' and Muktibodh's “Void” and “So Very Far”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

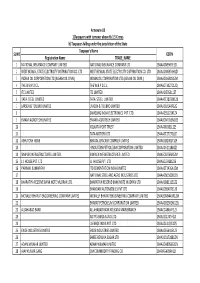

Directory of Members

Centre Employee Id Staff Employee Name Designation Department Employment Type Level Basic/Consolidated Pay Bangalore 100149 MAS(B) Ms Jyotsna Muralidhar Kumble Manager (Admin) Admin Regular Level - 12 122900 Bangalore 100190 MAS(B) Mr R Guru Prasad Manager (Admin) Admin Regular Level - 12 99800 Bangalore 100191 MAS(B) Ms M Savithri Manager (Admin) Admin Regular Level - 12 99800 Bangalore 100376 MTS(B) Mr Jayan M P Senior Technical Officer UCHR Regular Level - 11 99500 Bangalore 100391 MTS(B) Mr Rajesh Kumar M Senior Technical Officer OGGI Regular Level - 11 88400 Bangalore 100410 MAS(B) Mr Aswath Rao S Senior Purchase Officer BD Regular Level - 11 91100 Bangalore 100520 MTS(A) Mr B S Bindhumadhava Senior Director RTSSG Regular Level - 14 218200 Bangalore 100533 MAS(B) Ms Veena K S Senior Admin Officer ED's Office Regular Level - 11 85800 Bangalore 100534 MAS(B) Ms Binu George Senior Admin Officer HRD Regular Level - 11 83300 Bangalore 100535 MAS(B) Ms Vidya K Murthy Admin Executive Admin Regular Level - 7 68000 Bangalore 100538 MAS(B) Ms D Gladis Flora Senior Personal Private Secretary ED's Office Regular Level - 12 88700 Bangalore 100539 MTS(A) Mr B Jayanth Senior Technical Officer RTSSG Regular Level - 11 85800 Bangalore 100543 MAS(B) Ms Jalajakshi H V Librarian Finance Regular Level - 9 80200 Bangalore 100545 MAS(B) Mr S. Muthukumaran Manager (Admin) Admin Regular Level - 12 88700 Bangalore 100548 MTS(A) Mr B A Sreekantha Joint Director SSEN Regular Level - 13 151400 Bangalore 100638 MAS(B) Ms Vanajakshi Raghu Personal Secretary Admin -

Govt Unlikely to Trim GST on Automobiles

FRIDAY • AUGUST 27, 2021 MUMBAI ₹10 • Pages 10 • Volume 28 • Number 238 AUTO FOCUS DATA FOCUS RAISING THE RED FLAG On the 50th anniversary of the Covidrelated health claims in just the The independent auditors of Tata Sons original Countach, Lamborghini’s first five months of FY22 have already have expressed concerns over AirAsia futuristic hybrid makes its debut p7 topped claims of whole of FY21 p2 India’s ability to sustain as a going concern p2 Bengaluru Chennai Coimbatore Hubballi Hyderabad Kochi Kolkata Madurai Malappuram Mangaluru Mumbai Noida Thiruvananthapuram Tiruchirapalli Tirupati Vijayawada Visakhapatnam Regd. TN/ARD/14/09-11, RNI No. 55320/94 Boeing MAX 737 HIGHER FAMILY PENSION, NPS Govt unlikely to trim to fly again in India PSBs to make ₹21,300crore OUR BUREAU New Delhi, August 26 The DirectorateGeneral of GST on automobiles Civil Aviation (DGCA) on additional provision yearly Top official says sop Thursday allowed Boeing MAX8 aircraft to fly again in To soften impact, not needed as sales the country. On account of two have picked up, no fatal accidents, the regulator will seek special RBI had halted operation of this dispensation to inventory buildup type of planes with effect from March 2019. spread it over 5 years OUR BUREAU As on date, SpiceJet is the New Delhi, August 26 only Indian carrier using Boe SHISHIR SINHA The government is unlikely to ing 737 MAXaircraft; it has 13 in New Delhi, August 26 ation of the 11 th bipartite set 2018, it was decided that for a oblige any time soon the auto Tax burden a singleclass configuration Public sector banks will have tlement on wage revision of Central government em mobile industry’s demand for each with capacity to carry 189 to set aside an additional public sector bank employ ployee, the mandatory con ■ lowering the Goods & Services All automobiles attract GST between 18% and 28% passengers. -

