ABSTRACT Education in the Thought and Theology of Jorge Mario

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018 Conforming to General Convention 2018 1 Preface Christians have since ancient times honored men and women whose lives represent heroic commitment to Christ and who have borne witness to their faith even at the cost of their lives. Such witnesses, by the grace of God, live in every age. The criteria used in the selection of those to be commemorated in the Episcopal Church are set out below and represent a growing consensus among provinces of the Anglican Communion also engaged in enriching their calendars. What we celebrate in the lives of the saints is the presence of Christ expressing itself in and through particular lives lived in the midst of specific historical circumstances. In the saints we are not dealing primarily with absolutes of perfection but human lives, in all their diversity, open to the motions of the Holy Spirit. Many a holy life, when carefully examined, will reveal flaws or the bias of a particular moment in history or ecclesial perspective. It should encourage us to realize that the saints, like us, are first and foremost redeemed sinners in whom the risen Christ’s words to St. Paul come to fulfillment, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” The “lesser feasts” provide opportunities for optional observance. They are not intended to replace the fundamental celebration of Sunday and major Holy Days. As the Standing Liturgical Commission and the General Convention add or delete names from the calendar, successive editions of this volume will be published, each edition bearing in the title the date of the General Convention to which it is a response. -

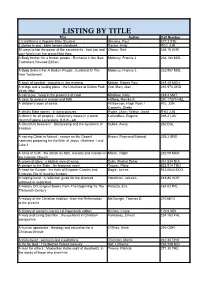

Parish Library Listing

LISTING BY TITLE Title Author Call Number 2 Corinthians (Lifeguide Bible Studies) Stevens, Paul 227.3 STE 3 stories in one : bible heroes storybook Rector, Andy REC JUN 50 ways to tap the power of the sacraments : how you and Ghezzi, Bert 234.16 GHE your family can live grace-filled lives A Body broken for a broken people : Eucharist in the New Moloney, Francis J. 234.163 MOL Testament Revised Edition A Body Broken For A Broken People : Eucharist In The Moloney, Francis J. 232.957 MOL New Testament A book of comfort : thoughts in late evening Mohan, Robert Paul 248.48 MOH A bridge and a resting place : the Ursulines at Dutton Park Ord, Mary Joan 255.974 ORD 1919-1980 A call to joy : living in the presence of God Matthew, Kelly 248.4 MAT A case for peace in reason and faith Hellwig, Monika K. 291.17873 HEL A children's book of saints Williamson, Hugh Ross / WIL JUN Connelly, Sheila A child's Bible stories : in living pictures Ryder, Lilian / Walsh, David RYD JUN A church for all peoples : missionary issues in a world LaVerdiere, Eugene 266.2 LAV church Eugene LaVerdiere, S.S.S - edi A Church to believe in : Discipleship and the dynamics of Dulles, Avery 262 DUL freedom A coming Christ in Advent : essays on the Gospel Brown, Raymond Edward 226.2 BRO narritives preparing for the Birth of Jesus : Matthew 1 and Luke 1 A crisis of truth - the attack on faith, morality and mission in Martin, Ralph 282.09 MAR the Catholic Church A crown of glory : a biblical view of aging Dulin, Rachel Zohar 261.834 DUL A danger to the State : An historical novel Trower, Philip 823.914 TRO A heart for Europe : the lives of Emporer Charles and Bogle, James 943.6044 BOG Empress Zita of Austria-Hungary A helping hand : A reflection guide for the divorced, Horstman, James L. -

