a brief biographical sketch to highlight the prominent position of this saint as a master of Scholasticism, as a prestigious writer, the highest authority of the Franciscan Order and accredited Doctor of the Church, the author of this paper presents the thesis developed by St. Bonaventure in each one of his many “Mariological Discourses” before analyzing a set of pictorial images representing various Marian iconographic themes in which we could detect the probable influence of bonaventurian mariology. Key words: Marian iconography; medieval art; mariology; Italian Trecento painting; St. Bonaventure; theology. Resumen: La hipótesis de trabajo del presente artículo plantea la posibilidad de que la doctrina mariológica de San Buenaventura haya ejercido notable influencia directa en varios de los más significativos temas iconográficos -

Il Capitale Culturale

21 IL CAPITALE CULTURALE Studies on the Value of Cultural Heritage eum Rivista fondata da Massimo Montella Ines Ivić, «Recubo praesepis ad antrum»: The Cult of Saint Jerome in the Church of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome at the End of the 13th Century «Il capitale culturale», n. 21, 2020, pp. 87-119 ISSN 2039-2362 (online); DOI: 10.13138/2039-2362/2234 «Recubo praesepis ad antrum»: The Cult of Saint Jerome in the Church of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome at the End of the 13th Century Ines Ivić* Abstract This paper analyzes the setting up of the cult of Saint Jerome in Rome at the end of the 13th century in the papal basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore. It observes the development of the cult as part of the renovations of the church during the pontificate of Nicholas IV and the patronage of the Colonna family. It argues that it happened during the process of Franciscanization of the church and making the ideological axis between the Roman basilica and new papal basilica in Assisi, stressed also in their pictorial decorations – the mosaics in the apse in Rome, and the Life of Saint Francis in Assisi. It also studies the construction of Jerome’s Roman identity in correlation with the confirmation of Santa Maria Maggiore church as a “second Bethlehem” after the fall of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, reflecting upon the leading proponents of the idea, architectural setting, artistic production and hagiographical texts produced to uphold this idea. *Ines Ivić, PhD Candidate, Central European University (CEU), Department of Medieval Studies, Nádor utca 9, H-1051 Budapest, e-mail: [email protected]. -

Saint Joseph on the Brandywine Founded 1841

Saint Joseph on the Brandywine Founded 1841 Rectory Schedule of Liturgies 10 Old Church Road SATURDAY VIGIL Greenville, DE 19807 5:00 PM Office (302) 658-7017 Fax (302) 428-0639 SUNDAY EUCHARISTS: www.stjosephonthebrandywine.org 7:30 AM; 9:00 AM; 10:30 AM DAILY EUCHARISTS: Rev. Msgr. Joseph F. Rebman, V.G., PASTOR 7 AM; 12:05 (Mon. - Fri.) 8:00 AM (Saturday) F. Edmund Lynch, DEACON, RCIA PROGRAM HOLY DAY EUCHARIST: As announced Parish & Pastoral Secretary: Francine A. Harkins; (302) 658-7017; [email protected] SICK CALLS: Anytime Bulletin Editor: [email protected] RECONCILIATION SERVICES: Bookkeeper: Laura G. Gibson 654-5565; Saturdays: 4 to 4:45 PM; Anytime by appointment [email protected] BAPTISMS: By appointment with at least one preparation session for new parents. DIRECTOR OF LITURGY & MUSIC WEDDINGS: Engaged couples wishing to marry in the Michael Marinelli (302) 777-5970 church should contact a Parish Priest at least one year DIRECTOR OF ADULT & YOUTH CHOIRS prior to the planned wedding date to begin the marriage Mary Ellen Schauber (302) 888-1556 preparation process. The year-long process includes ALTAR SERVER COORDINATOR diocesan pre-marriage classes and meetings with clergy. Steve Carroll (302) 373-6314 COMMUNION MINISTER COORDINATOR Carolyn Mostyn (610) 388-0829 COUNCIL #15436: Council LECTOR COORDINATOR meets on the third Tuesday of the month at 7:00 p.m., Harry Gordon (302) 994-8246 Archives Building. Membership in the Knights of Columbus PARISH COUNCIL EXECUTIVE OFFICER is open to men 18 years of age or older who are practicing Joseph Yacyshyn (302) 239-1879 Catholics. -

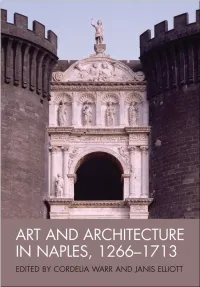

Art and Architecture in Naples, 1266-1713 / Edited by Cordelia Warr and Janis Elliott

This page intentionally left blank ART AND ARCHITECTURE IN NAPLES, 1266–1713 This page intentionally left blank ART AND ARCHITECTURE IN NAPLES, 1266–1713 NEW APPROACHES EDITED BY CORDELIA WARR AND JANIS ELLIOTT This edition first published 2010 r 2010 Association of Art Historians Originally published as Volume 31, Issue 4 of Art History Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley- Blackwell. Registered Office John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom Editorial Offices 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/ wiley-blackwell. The right of Cordelia Warr and Janis Elliott to be identified as the authors of the editorial material in this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. -

