Polynesian Origins: More Word on the Mormon Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Session Slides

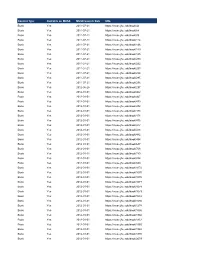

Content Type Available on MUSE MUSE Launch Date URL Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/42 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/68 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/89 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/114 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/146 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/149 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/185 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/280 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/292 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/293 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/294 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/295 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/296 Book Yes 2012-06-26 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/297 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/462 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/467 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/470 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/472 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/473 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/474 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/475 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/477 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/478 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/482 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/494 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/687 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/708 Book Yes 2012-01-11 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/780 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/834 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/840 Book Yes 2012-01-01 -

The Geographies of Maori-Mormonism and the Creation

Western Geography, 15/16 (2005/2006), pp. 108–122 ©Western Division, Canadian Association of Geographers Student Writing The Geographies of Maori–Mormonism and the Creation of a Cross-Cultural Hybrid Matthew Summerskill Geography Program University of Northern British Columbia Prince George, BC V2N 4Z9 This paper explores how the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints attracted a large Maori following in late 19th century New Zealand, and examines key fea- tures of Maori–Mormonism at this time. It focuses on how the alienation of Maori lands during the New Zealand Wars led to Maori resistance of British-based religion. Mormonism attracted Maori because it was non-British, fulfilled Maori prophecies, coincided with some pre-existing Maori values, and provided Maori an inspiring ancestral path. However Maori also resisted attacks that Mormon missionaries launched on aspects of their traditional culture. This paper suggests that newly produced Maori–Mormon (hybrid) spaces were largely shaped by Mormon missionaries’ embracement of ‘acceptable’ Maori culture, and missionary attempts to undercut Maori traditions that conflicted with Latter-day Saint doctrines. Introduction In New Zealand, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has often been called a Maori church (Barber & Gilgen, 1996; Britsch, 1986). Likewise, Latter-day Saints have always prided The Geographies of Maori–Mormonism 109 themselves for their success in attracting Maori to the Mormon Church—particularly where other churches have failed (Lineham, 1991). Why is it that Mormonism has such a strong Maori follow- ing, and when did it gain authenticity among the Maori? For the Mormon mission, was it a case of being in the right place at the right time? Or was it that Mormonism offered more to the Maori way of life than we might expect? This paper examines the means by which Maori were drawn to Mormonism (i.e., land grievances, prophecies, and cultural compatibility), and places a particular emphasis on the concept of hybridity. -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 2, 1999

Journal of Mormon History Volume 25 Issue 2 Article 1 1999 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 2, 1999 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (1999) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 2, 1999," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 25 : Iss. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol25/iss2/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 2, 1999 Table of Contents CONTENTS LETTERS viii ARTICLES • --David Eccles: A Man for His Time Leonard J. Arrington, 1 • --Leonard James Arrington (1917-1999): A Bibliography David J. Whittaker, 11 • --"Remember Me in My Affliction": Louisa Beaman Young and Eliza R. Snow Letters, 1849 Todd Compton, 46 • --"Joseph's Measures": The Continuation of Esoterica by Schismatic Members of the Council of Fifty Matthew S. Moore, 70 • -A LDS International Trio, 1974-97 Kahlile Mehr, 101 VISUAL IMAGES • --Setting the Record Straight Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, 121 ENCOUNTER ESSAY • --What Is Patty Sessions to Me? Donna Toland Smart, 132 REVIEW ESSAY • --A Legacy of the Sesquicentennial: A Selection of Twelve Books Craig S. Smith, 152 REVIEWS 164 --Leonard J. Arrington, Adventures of a Church Historian Paul M. Edwards, 166 --Leonard J. Arrington, Madelyn Cannon Stewart Silver: Poet, Teacher, Homemaker Lavina Fielding Anderson, 169 --Terryl L. -

C.001 C., JE “Dr. Duncan and the Book of Mormon.”

