Disaster Preparedness and Disaster Experience in French Polynesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zion in Paradise

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Faculty Honor Lectures Lectures 5-1-1959 Zion in Paradise S. George Ellsworth Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honor_lectures Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Ellsworth, S. George, "Zion in Paradise" (1959). Faculty Honor Lectures. Paper 24. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honor_lectures/24 This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by the Lectures at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Honor Lectures by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TWENTY-FIRST FACULTY HONOR LECTURE Zion • Paradise EARLY MORMONS IN THE SOUTH SEAS by S. GEORGE ELLSWORTH Associate Professor of History THE FACULTY ASSOCIATION UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY LOGAN UTAH 1959 CONTENTS page THE IDEA OF CONVERSION ............................................................ 3 THE EARLY EXPANSION OF MORMONISM ................................ 4 EARLY MORMONS IN THE SOUTH SEAS .................................... 6 From Nauvoo to Tubuai, 1843-1844 ................................................ 6 The English and the French in Tahiti ................. .. ....................... 7 The Mormons at Tahiti, 1844 ........................................................ 9 First stronghold on Tubuai, 1844-1845 ........................................ 10 From Tahiti . ....... .. ........ ..... ........ ........................................................ -

Ancient Magic and Religious Trends of the Rāhui on the Atoll of Anaa, Tuamotu Frédéric Torrente

2 Ancient magic and religious trends of the rāhui on the atoll of Anaa, Tuamotu Frédéric Torrente This paper is based on vernacular material that was obtained from one of the last of the ancient vanaga, masters of pre-Christian lore, Paea-a-Avehe, of Anaa1 Island. Introduction Throughout the last century, in the Tuamotuan archipelago, the technical term rāhui has been applied to ‘sectors’ (secteurs): specified areas where the intensive monoculture of the coconut tree was established, at that time and still today, according to the principle of letting these areas lie fallow between periods of cropping. The religious reasons for this method have been forgotten. The link between Christian conversion and the development of coconut plantations has changed the Tuamotuan atoll’s landscape through the introduction 1 Anaa is the Tahitian name of this atoll (‘Ana’a). In Tuamotuan language, it should be noted ‘Ganaa’ or ‘Ganaia’. This atoll is situated in western Tuamotu, in the Putahi or Parata linguistic area. 25 THE RAHUI of new modes of land occupation and resource management. In old Polynesia, the political and the religious were intertwined, as well as man and his symbolic and ritual environment. Political and social aspects are studied elsewhere in this book. This essay considers the religious and ritual picture of pre-European life on the islands, and shows how religious concepts influenced man in his environment. The Tuamotuan group of islands represents the greatest concentration of atolls worldwide; they are a unique, two-dimensional universe, close to water level and lacking environmental features, such as high ground, that could provide a place of refuge. -

Your Cruise Marquesas, the Tuamotus & Society Islands

Marquesas, The Tuamotus & Society Islands From 6/11/2021 From Papeete, Tahiti Island Ship: LE PAUL GAUGUIN to 20/11/2021 to Papeete, Tahiti Island From Tahiti, PAUL GAUGUIN Cruises invites you to embark on an all-new 15-day cruise to the heart of idyllic islands and atolls hemmed by stunning clear-water lagoons and surrounded by an exceptional coral reef. Aboard Le Paul Gauguin, set sail to discover French Polynesia, considered one of the most beautiful places in the world. Le Paul Gauguin will stop at the heart of the Tuamotu Islands to explore the marvellous depths of the atoll of Fakarava, a UNESCO-classified nature reserve. Discover the unique charms of Marquesasthe Islands. The singer- songwriter Jacques Brel sang about the Marquesas Islands and the painter Paul Gauguin was inspired by these islands which stand like dark green fortresses surrounded by the indigo blue of the Pacific. Here, you will find neither lagoons nor reefs. The archipelago’s charm lies in its wild beauty. In the heart of the dense forests of Nuku Hiva, droplets from the waterfalls dive off the vertiginous cliffs. As for the islands of Hiva Oa and Fatu Hiva, they still hide mysterious ancient petroglyphs. In the Society Islands, you will be dazzled by the incomparable beauty of Huahine, by the turquoise waters of the Motu Mahana, our private vanilla- scented little paradise, by the sumptuous lagoon of Bora Bora, with its distinctly recognisable volcanic silhouette, and by Moorea, with its hillside pineapple plantations and its verdant peaks overlooking the island. Discover our excursions without further delay - click here! The information in this document is valid as of 28/9/2021 Marquesas, The Tuamotus & Society Islands YOUR STOPOVERS : PAPEETE, TAHITI ISLAND Embarkation 6/11/2021 from 4:00 pm to 5:00 pm Departure 6/11/2021 at 11:59 pm Capital of French Polynesia, the city Papeeteof is on the north-west coast of the island of Tahiti. -