Unpaid Dividend-16-17-I2 (PDF)

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-2 CIN/BCIN L72200KA1999PLC025564 Prefill Company/Bank Name MINDTREE LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 17-JUL-2018 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 737532.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Proposed Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred (DD-MON-YYYY) 49/2 4TH CROSS 5TH BLOCK MIND00000000AZ00 Amount for unclaimed and A ANAND NA KORAMANGALA BANGALORE INDIA Karnataka 560095 72.00 24-Feb-2024 2539 unpaid dividend KARNATAKA 69 I FLOOR SANJEEVAPPA LAYOUT MIND00000000AZ00 Amount for unclaimed and A ANTONY FELIX NA MEG COLONY JAIBHARATH NAGAR INDIA Karnataka 560033 72.00 24-Feb-2024 2646 unpaid dividend BANGALORE PLOT NO 10 AIYSSA GARDEN IN301637-41195970- Amount for unclaimed and A BALAN NA LAKSHMINAGAR MAELAMAIYUR INDIA Tamil Nadu 603002 400.00 24-Feb-2024 0000 unpaid dividend -

Leave Granted. 2. These Appeals Arise out of the Judgment Dated 15.05

Bar & Bench (www.barandbench.com) REPORTABLE IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CRIMINAL APPELLATE JURISDICTION CRIMINAL APPEAL NO. 875 OF 2019 (Arising out of SLP(Crl.) No.9053 of 2016) BIRLA CORPORATION LIMITED ...Appellant VERSUS ADVENTZ INVESTMENTS AND HOLDINGS ...Respondents LIMITED & OTHERS WITH CRIMINAL APPEAL NO. 877 OF 2019 (Arising out of SLP(Crl.) No.4609 of 2019 @ D. No.6405 of 2019) BIRLA BUILDINGS LIMITED ...Appellant VERSUS BIRLA CORPORATION LIMITED ...Respondent WITH CRIMINAL APPEAL NO. 876 OF 2019 (Arising out of SLP(Crl.) No. 4608 of 2019 @ D. No.6122 of 2019) GOVIND PROMOTERS PVT. LTD. ...Appellant VERSUS BIRLA CORPORATION LIMITED ...Respondent J U D G M E N T R. BANUMATHI, J. Leave granted. 2. These appeals arise out of the judgment dated 15.05.2015 passed by the High Court of Calcutta in C.R.R. No.323 of 2011 in 1 Bar & Bench (www.barandbench.com) and by which the High Court quashed the complaint of the appellant-Company filed under Sections 379, 403 and 411 IPC read with Section 120-B IPC qua documents No.1 to 28 of the Schedule. Insofar as documents No.29 to 54 of the Schedule, the High Court remitted the matter to the trial court to proceed with the matter in accordance with law. 3. Being aggrieved by quashing of the complaint qua documents No.1 to 28, the appellant-complainant has preferred appeal (SLP (Crl.) No.9053 of 2016). Being aggrieved by remitting the matter to the trial court qua documents No.29 to 54, the respondents have filed appeal [SLP(Crl.) D No.6405 of 2019 and SLP(Crl.) D. -

The Wrestler's Body: Identity and Ideology in North India

The Wrestler’s Body Identity and Ideology in North India Joseph S. Alter UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford © 1992 The Regents of the University of California For my parents Robert Copley Alter Mary Ellen Stewart Alter Preferred Citation: Alter, Joseph S. The Wrestler's Body: Identity and Ideology in North India. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1992 1992. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft6n39p104/ 2 Contents • Note on Translation • Preface • 1. Search and Research • 2. The Akhara: Where Earth Is Turned Into Gold • 3. Gurus and Chelas: The Alchemy of Discipleship • 4. The Patron and the Wrestler • 5. The Discipline of the Wrestler’s Body • 6. Nag Panchami: Snakes, Sex, and Semen • 7. Wrestling Tournaments and the Body’s Recreation • 8. Hanuman: Shakti, Bhakti, and Brahmacharya • 9. The Sannyasi and the Wrestler • 10. Utopian Somatics and Nationalist Discourse • 11. The Individual Re-Formed • Plates • The Nature of Wrestling Nationalism • Glossary 3 Note on Translation I have made every effort to ensure that the translation of material from Hindi to English is as accurate as possible. All translations are my own. In citing classical Sanskrit texts I have referenced the chapter and verse of the original source and have also cited the secondary source of the translated material. All other citations are quoted verbatim even when the English usage is idiosyncratic and not consistent with the prose style or spelling conventions employed in the main text. A translation of single words or short phrases appears in the first instance of use and sometimes again if the same word or phrase is used subsequently much later in the text. -