Evangelii Gaudium the Joy of the Gospel by Pope Francis

EVANGELII GAUDIUM THE JOY OF THE GOSPEL BY POPE FRANCIS Prepared by Fr. James Swanson, LC RCSpirituality.org Produced by Coronation coronationmedia.com OVERVIEW EVANGELII GAUDIUM: THE JOY OF THE GOSPEL SUMMARY WHO CAN PARTICIPATE? This Study Circle Guide provides an avenue for in- Papal documents are usually dense and written from a depth study of Pope Francis’s Apostolic Exhortation, point of view that assumes a lot of basic knowledge of Evangelii Gaudium—The Joy of the Gospel. This is the the faith. Therefore, it’s a good idea to study this in a Holy Father’s programmatic document. To understand group setting in which the various participants are in a it is to understand how he sees his mission as pope – similar place in their own faith journey. and therefore our mission as Catholic Christians – in this moment of Church history. Any Catholic interested in going deeper in their knowledge of the Church and their understanding of Pope Francis’s vision will benefit from this Guide. Non- CATEGORIES OF INTEREST Catholics should understand that the basics of the Catholic faith are assumed by the Holy Father – he does Catholic Doctrine; Prayer and Spiritual Growth; not try to explain them all in the Exhortation. Apostolate The sections on “Questions for Personal Reflection or Group Discussion” contain numerous references to the Regnum Christi Member’s Handbook. Participants RECOMMENDED NUMBER OF SESSIONS who are not members of (or familiar with) the ecclesial The Study Circle Guide contains 6 sessions. Session #1 Movement Regnum Christi may find little interest in corresponds to the Exhortation’s introduction, which these questions. -

What Is an Apostolic Exhortation? It's a Papal Document That Exhorts

‘Evangelii Gaudium’ and ‘Laudato Si’ All creation “groans in travail” (Rom 8:22) How are we called to a deeper conversion? What is an apostolic exhortation? A papal document that encourages the faithful to implement a particular aspect of the Church’s life and teaching. What is an encyclical? A part of the ordinary magisterium (teaching authority) of the Church Evangelii Gaudium (English: The Joy of the Gospel) is a 2013 apostolic exhortation by Pope Francis on "the church's primary mission of evangelization in the modern world." Evangelii Gaudium What is Pope Francis’ main message in Evangelii Gaudium? The principal theme involves the need for a joyful proclamation of the Gospel to the entire world. “…an Apostolic Exhortation written around the theme of Christian joy in order that the Church may rediscover the original source of evangelisation in the contemporary world” In Evangelii Gaudium Pope Francis’ expresses: Concern that the Church is becoming more judgmental than merciful. He wants a Church that has the outgoing spirit of the pilgrim, as opposed to a Church closed in on itself, languishing in ‘institutional inertia’ He worries that some Catholics have become too attached to the external forms of the faith, while their hearts have grown cold. 6 insights provided by Pope Francis, in EG: 1 God’s inexhaustible mercy. 2 The way of beauty. 3 The ‘revolution of tenderness.’ 4 Humility before Scripture. 5 The wounds of Christ. 6 ‘Faith is always a cross.’ God’s inexhaustible mercy. We are called to renew our commitment to mercy as an external work “The Eucharist, although it is the fullness of sacramental life, is not a prize for the perfect but a powerful medicine and nourishment for the weak.” The way of beauty. -

We Are Pleased and Honored to Welcome You to St. Francis of Assisi Parish

We are pleased and honored Military Service Honor Roll To welcome you to LCPL Alex Bielawa, U.S. Marines Lt. Colonel William J. Girard, U.S. Army St. Francis of Assisi Parish Sgt. Derek Keegan, U.S. Army 67 West Town Street, Lebanon, CT 06249 Major Michael A. Goba, U.S. Army JAG Telephone: 860.642.6711 Fax: 860.642.4032 E-5 Francis Orcutt, U.S. Army HMC Heather S. Gardipee, U.S. Navy Rev. Mark Masnicki, Pastor Pvt. Zachary Berquist, U.S. Army Rev. Benjamin Soosaimanickam, Parochial Vicar Pvt. First Class Jacob Grzanowicz Deacon Michael Puscas Sgt. Justin A. VonEdwins, U.S. Army Sgt. Robert Massicotte U.S. Army 1st Lt. Miles N. Snelgrove USMC 2 nd Batt. 6 th Marines Airman Emerson Flannery, U.S. Navy Saturday June 25, 2016 Blessed Virgin Mary Prayer for our Men and Women in Military Service 4:00 PM Confessions 5:00 PM For the Souls in Purgatory O Prince of Peace, we humbly ask Your protection for all our Sunday, June 26, 2016 13th Sunday in Ordinary Time men and women in military service. Give them unflinching 8:00 AM People of the parish living & deceased courage to defend with honor, dignity, and devotion the rights of 10:30 AM Bert & Rachel Bosse 55 th wedding anniversary all who are imperiled by injustice and evil. Guard our churches, Monday June 27, 2016 St. Cyril of Alexandria, bishop, doctor our homes, our schools, our hospitals, our factories, our of the Church buildings and all those within from harm and peril. Protect our NO MASS land and its peoples from enemies within and without. -

