19. Radiation and Optics in the Atmosphere and 19.3 Aerosols and Clouds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Atmospheric Radiation Model for Cerro Paranal

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. nolletal2012a c ESO 2012 May 10, 2012 An atmospheric radiation model for Cerro Paranal I. The optical spectral range⋆ S. Noll1, W. Kausch1, M. Barden1, A. M. Jones1, C. Szyszka1, S. Kimeswenger1, and J. Vinther2 1 Institut f¨ur Astro- und Teilchenphysik, Universit¨at Innsbruck, Technikerstr. 25/8, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria e-mail: [email protected] 2 European Southern Observatory, Karl-Schwarzschild-Str. 2, 85748 Garching, Germany Received; accepted ABSTRACT Aims. The Earth’s atmosphere affects ground-based astronomical observations. Scattering, absorption, and radiation processes dete- riorate the signal-to-noise ratio of the data received. For scheduling astronomical observations it is, therefore, important to accurately estimate the wavelength-dependent effect of the Earth’s atmosphere on the observed flux. Methods. In order to increase the accuracy of the exposure time calculator of the European Southern Observatory’s (ESO) Very Large Telescope (VLT) at Cerro Paranal, an atmospheric model was developed as part of the Austrian ESO In-Kind contribution. It includes all relevant components, such as scattered moonlight, scattered starlight, zodiacal light, atmospheric thermal radiation and absorption, and non-thermal airglow emission. This paper focuses on atmospheric scattering processes that mostly affect the blue (< 0.55 µm) wavelength regime, and airglow emission lines and continuum that dominate the red (> 0.55 µm) wavelength regime. While the former is mainly investigated by means of radiative transfer models, the intensity and variability of the latter is studied with a sample of 1186 VLT FORS 1 spectra. Results. For a set of parameters such as the object altitude angle, Moon-object angular distance, ecliptic latitude, bimonthly period, and solar radio flux, our model predicts atmospheric radiation and transmission at a requested resolution. -

![Arxiv:1710.01658V1 [Physics.Optics] 4 Oct 2017 to Ask the Question “What Is the RI of the Small Parti- Cles Contained in the Inhomogeneous Sample?”](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4841/arxiv-1710-01658v1-physics-optics-4-oct-2017-to-ask-the-question-what-is-the-ri-of-the-small-parti-cles-contained-in-the-inhomogeneous-sample-24841.webp)

Arxiv:1710.01658V1 [Physics.Optics] 4 Oct 2017 to Ask the Question “What Is the RI of the Small Parti- Cles Contained in the Inhomogeneous Sample?”

Extinction spectra of suspensions of microspheres: Determination of spectral refractive index and particle size distribution with nanometer accuracy Jonas Gienger,∗ Markus Bär, and Jörg Neukammer Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (PTB), Abbestraße 2–12, 10587 Berlin, Germany (Dated: Compiled October 5, 2017) A method is presented to infer simultaneously the wavelength-dependent real refractive index (RI) of the material of microspheres and their size distribution from extinction measurements of particle suspensions. To derive the averaged spectral optical extinction cross section of the microspheres from such ensemble measurements, we determined the particle concentration by flow cytometry to an accuracy of typically 2% and adjusted the particle concentration to ensure that perturbations due to multiple scattering are negligible. For analysis of the extinction spectra we employ Mie theory, a series-expansion representation of the refractive index and nonlinear numerical optimization. In contrast to other approaches, our method offers the advantage to simultaneously determine size, size distribution and spectral refractive index of ensembles of microparticles including uncertainty estimation. I. INTRODUCTION can be inferred from measurements of the scattering and absorption of light by the particles. The refractive index (RI) describes the refraction of a A reference case is that of homogeneous spheres de- beam of light at a (macroscopic) interface between any scribed by a single refractive index, since an analytical two materials. Consequently, a variety of experimental solution for the mathematical problem of light scatter- methods exist for measuring the RI of a material that rely ing exists for this class of particles (Mie theory) [12, 13]. on the refraction or reflection of light at a planar interface This makes the analysis of light scattering data feasible between the sample and some other known material, such and at the same time is a good approximation for many as air, water or an optical glass. -

