Journal of the Southampton Local History Forum No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10 Appendix 1 ENVIRONMENT & TRANSPORT PORTFOLIO

sep2009 ITEM NO: 10 Appendix 1 ENVIRONMENT & TRANSPORT PORTFOLIO Prior to Actual Estimate Estimate Estimate Estimate Scheme 2008/09 2008/09 2009/10 2010/11 2011/12 Later Yrs Total No. Description £000 £000 £000 £000 £000 £000 £000 Project Manager Approved Schemes Accessibility C7171 Accessibility 105 37 126 285 0 0 553 Smith, Colin 105 37 126 285 0 0 Active Travel C7121 Walking 1,652 541 753 120 0 0 3,066 Marshall, Anthony C7131 Cycling 2,487 150 318 0 0 0 2,955 Bostock, Dale 4,139 691 1,071 120 0 0 Bridges C6120 Chantry Road Footbridge 89 80 0 73 0 0 242 Simpkins, John C7911 Bridges 4,760 427 3,042 886 200 0 9,315 Simpkins, John 4,849 507 3,042 959 200 0 City & District Centres C6110 Canute Road (C6110) 368 1 0 0 0 0 369 Westgate, Anthony C6160 Portswood Broadway - Phase 2 615 4 0 0 0 0 619 Westgate, Anthony C7360 Local and District Centres Improvements 134 62 51 240 0 0 487 Marshall, Anthony C8900 City Centre Paving 947 66 0 0 0 0 1,013 Taylor, Simon 2,064 133 51 240 0 0 Environment & Sustainability C2050 Carbon Emissions Inventory 0 13 19 19 0 0 51 Clark, Robert C2350 Coastal Protect'N Feasib.Study 74 21 10 0 0 0 105 Crighton, Robert C2400 E-Planning (PDG) 86 189 185 100 0 0 560 Nichols, Paul C2410 Mobile Working 0 0 50 0 0 0 50 Nichols, Paul C2520 Salix Energy Efficiency Measures 47 85 151 142 0 0 425 Clark, Robert 207 308 415 261 0 0 General Environment C2040 Weston Shore Improvements 1,256 41 2 0 0 0 1,299 Moore, Malcolm C2600 Mansel and Green Park Improvements 408 15 0 0 0 0 423 Friedman, Danielle C2650 Refurbishment of the Crematorium -

12-GF Capital Outturn-Appendix 2

ITEM NO:12 APPENDIX 2 CHILDREN'S SERVICES & LEARNING Scheme Description Budget Actual Variance Total Total No 2009/10 2 0 09/10 2 0 0 9/10 S c heme Actual to £000's £000's £000's Budget 3 1 /03/10 £000's £000's Academies E9054 Acadamies Management 250 441 191 806 547 E9056 Mayfield Academy Site Access 600 570 (30) 830 639 E9057 Academies - Capital Works 178 5 (173) 1,025 5 1,028 1,016 (12) 2,661 1,191 Bitterne Park 6Th Form E9058 Bitterne Park 6Th Form 638 606 (32) 6,380 606 Children's Centres Phase 3 1,049 634 (415) 4,624 641 Children's Centres Capital Projects E4049 Childrens Centres - Retentions 39 26 (13) 79 26 E7079 Woolston Infant Children's Centre 0 6 6 250 256 E8050 Children's Centres - Phase 1 90 48 (42) 2,127 2,085 E8052 Harefield Primary Children's Centre 111 (8) (119) 800 675 E9071 Thornhill Primary Children's Centre 33 (27) (60) 999 939 E9072 Townhill Junior Children's Centre 56 (25) (81) 974 893 329 20 (309) 5,229 4,874 CS&L General Other E8180 Sports Development 300 17 (283) 300 17 E9031 Schools Devolved Capital 2008-11 3,314 3,388 74 9,635 6,652 E9110 Mods - Shirley Warren Sch Library Buildi 16 5 (11) 16 5 3,630 3,410 (220) 9,951 6,674 14-19 Diplomas, SEN & Disabilities E6922 14-19 Diplomas, Sen And Disabilities 0 75 75 6,075 75 ICT E8160 Ict Harnessing Technology Grant 584 638 54 1,713 643 E8165 Home Access To Targeted Groups 154 154 0 154 154 R9911 Integrated Childrens System 35 9 (26) 200 174 773 801 28 2,067 971 School Kitchens E9023 Foundry Lane Primary School Kitchen 78 31 (47) 425 53 E9112 Mods - Springhill Primary -