The Holy See (Including Vatican City State)

COMMITTEE OF EXPERTS ON THE EVALUATION OF ANTI-MONEY LAUNDERING MEASURES AND THE FINANCING OF TERRORISM (MONEYVAL) MONEYVAL(2012)17 Mutual Evaluation Report Anti-Money Laundering and Combating the Financing of Terrorism THE HOLY SEE (INCLUDING VATICAN CITY STATE) 4 July 2012 The Holy See (including Vatican City State) is evaluated by MONEYVAL pursuant to Resolution CM/Res(2011)5 of the Committee of Ministers of 6 April 2011. This evaluation was conducted by MONEYVAL and the report was adopted as a third round mutual evaluation report at its 39 th Plenary (Strasbourg, 2-6 July 2012). © [2012] Committee of experts on the evaluation of anti-money laundering measures and the financing of terrorism (MONEYVAL). All rights reserved. Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, save where otherwise stated. For any use for commercial purposes, no part of this publication may be translated, reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic (CD-Rom, Internet, etc) or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system without prior permission in writing from the MONEYVAL Secretariat, Directorate General of Human Rights and Rule of Law, Council of Europe (F-67075 Strasbourg or [email protected] ). 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. PREFACE AND SCOPE OF EVALUATION............................................................................................ 5 II. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY....................................................................................................................... -

Integrating Ecology and Justice: the New Papal Encyclical by Mary Evelyn Tucker and John Grim

Feature Integrating Ecology and Justice: The New Papal Encyclical by Mary Evelyn Tucker and John Grim Mat McDermott Una Terra Una Famiglia Humana, One Earth One Family climate march in Vatican City in June 2015. In Brief In June of 2015, Pope Francis released the first encyclical on ecology. The Pope’s message highlights “integral ecology,” intrinsically linking ecological integrity and social justice. While the encyclical notes the statements of prior Popes and Bishops on the environment, Pope Francis has departed from earlier biblical language describing the domination of nature. Instead, he expresses a broader understanding of the beauty and complexity of nature, on which humans fundamentally depend. With “integral ecology” he underscores this connection of humans to the natural environment. This perspective shifts the climate debate to one of a human change of consciousness and conscience. As such, the encyclical has the potential to bring about a tipping point in the global community regarding the climate debate, not merely among Christians, but to all those attending to this moral call to action. 38 | Solutions | July-August 2015 | www.thesolutionsjournal.org n June 18, 2015 Pope Francis thinking. By drawing on and develop- We can compare Pope Francis’ released Laudato Si, the first ing the work of earlier theologians and thinking to the writing of Pope John encyclical in the history of ethicists, this encyclical makes explicit Paul II, who himself builds on Pope O Rerum the Catholic Church on ecology. An the links between social justice and Leo XIII’s progressive encyclical encyclical is the highest-level teaching eco-justice.1 Novarum on workers’ rights in 1891. -