Using Temperature As the Basis, the Atmosphere Is Divided Into Four Layers

Using temperature as the basis, the atmosphere is divided into four layers. The temperature decrease in the troposphere, the bottom layer in which we live, is called the "environmental lapse rate." Its average value is 6.5°C per kilometer, a figure known as the "normal lapse rate." A temperature "inversion," in which temperatures increase with height, is sometimes observed in shallow layers in the troposphere. The thickness of the troposphere is generally greater in the tropics than in polar regions. Essentially all important weather phenomena occur in the troposphere. Beyond the troposphere lies the stratosphere; the boundary between the troposphere and stratosphere is known as the tropopause. In the stratosphere, the temperature at first remains constant to a height of about 20 kilometers (12 miles) before it begins a sharp increase due to the absorption of ultraviolet radiation from the Sun by ozone. The temperatures continue to increase until the stratopause is encountered at a height of about 50 kilometers (30 miles).In the mesosphere, the third layer, temperatures again decrease with height until the mesopause, some 80 kilometers (50 miles) above the surface.The fourth layer, the thermosphere, with no well-defined upper limit, consists of extremely rarefied air. Temperatures here increase with an increase in altitude.Besides layers defined by vertical variations in temperature, the atmosphere is often divided into two layers based on composition. The homosphere (zone of homogeneous composition), from Earth’s surface to an altitude of about 80 kilometers (50 miles), consists of air that is uniform in terms of the proportions of its component gases. -

Background Stratospheric Aerosol Investigations Using Multi-Color Wide-Field Measurements of the Twilight Sky

Background Stratospheric Aerosol Investigations Using Multi-Color Wide-Field Measurements of the Twilight Sky Oleg S. Ugolnikov and Igor A. Maslov Space Research Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences Profsoyuznaya st., 84/32, Moscow 117997 Russia E-mail: [email protected] First results of multi-wavelength measurements of the twilight sky background using all-sky camera with RGB-color CCD conducted in spring and summer of 2016 in central Russia (55.2°N, 37.5°E) are discussed. They show the effect of aerosol scattering at altitudes up to 35 km which significantly increases to the long-wave range (624 nm, R channel). Analysis of sky color behavior during the light period of twilight with account of ozone Chappuis absorption allows retrieving the angle dependencies of scattering on the stratospheric aerosol particles. This is used to find the parameters of lognormal size distribution: median radius about 0.08 microns and width 1.5-1.6 for stratospheric altitude range. 1. Introduction It is well-known that most part of aerosol particles in the atmosphere of Earth is distributed in its lower layer, the troposphere. However, upper atmospheric layers are not absolutely free from solid or liquid particles. As early as in late XIX century, after Krakatoa eruption in 1883, the color change of the twilight sky was noticed (Clark, 1883), the phenomenon was called "volcanic purple light" (Lee and Hernádez-Andrés, 2003). Gruner and Kleinert (1927) explained it by aerosol light scattering above the troposphere. Existence of aerosol layer in the lower stratosphere was confirmed in balloon experiments (Junge et al, 1961), and it was called Junge layer. -

12 Light Scattering AQ1

12 Light Scattering AQ1 Lev T. Perelman CONTENTS 12.1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 321 12.2 Basic Principles of Light Scattering ....................................................................................323 12.3 Light Scattering Spectroscopy ............................................................................................325 12.4 Early Cancer Detection with Light Scattering Spectroscopy .............................................326 12.5 Confocal Light Absorption and Scattering Spectroscopic Microscopy ............................. 329 12.6 Light Scattering Spectroscopy of Single Nanoparticles ..................................................... 333 12.7 Conclusions ......................................................................................................................... 335 Acknowledgment ........................................................................................................................... 335 References ...................................................................................................................................... 335 12.1 INTRODUCTION Light scattering in biological tissues originates from the tissue inhomogeneities such as cellular organelles, extracellular matrix, blood vessels, etc. This often translates into unique angular, polari- zation, and spectroscopic features of scattered light emerging from tissue and therefore information about tissue -