Répartition De La Population En Polynésie Française En 2017

Répartition de la population en Polynésie française en 2017 PIRAE ARUE Paopao Teavaro Hatiheu PAPEETE Papetoai A r c h MAHINA i p e l d FAA'A HITIAA O TE RA e s NUKU HIVA M a UA HUKA r q PUNAAUIA u HIVA OA i TAIARAPU-EST UA POU s Taiohae Taipivai e PAEA TA HUATA s NUKU HIVA Haapiti Afareaitu FATU HIVA Atuona PAPARA TEVA I UTA MOO REA TAIARAPU-OUEST A r c h i p e l d Puamau TAHITI e s T MANIHI u a HIVA OA Hipu RA NGIROA m Iripau TA KAROA PUKA P UKA o NA PUKA Hakahau Faaaha t u Tapuamu d e l a S o c i é MAKEMO FANGATA U - p e l t é h i BORA BORA G c a Haamene r MAUPITI Ruutia A TA HA A ARUTUA m HUAHINE FAKARAVA b TATAKOTO i Niua Vaitoare RAIATEA e TAHITI r TAHAA ANAA RE AO Hakamaii MOORE A - HIK UE RU Fare Maeva MAIAO UA POU Faie HA O NUKUTAVAKE Fitii Apataki Tefarerii Maroe TUREIA Haapu Parea RIMATARA RURUTU A r c h Arutua HUAHINE i p e TUBUAI l d e s GAMBIE R Faanui Anau RA IVAVAE A u s Kaukura t r Nombre a l AR UTUA d'individus e s Taahuaia Moerai Mataura Nunue 20 000 Mataiva RA PA BOR A B OR A 10 000 Avera Tikehau 7 000 Rangiroa Hauti 3 500 Mahu Makatea 1 000 RURUT U TUBUAI RANGIROA ´ 0 110 Km So u r c e : Re c en se m en t d e la p o p u la ti o n 2 0 1 7 - IS P F -I N SE E Répartition de la population aux Îles Du Vent en 2017 TAHITI MAHINA Paopao Papetoai ARUE PAPEETE PIRAE HITIAA O TE RA FAAA Teavaro Tiarei Mahaena Haapiti PUNAAUIA Afareaitu Hitiaa Papenoo MOOREA 0 2 Km Faaone PAEA Papeari TAIARAPU-EST Mataiea Afaahiti Pueu Toahotu Nombre PAPARA d'individus TEVA I UTA Tautira 20 000 Vairao 15 000 13 000 Teahupoo 10 000 TAIARAPU-OUEST -

The Effects of the Cyclones of 1983 on the Atolls of the Tuamotu Archipelago (French Polynesia)

THE EFFECTS OF THE CYCLONES OF 1983 ON THE ATOLLS OF THE TUAMOTU ARCHIPELAGO (FRENCH POLYNESIA) J. F. DUPON ORSTOM (French Institute ofScientific Research for Development through cooperation), 213 Rue Lafayette - 75480 Paris Cedex 10, France Abstract. In the TUAMOTU Archipelago, tropical cyclones may contribute to the destruction as well as to some building up of the atolls. The initial occupation by the Polynesians has not increased the vulnerability of these islands as much as have various recent alterations caused by European influence and the low frequency of the cyclone hazard itself. An unusual series of five cyclones, probably related to the general thermic imbalance of the Pacific Ocean between the tropics struck the group in 1983 and demonstrated this vulnerability through the damage that they caused to the environment and to the plantations and settle ments. However, the natural rehabilitation has been faster than expected and the cyclones had a beneficial result in making obvious the need to reinforce prevention measures and the protection of human settle ments. An appraisal of how the lack of prevention measures worsened the damage is first attempted, then the rehabilitation and the various steps taken to forestall such damage are described. I. About Atolls and Cyclones: Some General Information Among the islands of the intertropical area of the Pacific Ocean, most of the low-lying lands are atolls. The greatest number of them are found in this part of the world. Most atolls are characterized by a circular string of narrow islets rising only 3 to 10 m above the average ocean level. -