Carnival Corporation Carnival Plc

UNITED STATES OMB APPROVAL SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION OMB Number: 3235-00595 Washington, D.C. 20549 Expires: February 28, 2006 SCHEDULE 14A Estimated average burden hours per response......... 12.75 Proxy Statement Pursuant to Section 14(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (Amendment No. ) Filed by the Registrant x Filed by a Party other than the Registrant o Check the appropriate box: o Preliminary Proxy Statement o Confidential, for Use of the Commission Only (as permitted by Rule 14a-6(e)(2)) x Definitive Proxy Statement o Definitive Additional Materials o Soliciting Material Pursuant to Rule §240.14a-12 CARNIVAL CORPORATION CARNIVAL PLC (Name of Registrant as Specified In Its Charter) (Name of Person(s) Filing Proxy Statement, if other than the Registrant) Payment of Filing Fee (Check the appropriate box): x No fee required. o Fee computed on table below per Exchange Act Rules 14a-6(i)(1) and 0-11. 1. Title of each class of securities to which transaction applies: 2. Aggregate number of securities to which transaction applies: 3. Per unit price or other underlying value of transaction computed pursuant to Exchange Act Rule 0-11 (set forth the amount on which the filing fee is calculated and state how it was determined): 4. Proposed maximum aggregate value of transaction: 5. Total fee paid: SEC 1913 (03-04) Persons who are to respond to the Collection of information contained in this form are not required to respond unless the form displays a currently valid OMB cotrol number. o Fee paid previously with preliminary materials. -

GF Capital Outturn Appendix 3

Appendix 3 Revised Estimates 2012/13 Scheme Description Original Slippage Rephasing Revised Budget Budget 2012/13 2012/13 £000's £000's £000's £000's Adult Social Care & Health R9235 SDS Freemantle - Phase 2 0 11 0 11 R9265 SDS Modernisation Woolston Comm Centre 593 44 0 637 R9310 Mental Health Scheme (R9310) 0 1 0 1 R9330 National Care Standards and H&S Work 80 227 0 307 R9340 Replacement of Appliances and Equipment 468 41 0 509 R9500 IT Infrastructure Grant 0 17 0 17 R9700 Common Assessment Framework 307 73 0 380 R9710 SCRG Capital - Transforming Adult Social Care 0 7 0 7 R9720 Residential Homes fabric furnishing CQC 0 364 0 364 R9730 Sembal House Refurbishment 257 0 (5) 252 1,705 785 (5) 2,485 Appendix 3 Revised Estimates 2012/13 Scheme Description Original Slippage Rephasing Revised Budget Budget 2012/13 2012/13 Children's Services E3001 Houndwell Park Play Area 326 15 0 341 E3004 Peartree Green Play Area 0 8 0 8 E3005 Fencing at Thornhill APG 0 1 0 1 E3006 Albany Road Play Area 72 0 0 72 E3007 Freemantle Common Play Area 13 0 0 13 E3008 Imber Way Play Area 0 36 0 36 E3009 Portswood RG Play Area 27 0 0 27 E3010 Saltmede Estate Play Area 0 36 0 36 E4045 Learningland Day Nursery 0 1 0 1 E4057 Childrens Centres Phase 3 Retentions 0 41 0 41 E5001 Primary Review Phase 2 0 26 0 26 E5002 Primary Review P2 - Bassett Green Primary School 0 13 0 13 E5004 Primary Review P2 - Kanes Hill Primary School 250 0 (34) 216 E5005 Primary Review P2 - Shirley Warren Primary 400 0 (49) 351 E5006 Primary Review P2 - Glenfield Infant School 100 0 (21) 79 -

