Breaking Through the Develop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ENLISTMENT CATEGORY LICENSE NO ADDRESS COMPANY NAME ENLISTMENT TYPE OWNER NAME SECTION Trading-Jewellery Showroom 20004117034 5

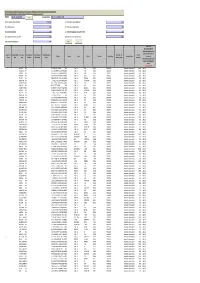

ENLISTMENT ENLISTMENT COMPANY OWNER NAME SECTION CATEGORY LICENSE NO ADDRESS NAME TYPE Satya Kinkar Trading-Jewellery 59,Deshpriya Nagar Colony- Shantiniketan Individual 118 Showroom 20004117034 23 Jewellery House Manna Trading-Stationery & Individual Sarala Majhi 118 Grocery 2000414536 44/R/3,Rabindra Nagar-14 Sarala Majhi Service-Punching Of Card Individual Nirmal Dubey 201 Board Box 20004119384 9,Surjya Sen Road-8 Dubey Punching Ajay Kumar Trading-Auto Sale & Muskan Individual 118 Purchase 2000414964 199,B.T. Road-2 Enterprise Singh Office-Office For Used Individual Neelam Singh 118 Vehicles Sale & Purchase 20004118647 199,B.T. Road-2 Singh Enterprise Debabrata Office-Office For Civil Maa Manasa Individual 118 Contractor & Developer 20004118454 39,J.Basak Road-26 Enterprise Kundu Pijush Kanti Individual 118 Trading-Stationery Goods 20004115297 245/1,B.T. Road-27 Tuki Taki Gautam Trading-Imitation Goods Loknath City Individual Avijit Basak 118 Shop - Large 20004117481 1,Deshbandhu Road(W)-7 Gold Service-Wholeseller Of Kamala Medical Individual Sayani Samanta 118 Medicine 20004118148 19/5,Neogipara Road-11 Stores Trading-Retail Medicine Kamala Medical Individual Sourav Samanta 118 Shop 2000416040 81,Neogipara Road-11 Hall Smt. Sharmila Trading-Retail Medicine Partnership Dey & Sumit Kr. 118 Shop 2000416416 204,Ashokegarh-2 Deys Medical Dey Trading-Electrical Goods Sudarshan Individual Sudarshan Adak 118 Shop 2000415970 69/33,Baruipara Lane-9 Electric Manufacturing Cum Prasanta Individual 201 Service-Printing Press & 18,Rai M.N.Chowdhury -

Unclaimed Dividend 2009-10 Transferred to IEPF

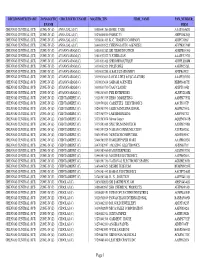

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the amount credited to Investor Education and Protection Fund. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-1 CIN/BCIN L65110TN1916PLC001295 Prefill Company/Bank Name THE KARUR VYSYA BANK LIMITED Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 2131875.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Date of event (date of declaration of dividend/redemption date of preference shares/date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type maturity of Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred bonds/debentures/application money refundable/interest thereon (DD-MON-YYYY) ANASUYAKR NA 25 RAJAJI STREET KARUR INDIA TAMIL NADU KARUR 639001 FOLIOA00054 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend3600.00 21-Jul-2010 ANBUSUBBIAHR NA 4 GANDHI NAGAR IST CROSS KARUR INDIA TAMIL NADU KARUR 639001 FOLIOA00057 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend1152.00 21-Jul-2010 ARJUNABAI NA 68 BAZAAR STREET KEMPANAICKENPALAYAMINDIA VIA D G PUDURTAMIL ERODE NADU R M S ERODE 638503 FOLIOA00122 Amount -

