Arxiv:1810.10561V1 [Math.DG]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

All That Math Portraits of Mathematicians As Young Researchers

Downloaded from orbit.dtu.dk on: Oct 06, 2021 All that Math Portraits of mathematicians as young researchers Hansen, Vagn Lundsgaard Published in: EMS Newsletter Publication date: 2012 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link back to DTU Orbit Citation (APA): Hansen, V. L. (2012). All that Math: Portraits of mathematicians as young researchers. EMS Newsletter, (85), 61-62. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. NEWSLETTER OF THE EUROPEAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Editorial Obituary Feature Interview 6ecm Marco Brunella Alan Turing’s Centenary Endre Szemerédi p. 4 p. 29 p. 32 p. 39 September 2012 Issue 85 ISSN 1027-488X S E European M M Mathematical E S Society Applied Mathematics Journals from Cambridge journals.cambridge.org/pem journals.cambridge.org/ejm journals.cambridge.org/psp journals.cambridge.org/flm journals.cambridge.org/anz journals.cambridge.org/pes journals.cambridge.org/prm journals.cambridge.org/anu journals.cambridge.org/mtk Receive a free trial to the latest issue of each of our mathematics journals at journals.cambridge.org/maths Cambridge Press Applied Maths Advert_AW.indd 1 30/07/2012 12:11 Contents Editorial Team Editors-in-Chief Jorge Buescu (2009–2012) European (Book Reviews) Vicente Muñoz (2005–2012) Dep. -

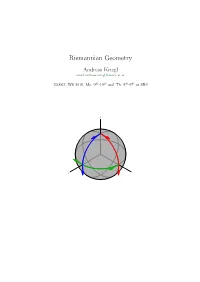

Riemannian Geometry Andreas Kriegl Email:[email protected]

Riemannian Geometry Andreas Kriegl email:[email protected] 250067, WS 2018, Mo. 945-1030 and Th. 900-945 at SR9 z y x This is preliminary english version of the script for my homonymous lecture course in the Winter Semester 2018. It was translated from the german original using a pre and post processor (written by myself) for google translate. Due to the limitations of google translate { see the following article by Douglas Hofstadter www.theatlantic.com/. /551570 { heavy corrections by hand had to be done af- terwards. However, it is still a rather rough translation which I will try to improve during the semester. It consists of selected parts of the much more comprehensive differential geometry script (in german), which is also available as a PDF file under http://www.mat.univie.ac.at/∼kriegl/Skripten/diffgeom.pdf. In choosing the content, I followed the curricula, so the following topics should be considered: • Levi-Civita connection • Geodesics • Completeness • Hopf-Rhinov theoroem • Selected further topics from Riemannian geometry. Prerequisite is the lecture course 'Analysis on Manifolds'. The structure of the script is thus the following: Chapter I deals with isometries and conformal mappings as well as Riemann sur- faces - i.e. 2-dimensional Riemannian manifolds - and their relation to complex analysis. In Chapter II we look again at differential forms in the context of Riemannian manifolds, in particular the gradient, divergence, the Hodge star operator, and most importantly, the Laplace Beltrami operator. As a possible first application, a section on classical mechanics is included. In Chapter III we first develop the concept of curvature for plane curves and space curves, then for hypersurfaces, and finally for Riemannian manifolds. -

