Nepal (FFE-367-2014/050-00) January 2015 – September 2016 Evaluation Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Food Security Bulletin 29

Nepal Food Security Bulletin Issue 29, October 2010 The focus of this edition is on the Mid and Far Western Hill and Mountain region Situation summary Figure 1. Percentage of population food insecure* 26% This Food Security Bulletin covers the period July-September and is focused on the Mid and Far Western Hill and Mountain (MFWHM) 24% region (typically the most food insecure region of the country). 22% July – August is an agricultural lean period in Nepal and typically a season of increased food insecurity. In addition, flooding and 20% landslides caused by monsoon regularly block transportation routes and result in localised crop losses. 18 % During the 2010 monsoon 1,600 families were reportedly 16 % displaced due to flooding, the Karnali Highway and other trade 14 % routes were blocked by landslides and significant crop losses were Oct -Dec Jan-M ar Apr-Jun Jul-Sep Oct -Dec Jan-M ar Apr-Jun Jul-Sep reported in Kanchanpur, Dadeldhura, western Surkhet and south- 08 09 09 09 09 10 10 10 eastern Udayapur. NeKSAP District Food Security Networks in MFWHM districts Rural Nepal Mid-Far-Western Hills&Mountains identified 163 VDCs in 12 districts that are highly food insecure. Forty-four percent of the population in Humla and Bajura are reportedly facing a high level of food insecurity. Other districts with households that are facing a high level of food insecurity are Mugu, Kalikot, Rukum, Surkhet, Achham, Doti, Bajhang, Baitadi, Dadeldhura and Darchula. These households have both very limited food stocks and limited financial resources to purchase food. Most households are coping by reducing consumption, borrowing money or food and selling assets. -

Feasibility Study of Kailash Sacred Landscape

Kailash Sacred Landscape Conservation Initiative Feasability Assessment Report - Nepal Central Department of Botany Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur, Nepal June 2010 Contributors, Advisors, Consultants Core group contributors • Chaudhary, Ram P., Professor, Central Department of Botany, Tribhuvan University; National Coordinator, KSLCI-Nepal • Shrestha, Krishna K., Head, Central Department of Botany • Jha, Pramod K., Professor, Central Department of Botany • Bhatta, Kuber P., Consultant, Kailash Sacred Landscape Project, Nepal Contributors • Acharya, M., Department of Forest, Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation (MFSC) • Bajracharya, B., International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) • Basnet, G., Independent Consultant, Environmental Anthropologist • Basnet, T., Tribhuvan University • Belbase, N., Legal expert • Bhatta, S., Department of National Park and Wildlife Conservation • Bhusal, Y. R. Secretary, Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation • Das, A. N., Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation • Ghimire, S. K., Tribhuvan University • Joshi, S. P., Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation • Khanal, S., Independent Contributor • Maharjan, R., Department of Forest • Paudel, K. C., Department of Plant Resources • Rajbhandari, K.R., Expert, Plant Biodiversity • Rimal, S., Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation • Sah, R.N., Department of Forest • Sharma, K., Department of Hydrology • Shrestha, S. M., Department of Forest • Siwakoti, M., Tribhuvan University • Upadhyaya, M.P., National Agricultural Research Council -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

End Line Study of Sanitation, Hygiene and Water Management Project, Bajhang Final Report

End Line Study of Sanitation, Hygiene and Water Management Project, Bajhang Final Report Submitted to Nepal Red Cross Society Kathmandu By Chitra Bahadur Budhathoki, PhD Consultant June 2018 The Sanitation, Hygiene and Water Project is supported by the Australian Government through the Australian Red Cross and implemented by Nepal Red Cross Society. ii ACRONYMS ARC : Australian Red Cross BCC : Behaviour Change Communication CHAST : Child Hygiene and Sanitation Training CLTS : Community Led Total Sanitation DRR : Disaster Risk Reduction DWSS : Department of Water Supply and Sewerage D-WASH-CC : District WASH Coordination Committee FCHV : Female Community Health Volunteer FGD : Focus Group Discussion GoN : Government of Nepal IEC : Information, Education and Communication KPI : Key Performance Indicator MTR : Mid-Term Review NRCS : Nepal Red Cross Society PHAST : Participatory Hygiene and Sanitation Transformation ODF : Open Defecation Free RM : Rural Municipality R/M-WASH-CC : Rural/Municipality-Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene-Coordination Committee SHWM : Sanitation, Hygiene and Water Management VCA : Vulnerability and Capacity Assessment (VCA) VDC : Village Development Committee VMW : Village Maintenance Worker V-WASH-CC : Village WASH Coordination Committee WASH : Water Sanitation and Hygiene WHO : World Health Organization W-WASH-CC : Ward WASH Coordination Committee WSUC : Water and Sanitation User Committee WUC : Water Users Committee iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This study is an outcome of the collective efforts of the study team and many individuals and institutions. First, I wish to express my sincere gratitude to Nepal Red Cross Society/Australian Red Cross for entrusting me to carry out this study. I would like to thank Mukesh Singh, Amar Mani Poudel, Suvechhya Manandhar and Ganga Shreesh for their continual supports in the entire process of this study. -