History of Science Museums and Planetariums in India*

Indian Journal of History of Science, 52.3 (2017) 357-368 DOI: 10.16943/ijhs/2017/v52i3/49167 Project Report History of Science Museums and Planetariums in India* Jayanta Sthanapati** 1. INTRODUCTION III. Planetariums The current study has been envisaged to IV. Natural History Museums present a comprehensive history of the V. Mobile Science Exhibition development of Indian Science Museums and Planetariums, and study their exhibits and VI. Interview of Pioneers of Science Museums and activities. Based on available documents, their Planetariums impact in enhancing public understanding of Details of the findings are presented in the science and technology has also been attempted. following sections: Two major accounts on science museum (or science centre) movement in India, written by 2. SCIENCE MUSEUMS, SCIENCE CENTRES Dr Saroj Ghose, former Director General of AND SCIENCE CITIES NCSM (1986-1997) and Shri Ingit K Mukhopadhyay, former DG NCSM (1997-2009) In the early years of 1950s, Pandit and on Indian planetariums by Shri Piyush Pandey, Jawaharlal Nehru, First Prime Minister of India, former Director of Nehru Planetarium, Mumbai Shri G D Birla, a renowned industrialist, Prof K S (2003-2011) though not very comprehensive in Krishnan, a world renowned physicist and Dr B historical studies of science museums and C Roy, a renowned physician and the then Chief planetariums in India has helped us a lot to prepare Minister of West Bengal took considerable interest our document. However, there was not a single in establishment of Science Museums in the account available on the history of natural history country. With their support and under the museums in India. -

Hospital List for Medicare Under Health Insurance| Royal Sundaram

SL.N STD O. HOSPITAL NAME ADDRESS - 1 ADDRESS - 2 CITY PIN CODE STATE ZONE CODE TEL 1 TEL - 2 FAX - 1 SALUTATION FIRST NAME MIDDLE SURNAME E MAIL ID (NEAR PEERA 1 SHRI JIYALAL HOSPITAL & MATERNITY CENTRE 6, INDER ENCLAVE, ROHTAK ROAD GARHI CHOWK) DELHI 110 087 DELHI NORTH 011 2525 2420 2525 8885 MISS MAHIMA 2 SUNDERLAL JAIN HOSPITAL ASHOK VIHAR, PHASE II DELHI 110 052 DELHI NORTH 011 4703 0900 4703 0910 MR DINESH K KHANDELWAL 3 TIRUPATI STONE CENTRE & HOSPITAL 6,GAGAN VIHAR,NEW DELHI DELHI 110051 DELHI NORTH 011 22461691 22047065 MS MEENU # 2, R.B.L.ISHER DAS SAWHNEY MARG, RAJPUR 4 TIRATH RAM SHAH HOSPITAL ROAD, DELHI 110054 DELHI NORTH 011 23972425 23953952 MR SURESH KUMAR 5 INDRAPRASTHA APOLLO HOSPITALS SARITA VIHAR DELHI MATHURA ROAD DELHI 110044 DELHI NORTH 011 26925804 26825700 MS KIRAN 6 SATYAM HOSPITAL A4/64-65, SECTOR-16, ROHINI, DELHI 110 085 DELHI NORTH 011 27850990 27295587 DR VIJAY KOHLI CS / OCF - 6 (NEAR POPULAR APARTMENT AND SECTOR - 13, 7 BHAGWATI HOSPITAL MOTHER DIARY BOOTH) ROHINI DELHI 110 085 DELHI NORTH 011 27554179 27554179 DR NARESH PAMNANI NETRAYATAN DR. GROVER'S CENTER FOR EYE 8 CARE S 371, GREATER KAILASH 2 DELHI 110 048 DELHI NORTH 011 29212828 29212828 DR VISHAL GROVER 9 SHROFF EYE CENTRE A-9, KAILASH COLONY DELHI 110048 DELHI NORTH 011 29231296 29231296 DR KOCHAR MADHUBAN 10 SAROJ HOSPITAL & HEART INSTITUTE SEC-14, EXTN-2, INSTITUTIONAL AREA CHOWK DELHI 110 085 DELHI NORTH 011 27557201 2756 6683 MR AJAY SHARMA 11 ADITYA VARMA MEDICAL CENTRE 32, CHITRA VIHAR DELHI 110 092 DELHI NORTH 011 2244 8008 22043839 22440108 MR SANOJ GUPTA SWARN CINEMA 12 SHRI RAMSINGH HOSPTIAL AND HEART INSTITUTE B-26-26A, EAST KRISHNA NAGAR ROAD DELHI 110 051 DELHI NORTH 011 209 6964 246 7228 MS ARCHANA GUPTA BALAJI MEDICAL & DIAGNOSTIC RESEARCH 13 CENTRE 108-A, I.P. -