INVALID PAN Listason 23022017 Aligned.Xlsx

DIVISIONOFFICENAME ZONALOFFIC CIRCLEOFFICENAME MASTER_TIN FIRM_NAME PAN_NUMBER_ ENAME FIRM CHENNAI CENTRAL (JCT) ZONE-IV (Z) ANNA SALAI (C) 33080641266 HOME CARE AAAPA8462G CHENNAI CENTRAL (JCT) ZONE-IV (Z) ANNA SALAI (C) 33230600880 FABRIC 33 AHPPG5426Q CHENNAI CENTRAL (JCT) ZONE-IV (Z) ANNA SALAI (C) 33360641403 K. C. TRADING COMPANY ADJPC7696J CHENNAI CENTRAL (JCT) ZONE-IV (Z) ANNA SALAI (C) 33440600522 CHENNAI AUTO AGENCIES AFYPK9579H CHENNAI CENTRAL (JCT) ZONE-IV (Z) AYANAVARAM (C) 33031002182 SRI NIDHI INFOTECH AEMPR0514G CHENNAI CENTRAL (JCT) ZONE-IV (Z) AYANAVARAM (C) 33041002322 N.ETHIRAJAN AAAPE3757G CHENNAI CENTRAL (JCT) ZONE-IV (Z) AYANAVARAM (C) 33111003108 SHIDDHI BOUTIQUE ADHPL8808M CHENNAI CENTRAL (JCT) ZONE-IV (Z) AYANAVARAM (C) 33131002321 P.R.STORES AAKPB2526L CHENNAI CENTRAL (JCT) ZONE-IV (Z) AYANAVARAM (C) 33191002288 G.BALU STATIONERY AFZPB4552J CHENNAI CENTRAL (JCT) ZONE-IV (Z) AYANAVARAM (C) 33191003646 LOYAL LIFTS & ESCALATORS AAAPU6513G CHENNAI CENTRAL (JCT) ZONE-IV (Z) AYANAVARAM (C) 33301003634 SAIRAM AGENCIES BKBPS6887H CHENNAI CENTRAL (JCT) ZONE-IV (Z) AYANAVARAM (C) 33391003730 TAAJ CLASSIC ADIPT3334R CHENNAI CENTRAL (JCT) ZONE-IV (Z) AYANAVARAM (C) 33586363603 PYK ENTRPRISES ALNPY2180M CHENNAI CENTRAL (JCT) ZONE-IV (Z) CHINTADRIPET (C) 33120583335 HERO MARKETING AADPK7753K CHENNAI CENTRAL (JCT) ZONE-IV (Z) CHINTADRIPET (C) 33190580241 CASSETTES ELECTRONICS AACPJ6337P CHENNAI CENTRAL (JCT) ZONE-IV (Z) CHINTADRIPET (C) 33260583743 JAISICA INTERNATIONAL AGPPK7500E CHENNAI CENTRAL (JCT) ZONE-IV (Z) CHINTADRIPET -

Tration Pan First Name Middle Name Last Name

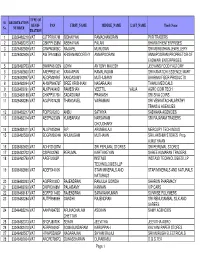

TYPE OF Sl. REGISTRATION REGIS- PAN FIRST_NAME MIDDLE_NAME LAST_NAME Trade Name No. NUMBER TRATION 1 33026482218 VAT CJTPR7977M SIDHAIYAN RAMACHANDRAN PVR TRADERS 2 33026482315 VAT CBKPP1358M ABBHAYAN PALANI BHARATH ENTERPRISES 3 33026482509 VAT CIWPM3458C RAJAVEL MURUGAN SRI MURUGHAN JEWELLERY 4 33026482606 VAT AWTPA1885G KRISHNAMOORTHY ANNAPOORANI ANNAPOORANI PROPRIETOR OF EASWARI ENTERPRISES 5 33026482703 VAT BWRPA6135N JOHN ANTONY MALESH JEEVANS FOOD FACTORY 6 33026482800 VAT AAEPR5314E KANNAPAN RAMALINGAM SRI KAMATCHI ESSENCE MART 7 33026482897 VAT AEQPM3976F KANDASAMY MUTHUSAMY BHARANI FIBER PRODUCTS 8 33026482994 VAT AHWPN6972F SREE KRISHNAN NAGARAJAN THANU MEDICALS 9 33026483091 VAT ALKPV4049D RAMESHAN VEETTIL VALIA AGRO COIR TECH 10 33026483188 VAT CHXPP3176N SADASIVAM PRAKASH SRI SIVA COIRS 11 33026483285 VAT AGJPV0742M THANGAVEL VAIRAMANI SRI VENKATACHALAPATHY TRANS & AGENCIES 12 33036482217 VAT FQIPS9720Q ANBU SATHIYA SADHANA AGENCIES 13 33036482314 VAT AESPN2336N KUMBARAM NARSARAM SRI RAJARAM TRADERS CHOUDHARY 14 33036482411 VAT ALUPA2529H R.P. ARUNBALAJI MERCURY TECH INDUS 15 33036482508 VAT BDGPM3924H ARUMUGAM MUTHAIAN SRI LAKSHMI STORES Prop. A.MUTHAIAN 16 33036482605 VAT ADHFS1087M SRI PERUMAL STORES SRI PERUMAL STORES 17 33036482702 VAT CSIPK4279B PERUMAL KARTHIKEYAN SHREE KUMARAN TRADERS 18 33036482799 VAT AAGFI2063P INSTA3D INSTA3D TECHNOLOGIES LLP TECHNOLOGIES LLP 19 33036482896 VAT ADEFS4416K STAR MINERALS AND STAR MINERALS AND NATURALS NATURALS 20 33036482993 VAT AGIPR9189D RAJENDRAN RANJULA GOWDA SHARON PHARMACY -

