Learning to Change, Changing to Learn : Managing Natural Resources For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

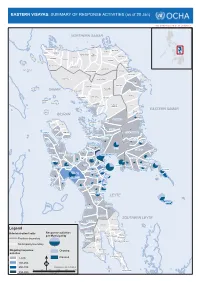

EASTERN VISAYAS: SUMMARY of REHABILITATION ACTIVITIES (As of 24 Mar)

EASTERN VISAYAS: SUMMARY OF REHABILITATION ACTIVITIES (as of 24 Mar) Map_OCHA_Region VIII_01_3W_REHAB_24032014_v1 BIRI PALAPAG LAVEZARES SAN JOSE ALLEN ROSARIO BOBON MONDRAGON LAOANG VICTORIA SAN CATARMAN ROQUE MAPANAS CAPUL SAN CATUBIG ANTONIO PAMBUJAN GAMAY N O R T H E R N S A M A R LAPINIG SAN SAN ISIDRO VICENTE LOPE DE VEGA LAS NAVAS SILVINO LOBOS JIPAPAD ARTECHE SAN POLICARPIO CALBAYOG CITY MATUGUINAO MASLOG ORAS SANTA GANDARA TAGAPUL-AN MARGARITA DOLORES SAN JOSE DE BUAN SAN JORGE CAN-AVID PAGSANGHAN MOTIONG ALMAGRO TARANGNAN SANTO PARANAS NI-O (WRIGHT) TAFT CITY OF JIABONG CATBALOGAN SULAT MARIPIPI W E S T E R N S A M A R B I L I R A N SAN JULIAN KAWAYAN SAN SEBASTIAN ZUMARRAGA HINABANGAN CULABA ALMERIA CALBIGA E A S T E R N S A M A R NAVAL DARAM CITY OF BORONGAN CAIBIRAN PINABACDAO BILIRAN TALALORA VILLAREAL CALUBIAN CABUCGAYAN SANTA RITA BALANGKAYAN MAYDOLONG SAN BABATNGON ISIDRO BASEY BARUGO LLORENTE LEYTE SAN HERNANI TABANGO MIGUEL CAPOOCAN ALANGALANG MARABUT BALANGIGA TACLOBAN GENERAL TUNGA VILLABA CITY MACARTHUR CARIGARA SALCEDO SANTA LAWAAN QUINAPONDAN MATAG-OB KANANGA JARO FE PALO TANAUAN PASTRANA ORMOC CITY GIPORLOS PALOMPON MERCEDES DAGAMI TABONTABON JULITA TOLOSA GUIUAN ISABEL MERIDA BURAUEN DULAG ALBUERA LA PAZ MAYORGA L E Y T E MACARTHUR JAVIER (BUGHO) CITY OF BAYBAY ABUYOG MAHAPLAG INOPACAN SILAGO HINDANG SOGOD Legend HINUNANGAN HILONGOS BONTOC Response activities LIBAGON Administrative limits HINUNDAYAN BATO per Municipality SAINT BERNARD ANAHAWAN Province boundary MATALOM SAN JUAN TOMAS (CABALIAN) OPPUS Municipality boundary MALITBOG S O U T H E R N L E Y T E Ongoing rehabilitation Ongoing MAASIN CITY activites LILOAN MACROHON PADRE BURGOS SAN 1-30 Planned FRANCISCO SAN 30-60 RICARDO LIMASAWA PINTUYAN 60-90 Data sources:OCHA,Clusters 0 325 K650 975 1,300 1,625 90-121 Kilometers EASTERN VISAYAS:SUMMARY OF REHABILITATION ACTIVITIES AS OF 24th Mar 2014 Early Food Sec. -

Bridges Across Oceans: Initial Impact Assessment of the Philippines Nautical Highway System and Lessons for Southeast Asia

Bridges across Oceans Initial Impact Assessment of the Philippines Nautical Highway System and Lessons for Southeast Asia April 2010 0 2010 Asian Development Bank All rights reserved. Published 2010. Printed in the Philippines ISBN 978-971-561-896-0 Publication Stock No. RPT101731 Cataloging-In-Publication Data Bridges across Oceans: Initial Impact Assessment of the Philippines Nautical Highway System and Lessons for Southeast Asia. Mandaluyong City, Philippines: Asian Development Bank, 2010. 1. Transport Infrastructure. 2. Southeast Asia. I. Asian Development Bank. The views expressed in this book are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent. ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “country” in this document, ADB does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. ADB encourages printing or copying information exclusively for personal and noncommercial use with proper acknowledgment of ADB. Users are restricted from reselling, redistributing, or creating derivative works for commercial purposes without the express, written consent of ADB. Note: In this report, “$” refers to US dollars. 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel +63 2 632 -