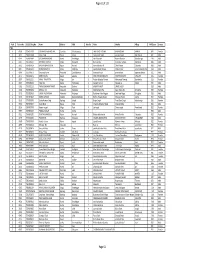

TSLC PMT Result

Page 62 of 132 Rank Token No SLC/SEE Reg No Name District Palika WardNo Father Mother Village PMTScore Gender TSLC 1 42060 7574O15075 SOBHA BOHARA BOHARA Darchula Rithachaupata 3 HARI SINGH BOHARA BIMA BOHARA AMKUR 890.1 Female 2 39231 7569013048 Sanju Singh Bajura Gotree 9 Gyanendra Singh Jansara Singh Manikanda 902.7 Male 3 40574 7559004049 LOGAJAN BHANDARI Humla ShreeNagar 1 Hari Bhandari Amani Bhandari Bhandari gau 907 Male 4 40374 6560016016 DHANRAJ TAMATA Mugu Dhainakot 8 Bali Tamata Puni kala Tamata Dalitbada 908.2 Male 5 36515 7569004014 BHUVAN BAHADUR BK Bajura Martadi 3 Karna bahadur bk Dhauli lawar Chaurata 908.5 Male 6 43877 6960005019 NANDA SINGH B K Mugu Kotdanda 9 Jaya bahadur tiruwa Muga tiruwa Luee kotdanda mugu 910.4 Male 7 40945 7535076072 Saroj raut kurmi Rautahat GarudaBairiya 7 biswanath raut pramila devi pipariya dostiya 911.3 Male 8 42712 7569023079 NISHA BUDHa Bajura Sappata 6 GAN BAHADUR BUDHA AABHARI BUDHA CHUDARI 911.4 Female 9 35970 7260012119 RAMU TAMATATA Mugu Seri 5 Padam Bahadur Tamata Manamata Tamata Bamkanda 912.6 Female 10 36673 7375025003 Akbar Od Baitadi Pancheswor 3 Ganesh ram od Kalawati od Kalauti 915.4 Male 11 40529 7335011133 PRAMOD KUMAR PANDIT Rautahat Dharhari 5 MISHRI PANDIT URMILA DEVI 915.8 Male 12 42683 7525055002 BIMALA RAI Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Man Bahadur Rai Gauri Maya Rai Ghodghad 915.9 Female 13 42758 7525055016 SABIN AALE MAGAR Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Raj Kumar Aale Magqar Devi Aale Magar Ghodghad 915.9 Male 14 42459 7217094014 SOBHA DHAKAL Dolakha GhangSukathokar 2 Bishnu Prasad Dhakal -

Government of Nepal

Government of Nepal District Transport Master Plan (DTMP) VOLUME – I MAIN REPORT Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development Department of Local Infrastructure Development and Agricultural Roads (DOLIDAR) District Development Committee, Bajhang January 2013 Submitted by (SIDeF) for the District Development Committee (DDC) and District Technical Office(DTO),Bajhang with Technical Assistance from the Department of Local Infrastructure and Agricultural Roads (DOLIDAR)Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development and grant supported by DFID.Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development and grant supported by DFID. Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development and grant supported by DFID i PREFACE / ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report on the of Preparation of District Transport Master Plan (DTMP) of Bajhang District has been prepared under the contract agreement between RTI SECTOR Maintenance Pilot for Office of District Development Committee, Bajhang District and SIDeF, Kathmandu. The consultant has prepared this report after extensive documentary consultation/ field work, road inventory study and interaction with stakeholders of the district. We would like to extend our heartfelt gratitude to the RTI SECTOR Maintenance Pilot for entrusting us to carry out this task and extend our thanks to all the team of RTI sector Maintenance for the cooperation and guidance in accomplishing the work. SIDeF would like to express our gratitude to Mr. Yuwaraj Kattel, Local Development Officer, Mr. Narendra K.C., Chief DTO, Mr.Lal Bahadur Thapa, Engineer, and all the DDC and DTO staffs for their valuable suggestions and co- operation for the preparation of this report. We also extend our sincere thanks to the representatives of political parties for their active and valuable participation in the process of DTMP preparation. -