EMS Newsletter September 2012 1 EMS Agenda EMS Executive Committee EMS Agenda

NEWSLETTER OF THE EUROPEAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Editorial Obituary Feature Interview 6ecm Marco Brunella Alan Turing’s Centenary Endre Szemerédi p. 4 p. 29 p. 32 p. 39 September 2012 Issue 85 ISSN 1027-488X S E European M M Mathematical E S Society Applied Mathematics Journals from Cambridge journals.cambridge.org/pem journals.cambridge.org/ejm journals.cambridge.org/psp journals.cambridge.org/flm journals.cambridge.org/anz journals.cambridge.org/pes journals.cambridge.org/prm journals.cambridge.org/anu journals.cambridge.org/mtk Receive a free trial to the latest issue of each of our mathematics journals at journals.cambridge.org/maths Cambridge Press Applied Maths Advert_AW.indd 1 30/07/2012 12:11 Contents Editorial Team Editors-in-Chief Jorge Buescu (2009–2012) European (Book Reviews) Vicente Muñoz (2005–2012) Dep. Matemática, Faculdade Facultad de Matematicas de Ciências, Edifício C6, Universidad Complutense Piso 2 Campo Grande Mathematical de Madrid 1749-006 Lisboa, Portugal e-mail: [email protected] Plaza de Ciencias 3, 28040 Madrid, Spain Eva-Maria Feichtner e-mail: [email protected] (2012–2015) Society Department of Mathematics Lucia Di Vizio (2012–2016) Université de Versailles- University of Bremen St Quentin 28359 Bremen, Germany e-mail: [email protected] Laboratoire de Mathématiques Newsletter No. 85, September 2012 45 avenue des États-Unis Eva Miranda (2010–2013) 78035 Versailles cedex, France Departament de Matemàtica e-mail: [email protected] Aplicada I EMS Agenda .......................................................................................................................................................... 2 EPSEB, Edifici P Editorial – S. Jackowski ........................................................................................................................... 3 Associate Editors Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya Opening Ceremony of the 6ECM – M. -

![CS 468 [2Ex] Differential Geometry for Computer Science](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1899/cs-468-2ex-differential-geometry-for-computer-science-2461899.webp)

CS 468 [2Ex] Differential Geometry for Computer Science

CS 468 Differential Geometry for Computer Science Lecture 19 | Conformal Geometry Outline • Conformal maps • Complex manifolds • Conformal parametrization • Uniformization Theorem • Conformal equivalence Conformal Maps Idea: Shapes are rarely isometric. Is there a weaker condition that is more common? Conformal Maps • Let S1; S2 be surfaces with metrics g1; g2. • A conformal map preserves angles but can change lengths. • I.e. φ : S1 ! S2 is conformal if 9 function u : S1 ! R s.t. g2(Dφp(X ); Dφp(Y )) = 2u(p) e g1(X ; Y ) for all X ; Y 2 TpS1 [Gu 2008] Isothermal Coordinates Fact: Conformality is very flexible. Theorem: Let S be a surface. For every p 2 S there exists an isothermal parametrization for a neighbourhood of p. 2 • This means that there exists U ⊆ R and V ⊆ S containing p, a map φ : U!V and a function u : U! R so that e2u(x) 0 g := [Dφ ]>Dφ = 8 x 2 U x x 0 e2u(x) • This is proved by solving a fully determined PDE. Corollary: Every surface is locally conformally planar. Corollary: Any pair of surfaces is locally conformally equivalent. A Connection to Complex Analysis The existence of isothermal parameters can be re-phrased in the language of complex analysis. 2 • Replace R with C. • Now every p 2 S has a neighbourhood that is holomorphic to a neighboorhood of C. • Thep fact that the metric is isothermal is key | multiplication by −1 in C is equivalent to rotation by π=2 in S. • S becomes a complex manifold. Fact: The connection to complex analysis is very deep! The Uniformization Theorem What happens globally? Uniformization Theorem: Let S be a 2D compact abstract surface with metric g. -

The Hodge Star Operator and the Beltrami Equation 11

THE HODGE STAR OPERATOR AND THE BELTRAMI EQUATION EDEN PRYWES Abstract. An essentially unique homeomorphic solution to the Beltrami equation was found in the 1960s using the theory of Calder´on-Zygmund and singular integral operators in Lp(C). We will present an alternative method to solve the Beltrami equation using the Hodge star operator and standard elliptic PDE theory. We will also discuss a different method to prove the regularity of the solution. This approach is partially based on work by Dittmar [5]. 1. Introduction A quasiconformal map is an orientation-preserving homeomorphism f : C → C, such that f ∈ 1,2 C Wloc ( ) and there exists K ≥ 1 with 2 |Df(z)| ≤ KJf (z) for a.e. z ∈ C. Here, Df is the derivative of f and Jf is the Jacobian of f. The above equation can be rewritten as |∂z¯f|≤ k|∂zf| where k < 1. In other words, f solves the following differential equation, often called the Beltrami Equation, (1.1) ∂z¯f = µ∂zf, ∞ with µ ∈ L (C) and kµk∞ ≤ k. The main goal of this paper is to prove the following theorem. Theorem 1.1. Let µ: C → C be measurable with compact support, kµk∞ = k < 1. Then there 1,2 exists an orientation-preserving homeomorphism Φ: C → C such that Φ ∈ Wloc (C) and Φ solves (1.1) a.e. Additionally, the map Φ can be chosen so that Φ(0) = 0 and Φ(1) = 1. In this case it is unique. arXiv:1801.08109v1 [math.AP] 24 Jan 2018 This theorem will follow from Theorem 3.1 which proves the same conclusions with the stronger assumption that µ is C∞-smooth. -