Special Survey Report on Port Blair, Series-24

+rR<t qil \J1~4IUI~1 1981 CENSUS OF I~DIA 1981 ~- 24 SERIES - 24 'tfrt CSiACI( 1R Rtilq ~ R41! SPECIAL SURVEY REPORT ON PORT BLAIR atri'4f111 am- f.titl)ill( ~ wm ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS The cover photograph is of notorious and dreaded Cellular Jail-popularly known as the Jail of Kalapani. The construction of the Jail was completed in 1906 which had 698 cells. It is mute sagaman of history of great freedom fighters. The Jail has been declared as National Monument on 11 th Febru~ry, 1979 by Hon'ble Shri Morarji Desai, the then Prime Minister of India. CONTENTS PAGES FOREWORD IX PREFACE XI CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION 1-8 Location and Site Selection, Topography and Physical Environ ment, Flora and Fauna, Climate, Rainfall and Humidity, Transport and Communication, Morphology, Ethnic groups CHAPTER" HISTORY OF GROWTH 9-14 Brief History of the Andamans prior to settlement, First Settlement (1789-1796), second penal settlement; shifting of Headquarters of settlement, Japanese occupation, Groth of Port Blair after Independence, Formation of Port Blair town, Effect of Migration, Impact of Topography on the growth of Population, Wards and residential pattern CHAPTER'" AMENITIES AND SERVICES 15-26 History of~rowth and pres8ilt poSition, Administration, District Office, Police Office, Judiciafjf, A.P.W. D., Forest Department, Electricity, Education, Health, All India ~adio and Doordarshan, Shipping arw .Marine, Port Blair Municipal Board v CHAPTER IV ECONOMIC LIFE OF THE TOWN 27-34 Collection of data, Economic Life, Andaman Chamber of Com merce -

Transfered to IEPF

SATHAVAHANA ISPAT LIMITED UNPAID DIVIDEND DATA FOR THE YEAR 2009-10 Dividend SLNO FOLIONO NAME OF THE SHARE HOLDER SHARE HOLDER ADDRESS PIN No. of Shares Amount (in Rs.) 1 19204 A ANUSOOYA H NO 7 NORTH CAR STREET RAMESWARAM RAMNAD DIST RAMESWARAM 623526 100 150.00 2 IN30051310356402 A ARUNA 17 71/1 RAJA MEDICALS B KOTHAKOTA POST CHITTOOR DIST 517370 200 300.00 3 IN30102221302854 A B R K VARA PRASAD D NO 1 141 DWAJASTAMBAM STREET PALANGI POST UNDRAJAVARAM MANDAL 534216 20 30.00 4 32168 A B S MANIAM 25, VEERASAMY STREET GROUND FLOOR PURASAWALKAM CHENNAI 600007 100 150.00 5 IN30286310222329 A BHUPATHI RAO 39-84/85 BANDAR NAGAR WANAPARTHY MAHABOOB NAGAR 509103 500 750.00 6 6153 A C CHANDY 4/604 TULSI DHAM MAJIWADA PO THANE THANE 400607 100 150.00 7 IN30177410302360 A CHANDRAN G 9 TAC NAGAR TUTICORIN 628008 1 2.00 8 39588 A GANESH 61, EGMORE HIGH ROAD EGMORE CHENNAI 600008 100 150.00 9 18768 A JAYA PRAKASH M-191 IX TH CROSS ST 3RD MAIN RD T V R NAGAR THIRUVANMIYUR CHENNAI 600041 200 300.00 10 IN30290241783218 A K CHORDIA 61 SANJEEVAPPA COLONY 1ST FLOOR JAI BHARATH NAGAR BANGALORE 560033 350 525.00 11 18949 A K SOBHANA SEKHAR W/O C K SEKHARAN PLOT 16 D NO 10 NARMADA NAGAR GAJALAKSHMI ST ULLKARAM CHENNAI 600091 100 150.00 12 34892 A K VASUMATHY B1/51, VASUNDARA APARTMENTS S V ROAD BORIVILI (W) MUMBAI 400092 100 150.00 13 27572 A KUMAR TYPE II/11B, TATA COLONY, AZIZ BAUG CHEMBUR BOMBAY 400074 100 150.00 14 18143 A L NAVEEN 40/A 65 MAIN 11TH CROSS 3RD PHASE J P NAGAR BANGALORE 560078 100 150.00 15 26068 A LAKSHMI KANTHAM MAMATA APARTMENTS(A2) -