C. C.001 C., J. E. “Dr. Duncan and the Book of Mormon.” MS 52 (1 September 1890): 552-56. A defense of the Book of Mormon against the criticism of Dr. Duncan in the Islington Gazette of August 18th. Dr. Duncan, evidently a literary critic, concluded that the Book of Mormon was either a clumsy or barefaced forgery or a pious fraud. The author writes that the Book of Mormon makes clear many doctrines that are difcult to understand in the Bible. Also, the history and gospel taught by the Bible and the Book of Mormon are similar because both were inspired of God. [B. D.] C.002 C., M. J. “Mormonism.” Plainsville Telegraph (March 3, 1831): 4. Tells of the conversion of Sidney Rigdon who read the Book of Mormon and “partly condemned it” but after two days accepted it as truthful. He asked for a sign though he knew it was wrong and saw the devil appearing as an angel of light. The author of this article warns against the Book of Mormon and against the deception of the Mormons. [J.W.M.] C.003 Cadman, Sadie B., and Sara Cadman Vancik. A Concordance of the Book of Mormon. Monongahela, PA: Church of Jesus Christ, 1986. A complete but not exhaustive concordance, listing words alphabetically. Contains also a historical chronology of the events in the Book of Mormon. [D.W.P.] C.004 Caine, Frederick Augustus. Morumon Kei To Wa Nanzo Ya? Tokyo: Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1909. A two-page tract. English title is “What is the Book of Mormon?” [D.W.P.] C.005 Cake, Lu B. -

Hagoth and the Polynesian Tradition

Hagoth and the Polynesian Tradition Jerry K. Loveland n what amounts to an aside in the story of the Book of Mormon I peoples, there is in the 63rd chapter of Alma a brief reference to a “curious man” named Hagoth. And it came to pass that Hagoth, he being an exceedingly curi- ous man, therefore he went forth and built him an exceedingly large ship, on the borders of the land Bountiful, by the land Desolation, and launched it into the west sea, by the narrow neck which led into the land northward. And behold, there were many of the Nephites who did enter therein and did sail forth with much provisions, and also many women and children; and they took their course northward. And thus ended the thirty and seventh year. And in the thirty and eighth year, this man built other ships. And the first ship did also return, and many more people did enter into it; and they also took much provisions, and set out again to the land northward. And it came to pass that they were never heard of more. And we suppose that they were drowned in the depths of the sea. And it came to pass that one other ship also did sail forth; and whither she went we know not. (Alma 3:5–8) What we have here, is an account of a colonizing movement of men, women, and children who went out in ships presumably into the Pacific Ocean sometime between 53 and 57 b.c. And they were never heard of again. -

Imperial Zions: Mormons, Polygamy, and the Politics of Domesticity in the Nineteenth Century

Imperial Zions: Mormons, Polygamy, and the Politics of Domesticity in the Nineteenth Century By Amanda Lee Hendrix-Komoto A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Susan M. Juster, Co-Chair Associate Professor Damon I. Salesa, Co-Chair Professor Terryl L. Givens Associate Professor Kali A.K. Israel Professor Mary C. Kelley ii To my grandmother Naomi, my mother Linda, my sisters Laura and Jessica, and my daughter Eleanor iii Acknowledgements This is a dissertation about family and the relationships that people form with each other in order to support themselves during difficult times. It seems right, then, to begin by acknowledging the kinship network that has made this dissertation possible. Susan Juster was an extraordinary advisor. She read multiple drafts of the dissertation, provided advice on how to balance motherhood and academia, and, through it all, demonstrated how to be an excellent role model to future scholars. I will always be grateful for her support and mentorship. Likewise, Damon Salesa has been a wonderful co-chair. His comments on a seminar paper led me to my dissertation topic. Because of him, I think more critically about race. In my first years of graduate school, Kali Israel guided me through the politics of being a working-class woman at an elite academic institution. Even though my work took me far afield from her scholarship, she constantly sent me small snippets of information. Through her grace and generosity, Mary Kelley served as a model of what it means to be a female scholar. -