Notes on Conformal Geometry, Uniformization, and Ricci Flow

Notes on conformal geometry, uniformization, and Ricci flow Spencer Dembner 14 June, 2020 1 Introduction In this paper, we explain some of the connections between Riemann surfaces and 2-dimensional Riemannian manifolds. As long as we assume orientability, the two concepts are very nearly the same: a Riemann surface is just an oriented Riemannian surface whose metric is defined only up to rescaling (a \conformal manifold"). This allows us to translate between complex analytic statements about Riemann surfaces and geometric statements about Riemannian manifolds. The most important result about Riemann surfaces is the uniformization theorem, which says that the only simply connected Riemann surfaces are the disk, the complex plane, and the Riemann sphere. In the rest of the paper, we focus on interpreting this result in the language of Riemannian geometry. First, we show that uniformization is equivalent to a more explicitly geometric condition: Any 2-dimensional Riemannian manifold admits a unique constant curvature metric conformal to its original metric. Finally, we discuss a strategy, due to Hamilton and others, to prove certain cases of the uniformization theorem using Ricci flow. Our discussion here falls very short of a proof, but highlights some of the key technical points, and offers further references for the interested reader. Throughout the paper, all manifolds are taken to be smooth. Additionally, we will require that Riemann surfaces be smooth manifolds in the usual sense. In particular, the fact that all Riemann surfaces are second-countable is part of our definition. 2 Complex structure and isothermal coordinates The first thing we need to understand is the relationship between Riemannian structure and complex structure. -

![Arxiv:1711.01755V1 [Math.HO] 6 Nov 2017 Obyn H Ahmtcladpyia Etn,Adte a N a Had They Infinitely and the Setting, Physical and Philosophy](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9702/arxiv-1711-01755v1-math-ho-6-nov-2017-obyn-h-ahmtcladpyia-etn-adte-a-n-a-had-they-in-nitely-and-the-setting-physical-and-philosophy-5029702.webp)

Arxiv:1711.01755V1 [Math.HO] 6 Nov 2017 Obyn H Ahmtcladpyia Etn,Adte a N a Had They Infinitely and the Setting, Physical and Philosophy

PHYSICS IN RIEMANN’S MATHEMATICAL PAPERS ATHANASE PAPADOPOULOS Abstract. Riemann’s mathematical papers contain many ideas that arise from physics, and some of them are motivated by problems from physics. In fact, it is not easy to separate Riemann’s ideas in mathematics from those in physics. Furthermore, Riemann’s philosophical ideas are often in the back- ground of his work on science. The aim of this chapter is to give an overview of Riemann’s mathematical results based on physical reasoning or motivated by physics. We also elaborate on the relation with philosophy. While we discuss some of Riemann’s philo- sophical points of view, we review some ideas on the same subjects emitted by Riemann’s predecessors, and in particular Greek philosophers, mainly the pre-socratics and Aristotle. AMS Mathematics Subject Classification: 01-02, 01A55, 01A67. Keywords: Bernhard Riemann, space, Riemannian geometry, Riemann sur- face, trigonometric series, electricity, physics. Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Function theory and Riemann surfaces 11 3. Riemann’s memoir on trigonometric series 20 4. Riemann’s Habilitationsvortrag 1854 – Space and Matter 27 5. The Commentatio and the Gleichgewicht der Electricit¨at 37 6. Riemann’s other papers 39 7. Conclusion 42 References 43 1. Introduction Bernhard Riemann is one of these pre-eminent scientists who considered math- ematics, physics and philosophy as a single subject, whose objective is part of a arXiv:1711.01755v1 [math.HO] 6 Nov 2017 continuous quest for understanding the world. His writings not only are the basis of some of the most fundamental mathematical theories that continue to grow today, but they also effected a profound transformation of our knowledge of nature, in particular through the physical developments to which they gave rise, in mechan- ics, electromagnetism, heat, electricity, acoustics, and other topics. -