GAFSP Nepal CSO Mission Report 2014-06 Final

Nepal Agriculture Food Security Project (AFSP) 6TH CSO MISSION May 9-14, 2014 REPORT Executive Summary The Mission was conducted by Mr. Raul Socrates Banzuela, the Alternate Asia CSO Representative to the GAFSP Steering Committee last May 9-14, 2014, hosted by All Nepal Peasant Federation Association (ANPFA). The key objective of the mission was to get updates on the Nepal Agriculture and Food Security Project and the roles played by CSOs in project implementation. The mission included review of literature; field visit to Bahjhang District and meetings with staff of District Agricultural and Livestock Offices, sub-center, and farmer technician and farmer leaders; meetings with leaders of CSOs which included ANPFA (All Nepal Peasant Federation Association), CSRC (Community Self Reliance Center) and NLRF (National Land Rights Forum-Nepal) ; the Project Head, FAO Team Leader, and the WB's Sr. Rural Development Specialist (co-TTL). The Mission found the Project at its start up phase with both managers and implementers feeling upbeat and excited that after three years, the project had eventually taken off and started the learning stage. The key expected outcomes from the Project are: (i) increase in the productivity of targeted crops; (ii) increase in the yield of targeted livestock products (milk, meat and eggs); (iii) increase in proportion of pregnant and nursing mothers and children between 6-24 months’ age adopting appropriate feeding practices The highest project policy-making body, the Project Steering Committee, has been formed and had met seven months ago, involving a representative each of the National Peasant Coalition and the NGO Federation of Nepal. -

1. West Seti Watershed: Nature, Wealth and Power

i Cover photo: A view of the Weti Seti watershed and river from Bajhang Photo credit: USAID Paani Program/Basanta Singh WEST SETI WATERSHED PROFILE WEST SETI WATERSHED PROFILE: STATUS, CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR IMPROVED WATER RESOURCE MANAGEMENT Program Title: USAID Paani Program DAI Project Number: 1002810 Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID/Nepal IDIQ Number: AID-OAA-I-14-00014 Task Order Number: AID-367-TO-16-00001 Contractor: DAI Global LLC Date of Publication: March 26, 2019 The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. ii WEST SETI WATERSHED PROFILE Contents TABLES ........................................................................................................................ V FIGURES .................................................................................................................... VII ABBREVIATIONS ..................................................................................................... IX ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................... 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................ 2 1. WEST SETI WATERSHED: NATURE, WEALTH AND POWER .................... 9 2. NATURE ................................................................................................................. 10 2.1 WEST SETI WATERSHED ............................................................................................. -

Results of a Drinking Water Survey in Bajhang District, Nepal

HEAR Nepal (Health, Education, Awareness and Rights) A Nepalese registered non-profit organization By Madhav Joshi Results of a Drinking Water Survey in Bajhang District, Nepal Introduction/Background Water is one of the basic human necessities and in the Millennium Development Goals, one of the targets is to substantially reduce the proportion of people without access to safe water. A large proportion of the Nepalese population is devoid of access to safe and adequate drinking water. In a country of around 6,000 rivers, the water crisis in Nepal sounds a bit paradoxical. According to the 2011 census, 85 per cent of Nepalis had access to drinking water, up from 72 per cent. This indeed is huge progress compared to 1990 when only 46 per cent of the population had access to drinking water. However, according to the Department of Water Supply and Sewerage in Nepal, although most people have access to drinking water, it is generally not safe. Water is needed for the maintenance of health. Its importance is not only related to the quantity, but also the quality. Access to water in the required quantity is needed to achieve good personal and domestic hygiene practices. Good quality water ensures that ingested water does not constitute a health hazard, even after a lifetime of consumption. It is, however, estimated that the drinking of contaminated water is responsible for 88% of the cases of diarrhoeal diseases that occur in the world every year, and deaths that result from them. It is also indirectly responsible for the 50% of childhood malnutrition that is linked to diarrhoeal and dysentery diseases. -