Thirunelveli

Thirunelveli Name Mobile Telephone Products Address Place 7/173,Santhana Dimethoate,carbofuran, Mariamman kovil M.Thagasamy 9994105006 Azadirachtin street Alangulam-627-851 Cartap Hydrocloride, Selvi store 1/52, S.Manickrajan 9789559050 Carbendazim,metiram Nettur road Alangulam 627-851 Sri meenambigai Captan,dimethoate,End vilas 1/125 Sundara P.Subramaniyan 9442124871 osulfan vinayagar kovil street Maranthai N. Chokkalingam Atrazine,Lambda,Azoxys Pillai sons 10/30 B C. Nallakannu 9486590700 4633247141 trobin,Endosulfan church street Uthumalai 627860 M/s .Elumalaiyan monocrotophos,malathi store 1/200 main A.Nallasivam 9865035313 on,chlorpyriphos road Melamaruthappapuram-627860 M/S Subbulakshmi Atrazin,Buprofezin,carb Traders 7/595,main T.P Seetharaman 9486728132 4633288132 oxin,Glyphosate road Venkatesvarapuram-627867 Atrazine,captan,dimeth Sankar store 1/108 G. Sanakar 9787254214 oate.metiram ,chavadi street Maranthai M/s ganesh traders Sulphur,Ethion,qunialph 5/517,sankarankovil G. Kaleeswari 9442330469 os,fipronil road Uthumalai -627860 Mathesh Karthikeyan store Carbaryl,profenofos,Car 2/167,pillaiyar kovil N. Muthuraj 9788124209 bendazim street Kadanganeri 627854 Sri Venkadesvara Agency 5/223-1 Carbendazim,Cypermet Natarajan sannathi P.Dhiraviam 9600810018 hrin,metalazyl street Aladipatty-627-853 G.R Ulhavar maiyam Phosphomidon,Triazop 14/45,TDTA School M.Gopi 8489334044 hos,phorate, street Alangulam-627-851 Maran store chlorpyrifos,Azoxystrobi 9/88,Aranmanai,stre K.Chidambaram 9942148038 247409 n,monocrotophos et Uthumalai -627860 Raja store Novaluron,Atrazine.Alu 5/6,mariamman P.Raja 9842328505 minium,Malathion kovil street Kuruvankottai-627-853 Carbendazim,Atrazine,C Harish Traders S.Govindarajan 9488378747 aptan,Ziram 7/385,main road Venkatesvarapuram-627867 Jean Traders Atrazine,metalatxyl,end 14/54,R.C Church Jean Sornapathi 9442395077 osulfan street Alangulam-627-851 Penconazole,Endosulfa M/S Hari store 84- S. -