Makatea: a Site of Major Importance for Endemic Birds English Pdf 1.92

MAKATEA, A SITE OF MAJOR IMPORTANCE FOR ENDEMIC BIRDS BIODI VERSITY CO NSERVATION LESSONS LEARNED TECHNICAL SERIES 16 BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION LESSONS LEARNED TECHNICAL SERIES 16 Makatea, a site of major importance for endemic birds Biodiversity Conservation Lessons Learned Technical Series is published by: Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) and Conservation International Pacific Islands Program (CI-Pacific) PO Box 2035, Apia, Samoa T: + 685 21593 E: [email protected] W: www.conservation.org The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. A fundamental goal is to ensure civil society is engaged in biodiversity conservation. Conservation International Pacific Islands Program. 2013. Biodiversity Conservation Lessons Learned Technical Series 16: Makatea, a site of major importance for endemic birds. Conservation International, Apia, Samoa Author: Thomas Ghestemme, Société d’Ornithologie de Polynésie Design/Production: Joanne Aitken, The Little Design Company, www.thelittledesigncompany.com Cover Photograph: Ducula aurorae © T Ghestemme/SOP Series Editor: Leilani Duffy, Conservation International Pacific Islands Program Conservation International is a private, non-profit organization exempt from federal income tax under section 501c(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. OUR MISSION Building upon a strong foundation of science, partnership and field -

TAHITI.2016 the Best of the TUOMOTU Archipelago MAY 15-25, 2016

TAHITI.2016 The Best of the TUOMOTU Archipelago MAY 15-25, 2016 If you have thought of warm crystalline South Pacific Ocean, little sand islets with coconut palms swaying down to the waterline and water to blue it appears electric? Very few of us are immune to this sirens call of French Polynesia’s image – real or imagined - and so these celebrated gems of the South Pacific have become a crossroads for dreamers, adventurers and escapist sharing a common wanderlust. We count ourselves among these folk… following in the wake of Magellan, Cook and Wallis, but by means easier than they could have ever imagined. As a diver, there is also something special beneath the azure surface that beckons, something never painted by Gauguin. In fact, the far-flung waters around French Polynesia are some of the SHARK-iest in the world… and the high voltage diving serves up the kind excitement not every paradise can deliver. The expedition is scheduled for MAY 15-25, a 10 day itinerary starting in the famed atoll of Rangiroa and weather permitting include Tikehau, Apataki, Toau and will end the journey in the stunning atoll of Fakarava. We may also get a chance to stop at a couple of others along the way. The diving is off tenders that transport us to the sites where strong currents can be present. The thrill is not only to witness what gets drawn to these spots but also to ride the crystalline currents without fighting them. Advanced diver and Nitrox certification required to join this trip. -

TUAMOTU Et GAMBIER S Ocié T É ARCHIPEL DES TUAMOTU Gambier Pg.60 COBIA III

DESSERTE ARCHIPELS DES É T OCIÉ TUAMOTU et GAMBIER S ARCHIPEL DES TUAMOTU Gambier Pg.60 COBIA III Pg.62 DORY Pg.64 MAREVA NUI TUAM-GAMB Pg.68 NUKU HAU Pg.72 SAINT XAVIER MARIS STELLA III Pg.76 ST X MARIS STELLA IV Pg.80 TAPORO VIII -44- tuamotu ouest Répartition du fret et des passagers des Tuamotu Ouest par île en 2017 Faka- Maka- Matai- Rangi- Taka- Aven- Total Fret Ahe Apataki Aratika Arutua rava Kauehi Kaukura tea Manihi va Niau roa Raraka Taiaro poto Takaroa Tikehau Toau ture T. Ouest Alimentaire 240 208 31 480 592 52 178 15 307 114 22 2 498 11 292 255 464 1 589 7 348 Mat.CONSTRUCTION 301 174 64 729 830 23 76 23 969 1 096 23 6 056 50 396 426 372 693 12 301 HYDROCARBURE 92 207 28 286 594 87 176 9 238 312 87 3 311 22 150 303 487 2 410 8 799 DIVERS 320 144 57 552 1 067 105 193 71 371 2 085 86 1 863 28 255 255 496 1 38 7 987 FRET ALLER 953 733 180 2 047 3 083 267 623 118 1 885 3 607 218 13 728 111 0 1 093 1 239 1 819 1 4 730 36 435 COPRAH 164 70 143 140 172 103 419 28 131 312 305 778 97 12 244 261 193 10 3 582 PRODUITS DE LA MER 9 12 6 54 7 9 34 3 19 6 3 45 13 9 15 4 248 PRODUITS AGRICOLES 1 2 1 1 1 1 2 9 PRODUCTIONS DES ÎLES 62 31 1 217 14 2 11 1 14 10 36 5 44 23 471 DIVERS 50 39 4 82 81 27 33 23 101 213 25 813 16 1 52 84 214 1 858 FRET RETOUR 286 152 156 493 274 141 497 55 266 531 344 1 673 126 13 311 404 436 12 6 168 Total FRET (en t) 1 239 885 336 2 540 3 357 408 1 120 173 2 151 4 138 562 15 401 237 13 1 404 1 643 2 255 13 4 730 42 603 Passagers et Ahe Apataki Aratika Arutua Faka- Kauehi Kaukura Maka- Manihi Matai- Niau Rangi- Raraka Taiaro Taka- Takaroa Tikehau Toau Aven- Total Véhicules rava tea va roa poto ture T. -

