I'm a Real Inuk; I Love to Sing! Interactions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

06-07-18 the Brand

June 7, 2018 • Lowry High School • Winnemucca, NV To the class of 2018 Senior year the good old days when everything was simple and white and most of us probably got painted in the consists of a lot of you had not a worry in the world. One day you will process as well. Monday was Senior Sunrise. We lasts. One day, you will be at your be packing up your bags and hugging your parents woke up when it was still dark, took our blankets last homecoming, your last game with your team, goodbye. One day you will no longer be in high to the football field and chilled with our friends as taking your last test, receiving your last report card, school. the sun rose. Sadly, it was a little more cloudy than dressing out for weights for the very last time, and A lot of these “one days” have already happened sunny but that didn’t stop us from having a good eating your last high school lunch. One day, you for most of us while some are soon to happen. And time. will have your last wild Saturday night with all of you might ask yourself: “Where did the time go?” It Our girls won their fourth powder puff game. your friends. And then one day you will close your seems like yesterday we stepped into this school as Our last homecoming was Disneyland themed. locker for the very last time and never come back. scared little freshmen for the very first time think- We dressed up in blue and pink. -

Small Business Saturday Is Coming!

Small Business Saturday is Coming! Shop Granville First is Saturday, November 24 As a small business, it's tough to compete with Black Friday deals. Consider sharing some background on why Small Business Saturday is important, and offer an incentive to bring customers through the door. Whether it's a discount, BOGO, or free gift, customers will appreciate the offer and return the appreciation by shopping with you. We all know that Small Biz Rocks in Granville county. This is the year we prove it! 2018 Shop Granville First's theme is Small Biz Rocks, and it's going to be a fun, interactive event. How it works: every participating small business in Granville county will be provided a customized Small Biz Rocks rock to place in their store/office. Shoppers/visitors are encouraged to search for the rock and when it's found, present it to the business owner. Shoppers can snap a pic and post to social media, or be entered into your drawing, or given a discount or bounce-back coupon-- whatever you choose to award--it's totally up to you! Create your plan: When creating your plan, consider the following ideas/thoughts. Why should people shop with you on Small Business Saturday this year? How can I collaborate with another local business? Create a great offer by adding words like "free" "personalized" "complimentary" or "customized". A sense of urgency often helps readers take an action, so think about inserting phrases like "for a limited time only" or "only 7 remaining!" Your assignment: It's time to put your plan into action. -

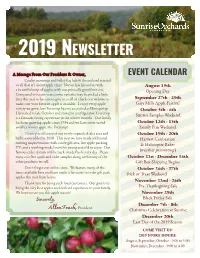

2019 Newsletter

Front page: Allen’s greeting, something new 2019 NEWSLETTER A Message From Our President & Owner, EVENT CALENDAR Cooler mornings and valley fog below the orchard remind us all that it’s about apple time! Nature has blessed us with August 19th a beautiful crop of apples with exceptionally good fruit size. Opening Day Compared to recent years, some varieties may be picked a little later this year so be sure to give us a call or check our website to September 27th - 29th make sure your favorite apple is available. I enjoy every apple Gays Mills Apple Festival variety we grow, but Evercrisp has me as excited as Honeycrisp. October 5th - 6th Harvested in late October and stored in a refrigerator, Evercrisp Sunrise Samples Weekend is a fantastic eating experience in the winter months. Our family has been growing apples since 1934 and we have never tasted October 12th - 13th another winter apple like Evercrisp! Family Fun Weekend I hope you all enjoyed our newly expanded sales area and October 19th - 20th bathrooms added in 2018. This year we have made additional Harvest Celebration exciting improvements with a new gift area, live apple packing & Helicopter Rides TV, and a working model train for young and old to enjoy. Our famous cider donuts will be back- made fresh every day. Please (weather permitting ) enjoy our free apple and cider samples along with many of the October 21st - December 16th other products we sell. Gift Box Shipping Begins Don’t forget our online store. We feature many of the October 26th - 27th items available here and have made it far easier to order gift pack Trick or Treat Weekend apples this year from home. -