The Holy See

The Holy See LETTER OF THE HOLY FATHER FRANCIS TO HIS HOLINESS BARTHOLOMEW I, ARCHBISHOP OF CONSTANTINOPLE, ACCOMPANYING THE GIFT OF SOME RELICS OF SAINT PETER To His Holiness Bartholomew Archbishop of Constantinople Ecumenical Patriarch Your Holiness, dear Brother, With deep affection and spiritual closeness, I send you my cordial good wishes of grace and peace in the love of the Risen Lord. In these past weeks, I have often thought of writing to you to explain more fully the gift of some fragments of the relics of the Apostle Peter that I presented to Your Holiness through the distinguished delegation from the Ecumenical Patriarchate led by Archbishop Job of Telmessos which took part in the patronal feast of the Church of Rome. Your Holiness knows well that the uninterrupted tradition of the Roman Church has always testified that the Apostle Peter, after his martyrdom in the Circus of Nero, was buried in the adjoining necropolis of the Vatican Hill. His tomb quickly became a place of pilgrimage for the faithful from every part of the Christian world. Later, the Emperor Constantine erected the Vatican Basilica dedicated to Saint Peter over the site of the tomb of the Apostle. In June 1939, immediately following his election, my predecessor Pope Pius XII decided to undertake excavations beneath the Vatican Basilica. The works led first to the discovery of the exact burial place of the Apostle and later, in 1952, to the discovery, under the high altar of the Basilica, of a funerary niche attached to a red wall dated to the year 150 and covered with precious graffiti, including one of fundamental importance which reads, in Greek, Πετρος ευι. -

Twenty-Four Italy, Rome, & Vatican City Historical Maps & Diagrams

Twenty-Four Italy, Rome, & Vatican City Historical Maps & Diagrams From the Roman Republic to the Present Compiled by James C. Hamilton for www.vaticanstamps.org (November 2019), version 2.0 This collection of maps is designed to provide information about the political and religious geography of Europe, Italy, Rome, and Vatican City from the era of the Roman Republic to the present day. The maps include the following: 1. Plan of the Ancient City of Rome with the Servian and Aurelian Walls and location of Mons Vaticanus (Vatican Hill). 2. Map of Roman Republic and Empire, 218 B.C and 117 A.D. 3. Europe during the reign of Emperor Augustus, 31 B.C. to 14 A.D. 4. Palestine at the time of Jesus, 4 B.C to 30 A.D. 5. Diocletian’s division of the Roman Empire (r. 284-305). 6. Roman Empire at the death of Constantine I (337). 7. European kingdoms at the death of Charlemagne (814). 8. Divisions of the Carolingian Emopire (843) and the Donation of Pepin (756). 9. Europe and the Mediterranean, ca. 1190 (High Middle Ages). 10. Central Europe and the Holy Roman Empire under the Hohenstauffen Dnyasty (1079-1265). 11. Map of Italy in ca. 1000 12. Map of the Crusader States, ca. 1135 13. Map of Medieval Cluniac and Cisterciam Monasteries. 14. Map of Renaissance Italy in 1494. 15. Map of religious divisions in Europe after the Reformation movements. 16. Map of Europe in 1648 after the Peace of Westphalia (end of the ‘wars of religion’). 17. Italy in 1796, era of the wars of the French Revolution and Napoleon 18. -

The Vatican City

The Vatican City Location The Vatican City, also called the State of the Vatican City or Vatican City State, is the smallest independent state in the world. Its territory consists of a small land enclosed area within the city of Rome, Italy. The coordinates for the state are 41°54’North and 21°27’East. It is located on Vatican Hill, which is in the northwest part of Rome. Its boundaries are mostly an imaginary border that extends along the outer edge of St. Peter’s Square where it touches Piazza Pio XII and Via Paolo VI. Geography The Vatican City is the smallest sovereign state in the world with 0.44 square kilometers, which is also 108.7 acres (about 0.55 times the size of New York State’s fairgrounds). The border is 3.2 kilometers long and the only surrounding country is Italy. It is a Mediterranean climate with mild, rainy winters from September to May and hot, dry summers from May to August. The elevation extremes are 19 m at its lowest point and 75 m at its highest point. The area is 100 percent urban, with absolutely no farmland, pastures, or woodland areas. The Vatican City is located on a hill, which today is known as Vatican Hill (Mons Vaticanus) named many years ago before the emergence of Christianity. History That part of Rome was originally supposed to remain uninhabited because the area was considered sacred. However, in 326 the first church, Constantine’s Basilica, was built over the tomb of St. Peter. It was after that when the area became more populated, but every building that was built was connected to St. -

THE LAST JUDGMENT in CHRISTIAN ICONOGRAPHY Alison Morgan Public Lecture Given in the University of Cambridge, 1987

THE LAST JUDGMENT IN CHRISTIAN ICONOGRAPHY Alison Morgan Public lecture given in the University of Cambridge, 1987 I gave this lecture many years ago as part of my doctoral research into the iconography of Dante’s Divine Comedy, using slides to illustrate the subject matter. Thanks to digital technology it is now possible to create an illustrated version. The text remains in the original lecture form – in other words full references are not given. Illustrations are in the public domain, and acknowledged where appropriate; some are my own photographs. If I were giving this lecture today I would want to include material from eastern Europe which was not readily accessible at the time. But I hope this may serve by way of an introduction to the subject. Alison Morgan, September 2019 www.alisonmorgan.co.uk A. INTRODUCTION 1. Christian belief concerning the Last Judgment The subject of this lecture is the representation of the Last Judgment in Christian iconography. I would like therefore to begin by reminding you what it is that Christians believe about the Last Judgment. Throughout the centuries people have turned to the Gospel of Matthew as their main authority concerning the end of time. In chapter 25 Matthew records these words spoken by Jesus on the Mount of Olives: ‘When the Son of Man comes in his glory, and all the angels with him, then he will sit on the throne of his glory. All the nations will be gathered before him, and he will separate people one from another as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats, and he will put the sheep at his right hand and the goats at the left.