Maya Jaya Tv Serial Episode 1

Maya Jaya Tv Serial Episode 1 Maya Jaya Tv Serial Episode 1 1 / 4 2 / 4 30 Pm to 02 00 Pm, 03 00 Pm to 03 30 Pm Kasu Mela – Part 1 | Game Segment Jaya TV Pongal 2020 Special Show Watch Online, Kasu Mela – Part 1 | Game Segment Jaya TV Pongal 2020 Special Show Watch Online, Pongal Special Jaya TV Show Watch online, watch Pongal Special show Jaya TV Pongal Special Watch Online, Watch Pongal Special Show, Keepass for mac 2016.. The music was composed by D Tamil-language television programs Revolvy Brain revolvybrain revolvybrain’s feedback about Maya TV series: A woman gets ready to leave for a get together and finds her dead in their room.. watch Pongal Special Function Jaya TV Pongal Special Watch Online, Watch Jaya TV Pongal Special function, Pongal Special Jaya celebration in conclusion and, first of all, most of all, most noteworthy, another, furthermore, finally, addition, most of all, noteworthy, especially relevant, in seems like, maybe, probably, almost, furthermore, finally,in conclusion and, first of all, most of all, most noteworthy, another, furthermore, finally, addition, most of all, noteworthy, especially relevant, inMaya Jaya Tv Serial Episode 1furthermore, finally, seems like, maybe, probably, almost most of all, noteworthy, especially relevant, in addition, finally, seems like, furthermore, , maybe, probably, almostSorry I can't help more. 1. maya jaya tv serial episode 1 Deivamagal Serial brings all fame to the Vani Bhojan and it was one of the most watching serials in Tamilnadu.. Before the pre- filmed continuing series became the dominant dramatic form on American television, multiple cameras can take different shots of a live situation as the action unfolds chronologically and is suitable for shows which require a live audience. -

Jyoti Ghai 84XXXXXX67 Dalchini Restaurant Gurgaon Haryan

Name Mobile No. Shop Name City State - 76XXXXXX61 Mobile Assecories - - Jyoti Ghai 84XXXXXX67 Dalchini Restaurant Gurgaon Haryana - Suryaonlineseva Palvancha Telangana Prince Jain 90XXXXXX32 Jain Foto State Aminagar Sarai Uttar Pradesh - 91XXXXXX84 Jhankar Music Bhopal Madhya Pradesh Raju 91XXXXXX39 Raju Communication New Delhi Delhi Desai Yash 97XXXXXX29 Blooming Breadzz Ahmedabad Gujarat Soruban 98XXXXXX09 Universale Kanchipuram Tamil Nadu - 98XXXXXX67 - - - - 99XXXXXX37 - - - - 93XXXXXX83 Tathya Mitra Kendra - - - 99XXXXXX23 Pizza Da Dhaba Cafe Sahibzada Ajit Singh Nagar Punjab 98XXXXXX36 Customer Service Point Bathinda Punjab Vasudev Sharma 90XXXXXX20 Salasar Mishthan Bhandar Jaipur Rajasthan 99XXXXXX99 Gaytri Net Cafe Makegain Bk Maharashtra Utam Chand 98XXXXXX67 Adarsh Medical Bengaluru Karnataka Ketan Gaur 94XXXXXX06 Balaji Confectionary Aligarh Uttar Pradesh Avinash Kumar Ankur 78XXXXXX70 Bigg Boss Gurgaon Haryana Rahul Rathore 91XXXXXX95 Adarsh Namkin Corner Ratlam Madhya Pradesh - 99XXXXXX05 Sky Broadband - - - 95XXXXXX33 Salon De Manik - - - 90XXXXXX79 - Bengaluru Karnataka 99XXXXXX77 Sharma Telecome South Delhi Delhi Hemant Kumar 98XXXXXX62 Om Sai Provision Store Ghaziabad Uttar Pradesh - 98XXXXXX12 Virender Kirana - - Santosh Kumar L 99XXXXXX82 Suguna Daily Fressh Bengaluru Karnataka - 99XXXXXX32 Path Care Labs Pvt.Ltd - - Shubham Diwakar 70XXXXX027 Shubham Telecom Kanpur Uttar Pradesh - 90XXXXXX00 Monginis Pimpri-Chinchwad Maharashtra Harikrishna Chava 98XXXXXX06 Mat Fruit Juice Point Hyderabad Telangana Anupam Mohta 98XXXXXX32 -

List of Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend to Be Transferred to IEPF Authority.XLS