Toward Sustainable Arctic Shipping: Perspectives from China

sustainability Article Toward Sustainable Arctic Shipping: Perspectives from China Qiang Zhang , Zheng Wan * and Shanshan Fu College of Transport and Communications, Shanghai Maritime University, Shanghai 201306, China; [email protected] (Q.Z.); [email protected] (S.F.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 21 September 2020; Accepted: 27 October 2020; Published: 29 October 2020 Abstract: As a near-Arctic state and a shipping power, China shows great interest in developing polar shortcuts from East Asia to Europe against the background of shrinking Arctic sea ice. Due to the Arctic’s historic inaccessibility and corresponding vulnerable ecosystems, Arctic shipping activities must be carried out sustainably. In this study, a content analysis method was adopted to detect Chinese perspectives toward sustainable Arctic shipping based on qualitative data collected from the websites of several Chinese government agencies. Results show that, first, China emphasizes the fundamental role played by scientific expeditions and studies in developing Arctic shipping routes. Second, China encourages its shipping enterprises to conduct commercial and regularized Arctic voyages and intends to strike a good balance between shipping development and environmental protection. Third, China actively participates in Arctic shipping governance via extensive international cooperation at the global and regional levels. Several policy recommendations on how China can develop sustainable Arctic shipping are proposed accordingly. Keywords: sustainability; Arctic shipping; governance; China 1. Introduction Arctic sea ice is undergoing an extraordinary transition from generally thick multi-year sea ice to seasonal sea ice that is younger and less thick because of global warming [1]. Specifically, the volume of Arctic sea ice has declined by 75% since 1979 [1]. -

Bishop Otter College Guild Newsletter 2018

Bishop Otter College Guild Newsletter 2018 Guild Newsletter 2018 | 3 Welcome to the Bishop Otter College Guild Newsletter 2018 We are very excited to announce the return of the Jean Lurçat tapestry to the Chapel of the Ascension after six years. The tapestry had not been taken down since its installation in the early 1960s and although it was in very good condition it showed evidence of dye fading due to over exposure to high light levels, a few areas of abraded weft particularly at shoulder and arm height and it was very dusty. The work undertaken by conservator Zenzie Tinker (pictured below) has addressed the damage caused by dust and abrasion and the tapestry has been raised to reduce the risk of people brushing against it when using the altar. The issue of UV damage remains but the tapestry will now be checked annually by the conservator to assess its condition. The Chapel of the Ascension has played a central role in the life of the University since its creation and we are thrilled to be able to showcase the tapestry once more. We invite our alumni back to campus to view the tapestry either before or during the Bishop Otter Guild Reunion. If you would like to visit please get in touch with the Alumni Team who will be happy to arrange a visit for you. 01243 812171 [email protected] 2 | Guild Newsletter 2018 Bishop Otter College Guild President Professor Clive Behagg Vice-Presidents Dr Colin Greaves Professor Philip E D Robinson Honorary Secretary Mr Marten Lougee 11 Meadow Close Cononley, Keighley West Yorkshire BD20 8LZ 01535 636487 -

Revisiting Trans-Arctic Maritime Navigability in 2011–2016 from the Perspective of Sea Ice Thickness