0.GEMATRIA DATABASE.Pages

GEMATRIA - DATABASE ! Bavarian Illuminati Est. May 1st, 1776} 5/01/1776 ! Scottish Rite Est. May 31, 1801 } 5/31/1801 Knights Templar ARRESTED on Oct. 13, 1307 } 10/12/1307 ! Knights Templar FOUNDED in Jerusalem, Israel: 1119 ! Skull & Bones 322 FOUNDED in 1832 at Yale University) (Russell Trust Association - Parent Organization) 322 references 322 BC ! Vatican City Est. February 11, 1929 (109 acres) ! One legend is that the numbers in the society's emblem ("322") represent "founded in '32, 2nd corps", referring to a first Corps in an unknown German university.[22][23] ! Convocation founded in 1539 (3rd Papal Bull) Jesuits founded in 1541 Copernicus of 1543 (Ball Earth) The Council of Trent founded in 1545 ! (Christopher Columbus) America discovered in 1492 (2 Papal Bulls) 1912 = Titanic sank 1913 = Federal Reserve Established 1914 = First World War 1917 = Bolshevik Communist Invasion ! Jewish Bolshevism, also known as Judeo-Bolshevism, is an antisemitic and anti-communist canard [citation needed] which alleges that the Jews were at the origin of the Russian Revolution and held the primary power among Bolsheviks. Similarly, the Jewish Communism theory implies that Jews have been dominating the Communist movements in the world. It is similar to the ZOG conspiracy theory, which asserts that Jews control world politics. The expressions have been used as a catchword for the assertion that Communism is a Jewish conspiracy. ! Hexagram = Star of David ! Pythagoras the Samian or Pythagoras of Samos (570-495 BC) was a mathematician, Ionian Greek -

The New Organization of the Catholic Church in Romania

Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe Volume 12 Issue 2 Article 4 3-1992 The New Organization of the Catholic Church in Romania Emmerich András Hungarian Institute for Sociology of Religion, Toronto Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, and the Eastern European Studies Commons Recommended Citation András, Emmerich (1992) "The New Organization of the Catholic Church in Romania," Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe: Vol. 12 : Iss. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree/vol12/iss2/4 This Article, Exploration, or Report is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NEW ORGANIZATION OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN ROMANIA by Emmerich Andras Dr. Emmerich Andras (Roman Catholic) is a priest and the director of the Hungarian Institute for Sociology of Religion in Vienna. He is a member of the Board of Advisory Editors of OPREE and a frequent previous contributor. I. The Demand of Catholics in Transylvania for Their Own Church Province Since the fall of the Ceausescu regime, the 1948 Prohibition of the Greek Catholic Church in Romania has been lifted. The Roman Catholic Church, which had been until then tolerated outside of the law, has likewise obtained legal status. During the years of suppression, the Church had to struggle to maintain its very existence; now it is once again able to carry out freely its pastoral duties. -

THE CORE THEMES of the ENCYCLICAL FRATELLI TUTTI St

THE CORE THEMES OF THE ENCYCLICAL FRATELLI TUTTI St. John Lateran, 15 November 2020 Card. GIANFRANCO RAVASI Preamble Let us begin from a spiritual account drawn from Tibetan Buddhism, a different world from that of the encyclical, but significant nonetheless. A man walks alone on a desert track that dissolves into the distance on the horizon. He suddenly realises that there is another being, difficult to make out, on the same path. It may be a beast that inhabits these deserted spaces; the traveller’s heart beats faster and faster out of fear, as the wilderness does not offer any shelter or help, so he must continue to walk. As he advances, he discerns the profile: a man’s. However, fear does not leave him; in fact, that man could be a fierce bandit. He has no choice but to go on, as the fear of an assault grips his soul. The traveller no longer has the courage to look up. He can hear the other man’s steps approaching. The two men are now face to face: he looks up and stares at the person before him. In his surprise he cries out: “This is my brother whom I haven’t seen for many years!” We wish to refer to this ancient parable from a different religion and culture at the beginning of this presentation to show that the yearning pervading Pope Francis’s new encyclical Fratelli tutti is an essential component of the spiritual breadth of all humanity. In fact, we find a few unexpected “secular” quotations in the text, such as the 1962 album Samba da Bênção by Brazilian poet and musician Vinicius de Moraes (1913-1980) in which he sang: “Life, for all its confrontations, is the art of encounter” (n. -