(Intermittent Sections) (B00018LT), Daang Maharlika Leyte - Samar

Contract ID No.: 21I00093 Contract Name: Repair/Maintenance of San Juanico Bridge – Approach and Concrete Deck (Intermittent Sections) (B00018LT), Daang Maharlika Leyte - Samar Location of the Project: Daang Maharlika Leyte - Samar Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS REGIONAL OFFICE VIII Baras, Palo, Leyte BIDDING DOCUMENTS F OR Procurement / Contract ID: 21I00093 Contract Name: Repair/Maintenance of San Juanico Bridge – Approach and Concrete Deck (Intermittent Sections) (B00018LT), Daang Maharlika Leyte - Samar Contract Location: Daang Maharlika Leyte - Samar Deadline of Receipt/Submission of Bids: July 13, 2021 (1:00 P.M.) Date of Opening of Bids : July 13, 2021 (1:00 P.M.) Start Date for Issuance of Bidding Documents : June 22, 2021 – July 13, 2021 – December 2 2, 2020, 2020 Prepared by: Checked/Reviewed: MAINTENANCE DIVISION ANGELITA C. OBEDIENCIA End User/Implementing Office Head, BAC-TWG NOTED:A L. TALDE Chief Administrative Officer Bidding Documents to be posted in BAC Chairperson No. of Pages: 78 the DPWH & PhilGEPS Websites on: December 2, 2020 Prepared by: Checked/Reviewed: ANGELITA C. OBEDIENCIA Head, BAC-TWG 1 Contract ID No.: 21I00093 Contract Name: Repair/Maintenance of San Juanico Bridge – Approach and Concrete Deck (Intermittent Sections) (B00018LT), Daang Maharlika Leyte - Samar Location of the Project: Daang Maharlika Leyte - Samar TABLE OF CONTENTS Glossary of Terms, Abbreviations and 4 Acronyms……………………..……………………………………………………............... Section I - Invitation to Bid (IB) …………………………………………………... .. 6 Section II - Instructions to Bidders (ITB) …………………………………………….. 7 1. Scope of Bid……………………………………………………………………………. 11 2. Funding Information………………………………………………………………….. 11 3. Bidding Requirements………………………………………………………………… 11 4. Corrupt, Fraudulent, Collusive, Coercive, and Obstructive Practices……………. 11 5. Eligible Bidders……………………………………………………………………...... 11 6. Origin of Associated Goods…………………………………………………………… 12 7.Subcontracts……………………………………………………………………………. -

The Project for Study on Improvement of Bridges Through Disaster Mitigating Measures for Large Scale Earthquakes in the Republic of the Philippines

THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS (DPWH) THE PROJECT FOR STUDY ON IMPROVEMENT OF BRIDGES THROUGH DISASTER MITIGATING MEASURES FOR LARGE SCALE EARTHQUAKES IN THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES FINAL REPORT MAIN TEXT [2/2] DECEMBER 2013 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) CTI ENGINEERING INTERNATIONAL CO., LTD CHODAI CO., LTD. NIPPON KOEI CO., LTD. EI JR(先) 13-261(3) Exchange Rate used in the Report is: PHP 1.00 = JPY 2.222 US$ 1.00 = JPY 97.229 = PHP 43.756 (Average Value in August 2013, Central Bank of the Philippines) LOCATION MAP OF STUDY BRIDGES (PACKAGE B : WITHIN METRO MANILA) i LOCATION MAP OF STUDY BRIDGES (PACKAGE C : OUTSIDE METRO MANILA) ii B01 Delpan Bridge B02 Jones Bridge B03 Mc Arthur Bridge B04 Quezon Bridge B05 Ayala Bridge B06 Nagtahan Bridge B07 Pandacan Bridge B08 Lambingan Bridge B09 Makati-Mandaluyong Bridge B10 Guadalupe Bridge Photos of Package B Bridges (1/2) iii B11 C-5 Bridge B12 Bambang Bridge B13-1 Vargas Bridge (1 & 2) B14 Rosario Bridge B15 Marcos Bridge B16 Marikina Bridge B17 San Jose Bridge Photos of Package B Bridges (2/2) iv C01 Badiwan Bridge C02 Buntun Bridge C03 Lucban Bridge C04 Magapit Bridge C05 Sicsican Bridge C06 Bamban Bridge C07 1st Mandaue-Mactan Bridge C08 Marcelo Fernan Bridge C09 Palanit Bridge C10 Jibatang Bridge Photos of Package C Bridges (1/2) v C11 Mawo Bridge C12 Biliran Bridge C13 San Juanico Bridge C14 Lilo-an Bridge C15 Wawa Bridge C16 2nd Magsaysay Bridge Photos of Package C Bridges (2/2) vi vii Perspective View of Lambingan Bridge (1/2) viii Perspective View of Lambingan Bridge (2/2) ix Perspective View of Guadalupe Bridge x Perspective View of Palanit Bridge xi Perspective View of Mawo Bridge (1/2) xii Perspective View of Mawo Bridge (2/2) xiii Perspective View of Wawa Bridge TABLE OF CONTENTS Location Map Photos Perspective View Table of Contents List of Figures & Tables Abbreviations Main Text Appendices MAIN TEXT PART 1 GENERAL CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................... -

F866e63db19145e7492573f70

Sitrep No. 3 Tab A EFFECTS OF FLOODING AND LANDSLIDE AFFECTED POPULATION As of February 22, 2008, 8:00 AM AFFECTED POPULATION No. of Evac DISPLACED POPULATION PROVINCE / CITY / REGION Centers Inside Evac Center Outside Evac Center MUNICIPALITY Brgys Families Persons Established Families Persons Families Persons GRAND TOTAL 896 106,455 514,862 7 96 515 60,558 294,882 IV-B 38 7,113 38,192 1 3 12 800 4,800 Oriental Mindoro 38 7,113 38,192 1 3 12 800 4,800 Baco 14 2,243 8,972 Naujan 24 4,870 29,220 1 3 12 800 4,800 V 021,35081,63800000 Albay 9,839 51,162 Catanduanes 150 650 Sorsogon 51 235 Camarines Sur 11,187 28,853 Camarines Norte 123 738 VI 98 3,043 14,757 2 17 45 0 0 Capiz 98 3,043 14,757 2 17 45 Cuartero 8 Dao 12 575 3,420 Dumalag 2 Dumarao 4 120 620 Maayon 15 340 2,040 Mambusao 3 Panay 4 59 353 Panitan 20 100 600 Pontevedra 15 1,059 3,774 1 15 33 Sigma 15 790 3,950 1 2 12 VIII 738 73,302 372,266 1 19 56 58,502 283,802 Eastern Samar 360 33,036 164,716 0 0 0 29,079 144,840 Arteche 13 1,068 5,340 1,068 5,340 Balangiga 13 1,184 5,920 5 17 Balangkayan 10 573 2,267 451 2,183 Borongan 30 1,376 6,582 1,314 6,328 Can-avid 14 1,678 8,411 1,678 8,411 Dolores 27 4,050 20,250 4,050 20,450 Gen. -