Orient Paper & Industries Limited

DRAFT LETTER OF OFFER (Private and Confidential) For Equity Shareholders of the Company only Dated January 10, 2007 ORIENT PAPER & INDUSTRIES LIMITED (Originally incorporated under the Indian Companies Act, 1913, as “Orient Paper Mills Limited” vide certificate of registration dated July 25, 1936 issued by Registrar of Joint Stock Companies, Bengal and received its certificate of commencement of business on July 30, 1936. The name of our Company was changed to “Orient Paper & Industries Limited” on September 13, 1978. The registered office of our Company was shifted from 8, Royal Exchange Place, Calcutta-700001, West Bengal to Brajrajnagar, District – Jharsuguda - 768216, Orissa, in the year 1947 and further shifted to its current address, Unit- VIII, Plot No.7, Bhoinagar, Bhubaneswar-751012, Orissa in the year 2000. Registered Office: Unit-VIII, Plot No. 7, Bhoinagar, Bhubaneswar-751 012, Orissa Head office: 9/1, R. N. Mukherjee Road, Kolkata - 700 001 Contact Person & Compliance Officer: Mr. P.K. Sonthalia, President (Finance) & CFO, Tel: +91 33 2248 3406; Fax: +9133 2242 0933; E-mail: [email protected] DRAFT LETTER OF OFFER Issue of [y] Equity Shares of Rs. 10 each for cash at a price of Rs. [y] (including a premium of Rs. [y]) per Equity Share not exceeding an aggregate amount of Rs. 17,500 lacs on rights basis to the existing Equity Shareholders of our Company in the ratio of [y] Equity Share for every [y] Equity Shares held on Record Date i.e. [y] The face value of the Equity Shares is Rs. 10 per share and the Issue Price is [y] times the face value. -

Dictated Portion to Mr

REPORTABLE IN THE SUPRME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL APPELALTE JURISIDCTION CIVIL APPEAL NO. _2277 OF 2008 (Arising out of SLP (C) NO. 2089 OF 2007) Krishna Kumar Birla .... Appellant Versus Rajendra Singh Lodha and others … Respondents WITH CIVIL APPEAL NOS. 2275,2279,2276,2274,2278 OF 2007 (Arising out of SLP (C) NOS. 10176, 10571, 19040, 2090 AND 2091 OF 2007) S.B. SINHA, J. 1. Leave granted. INTRODUCTION 2 2. What is a caveatable interest within the meaning of the Indian Succession Act, 1925 (1925 Act) vis-a-vis the Rules framed by the Calcutta High Court in the year 1940 is the question involved herein. BACKGROUND FACTS 3. Smt. Priyamvada Devi Birla (PDB) and her husband Madhav Prasad Birla (MPB) were admittedly very wealthy persons. They owned an industrial empire known as the MP Birla Group of Industries. They were issueless and known for their charitable disposition. They used to run several charitable institutions. 4. Both MPB and PDB are said to have executed mutual wills on identical terms on or about 10th May, 1981 bequeathing his/her respective estate(s) barring certain specific legacies to the other and on the death of the survivor to the ‘charities’ to be nominated by the executors. However, the said wills were revoked and another set of mutual wills were executed on 13th July, 1982 in terms whereof, four executors were appointed in each set of Will (1982 Will). The executors nominated in MPB’s Will were :- 3 1. Smt. Priyamvada Devi Birla (PDB) 2. Krishna Kumar Birla (KKB) 3. Kashinath Tapuria and 4. -