History Through Seer Stones: Mormon Historical Thought 1890-2010

History Through Seer Stones: Mormon Historical Thought 1890-2010 by Stuart A. C. Parker A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto © Copyright by Stuart A. C. Parker 2011 History Through Seer Stones : Mormon Historical Thought 1890-2010 Stuart A. C. Parker Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto 2011 Abstract Since Mark Leone’s landmark 1979 study Roots of Modern Mormonism , a scholarly consensus has emerged that a key element of Mormon distinctiveness stems from one’s subscription to an alternate narrative or experience of history. In the past generation, scholarship on Mormon historical thought has addressed important issues arising from these insights from anthropological and sociological perspectives. These perspectives have joined a rich and venerable controversial literature seeking to “debunk” Mormon narratives, apologetic scholarship asserting their epistemic harmony or superiority, as well as fault-finding scholarship that constructs differences in Mormon historical thinking as a problem that must be solved. The lacuna that this project begins to fill is the lack of scholarship specifically in the field of intellectual history describing the various alternate narratives of the past that have been and are being developed by Mormons, their contents, the methodologies by which they are produced and the theories of historical causation that they entail. This dissertation examines nine chronica (historical narratives -

The Stevens Genealogy

DR. ELVIRA STEVENS BARNEY AT SEVENTY- ONE YEARS OF AGE.. /y./'P- THE STEVENS GENEALOGY EMBRACING BRANCHES OF THE FAMILY DESCENDED FROM Puritan Ancestry, New England Families not Traceable to Puritan Ancestry and Miscellaneous Branches Wherever Found Together with an Extended Account of the Line of Descent from 1650 to the Present Time of the Author DR. ELVIRA STEVENS BARNEY HEAR COUNTY g^NEALOOlCAL SKELTON PUBLISHING CO. S»LT LAKE CITY. UTAH 190T ?.n BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY PROVO, UTAH I LIVE IN HOPE Stevens and Stephens are forms of the Greek zvord Stephanos. The root from which it is derived }nea)is a crozvn. The Stevens arms here reproduced is recorded in the Jlsitations of Gloucester- shire, 1623, and has been continuously in use by English and American members of the family. Original drawings of this coat of arms may be seen in the British Museum. It is shozcn in can'i)igs at Chavenagh House, and on family tombs. The several mottoes adopted by different branches of the family have been but varia- tions of the one here presented: "I live in hope." Table of Contents. PART I. Stcx'cns Paniilics of Puritan Ancestry. SIXTION. PAGE. Introduction i6 I William Stevens, of (iloucester, Mass 21 IT. Ebenezer Steevens, of Killingworth, Conn 24 III. The Cushnian-Stevens l^'amilies. of New KnglanU 39 IV. The Hapgood-Stevens Families, of Marll)oro, Mass.. 4^ V. Henry Stevens, of Stonington, Conn 45 VI. Thomas Stevens, of Boston, Mass 49 VII. Thomas vStevens, of East Haven, Conn 50 \TII. The Pierce-Stevens Familv. -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 34, No. 1, 2008

Journal of Mormon History Volume 34 Issue 1 Winter 2008 Article 1 2008 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 34, No. 1, 2008 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (2008) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 34, No. 1, 2008," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 34 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol34/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 34, No. 1, 2008 Table of Contents LETTERS --Another Utah War Victim Polly Aird, vi ARTICLES --Restoring, Preserving, and Maintaining the Kirtland Temple: 1880–1920 Barbara B. Walden and Margaret Rastle, 1 --The Translator and the Ghostwriter: Joseph Smith and W. W. Phelps Samuel Brown, 26 --Horace Ephraim Roberts: Pioneering Pottery in Nauvoo and Provo Nancy J. Andersen, 63 --The Mormon Espionage Scare and Its Coverage in Finland, 1982–84 Kim B. Östman, 82 --The Use of “Lamanite” in Official LDS Discourse John-Charles Duffy, 118 --Yesharah: Society for LDS Sister Missionaries Kylie Nielson Turley, 168 --Backcountry Missionaries in the Post-Bellum South: Thomas Ephraim Harper’s Experience Reid L. Harper, 204 --“The Assault of Laughter”: The Comic Attack on Mormon Polygamy in Popular Literature Richard H. Cracroft, 233 REVIEWS --Lowell C. Bennion, Alan T. Morrell, and Thomas Carter. Polygamy in Lorenzo Snow’s Brigham City: An Architectural Tour Alan Barnett, 263 --Reid L. -