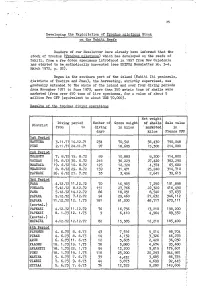

Developing the Exploitation of <I>Trochus Niloticus</I> Stock on the Tahiti Reefs

35 Developing the Exploitation of Trochu3 niloticus Stock onithe_Ta'hiti Reefs Readers of our Newsletter have already been informed that the stock of trochus (Trochug niloticus) which has developed on the reefs of Tahiti, from a few dozen specimens introduced in 1957 from Hew Caledonia has started to be methodically harvested (see SPIPDA Newsletter ITo. 3-4, March 1972, p. 32). Begun in the southern part of the island (Tahiti Iti peninsula, districts of Tautira and Pueu), the harvesting, strictly supervised, was gradually extended to the whole of the island and over four diving periods fjrom November 1971 to June 1973? more than 350 metric tons of shells were marketed (from over 450 tons of live specimens, for a value of about 5 million Frs CTP (equivalent to about US$ 70,000). Results of .the trochus. diving operations Net weight Diving period Number of Gross weight of shells Sale value District from to diving in kilos ' marketed in days kilos Francs CPP 1st Period TAUTIRA 3-11.71 I4.l2.7i 234 70,541 56,430 790,048 .. PUEU 2.11 .71 24.11.71 97 18,605 ... 15,300 214,000 2nd Period TOAHOTU 7. 8.72 15. 8,72 89 10r883 8,200 114,800 : VAIRAO 15. 8.72 30. 8.72 216 36J229 27,420 362,290 , MAATAIA. 19. 6.72 10. 8o72 125 12,724 4,374 65,600 TEAHUPOO 8. 8.72 29. 8.72 159 31,471 25,240' 314,710 PAPEARI 26. 6.72 27. 7.72 35 3,456 2,641 39,615 ; 3rd Period FAAA 4.12,72 11.12.72 70 16,983 7,250 101,898 PIMAAUA 5.12.72 8,12.72 151 27,766 .22,320 416,490 PAEA 5.12.72 14*12.72 86 18,051 8, 540 97,633 PAPARA 5.12.72 7.12.72 94 29,460 21,632 346,112 PAPARA 11.12.72 12. -

REP+ Des Tuamotu Et Gambier Who’S Who De L’Éducation Prioritaire

REP+ des Tuamotu et Gambier Who’s who de l’éducation prioritaire Vice-recteur de l’académie de Polynésie-Française M. Philippe COUTURAUD Directeur général de l’éducation et de l’enseignement supérieur M. Thierry DELMAS Chargée de mission de l’éducation prioritaire M. Erik DUPONT LES PILOTES Inspecteur de l’Education nationale (IEN) : Mme Dominique BATLLE Téléphone : 40.46.29.52 E-mail : [email protected] Inspecteur pédagogique régional référent (IA-IPR) : M. Didier RIGGOTARD E-mail : [email protected] Principaux de collège : Antenne de Hao Antenne de Makemo Antenne de Rangiroa M. Patrice LEROY M. Jean-Pierre MESNARD M. Hervé BIGOTTE Téléphone : 40.97.02.99 Téléphone : 40.98.03.69 Téléphone : 40.93.13.40 E-mail : E-mail : E-mail : [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Conseillers pédagogiques d’éducation prioritaire Mme Herenui PRATX M. Andy CHANSAUD Téléphone : 40.46.29.55 Téléphone : 40.46.29.55 E-mail : [email protected] E-mail : [email protected] Coordonnateur de réseau d’éducation prioritaire Téléphone : 40.46.29.52 E-mail : LES ECOLES : ANTENNE DE HAO ATOLL ECOLE TELEPHONE COURRIEL Hao Ecole primaire TE TAHUA O FARIKI 40 97 03 85 [email protected] Nukutavake Ecole primaire NUKUTAVAKE 40 98 72 91 [email protected] Puka Puka Ecole primaire TE ONE MAHINA 40 97 42 35 [email protected] Rikitea Ecole primaire MAPUTEOA 40 97 82 93 [email protected] Tepoto Ecole primaire TEPOTO 40 97 32 50 [email protected] Napuka Ecole -