How the Sun Paints the Sky the Generation of Its Colour and Luminosity Bob Fosbury European Southern Observatory and University College London

How the Sun Paints the Sky The generation of its colour and luminosity Bob Fosbury European Southern Observatory and University College London Introduction: the 19th century context — science and painting The appearance of a brilliantly clear night sky must surely have stimulated the curiosity of our earliest ancestors and provided them with the foundation upon which their descendants built the entire edifice of science. This is a conclusion that would be dramatically affirmed if any one of us were to look upwards in clear weather from a location that is not polluted by artificial light: an increasingly rare possibility now, but one that provides a welcome regeneration of the sense of wonder. What happened when our ancient ancestors gazed instead at the sky in daylight or twilight? It is difficult to gauge from written evidence as there was such variation in the language of description among different cultures (see “Sky in a bottle” by Peter Pesic. MIT Press, 2005. ISBN 0-262-16234-2). The blue colour of a cloudless sky was described in a remarkable variety of language, but the question of its cause most often remained in the realm of a superior being. Its nature did concern the Greek philosophers but they appeared to describe surfaces and objects in the language of texture rather than colour: they did not have a word for blue. It was only during the last millennium that thinkers really tried to get to grips with the problem, with Leonardo da Vinci, Isaac Newton and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe all applying themselves. It was not easy however, and no real progress was made until the mid-19th century when there was a focus of the greatest scientific minds of the time on the problem of both the colour and the what was then the novel property of polarisation of the light. -

Colorimetric Analysis of Outdoor Illumination Across Varieties of Atmospheric Conditions

Research Article Vol. 33, No. 6 / June 2016 / Journal of the Optical Society of America A 1049 Colorimetric analysis of outdoor illumination across varieties of atmospheric conditions 1, 2 3 2 2 SHAHRAM PEYVANDI, *JAVIER HERNÁNDEZ-ANDRÉS, F. J. OLMO, JUAN LUIS NIEVES, AND JAVIER ROMERO 1Department of Psychology, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Newark, New Jersey 07102, USA 2Department of Optics, Sciences Faculty, University of Granada, Granada 18071, Spain 3Department of Applied Physics, Sciences Faculty, University of Granada, Granada 18071, Spain *Corresponding author: [email protected] Received 8 February 2016; revised 9 April 2016; accepted 10 April 2016; posted 11 April 2016 (Doc. ID 259168); published 10 May 2016 Solar illumination at ground level is subject to a good deal of change in spectral and colorimetric properties. With an aim of understanding the influence of atmospheric components and phases of daylight on colorimetric specifications of downward radiation, more than 5,600,000 spectral irradiance functions of daylight, sunlight, and skylight were simulated by the radiative transfer code, SBDART [Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 79, 2101 (1998)], under the atmospheric conditions of clear sky without aerosol particles, clear sky with aerosol particles, and overcast sky. The interquartile range of the correlated color temperatures (CCT) for daylight indicated values from 5712 to 7757 K among the three atmospheric conditions. A minimum CCT of ∼3600 K was found for daylight when aerosol particles are present in the atmosphere. Our analysis indicated that hemispheric day- light with CCT less than 3600 K may be observed in rare conditions in which the level of aerosol is high in the atmosphere. -

![Arxiv:2008.11688V1 [Astro-Ph.CO] 26 Aug 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0465/arxiv-2008-11688v1-astro-ph-co-26-aug-2020-410465.webp)