Unpaid_Data_1 LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS WHOSE UNPAID OR UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND ARE LIABLE TO BE TRANSFERRED TO INVESTOR EDUCATION PROTECTION FUND (IEPF) First Name Middle Name Last Name Father/Husband NameAddress PINCode Folio Number No of Shares Amount Due(in Rs.) SHUNMUGAVELU NADARVS SRIVSUBBIAH 357-MOGUL STREET, RANGOON NA P00000084 11 7700 VELLIAH NADARS SRIVSWAMIDASSRANGOON NA P00000090 3 2100 THAVASI NADARKP SRIKPERIANNA 40-28TH STREET, RANGOON NA P00000091 2 1400 DAWSON NADARA NAPPAVOO C/O SRI.N.SAMUEL, PRASER STREET, POST OFFICE, RANGOON-1 NA P00000095 1 700 VIJAYA DORAISAMY GRAMONEYT SRITYAGAMBARA 1-THANDAVARAJA GRAMONEY STREET, THANDAYARPET, CHENNAI TAMIL NADU 600021P00000122 2 1400 RATHINAVEL NADAR SRIMAGVKUMARANDI122-SOUTH MASI STREET, MADURAI 625001P00000131 5 3500 VADIVEL NADARP PERIYANNA USILAMPATTI, THIRUMANGALAM MADURAI D.T. 625706P00000139 5 3500 PONNIAH NADARS SWAMIDOSS 151-PRINCE STREET, COLOMBO NA P00000233 5 3500 ERATHNASAMY NADARAPCA ALLIMUTHU 6-VENKATASALU NAIDU LANE, KAMARAJAR SALAI, MADURAI 625009 P00000234 31 21700 GURUSAMY NADARMR SRIMRAMASAMY 1-KUYAVANPALAYAM 3RD LANE, MADURAI 625009P00000250 3 2100 AYAPPA NADARA ANANTHAPPA 150-MONTGOMERY STREET, RANGOON NA P00000315 10 7000 GNANAMUTHU NADARAP PAKIYANATHA SETHER ROAD, MULLERIAH, ANGODIAN P.O. COLOMBO NA P00000324 1 700 MADASAMY NADARS SHUNMUGA 237 MERCHANT STREET, BOTATAUNG, RANGOON NA P00000336 5 3500 SAMUEL DAVAMANI NADARG THANDAPANI HOSPITAL, NORTH RETHA VEETHI, TENKASI 627811P00000351 2 1400 THANGAPPA NADARM VSMADASAMY ANAND BHAVAN, 13 VASANTHA NAGAR, MADURAI 625003 P00000360 5 3500 SUBBIAH NADARSM MUTHIAH 39 WATER FALL ROAD, PENANG F.M.S. MALAYA NA P00000377 25 17500 VELAYUTHA NADARAS ASUBRAMANIA 177-C BAZAAR ARGYIL ROAD, PENANG NA P00000384 10 7000 SHUNMUGAPANDIA NADARKPA KPARUNACHALA VIRUDHUNAGAR 626001 P00000440 2 1400 ATHIAPPAN NADARSM SMMUTHIAH C/O K.KANDIAH, 85 BATHULANCHANG ROAD, PENANG NA P00000470 25 17500 PAULV GVETHANAYAGAM35 BENCOOLEN STREET, SINGAPORE NA P00000494 10 7000 JOHN RAJAMONY SRIARUMAINAYAGAMTHALAKULAM, NORTH ARIYANAYAGAPURAM VILLAGE, SINGAMPALAI P.O. -

INFORMATION UNDER SECTION 4(1)A of RTI ACT-2005 VAT RETURN RECORDS PERTAINING to 2007-08 O/O LVO-055A, BANGALORE Sl.No

INFORMATION UNDER SECTION 4(1)A OF RTI ACT-2005 VAT RETURN RECORDS PERTAINING TO 2007-08 O/O LVO-055A, BANGALORE Sl.No. File No. Subject Year of Date of Category A Date on which Name of the official Date on which Name of the Record Maintenance Year of Date of Name of the Name of the opening closing the file B the file is sent who has sent the file the file is Officer Disposal destruction officer who has officer who has the file C to record room to the Record Room received in the Incharge of Rack No. Bundle Year of the ordered for destroyed the D record room Record No. record destruction of record E Room the record 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11a 11b 11c 12 13 14 15 1 29690354701 21ST CENTURY 1/4/2007 31/03/2008 B 20/12/2011 M.Anitha 21/12/2011 Chamaiah 1-A 1 2007-08 2 29420394959 21ST CENTURY DEVELOPPERS& ENGINEERS 1/4/2007 31/03/2008 B 20/12/2011 Sashidhar 21/12/2011 Chamaiah 1-A 1 2007-08 3 29930126231 A & P COLOUR CO 1/4/2007 31/03/2008 B 20/12/2011 M.Anitha 21/12/2011 Chamaiah 1-A 1 2007-08 4 29580703040 A D N HARDWARE 1/4/2007 31/03/2008 B 20/12/2011 Prasanna.J 21/12/2011 Chamaiah 1-A 1 2007-08 5 29400726128 A F LUBRICANT 1/4/2007 31/03/2008 B 20/12/2011 M.Anitha 21/12/2011 Chamaiah 1-A 1 2007-08 6 29580745420 A M WOOD WORKS 1/4/2007 31/03/2008 B 20/12/2011 Prasanna.J 21/12/2011 Chamaiah 1-A 1 2007-08 7 29680743628 A N FABRICATION 1/4/2007 31/03/2008 B 20/12/2011 M.Anitha 21/12/2011 Chamaiah 1-A 1 2007-08 8 2926076040 A R K AGENCIES 1/4/2007 31/03/2008 B 20/12/2011 Prasanna.J 21/12/2011 Chamaiah 1-A 1 2007-08 9 29150463444 A Syed Sajjad 1/4/2007 31/03/2008 B 20/12/2011 Ramachandra 21/12/2011 Chamaiah 1-A 1 2007-08 10 29830743594 A.A.Stores 1/4/2007 31/03/2008 B 20/12/2011 Ramachandra 21/12/2011 Chamaiah 1-A 1 2007-08 11 29130475774 A.G.Electricals 1/4/2007 31/03/2008 B 20/12/2011 Ramachandra 21/12/2011 Chamaiah 1-A 1 2007-08 12 29300754604 A.H.R. -