Annexure 1B 18416

Annexure 1 B List of taxpayers allotted to State having turnover of more than or equal to 1.5 Crore Sl.No Taxpayers Name GSTIN 1 BROTHERS OF ST.GABRIEL EDUCATION SOCIETY 36AAAAB0175C1ZE 2 BALAJI BEEDI PRODUCERS PRODUCTIVE INDUSTRIAL COOPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED 36AAAAB7475M1ZC 3 CENTRAL POWER RESEARCH INSTITUTE 36AAAAC0268P1ZK 4 CO OPERATIVE ELECTRIC SUPPLY SOCIETY LTD 36AAAAC0346G1Z8 5 CENTRE FOR MATERIALS FOR ELECTRONIC TECHNOLOGY 36AAAAC0801E1ZK 6 CYBER SPAZIO OWNERS WELFARE ASSOCIATION 36AAAAC5706G1Z2 7 DHANALAXMI DHANYA VITHANA RAITHU PARASPARA SAHAKARA PARIMITHA SANGHAM 36AAAAD2220N1ZZ 8 DSRB ASSOCIATES 36AAAAD7272Q1Z7 9 D S R EDUCATIONAL SOCIETY 36AAAAD7497D1ZN 10 DIRECTOR SAINIK WELFARE 36AAAAD9115E1Z2 11 GIRIJAN PRIMARY COOPE MARKETING SOCIETY LIMITED ADILABAD 36AAAAG4299E1ZO 12 GIRIJAN PRIMARY CO OP MARKETING SOCIETY LTD UTNOOR 36AAAAG4426D1Z5 13 GIRIJANA PRIMARY CO-OPERATIVE MARKETING SOCIETY LIMITED VENKATAPURAM 36AAAAG5461E1ZY 14 GANGA HITECH CITY 2 SOCIETY 36AAAAG6290R1Z2 15 GSK - VISHWA (JV) 36AAAAG8669E1ZI 16 HASSAN CO OPERATIVE MILK PRODUCERS SOCIETIES UNION LTD 36AAAAH0229B1ZF 17 HCC SEW MEIL JOINT VENTURE 36AAAAH3286Q1Z5 18 INDIAN FARMERS FERTILISER COOPERATIVE LIMITED 36AAAAI0050M1ZW 19 INDU FORTUNE FIELDS GARDENIA APARTMENT OWNERS ASSOCIATION 36AAAAI4338L1ZJ 20 INDUR INTIDEEPAM MUTUAL AIDED CO-OP THRIFT/CREDIT SOC FEDERATION LIMITED 36AAAAI5080P1ZA 21 INSURANCE INFORMATION BUREAU OF INDIA 36AAAAI6771M1Z8 22 INSTITUTE OF DEFENCE SCIENTISTS AND TECHNOLOGISTS 36AAAAI7233A1Z6 23 KARNATAKA CO-OPERATIVE MILK PRODUCER\S FEDERATION -