Arxiv:2008.11688V1 [Astro-Ph.CO] 26 Aug 2020

APS/123-QED Cosmology with Rayleigh Scattering of the Cosmic Microwave Background Benjamin Beringue,1 P. Daniel Meerburg,2 Joel Meyers,3 and Nicholas Battaglia4 1DAMTP, Centre for Mathematical Sciences, Wilberforce Road, Cambridge, UK, CB3 0WA 2Van Swinderen Institute for Particle Physics and Gravity, University of Groningen, Nijenborgh 4, 9747 AG Groningen, The Netherlands 3Department of Physics, Southern Methodist University, 3215 Daniel Ave, Dallas, Texas 75275, USA 4Department of Astronomy, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, USA (Dated: August 27, 2020) The cosmic microwave background (CMB) has been a treasure trove for cosmology. Over the next decade, current and planned CMB experiments are expected to exhaust nearly all primary CMB information. To further constrain cosmological models, there is a great benefit to measuring signals beyond the primary modes. Rayleigh scattering of the CMB is one source of additional cosmological information. It is caused by the additional scattering of CMB photons by neutral species formed during recombination and exhibits a strong and unique frequency scaling ( ν4). We will show that with sufficient sensitivity across frequency channels, the Rayleigh scattering/ signal should not only be detectable but can significantly improve constraining power for cosmological parameters, with limited or no additional modifications to planned experiments. We will provide heuristic explanations for why certain cosmological parameters benefit from measurement of the Rayleigh scattering signal, and confirm these intuitions using the Fisher formalism. In particular, observation of Rayleigh scattering P allows significant improvements on measurements of Neff and mν . PACS numbers: Valid PACS appear here I. INTRODUCTION direction of propagation of the (primary) CMB photons. There are various distinguishable ways that cosmic In the current era of precision cosmology, the Cosmic structures can alter the properties of CMB photons [10]. -

Apihelion Vs

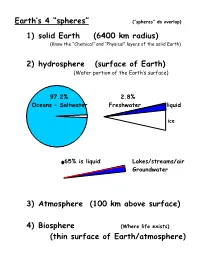

Earth’s 4 “spheres” (“spheres” do overlap) 1) solid Earth (6400 km radius) (Know the “Chemical” and “Physical” layers of the solid Earth) 2) hydrosphere (surface of Earth) (Water portion of the Earth’s surface) 97.2% 2.8% Oceans – Saltwater Freshwater liquid ice .65% is liquid Lakes/streams/air Groundwater 3) Atmosphere (100 km above surface) 4) Biosphere (Where life exists) (thin surface of Earth/atmosphere) Weather vs Climate constantly “average weather” changing 6 basic elements of weather/climate temperature of air humidity of air type & amount of cloudiness type & amount of precipitation pressure exerted by air speed & direction of wind Atmosphere Composition / Ozone Layer (pgs. 6-9) Evolution of Earth’s Atmosphere (pgs. 9-11) Exploring the Atmosphere time line for inventions/discoveries 1593 Galileo “thermometer” 1643 Torricelli barometer 1661 Boyle (P)(V)=constant 1752 Franklin kite -> lightning=electricity 1880(90) manned ballons 1900-today unmanned ballons using radiosondes = radio transmitters that send info on temperature/pressure/relative humidity today rockets & airplanes weather radar & satellites Height/Structure of Atmosphere Exosphere (above 800 km) 100 km 100 km (Ionosphere) 90 km Thermosphere 90 km 80 km 80 km 70 km 70 km 60 km Mesosphere 60 km 50 km 50 km 40 km (Ozone Layer) 40 km 30 km Stratosphere 30 km 20 km 20 km 10 km 10 km Troposphere 0 km 0 km extremely 0o hot really hot 0 100 500 1000 cold Temperature Pressure (mb) Homosphere vs Heterosphere 0-80 km above 80 km uniform distribution varies by mass of molecule N2 O He H Ionosphere located in the Thermosphere/Heterosphere N2 O ionize due to absorbing high-energy solar energy lose electrons and become +charged ions electrons are free to move Solar flares let go of lots of solar energy (charged particles) The charged particles mix with Earth’s magnetic field Charged particles are guided toward N-S magnetic poles Charged particles mix with ionosphere and cause Auroras Electromagnetic Spectrum Seasons are due to angle of sun’s rays. -