Region 8 Households Under 4Ps Sorsogon Biri 950

Philippines: Region 8 Households under 4Ps Sorsogon Biri 950 Lavezares Laoang Palapag Allen 2174 Rosario San Jose 5259 2271 1519 811 1330 San Roque Pambujan Mapanas Victoria Capul 1459 1407 960 1029 Bobon Catarman 909 San Antonio Mondragon Catubig 1946 5978 630 2533 1828 Gamay San Isidro Northern Samar 2112 2308 Lapinig Lope de Vega Las Navas Silvino Lobos 2555 Jipapad 602 San Vicente 844 778 595 992 Arteche 1374 San Policarpo Matuguinao 1135 Calbayog City 853 Oras 11265 2594 Maslog Calbayog Gandara Dolores ! 2804 470 Tagapul-An Santa Margarita San Jose de Buan 2822 729 1934 724 Pagsanghan San Jorge Can-Avid 673 1350 1367 Almagro Tarangnan 788 Santo Nino 2224 1162 Motiong Paranas Taft 1252 2022 Catbalogan City Jiabong 1150 4822 1250 Sulat Maripipi Samar 876 283 San Julian Hinabangan 807 Kawayan San Sebastian 975 822 Culaba 660 659 Zumarraga Almeria Daram 1624 Eastern Samar 486 Biliran 3934 Calbiga Borongan City Naval Caibiran 1639 2790 1821 1056 Villareal Pinabacdao Biliran Cabucgayan Talalora 2454 1433 Calubian 588 951 746 2269 Santa Rita Maydolong 3070 784 Basey Balangkayan Babatngon 3858 617 1923 Leyte Llorente San Miguel Hernani Tabango 3158 Barugo 1411 1542 595 2404 1905 Tacloban City! General Macarthur Capoocan Tunga 7531 Carigara 1056 2476 367 2966 Alangalang Marabut Lawaan Balangiga Villaba 3668 Santa Fe Quinapondan 1508 1271 800 895 2718 Kananga Jaro 997 Salcedo 2987 2548 Palo 1299 Pastrana Giporlos Matag-Ob 2723 1511 902 1180 Leyte Tanauan Mercedes Ormoc City Dagami 2777 326 Palompon 6942 2184 Tolosa 1984 931 Julita Burauen 1091 -

LSDE February 27, 2021

Leyte-Samar DAILYPOSITIVE EXPRESS l FAIR l FREE VOL. XXXI II NO. 019 SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 27, 2021 P15.00 IN TACLOBAN Considered as an ‘isolated case’ DA confirms ASF RONALDin O. REYES / JOEYTacloban A. GABIETA City TACLOBAN CITY-The African Swine Fever (ASF) has now reached this city as the Depart- ment of Agriculture (DA) confirmed this to Mayor Alfred Romualdez on Wednesday (Feb. 24) with the first case involving a sow owned by a private raiser in Barangay 84. With the confirmation CVO, said in a phone inter- of the ASF in the city, May- view. or Romualdez has issued According to Alcantara, an order to the City Vet- the first ASF case in the city erinary Office (CVO) to involved a backyard piggery intensify their campaign in Brgy.84. TOURISM REOPENING. After almost a year now, the munici- and surveillance to ensure Alcantara said that the ASF IN TACLOBAN. Though it is still considered as an ‘isolated pality of Padre Burgos in Southern Leyte has reopened its div- that the disease would not owner reported that her case, ‘the Department of Agriculture confirms the existence of ing sites to tourists who, however, has to follow the mandatory spread and affect other sow developed fever and African Swine Fever (ASF) in Tacloban City. Mayor Alfred Ro- health protocols. (Photo SOGOD BAY SCUBA RESORT) hogs in the city, Dr. Eu- mualdez has directed for a stricter border control and monitoring nice Alcantara, head of the see DA /page 17... to ensure ASF will not spread to other villages in the city. -

EASTERN VISAYAS: SUMMARY of RESPONSE ACTIVITIES (As of 20 Jan)