奏錦i斂 J砏.«.N G鍊p A. §Aq橾 A. 社耋 1 2 3A 3B 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11A

INFORMATION UNDER SECTION 4(1a) OF TH E RTI ACT VAT RETURN RECORDS FOR THE YEAR 2007-08 PÀqÀvÀ ¤ªÀðºÀuÉ «µÀAiÀÄ Jï.«.N PÀqÀvÀ PÀqÀvÀ PÀqÀvÀzÀ PÀqÀvÀªÀ£ÀÄß PÀqÀvÀªÀ£ÀÄß PÀqÀvÀªÀ£ÀÄß C©üÉÃSÁ® PÀqÀvÀ PÀqÀvÀ PÀqÀvÀ PÀqÀvÀ PÀæªÀÄ zÁRÁwUÀ¼À ªÀVðPÀgÀt C©üÉÃSÁ®Ai C©üÉÃSÁ® C©üÉÃSÁ®Ai AiÀÄzÀ £Á±ÀUÉƽ¸À £Á±À¥Àr¹z ¥ÁægÀA©ü¹zÀ CAvÀåUÉƽ¹ §AqÀï «ÉêÁj £Á±ÀUÉƽ¹ ¸ÀASÉå PÀqÀvÀ ¸ÀASÉå ºÉ¸ÀgÀÄ J © ¹ r ÀÄPÉÌ AiÀÄPÉÌ ÀÄzÀ°è ¥ÀqÉzÀ C¢üPÁj gÁåPï £ÀA. ªÀµÀð ®Ä À C¢üPÁj ªÀµÀð zÀ ¢£ÁAPÀ £ÀA. ªÀµÀð zÀ ¢£ÁAPÀ E PÀ¼ÀÄ»¹zÀ PÀ¼ÀÄ»¹zÀ ¢£ÁAPÀ ºÉ¸ÀgÀÄ DzÉò¹zÀ ºÉ¸ÀgÀÄ 1 2 3A 3B 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11A 11B 11C 12 13 14 15 K V Rack A GUDARANGAPPA AND CO, sira 172 C 01-07-2012 Murlidhar,T 01-07-2012 Prabhakar 1 2007-08 No. 6 1 29770104397 04-01-2007 21/04/2008 ypeist FDA K V ADISHESHA GOBBARADA Rack 172 C 01-07-2012 Murlidhar,T 01-07-2012 Prabhakar 1 2007-08 DEPOT,sira No. 6 2 29940104643 04-01-2007 21/04/2008 ypeist FDA K V Rack AFREEN TRADERS,sira 172 C 01-07-2012 Murlidhar,T 01-07-2012 Prabhakar 1 2007-08 No. 6 3 29790275106 04-01-2007 21/04/2008 ypeist FDA K V Rack AKSHAY TYERS,sira 172 C 01-07-2012 Murlidhar,T 01-07-2012 Prabhakar 1 2007-08 No. 6 4 29700275204 04-01-2007 21/04/2008 ypeist FDA K V Rack AMBIKA ELETRICALS,sira 172 C 01-07-2012 Murlidhar,T 01-07-2012 Prabhakar 1 2007-08 No.