Atmospheric Gases and Air Quality

12.3SECTION Atmospheric Gases and Air Quality Key Terms + Exosphere H H criteria air contaminants 500 He- He Ionosphere O Thermosphere 1 1 1 O 1NO 1OZ 1 2 1 1 Heterosphere NZ 1O 90 Photoionization N2 O2 10-5 70 Mesosphere CO 2 Pressure (mmHg) Pressure -3 of O Photodissociation Figure 12.10 Variations in 10 50 (km)Altitude 78% N2 pressure, temperature, and 21% O CO2 O2 Stratosphere 2 the components that make 1% Ar. etc. Ozone layer up Earth’s atmosphere are 30 Homosphere summarized here. 10-1 Infer How can you explain the changes in temperature Troposphere 10 of O Photodissociation H2O with altitude? 1 150 273 300 2000 major major major components components components Temperature (˚C) Figure 12.10 summarizes information about the structure and composition of Earth’s atmosphere. Much of this information is familiar to you from earlier in this unit or from your study of science or geography in earlier grades. As you know from Boyle’s law, gases are compressible. Th us, pressure in the atmosphere decreases with altitude, and this decrease is more rapid at lower altitudes than at higher altitudes. In fact, the vast majority of the mass of the atmosphere—about 99 percent—lies within 30 km of Earth’s surface. About 90 percent of the mass of the atmosphere lies within 15 km of the surface, and about 75 percent lies within 11 km. Th e atmosphere is divided into fi ve distinct regions, based on temperature changes. You may recognize the names of some or perhaps all of these regions: the troposphere, stratosphere, mesosphere, thermosphere, and exosphere. -

Rayleigh Scattering by Gas Molecules: Why Is the Sky Blue?

Please do not remove this manual from from the lab. It is available via Canvas DEMO NOTES: This manual contains demonstrator notes in blue italics Optics Rayleigh Scattering: 12 hrs Rayleigh scattering by gas molecules: why is the sky blue? Objectives After completing this experiment: • You will be familiar with using a photomultiplier tube) as a means of measuring low intensities of light; • You will have had experience of working safely with a medium power laser producing visible wavelength radiation; • You will have had an opportunity to use the concept of solid angle in connection with scattering experiments; • You will have had the opportunity to experimentally examine the phenomenon of polarization; • You should understand how the scattering of light from molecules varies accord- ing to the direction of polarization of the light and the scattering angle relative to it; • You should have a good understanding of what is meant by cross-section and differential cross section. • You should be able to describe why the daytime sky appears to be blue and why light from the sky is polarized. Note the total time for data-taking in this experiment is about one hour. There are a lot of useful physics concepts to absorb in the background material. You should read the manual bearing in mind that you need to thoroughly understand how you will calculate your results from you measurements BEFORE your final lab session. This is an exercise in time management. Safety A medium power Argon ion laser is used in this experiment. The light from it is potentially dangerous to you and other people in the room. -

Elemental Geosystems, 5E (Christopherson) Chapter 2 Solar Energy, Seasons, and the Atmosphere

Elemental Geosystems, 5e (Christopherson) Chapter 2 Solar Energy, Seasons, and the Atmosphere 1) Our planet and our lives are powered by A) energy derived from inside Earth. B) radiant energy from the Sun. C) utilities and oil companies. D) shorter wavelengths of gamma rays, X-rays, and ultraviolet. Answer: B 2) Which of the following is true? A) The Sun is the largest star in the Milky Way Galaxy. B) The Milky Way is part of our Solar System. C) The Sun produces energy through fusion processes. D) The Sun is also a planet. Answer: C 3) Which of the following is true about the Milky Way galaxy in which we live? A) It is a spiral-shaped galaxy. B) It is one of millions of galaxies in the universe. C) It contains approximately 400 billion stars. D) All of the above are true. E) Only A and B are true. Answer: D 4) The planetesimal hypothesis pertains to the formation of the A) universe. B) galaxy. C) planets. D) ocean basins. Answer: C 5) The flattened structure of the Milky Way is revealed by A) the constellations of the Zodiac. B) a narrow band of hazy light that stretches across the night sky. C) the alignment of the planets in the solar system. D) the plane of the ecliptic. Answer: B 6) Earth and the Sun formed specifically from A) the galaxy. B) unknown origins. C) a nebula of dust and gases. D) other planets. Answer: C 7) Which of the following is not true of stars? A) They form in great clouds of gas and dust known as nebula.