Annual Report 2074-075

UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION ANNUAL REPORT 2074/75 | 17/18 Sanothimi, Bhaktapur, Nepal Website: http://www.ugcnepal.edu.np UN IV ERSITY E-mail: [email protected] UNIV ERSITY GRANTS Post Box: 10796, Kathmandu, Nepal GRANTS Phone: (977-1) 6638548, 6638549, 6638550 COMMISSION Fax: 977-1-6638552 COMMISSION ANNUAL REPORT 2074/75 17/18 UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION (UGC) Sanothimi, Bhaktapur, Nepal Website: www.ugcnepal.edu.np ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS BPKISH B.P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences CEDA Centre for Economic Development and Administration CERID Research Centre for Educational Innovation and Development CNAS Centre for Nepal and Asian Studies DoE Department of Education GoN Government of Nepal HEMIS Higher Education Management Information System EMIS Education Management Information System HSEB Higher Secondary Education Board IAAS Institute of Agriculture and Animal Sciences IDA International Development Association IoE Institute of Engineering IoF Institute of Forestry IoM Institute of Medicine IoST Institute of Science and Technology J&MC Journalism and Mass Communication KU Kathmandu University LBU Lumbini Buddha University NAMS National Academy of Medical Science NPU Nepal Public University NSU Nepal Sanskrit University PAD Project Appraisal Document PAHS Patan Academy of Health Sciences PokU Pokhara University PRT Peer Review Team PU Purbanchal University QAA Quality Assurance and Accreditation QAAC Quality Assurance and Accreditation Committee RBB Rashtriya Banijya Bank RECAST Research Centre for Applied Science and Technology SFAFD Student Financial Assistance Fund Development SFAFDB Student Financial Assistance Fund Development Board SHEP Second Higher Education Project RMC Research Management Cell SSR Self-Study Report TU Tribhuvan University TUCL TU Central Library UGC University Grants Commission CONTENTS SECTION I: UGC, NEPAL: A BRIEF INTRODUCTION ..................................................... -

Government of Nepal Ministry of Physical Planning and Works Department of Roads

FINAL Government of Nepal Ministry of Physical Planning and Works Department of Roads ROAD SECTOR DEVELOPMENT PROJECT (AF) (IDA GRANT NO: H629 – NEP) (IDA CREDIT NO: 4832 – NEP) (New Project Preparation and Supervision Services) RESETTLEMENT ACTION PLAN KALANGAGAD-CHAINPUR ROAD MMM Group Ltd. (Canada) in JV with SAI Consulting Engineers (P) Ltd. (India) in association with ITECO Nepal (P) Ltd. (Nepal) & Total Management Services (Nepal) February 2011 Resettlement Action Plan February 2011 Kalangagad-Chainpur Road EXECUTIVE SUMMARY PROJECT INTRODUCTION The Government of Nepal (GoN) has given high importance to the expansion of the country's road transportation facility in remote areas. In this context the Ministry of Physical Planning and Works, Department of Roads (DoR) is implementing a number of road projects in Central, Mid-Western and Far-Western regions of the country. Project Background Kalangagad-Chainpur sub-project road which is classed as Feeder Road, starts at Kalangagad of Bajhang district and ends at Chainpur the district headquarters of Bajhang. The road has linked Banjh, Rayel, Bhairabnath, Chaudhari, Matela, Subeda, Rithapata and Chainpur VDCs. The sub-project is upgrading of existing road. For the upgrading works, additional land is required. Road Section Km Design Standard District Kalangagadh Chainpur 47 Single lane otta seal Bajhang Aims of the Resettlement Action Plan The aim for the preparation of this Resettlement Action Plan (RAP) is to provide the policy and procedures of land acquisition, compensation and resettlement of affected persons, with an aim to improve the socio-economic condition of the PAPs in future, providing compensation, resettlement and rehabilitation assistances, consistent with the provisions of the Road Sector Wide Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF). -

Nepal: West Seti Hydroelectric Project

Environmental Assessment Report Summary Environmental Impact Assessment Project Number: 40919 August 2007 Nepal: West Seti Hydroelectric Project Prepared by West Seti Hydro Limited for the Asian Development Bank (ADB). The summary environmental impact assessment is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. CURRENCY (as of 30 June 2007) Currency Unit – Nepalese rupee/s (NRe/NRs) NRe1.00 = $0.0153 $1.00 = NRs65.3 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank EIA – environmental impact assessment EMU – environmental management unit EMAP – environmental management action plan EMP – environmental management plan FSL – full supply level FWDR – Far-Western Development Region GLOF – glacial lake outburst flood HEP – hydroelectric project IUCN – World Conservation Union (formerly International Union for the Conservation of Nature) MOEST – Ministry of Environment, Science and Technology MWDR – Mid-Western Development Region PDB – plant design and build (contractor) PGCIL – Power Grid Corporation of India (Limited) ROW – right-of-way SEIA – summary environmental impact assessment VDC – village development committee WSH – West Seti Hydro Limited WEIGHTS AND MEASURES oC – degrees Celsius GWh – gigawatt-hours ha – hectare km – kilometer kV – kilovolt m – meter m3 – cubic meter m3/s – cubic meter per second MW – megawatt NOTE In this report, “$” refers to US dollars. CONTENTS Page MAPS I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. DESCRIPTION OF THE PROJECT 1 III. DESCRIPTION OF THE ENVIRONMENT 3 A. Physical Resources 3 B. Ecological Resources 4 C. Economic Development 6 D. Social and Cultural Resources 8 IV. ALTERNATIVES 9 A. Without the Project 9 B.