Stop Message Magazine Issue 19 – April 2016

Issue 19 - April 2016 STOP MESSAGE The magazine of the Hampshire Fire and Rescue Service Past Members Association www.xhfrs.org.uk Make Pumps 10, HMS Collingwood 15 October 1976 Inside... SPECIAL BUMPERGuess who becameEDITION! a trucker? EATING IN THE FIFTIES Oil was for lubricating, fat was for cooking. Tea was made in a teapot using tea leaves and never green. Sugar enjoyed a good press in those days, and was regarded as being white gold. Cubed sugar was regarded as posh. Fish didn’t have fingers in those days. Eating raw fish was called poverty, not sushi. None of us had ever heard of yoghurt. Healthy food consisted of anything edible. People who didn’t peel potatoes were regarded as lazy. Pasta was not eaten in New Zealand. Indian restaurants were only found in India. Curry was a surname. Cooking outside was called camping. A takeaway was a mathematical problem. Seaweed was not a recognised food. A pizza was something to do with a leaning “Kebab” was not even a word, never mind a tower. food. All potato chips were plain; the only choice we Prunes were medicinal. had was whether to put the salt on or not. Surprisingly, muesli was readily available, it Rice was only eaten as a milk pudding. was called cattle feed. Calamari was called squid and we used it as Water came out of the tap. If someone had fish bait. suggested bottling it and charging more than petrol for it , they would have become a A Big Mac was what we wore when it was laughing stock!! raining. -

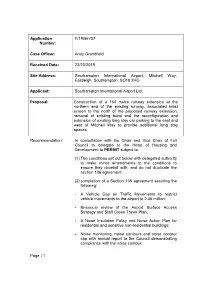

Planning Application

Application F/19/86707 Number: Case Officer: Andy Grandfield Received Date: 22/10/2019 Site Address: Southampton International Airport, Mitchell Way, Eastleigh, Southampton, SO18 2HG Applicant: Southampton International Airport Ltd. Proposal: Construction of a 164 metre runway extension at the northern end of the existing runway, associated blast screen to the north of the proposed runway extension, removal of existing bund and the reconfiguration and extension of existing long stay car parking to the east and west of Mitchell Way to provide additional long stay spaces Recommendation: In consultation with the Chair and Vice Chair of Full Council to delegate to the Head of Housing and Development to PERMIT subject to: (1) The conditions set out below with delegated authority to make minor amendments to the conditions to ensure they dovetail with, and do not duplicate the section 106 agreement. (2) completion of a Section 106 agreement securing the following: - A Vehicle Cap on Traffic Movements to restrict vehicle movements to the airport to 2.45 million; - Bi-annual review of the Airport Surface Access Strategy and Staff Green Travel Plan; - A Noise Insulation Policy and Noise Action Plan for residential and sensitive non-residential buildings; - Noise monitoring, noise contours and noise contour cap with annual report to the Council demonstrating compliance with the noise contour; Page | 1 - Air Quality Strategy; - Health Strategy including Community Health Fund; - Carbon Strategy; - Ecological Management and Mitigation to include Air Quality monitoring; - Construction Employment and Skills Plan; - Operational Employment and Skills Plan; - Safeguarding of the route of the proposed Chickenhall Lane Link Road; - Revoking of previous S106 Agreements and inclusion of previous restrictive obligations within a new agreement including restrictions on night time flying, engine testing, 20 ATMs within 0600 – 0700, reverse thrust, noise cap contour. -

Towards an International City of Culture

Towards an International City of Culture Southampton City Council Arts and Heritage Strategic Vision Executive Summary This Strategic Vision defines Southampton City Council’s strategic role regarding Arts and Heritage provision within the wider context of the City of Southampton Strategy towards 2026, council priorities, the Southampton Heritage and Arts People initiative (SHAPe), and the sub-regional Partnership for Urban South Hampshire (PUSH). Southampton is a thriving and growing city with a diverse and dynamic population. However, these developments are in pockets and other parts of the city (economically, physically, socially) remain significantly deprived. We want to transform Southampton from being a gateway to a place of destination where people want to visit, put down roots and engage in community. The City has a fantastic opportunity over the next twenty years to transform its cultural offer and create an overall vibrant cultural soul, a sense of identity and uniqueness that connects people to each other and to Southampton as place. Its rich cultural makeup, internationally important heritage story and nationally dynamic arts and creative scene provide an inspirational resource for exploitation. The significance of Southampton within the Partnership for Urban South Hampshire (PUSH) regional development area will ensure that this potential can be realised particularly within the context of Living Places. Culture is critical to Southampton’s economic development, health and wellbeing and the creation of an attractive image of the city as a place in which people want to live, work and play. Without a vibrant cultural soul, Southampton becomes a divided, anonymous, modern and transient settlement with little civic pride or unique sense of place, and without an attractive, sustainable and stimulating environment that people value. -