EASTERN VISAYAS: SUMMARY OF RESPONSE ACTIVITIES (as of 20 Jan) Map_OCHA_Region VIII_01_3W_20142001_v1 BIRI NORTHERN SAMAR PAMBUJAN LAVEZARES SAN JOSE PALAPAG LAOANG ALLEN ROSARIO MONDRAGON SAN ROQUE MAPANAS CAPUL VICTORIA CATARMAN BOBON CATUBIG GAMAY SAN ANTONIO SAN ISIDRO LOPE DE VEGA LAPINIG LAS NAVAS SAN VICENTE SILVINO LOBOS JIPAPAD ARTECHE CALBAYOG CITY MATUGUINAO SAN POLICARPIO ORAS MASLOG GANDARA SAN JOSE TAGAPUL-AN DE BUAN DOLORES SAMAR SANTA MARGARITA CAN-AVID SAN JORGE PAGSANGHAN MOTIONG ALMAGRO SANTO NI-O TARANGNAN JIABONG PARANAS TAFT CITY OF CATBALOGAN (WRIGHT) SULAT EASTERN SAMAR MARIPIPI BILIRAN SAN JULIAN HINABANGAN SAN SEBASTIAN KAWAYAN ZUMARRAGA ALMERIA CULABA NAVAL DARAM CALBIGA CALUBIAN CAIBIRAN CITY OF BORONGAN VILLAREAL PINABACDAO TALALORA BILIRAN SANTA RITA CABUCGAYAN MAYDOLONG SAN BALANGKAYAN ISIDRO BABATNGON BASEY SAN LLORENTE BARUGO MIGUEL HERNANI LEYTE TABANGO CAPOOCAN TACLOBAN CITY ALANGALANG BALANGIGA GENERAL MACARTHUR TUNGA VILLABA SANTA CARIGARA FE SALCEDO JARO QUINAPONDAN PALO MARABUT LAWAAN MATAG-OB KANANGA PASTRANA MERCEDES GIPORLOS DAGAMI TANAUAN TOLOSA PALOMPON ORMOC CITY TABONTABON MERIDA DULAG JULITA ISABEL BURAUEN ALBUERA LA PAZ MAYORGA MACARTHUR LEYTE JAVIER (BUGHO) GUIUAN ABUYOG CITY OF BAYBAY MAHAPLAG SILAGO SOUTHERN LEYTE INOPACAN SOGOD HINDANG Legend HINUNANGAN HILONGOS BONTOC Response activities LIBAGON Administrative limits HINUNDAYAN per Municipality BATO SAINT BERNARD ANAHAWAN Province boundary TOMAS MATALOM OPPUS SAN JUAN (CABALIAN) Municipality boundary MAASIN CITY Ongoing response Ongoing MALITBOG LILOAN activites PADRE BURGOS MACROHON SAN FRANCISCO 1-100 Planned 100-250 PINTUYAN 250-350 Data sources:OCHA,Clusters LIMASAWA 0 340 K680 1,020 1,360 1,700 SAN RICARDO 350-450 Kilometers EASTERN VISAYAS:SUMMARY OF RESPONSE ACTIVITIES AS OF 20 th Jan 2014 Em. -

Chapter 4 Safety in the Philippines

Table of Contents Chapter 1 Philippine Regions ...................................................................................................................................... Chapter 2 Philippine Visa............................................................................................................................................. Chapter 3 Philippine Culture........................................................................................................................................ Chapter 4 Safety in the Philippines.............................................................................................................................. Chapter 5 Health & Wellness in the Philippines........................................................................................................... Chapter 6 Philippines Transportation........................................................................................................................... Chapter 7 Philippines Dating – Marriage..................................................................................................................... Chapter 8 Making a Living (Working & Investing) .................................................................................................... Chapter 9 Philippine Real Estate.................................................................................................................................. Chapter 10 Retiring in the Philippines........................................................................................................................... -

Geophysical Risks and Exposure of Public School Buildings in Samar

Journal of Academic Research 03:2(2018), pp. 14-28 Geophysical Risks and Exposure of Public School Buildings in Samar Rene B. Novilla Samar State University [email protected] Abstract: Hazards are everywhere, and people are expected to prepare for the eventuality that the hazard will turn into a disaster. By doing so, the impact of a disaster is reduced. One of the most important facilities during a disaster is evacuation halls (which include school buildings) next to hospitals. Schools are also areas where people congregate and therefore must be resilient to any disaster to minimize casualties. The study was conducted to determine the different geophysical risks in Samar are and what the level of exposure of its public school buildings. Based on secondary data from authorities, and computer-aided simulations such as REDAS and NOAH, the public schools of Samar are exposed to varied intensity of earthquakes which may come from the Philippine Fault Zone, the Philippine Trench and the numerous lineaments in and nearby Samar Island. The risk rating for rain-induced landslides is greater than earthquake-induced landslide. It was also found out that a tsunami in the area directly attributed to an earthquake is unlikely. Keywords: earthquake, tsunami, landslides, Western Samar, DRRM, moderate risk 1. Introduction followed by a 7.8 magnitude in China in 2008 (≈87,600 killed), and a magnitude of Greater casualties from natural 7.8 in Nepal in 2015 (≈9,000 killed). A hazards are caused by geophysical hazards devastating tsunami occurred about 8,000 (Rees et al., 2012). Earthquakes, volcanic years ago when a volcano had an avalanche activity including emissions, and related in Sicily estimated to have heights higher geophysical processes such as mass than a 10-story building (LiveScience, movements, landslides, rock slides, surface 2011). -