FINAL DISTRIBUTION.Xlsx

Annexure-1B 1)Taxpayers with turnover above Rs 1.5 Crores b) Taxpayers falling under the jurisdiction of the State Taxpayer's Name SL NO GSTIN Registration Name TRADE_NAME 1 NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LIMITED NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LTD 19AAACN9967E1Z0 2 WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD 19AAACW6953H1ZX 3 INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) 19AAACI1681G1ZM 4 THE W.B.P.D.C.L. THE W.B.P.D.C.L. 19AABCT3027C1ZQ 5 ITC LIMITED ITC LIMITED 19AAACI5950L1Z7 6 TATA STEEL LIMITED TATA STEEL LIMITED 19AAACT2803M1Z8 7 LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED 19AAACL0140P1ZG 8 SAMSUNG INDIA ELECTRONICS PVT. LTD. 19AAACS5123K1ZA 9 EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED 19AABCN7953M1ZS 10 KOLKATA PORT TRUST 19AAAJK0361L1Z3 11 TATA MOTORS LTD 19AAACT2727Q1ZT 12 ASHUTOSH BOSE BENGAL CRACKER COMPLEX LIMITED 19AAGCB2001F1Z9 13 HINDUSTAN PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED. 19AAACH1118B1Z9 14 SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. 19AAECS0765R1ZM 15 J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD 19AABCJ5928J2Z6 16 PARIMAL KUMAR RAY ITD CEMENTATION INDIA LIMITED 19AAACT1426A1ZW 17 NATIONAL STEEL AND AGRO INDUSTRIES LTD 19AAACN1500B1Z9 18 BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. 19AAACB8111E1Z2 19 BHANDARI AUTOMOBILES PVT LTD 19AABCB5407E1Z0 20 MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED 19AABCM9443R1ZM 21 BHARAT PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED 19AAACB2902M1ZQ 22 ALLAHABAD BANK ALLAHABAD BANK KOLKATA MAIN BRANCH 19AACCA8464F1ZJ 23 ADITYA BIRLA NUVO LTD. 19AAACI1747H1ZL 24 LAFARGE INDIA PVT. LTD. 19AAACL4159L1Z5 25 EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED 19AAACE6641E1ZS 26 SHREE RENUKA SUGAR LTD. 19AADCS1728B1ZN 27 ADANI WILMAR LIMITED ADANI WILMAR LIMITED 19AABCA8056G1ZM 28 AJAY KUMAR GARG OM COMMODITY TRADING CO. -

Alphabetical List of Recommendations Received for Padma Awards - 2014

Alphabetical List of recommendations received for Padma Awards - 2014 Sl. No. Name Recommending Authority 1. Shri Manoj Tibrewal Aakash Shri Sriprakash Jaiswal, Minister of Coal, Govt. of India. 2. Dr. (Smt.) Durga Pathak Aarti 1.Dr. Raman Singh, Chief Minister, Govt. of Chhattisgarh. 2.Shri Madhusudan Yadav, MP, Lok Sabha. 3.Shri Motilal Vora, MP, Rajya Sabha. 4.Shri Nand Kumar Saay, MP, Rajya Sabha. 5.Shri Nirmal Kumar Richhariya, Raipur, Chhattisgarh. 6.Shri N.K. Richarya, Chhattisgarh. 3. Dr. Naheed Abidi Dr. Karan Singh, MP, Rajya Sabha & Padma Vibhushan awardee. 4. Dr. Thomas Abraham Shri Inder Singh, Chairman, Global Organization of People Indian Origin, USA. 5. Dr. Yash Pal Abrol Prof. M.S. Swaminathan, Padma Vibhushan awardee. 6. Shri S.K. Acharigi Self 7. Dr. Subrat Kumar Acharya Padma Award Committee. 8. Shri Achintya Kumar Acharya Self 9. Dr. Hariram Acharya Government of Rajasthan. 10. Guru Shashadhar Acharya Ministry of Culture, Govt. of India. 11. Shri Somnath Adhikary Self 12. Dr. Sunkara Venkata Adinarayana Rao Shri Ganta Srinivasa Rao, Minister for Infrastructure & Investments, Ports, Airporst & Natural Gas, Govt. of Andhra Pradesh. 13. Prof. S.H. Advani Dr. S.K. Rana, Consultant Cardiologist & Physician, Kolkata. 14. Shri Vikas Agarwal Self 15. Prof. Amar Agarwal Shri M. Anandan, MP, Lok Sabha. 16. Shri Apoorv Agarwal 1.Shri Praveen Singh Aron, MP, Lok Sabha. 2.Dr. Arun Kumar Saxena, MLA, Uttar Pradesh. 17. Shri Uttam Prakash Agarwal Dr. Deepak K. Tempe, Dean, Maulana Azad Medical College. 18. Dr. Shekhar Agarwal 1.Dr. Ashok Kumar Walia, Minister of Health & Family Welfare, Higher Education & TTE, Skill Mission/Labour, Irrigation & Floods Control, Govt.