Capital Outturn 0708

ITEM NO 19 (iii) Appendix 1 Capital Outturn 2007/08 Revised Estimates 2008/09 for Slippage and Rephasing Approved Recommended Estimate Estimate 2008/09 Slippage Rephasing 2008/09 £000 £000 £000 £000 Children's Services E7075 Freemantle Nursery Children's Centre 267 99 0 366 E7076 Shirley Warren Nursery Children's Centre 14 0 -11 3 E7078 Woolston Community P.Schl Children's Ctr 0 93 0 93 E7079 Woolston Infant Children's Centre 0 150 0 150 E8051 Shirley Warren Children's Centre 0 4 0 4 E8052 Harefield Primary Children's Centre 714 2 0 716 E8053 Startpoint Sholing Children's Centre 0 4 0 4 E8054 Thornhill Healthy Living Children's Ctre 0 1 0 1 E8055 Merry Community Children's Centre 0 16 0 16 E8056 Fairisle Junior Children's Centre 298 55 0 353 E9071 Thornhill Primary Children's Centre 439 234 0 673 E9072 Townhill Junior Children's Centre 364 294 0 658 E9073 Fairisle Infants Children's Centre 178 2 0 180 E9074 Swaythling Primary Children's Centre 0 46 0 46 E9075 Portswood Primary Children's Centre 0 55 0 55 E9077 The Avenue Centre 0 8 0 8 E9078 Childrens Centre Small Projects 63 27 0 90 E9079 Childrens Centre Capital Grants 1,359 0 -111 1,248 E9082 Extended Schools Funding 2008-11 330 0 0 330 E9083 Early Years Capital Grant 2008-2011 931 0 0 931 E6000 Youth Capital Fund 120 46 0 166 E6720 Closure Of Highcrown St (Highfield Schl) 238 0 -13 225 E7060 Ndc - Hightown, K.Hill & Thornhill Schls 0 463 0 463 E7061 Playways Scheme - Thornhill Plus You 225 0 0 225 E8100 Grove Park MUGA 20 219 0 239 E8110 Bitterne Family Centre - Refurbishment 0 3 -

Stop Message Magazine Issue 22

Issue 22 - October 2018 STOP MESSAGE https://xhfrs.wordpress.com The magazine of the Hampshire Fire and Rescue Service Past Members Association Water supply running low, Stanswood Farm, Calshot 17 August 1979 INSIDE East Street Fred Gardiner PAST TIMES Bombing A personal experience Focus on 17th December 1978 part 3 Romsey Station World War 2 UK Propaganda Posters 1939 Keep Calm and Carry On 1939-45 What I Know - I Keep To Myself 1941 Lester Beall Careless Talk Costs Lives British propaganda during World War 2: Britain recreated the World War I Ministry of Information for the duration of World War II to generate propaganda to influence the population towards support for the war effort. A wide range of media was employed aimed at local and overseas audiences. Traditional forms of media such as newspapers and posters were joined by new media, including cinema (film), newsreels, and radio. A wide range of themes were addressed, fostering hostility to towards the enemy, support for the allies, and specific pro-war projects such as conserving metal, waste, and growing vegetables. Propaganda was deployed to encourage people to volunteer for onerous or dangerous war work, such as factories of in the Home Guard. Male conscription ensured that general recruitment posters were not needed, but specialist services posters did exist, and many posters aimed at women, such as the Land Army or the ATS. Posters were also targeted at increasing production. Pictures of the Armed Forces often called for support from civilians, and posters juxtaposed civilian workers and soldiers to urge that the forces were relying on them, and to instruct hem in the importance of their role. -