Why Vatican II Happened the Way It Did, and Who’S to Blame

SPECIAL EDITION SUMMER 2017 Dealing frankly with a messy pontificate, without going off the rails No accidents: why Vatican II happened the way it did, and who’s to blame Losing two under- appreciated traditionalists Bishops on immigration: why can’t we call them what they are? $8.00 Publisher’s Note The nasty personal remarks about Cardinal Burke in a new EDITORIAL OFFICE: book by a key papal advisor, Cardinal Maradiaga, follow a pattern PO Box 1209 of other taunts and putdowns of a sitting cardinal by significant Ridgefield, Connecticut 06877 cardinals like Wuerl and even Ouellette, who know that under [email protected] Pope Francis, foot-kissing is the norm. And everybody half- Your tax-deductible donations for the continu- alert knows that Burke is headed for Church oblivion—which ation of this magazine in print may be sent to is precisely what Wuerl threatened a couple of years ago when Catholic Media Apostolate at this address. he opined that “disloyal” cardinals can lose their red hats. This magazine exists to spotlight problems like this in the PUBLISHER/EDITOR: Church using the print medium of communication. We also Roger A. McCaffrey hope to present solutions, or at least cogent analysis, based upon traditional Catholic teaching and practice. Hence the stress in ASSOCIATE EDITORS: these pages on: Priscilla Smith McCaffrey • New papal blurtations, Church interference in politics, Steven Terenzio and novel practices unheard-of in Church history Original logo for The Traditionalist created by • Traditional Catholic life and beliefs, independent of AdServices of Hollywood, Florida. who is challenging these Can you help us with a donation? The magazine’s cover price SPECIAL THANKS TO: rorate-caeli.blogspot.com and lifesitenews.com is $8. -

Ave Papa Ave Papabile the Sacchetti Family, Their Art Patronage and Political Aspirations

FROM THE CENTRE FOR REFORMATION AND RENAISSANCE STUDIES Ave Papa Ave Papabile The Sacchetti Family, Their Art Patronage and Political Aspirations LILIAN H. ZIRPOLO In 1624 Pope Urban VIII appointed Marcello Sacchetti as depositary general and secret treasurer of the Apostolic Cham- ber, and Marcello’s brother, Giulio, bishop of Gravina. Urban later gave Marcello the lease on the alum mines of Tolfa and raised Giulio to the cardinalate. To assert their new power, the Sacchetti began commissioning works of art. Marcello discov- ered and promoted leading Baroque masters, such as Pietro da Cortona and Nicolas Poussin, while Giulio purchased works from previous generations. In the eighteenth century, Pope Benedict XIV bought the collection and housed it in Rome’s Capitoline Museum, where it is now a substantial portion of the museum’s collection. By focusing on the relationship between the artists in ser- vice and the Sacchetti, this study expands our knowledge of the artists and the complexity of the processes of agency in the fulfillment of commissions. In so doing, it underlines how the Sacchetti used art to proclaim a certain public image and to announce Cardinal Giulio’s candidacy to the papal throne. ______ copy(ies) Ave Papa Ave Papabile Payable by cheque (to Victoria University - CRRS) ISBN 978-0-7727-2028-2 or by Visa/Mastercard $24.50 Name as on card ___________________________________ (Outside Canada, please pay in US $.) Visa/Mastercard # _________________________________ Price includes applicable taxes. Expiry date _____________ Security code ______________ Send form with cheque/credit card Signature ________________________________________ information to: Publications, c/o CRRS Name ___________________________________________ 71 Queen’s Park Crescent East Address __________________________________________ Toronto, ON M5S 1K7 Canada __________________________________________ The Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies Victoria College in the University of Toronto Tel: 416-585-4465 Fax: 416-585-4430 [email protected] www.crrs.ca .