A Study of Particular Coordinate Systems

A STUDY OF PARTICULAR COORDINATE SYSTEMS A Thesis by Jennifer D. Ragan Bachelor of Science, Elon University, 2005 Submitted to the Department of Mathematics and Statistics and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science May 2011 c Copyright 2011 by Jennifer D. Ragan All Rights Reserved A STUDY OF PARTICULAR COORDINATE SYSTEMS The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this thesis for form and content, and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Science with a major in Applied Mathematics. Kirk Lancaster, Committee Chair Thalia Jeffres, Committee Member Elizabeth Behrman, Committee Member iii DEDICATION To my husband, parents, sister, and my wonderful family and friends iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I want to thank my thesis advisor Dr. Kirk Lancaster for his time, encouragement, and patience. Without Dr. Lancaster's support, enthusiasm and guidance this thesis would not of been possible. I want to thank Dr. Jeffres for her time and contributions that she provided as I was revising. I am grateful to Dr. Behrman for all her support and flexibility. I want to give a special thank you to Dr. Christopher Earles, Dr. Zhiren Jin and Dr. Diana Palenz for the time that they kindly gave to this thesis. Lastly, a big thank you to all my family and friends for their constant support and love. v ABSTRACT This thesis is a study of the properties and relationships between isothermal, har- monic and characteristic coordinate systems. -

Differential Geometry

Di®erential Geometry Michael E. Taylor 1 2 Contents The Basic Object 1. Surfaces, Riemannian metrics, and geodesics Vector Fields and Di®erential Forms 2. Flows and vector ¯elds 3. Lie brackets 4. Integration on Riemannian manifolds 5. Di®erential forms 6. Products and exterior derivatives of forms 7. The general Stokes formula 8. The classical Gauss, Green, and Stokes formulas 8B. Symbols, and a more general Green-Stokes formula 9. Topological applications of di®erential forms 10. Critical points and index of a vector ¯eld Geodesics, Covariant Derivatives, and Curvature 11. Geodesics on Riemannian manifolds 12. The covariant derivative and divergence of tensor ¯elds 13. Covariant derivatives and curvature on general vector bundles 14. Second covariant derivatives and covariant-exterior derivatives 15. The curvature tensor of a Riemannian manifold 16. Geometry of submanifolds and subbundles The Gauss-Bonnet Theorem and Characteristic Classes 17. The Gauss-Bonnet theorem for surfaces 18. The principal bundle picture 19. The Chern-Weil construction 20. The Chern-Gauss-Bonnet theorem Hodge Theory 21. The Hodge Laplacian on k-forms 22. The Hodge decomposition and harmonic forms 23. The Hodge decomposition on manifolds with boundary 24. The Mayer-Vietoris sequence for deRham cohomology 3 Spinors 25. Operators of Dirac type 26. Cli®ord algebras 27. Spinors 28. Weitzenbock formulas Minimal Surfaces 29. Minimal surfaces 30. Second variation of area 31. The Minimal surface equation Appendices A. Metric spaces, compactness, and all that B. Topological spaces C. The derivative D. Inverse function and implicit function theorem E. Manifolds F. Vector bundles G. Fundamental existence theorem for ODE H. -

How to Construct Integrating Factors Applications to the Isothermal Parameterization of Surfaces

How to Construct Integrating Factors Applications to the Isothermal Parameterization of Surfaces Nicholas Wheeler March 2016 Introduction. This short essay has been motivated by a problem encountered in Eisenhart’s discussion1 of the transformation from arbitrary to “isometric” (or “isothermal/isothermic” in a terminology apparently due ( 1837) to Lam´e) parameterizations of surfaces in 3-space. I borrow from page∼ 26 of my old Mathematical Thermodynamics class notes (1967) and from related material that appears on page 19 , Chapter I of my Thermal Physics notes ( 2002). ∼ The construction procedure, and examples. Let d–F = X(x, y)dx + Y (x, y)dy be an inexact differential form: ∂X/∂ = ∂Y/∂x. Look to the Pfaffian differential equation " d–F = 0 which can be written dy X(x, y) = f(x, y) dx −Y (x, y) ≡ The equations f(x, y) = c : c constant inscribe on the x, y -plane a c-parameterized family of curves. On any such curve we have { } df ∂f ∂f dy = + = dc = 0 dx ∂x ∂y dx dx whence ∂f ∂f dy ∂f ∂f + = X = 0 ∂x ∂y dx ∂x − ∂y Y giving ∂f ∂f Y = X χ(x, y)XY ∂x ∂y ≡ With χ thus defined we have ∂f ∂f = χX and = χY ∂x ∂y 1 Treatise on the Differential Geometry of Curves and Surfaces (1909), 40. § 2 How to construct integrating factors giving ∂f ∂f χ = 1 = 1 X ∂x Y ∂y and ∂f ∂f χd–F = dx + dy = df ∂x ∂y So though d–F is inexact, χd–F = df is an exact differential form—rendered exact by the “integrating factor” χ(x, y). -