Ebook Download the Final Cut Ebook

THE FINAL CUT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Michael Dobbs | 480 pages | 09 Apr 2010 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007375158 | English | London, United Kingdom The Final Cut ( film) - Wikipedia Trailers and Videos. Crazy Credits. Alternate Versions. Rate This. Episode Guide. In order to secure his retirement and establish Available on Amazon. Added to Watchlist. Top-Rated Episodes S1. Error: please try again. The Best Horror Movies on Netflix. Magnus wants to watch. DomProMedia - Series Complete. Use the HTML below. You must be a registered user to use the IMDb rating plugin. Episodes Seasons. Edit Cast Series cast summary: Ian Richardson Francis Urquhart 4 episodes, Diane Fletcher Elizabeth Urquhart 4 episodes, Paul Freeman Tom Makepeace 4 episodes, Isla Blair Claire Carlsen 4 episodes, Nickolas Grace Geoffrey Booza Pitt 4 episodes, Glyn Grain Rayner 4 episodes, Nick Brimble Corder 4 episodes, Dorothy Vernon Speaker 4 episodes, Andrew Seear Wolfin 4 episodes, Peter Symonds Polecutt 4 episodes, John Rowe Sir Clive Watling 3 episodes, Yolanda Vazquez Maria Passolides 3 episodes, Duggie Brown Joe Badger 3 episodes, Kevork Malikyan Nures 2 episodes, David Ryall Sir Bruce Bullerby 2 episodes, Joseph Long President Nicolaou 2 episodes, Cherith Mellor Hilary Makepeace 2 episodes, Erika Hoffman Princess 2 episodes, Leon Lissek Evanghelos Passolides 2 episodes, Tom Beasley Young King 2 episodes, Richard Bebb Political Commentator 2 episodes, Sue Edelson Newsreader 2 episodes, David Ashford Edit Storyline Francis Urquhart is too experienced a politician not to know that everything must end, even his long career as British prime minister. Genres: Drama. Edit Did You Know? Trivia Michael Dobbs , the author of the original book, was angered at the opening scene depicting Margaret Thatcher 's funeral. -

Southampton's Migrant Past

SOUTHAMPTON’S MIGRANT PAST A WALKING TOUR This pamphlet and the walking tour are to introduce you to the rich history of Southampton’s migrant past. Southampton, even from prehistory, has been shaped by migration – both through invasion (Romans, Saxon, Viking and Norman) and by refugees and others who have chosen to come or have been sent here, making it the exciting cosmopolitan city it is today. Much of this migrant past is hidden but can still be found. This is typified by the cover illustration – the wonderful automata Bathers in Southampton Water by Sam Smith. Sam, the son of a steamship captain, grew up in Southampton and used to watch the liners go by, impressed as a lad only by the number and size of their funnels. Later in life after visiting Ellis Island in New York he realised that they were vessels carrying thousands of ordinary migrants. In this work, Sam Smith tells the user of this model that in the bowels of the ship ‘you may espy the Steerage Passengers’. These, he believed, were ‘the real people’. Similarly this walking tour will make ‘the invisible, visible’ so that the migrant contribution can be fully appreciated - not only for those who live here but also to visitors to Southampton. Southampton, past and present, is a place of movement and settlement. This tour is designed to show that its dynamism is built on migration. We hope you enjoy exploring these exciting sites which will concentrate on the historic quarter and the old dock area. A separate tour of the old Cemetery - over a mile to the north - is also provided, revealing again the fascinating and unique histories of migrant Southampton. -

Signature Sounds Available

Guitar Pro 7: Signature Sounds available STEEL GUITAR America A Horse with no Name America Apologies All Apologies Nirvana Babe Babe I'm Gonna Leave You Led Zeppelin Blue Eyes Behind Blue Eyes Limp Bizkit Bron Bron Yr Aur Led Zeppelin California California Joni Mitchell Cat Father and Son Cat Stevens Clap The Clap Yes Cross Road Cross Road Blues Robert Johnson Drake Road Road Nick Drake Dreamin California Dreamin' The Mamas and the Papas Drive Drive Incubus Dylan Bob Dylan Extreme More Than Words Extreme Fade Fade to Black Metallica Fans Fans Kings of Leon Frizz Moon River Bill Frisell Gently While My Guitar Gently Weeps The Beatles Goodbye Last Goodbye Jeff Buckley Greensleeves Greensleeves Jeff Beck Harper Sexuel Healing Ben Harper Jessica Jessica The Allman Bothers Band Joni A Case of You Joni Mitchell Life 18 and Life Skid Row Long Train Long Train Running The Doobie Brothers Mainstreet Mainstreet Breakdown Chet Atkins My Mind Where Is My Mind The Pixies 1 No Rain No Rain Blind Melon November November Rain Guns 'N Roses Old Man Old Man Neil Young Overnight Overnight Bag Rory Gallagher Pinball Pinball Wizard The Who Presence Dear God Avenged Sevenfold Redemption Redemption Song Bob Marley Revolution Talkin 'Bout a Revolution Tracy Chapman Road Road Nick Drake September Ends Wake Me Up When September Ends Green Day Sixteen Tons Sixteen Tons Merle Travis Sky Eye Eye in the Sky Alan Pasons Project Sleep The Sleep Pantera Stairway Stairway to Heaven Led Zeppelin Stomp Bron-Y-Aur Stomp Led Zeppelin Summer All Summer Long Kid Rock Theater