Underground Pacific Island Handbook

Next: Contents Underground Pacific Island Handbook unknown ● Contents ● List of Tables ● List of Figures ● ROUTES AND PASSAGE TIMES ● WINDS, WAVES, AND WEATHER ❍ CURRENTS ● NAVIGATION IN CORAL WATERS ❍ Approaches ❍ Running The Passes ❍ Estimating Slack Water ❍ Navigating by Eye ❍ MARKERS AND BUOYS ■ Uniform Lateral System ■ Special Topmarks for Prench Polynesia ■ Ranges and Entrance Beacons ■ United States System ❍ REFERENCES AND CHART LISTS ■ Books ■ Charts and Official Publications ■ Pilots and Sailing Directions ● FORMALITIES ❍ Basic Entry Procedures ❍ Leaving ❍ Special Requirements for Different Areas ■ French Polynesia ■ The Cook Islands ■ The Hawaiian Islands ■ Pitcairn Island ■ Easter Island ● FISH POISONING (CIGUATERA) ❍ Symptoms ❍ Treatment ❍ Prevention ❍ Other Fish Poisoning ● ILES MARQUISES ❍ Weather ❍ Currents ❍ Clearance and Travel Notes ❍ NUKU HIVA ■ Baie de Anaho ■ Baie Taioa ■ Baie de Taiohae ■ Baie de Controleut ❍ UA HUKA ■ Baie de Vaipaee ■ Baie-D'Hane ■ Baie Hanvei ❍ UA POU ■ Baie d'Hakahau ■ Baie d'Hakahetau ■ Baie Aneo ■ Baie Vaiehu ■ Baie Hakamaii ❍ HIVA OA ■ Baies Atuona and Taahuku ■ Baie Hanamenu ❍ TADUATA ■ Baie Vaitahu ❍ FATU-HIVA ■ Baie des Vietpes (Haha Vave) ■ Baie d'Omoa ❍ MOTANE ■ Northern Islets ● ARCHIPEL DES TUAMOTU ❍ Restricted Areas ❍ Routes Through the Archipelago ❍ ATOLL MANIHI ❍ ATOLL AHE ■ Passe Reianui ■ ILES DU ROI GEORGES ❍ TAKAROA ❍ TAKAPOTO ❍ TIKEI ❍ MATAIVA ❍ TIKEHAU ❍ ILE MAKATEA ❍ RANGIROA ■ GROUPE DES ILES PALLISER ❍ ARUTUA ❍ KAUKURA ❍ APATAKI ❍ ARATIKA ❍ TOAU ❍ FAKARAVA ❍ FAAITE ❍ KAUEIII -

Use of the European Severe Weather Database to Verify Satellite-Based Storm Detection Or Nowcasting

USE OF THE EUROPEAN SEVERE WEATHER DATABASE TO VERIFY SATELLITE-BASED STORM DETECTION OR NOWCASTING Nikolai Dotzek1,2, Caroline Forster1 1 Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt (DLR), Institut für Physik der Atmosphäre, Oberpfaffenhofen, 82234 Wessling, Germany 2 European Severe Storms Laboratory, Münchner Str. 20, 82234 Wessling, Germany Abstract Severe thunderstorms constitute a major weather hazard in Europe, with an estimated total damage of € 5-8 billion each year. Yet a pan-European database of severe weather reports in a homogeneous data format has become available only recently: the European Severe Weather Database (ESWD). We demonstrate the large potential of ESWD applications for storm detection and forecast or now- casting/warning verification purposes. The study of five warm-season severe weather days in Europe from 2007 and 2008 revealed that up to 47% of the ESWD reports were located exactly within the polygons detected by the Cb-TRAM algorithm for three different stages of deep moist convection. The cool-season case study of extratropical cyclone “Emma” on 1 March 2008 showed that low-topped winter thunderstorms can provide a challenge for satellite storm detection and nowcasting adapted to warm-season storms with high, cold cloud tops. However, this case also demonstrated how ESWD reports alone can still be valuable to identify the hazardous regions along the cold front of the cyclone. 1. INTRODUCTION Severe thunderstorms, with their attendant strong winds, hail, flooding, and tornadoes, are common phenomena in many European countries, leading to a total damage estimate of 5 to 8 billion euros per year (source: Munich Re Group). Extreme events like an F4 tornado in France and an F3 downburst in Austria in 2008 exemplify these damage totals.