The Faith Healer's Pledge: How Early Mormons Captured Audiences

The Faith Healer’s Pledge: How early Mormons Captured Audiences Tal Meretz (Monash University) Abstract: This paper explores the use of faith healing in attracting converts to early Mormonism, by investigating the diaries and autobiographies of both converts and missionaries. It argues that while faith healing was technically banned from being used to convert people, it still played a specific but essential role as a ‘clincher’ for those on the brink of conversion. It explores faith healing in relation to the Mormon conversion process as a whole, and resolves the theologically inconsistent position on magic and supernaturalism. It contends that the use of faith healing in the Mormon missionary process has gone largely unacknowledged because previous scholars have prioritised official Mormon documents over unofficial personal writings. Key Words: Mormon, Joseph Smith, faith healing, conversion, nineteenth century America, missionaries, diaries, autobiographies, life writings. INTRODUCTION In 1831, Gilbert Belnap travelled to Kirtland, Ohio. He had heard that a third temple was being built there by the Mormons and wanted to see it for himself.1 In his autobiography, Gilbert wrote of the temple, “the architecture and the construction of the interior of this temple of worship surely must have been of ancient origin as the master builder has said that the plan thereof was given by revelation from God, and I see no reason why this should not be credited for no one can disprove it.”2 He was enamoured I would like to thank my two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. 1 While the Church would undergo several name changes before being named Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, this paper will use the informal term for members of the Church – Mormons - and will refer to their religion as Mormonism. -

Mormons and Icarians in Nauvoo, Illinois

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2009 Utopian spaces: Mormons and Icarians in Nauvoo, Illinois Sarah Jaggi Lee College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, Geography Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Lee, Sarah Jaggi, "Utopian spaces: Mormons and Icarians in Nauvoo, Illinois" (2009). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623544. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-2x4q-vh31 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Utopian Spaces: Mormons and lcarians in Nauvoo, Illinois Sarah Jaggi Lee Logan, Utah Master of Arts, The College of William & Mary, 2004 Bachelor of Arts, Brigham Young University, 2001 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies Program The College of William and Mary May 2009 APPROVAL PAGE This Dissertatiqn is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ;?~. App h 2009 Committee C ir Associate Profe sor Maureen A. Fi erald, American Studies \ The College of W~li m & Mary u' - J ~lure and Religion University of Richmond ABSTRACT PAGE Nauvoo, Illinois was the setting for two important social experiments in the middle of the nineteenth century. -

Glory Enough

CHAPTER 2 Glory Enough Editors’ note: This is an excerpt of chapter 2 from No Unhallowed Hand, volume 2 in the Saints series. (Volume 2 will be released early next year.) The previous chapter, in the July issue, describes the advance company of migrating Saints, called the “Camp of Israel.” They have been camped at Sugar Creek, a relatively short distance across the Mississippi River from Nauvoo. On March 1, 1846, Brigham Young began to lead the advance company west. hile the Saints with Brigham Young were leaving Sugar Creek, 43-year- old Louisa Pratt remained in Nauvoo, preparing to leave the city with her four young daughters. Three years earlier, the Lord had called her hus- Wband, Addison, on a mission to the Pacific Islands. Since then, unreliable mail service between Nauvoo and Tubuai, the island in French Polynesia where Addison was serving, had made it hard to stay in contact with him. Most of his letters were several months old when they arrived, and some were older than a year. Addison’s latest letter made it clear that he would not be home in time to go west with her. The Twelve had instructed him to remain in the Pacific Islands until they called him home or sent missionaries to replace him. At one point, Brigham had hoped to send more missionaries to the islands after the Saints received the endowment, but the exodus from Nauvoo had postponed that plan.1 Louisa was willing to make the journey without her husband, but thinking about it made her nervous.