Office of the Executive Officer

Republic of the Philippines Judicial and Bar Council Manila Office of the Executive Officer Table 3. Second Execom Deliberation (January - December 2018) NO. OF NO. OF DATE OF MEETING COURT/OFFICE WHERE VACANT POSITIONS EXIST CONSIDERED CANDIDATES CANDIDATES 10 January 2018 COURT OF APPEALS - Associate Justice (vice Justice Leoncia R. 29 28 Dimagiba LEGAL EDUCATION BOARD - Regular Member representing the 4 4 Philippine Association of Law Schools LEGAL EDUCATION BOARD - Regular Member representing the 4 4 Philippine Association of Law Professors REGION III: RTC, Br. 91, Baler, Aurora 6 6 RTC, Br. 8, Malolos City, Bulacan 15 14 RTC, Br. 17, Malolos City, Bulacan 35 33 RTC, Br. 84, Malolos City, Bulacan 36 34 RTC, Br. 102, Malolos City, Bulacan 45 43 RTC, Br. 103, Malolos City, Bulacan 45 43 RTC, Br. 104, Malolos City, Bulacan 45 43 RTC, Br. 23, Cabanatuan City, Nueva Ecija 15 15 RTC, Br. 29, Cabanatuan City, Nueva Ecija 18 18 RTC, Br. 30, Cabanatuan City, Nueva Ecija 13 13 RTC, Br. 36, Gapan City, Nueva Ecija 13 13 RTC, Br. 61, Angeles City, Pampanga 35 33 RTC, Br. 114, Angeles City, Pampanga 45 45 RTC, Br. 115, Angeles City, Pampanga 45 45 RTC, Br. 116, Angeles City, Pampanga 45 45 RTC, Br. 117, Angeles City, Pampanga 45 45 RTC, Br. 118, Angeles City, Pampanga 45 45 RTC, Br. 109, Capas, Tarlac 21 21 RTC, Br. 105, Paniqui, Tarlac 23 23 RTC, Br. 106, Paniqui, Tarlac 23 23 RTC, Br. 110, Tarlac City 22 22 RTC, Br. 111, Tarlac City 22 22 RTC, Br. 112, Camiling, Tarlac 19 19 RTC, Br. -

Terminal Report – Csr Program, Leyte Leg

TERMINAL REPORT – CSR PROGRAM, LEYTE LEG I. PROJECT DETAILS NAME: Leyte Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) DATE: 26 – 29 June 2016 VENUE: Province of Leyte ATTENDEES: 1. Teresita D. Landan 12. Jonathan P. Bravo 2. Maryh Jane P. Mabagos 13. Abigail B. Francisco 3. Millisa M. Nuada 14. Cesar R. Villanueva 4. Jesamy D. Laurea 15. Jocelyn C. Casiano 5. Ma. Stefani Trixie E. Lago 16. Grace C. La Rosa 6. Krisandra A. Cheung 17. Janet G. Villafranca 7. Uhde L. Usual 18. Ricardo P. Cabansag 8. Arnold T. Gonzales 19. Annabelle F. Balboa 9. Irene U. Francisco 20. Jonathan Omar V. De Villa 10. Francine M. Roca 21. Jacqueline Arielle Ong 11. Nelia B. Ramos II. TPB CSR STATEMENT TPB is a responsible organization committed to marketing the Philippines as a world class travel destination. TPB takes initiative to engage creatively in programs, projects and activities that increase environmental awareness of all tourism stakeholders, resulting to greater respect for nature and deeper appreciation of local culture and heritage in TPB’s pursuit of Green and Sustainable Tourism. III. BACKGROUND TPB, in its commitment in pursuing green and sustainable tourism, included in the Corporation’s annual work program the conduct of CSR activities. These activities aim to create green and environment awareness; that shall result to a greater respect and a deeper appreciation of nature and Filipino culture and heritage; not only to its participants but also to tourism stakeholders and most importantly to future generations who will greatly benefit from these projects. In consideration of its manpower as well as the numerous programs, projects and activities being undertaken by the Corporation in fulfillment of its mandate, the CSR Program was designed to have multiple segments to warrant participation of most if not all of its employee while ensuring the smooth operation of the company.