Conformal Harmonic Coordinates

CONFORMAL HARMONIC COORDINATES MATTI LASSAS AND TONY LIIMATAINEN Abstract. We study conformal harmonic coordinates on Riemannian manifolds. These are coordinates constructed as quotients of solutions to the conformal Laplace equation. We show their existence under gen- eral conditions. We find that conformal harmonic coordinates are a close conformal analogue of harmonic coordinates. We prove up to boundary regularity results for conformal mappings. We show that Weyl, Cot- ton, Bach, and Fefferman-Graham obstruction tensors become elliptic operators in conformal harmonic coordinates if one normalizes the de- terminant of the metric. We give a corresponding elliptic regularity result, which includes an analytic case. We prove a unique continu- ation result for local conformal flatness for Bach and obstruction flat manifolds. We discuss and prove existence of conformal harmonic coor- dinates on Lorentzian manifolds. We prove unique continuation results for conformal mappings both on Riemannian and Lorentzian manifolds. 1. Introduction In this article we study a coordinate system called conformal harmonic co- ordinates on Riemannian manifolds. Conformal harmonic coordinates were invented in a recent joint paper [LLS16] by the authors. These coordinates are conformally invariant and they have similar properties to harmonic co- ordinates. One of the main motivations of this paper is to better understand these coordinates. This is done by proving new results in conformal geom- etry and by giving new proofs of some earlier results. The results concern conformal mappings and conformal curvature tensors such as Weyl and Bach tensors. We prove the existence and regularity of conformal harmonic co- ordinates and characterize them. We also initiate the study of conformal harmonic coordinates on Lorentzian manifolds. -

![Arxiv:1308.3325V4 [Math.DG] 17 Jan 2016 References 43](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5585/arxiv-1308-3325v4-math-dg-17-jan-2016-references-43-6275585.webp)

Arxiv:1308.3325V4 [Math.DG] 17 Jan 2016 References 43

LECTURES ON MINIMAL SURFACE THEORY BRIAN WHITE Contents Introduction 2 1. The First Variation Formula and Consequences 3 Monotonicity 6 Density at infinity 7 Extended monotonicity 8 The isoperimetric inequality 12 2. Two-Dimensional Minimal Surfaces 13 Relation to harmonic maps 13 Conformality of the Gauss map 14 Total curvature 15 The Weierstrass Representation 17 The geometric meaning of the Weierstrass data 20 Rigidity and Flexibility 21 3. Curvature Estimates and Compactness Theorems 23 The 4π curvature estimate 25 A general principle about curvature estimates 26 An easy version of Allard's Regularity Theorem 26 Bounded total curvatures 27 Stability 29 4. Existence and Regularity of Least-Area Surfaces 33 Boundary regularity 38 Branch points 38 The theorems of Gulliver and Osserman 39 Higher genus surfaces 39 What happens as the genus increases? 41 Embeddedness: The Meeks-Yau Theorem 42 arXiv:1308.3325v4 [math.DG] 17 Jan 2016 References 43 Date: August 1, 2013. Revised January 16, 2016. 2000 Mathematics Subject Classification. Primary: 53A10; Secondary: 49Q05, 53C42. The author was partially funded by NSF grants DMS{1105330 and DMS{1404282. 1 2 BRIAN WHITE Introduction Minimal surfaces have been studied by mathematicians for several centuries, and they continue to be a very active area of research. Minimal surfaces have also proved to be a useful tool in other areas, such as in the Willmore problem and in general relativity. Furthermore, various general techniques in geometric analysis were first discovered in the study of minimal surfaces. The following notes are slightly expanded versions of four lectures presented at the 2013 summer program of the Institute for Advanced Study and the Park City Mathematics Institute.