remote sensing Article Revisiting Trans-Arctic Maritime Navigability in 2011–2016 from the Perspective of Sea Ice Thickness Xiangying Zhou 1,2, Chao Min 1,2 , Yijun Yang 1,2, Jack C. Landy 3,4, Longjiang Mu 5 and Qinghua Yang 1,2,* 1 Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Zhuhai), School of Atmospheric Sciences, Sun Yat-sen University, Zhuhai 519082, China; [email protected] (X.Z.); [email protected] (C.M.); [email protected] (Y.Y.) 2 Key Laboratory of Tropical Atmosphere-Ocean System, Ministry of Education, Zhuhai 519082, China 3 Department of Physics and Technology, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, 9037 Tromsø, Norway; [email protected] 4 Bristol Glaciology Centre, School of Geographical Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol BS8 1 HB, UK 5 Qingdao Pilot National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology, Qingdao 266237, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Arctic navigation has become operational in recent decades with the decline in summer sea ice. To assess the navigability of trans-Arctic passages, combined model and satellite sea ice thickness (CMST) data covering both freezing seasons and melting seasons are integrated with the Arctic Transportation Accessibility Model (ATAM). The trans-Arctic navigation window and transit time are thereby obtained daily from modeled sea ice fields constrained by satellite observations. Our results indicate that the poorest navigability conditions for the maritime Arctic occurred in 2013 and 2014, particularly in the Northwest Passage (NWP) with sea ice blockage. The NWP has generally Citation: Zhou, X.; Min, C.; Yang, Y.; exhibited less favorable navigation conditions and shorter navigable windows than the Northern Landy, J.C.; Mu, L.; Yang, Q. -

Dresden Makes Winter Sparkle

Tourism Dresden makes winter sparkle www.dresden.de/events Visit Dresden e City of Christmas A Dresden welcome If you like Christmas, you’ll love Dresden. A grand total of twelve completely different Christmas markets, from the by no means Dark Ages to the après- ski charm of Alpine huts, makes for wonderfully conflicting decisions. Holiday sounds fill the air throughout the city. From the many oratorios to Advent, organ and gospel concerts, Dresden’s churches brim with FIVE STARS IN festive insider tips. Christmas tales also come to life in the city’s theatres whilst museums PREMIUM LOCATION host special exhibitions and boats bejewelled with lights glide along the Elbe. If only Christmas could last more than just a few weeks … Dresden Christmas markets ................................................................. 4 INFORMATION & OPENING OFFER T 036461-92000 I [email protected] Dresden winter magic ........................................................................... 8 www.elbresidenz-bad-schandau.net Concerts, Theatre, Shows..................................................................... 10 Boat Trips, Tours ................................................................................... 16 Exhibitions ............................................................................................ 18 Christmas through the Region ........................................................... 20 Shopping at the Advent season .......................................................... 23 Package offer: Advent in -

Taltheilei Houses, Lithics, and Mobility

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2012-09-06 Taltheilei houses, lithics, and mobility Pickering, Sean Joseph Pickering, S. J. (2012). Taltheilei houses, lithics, and mobility (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/27975 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/177 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Taltheilei Houses, Lithics, and Mobility by Sean J. Pickering A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY CALGARY, ALBERTA SEPTEMBER, 2012 © Sean J. Pickering 2012 Abstract The precontact subsistence-settlement strategy of Taltheilei tradition groups has been interpreted by past researchers as representing a high residential mobility forager system characterized by ephemeral warm season use of the Barrenlands environment, while hunting barrenground caribou. However, the excavation of four semi-subterranean house pits at the Ikirahak site (JjKs-7), in the Southern Kivalliq District of Nunavut, has challenged these assumptions. An analysis of the domestic architecture, as well as the morphological and spatial attributes of the excavated lithic artifacts, has shown that some Taltheilei groups inhabited the Barrenlands environment during the cold season for extended periods of time likely subsisting on stored resources. -

The Scottish Banner

thethethe ScottishScottishScottish Banner BannerBanner 44 Years Strong - 1976-2020 www.scottishbanner.com A’ Bhratach Albannach Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 VolumeVolumeVolume 44 36 Number36 Number Number 6 11 The 11 The world’sThe world’s world’s largest largest largest international international international Scottish Scottish Scottish newspaper newspaper newspaper December May May 2013 2013 2020 Celebrating US Barcodes Hebridean history 7 25286 844598 0 1 The long lost knitting tradition » Pg 13 7 25286 844598 0 9 US Barcodes 7 25286 844598 0 3 7 25286 844598 0 1 7 25286 844598 1 1 The 7 25286 844598 0 9 Stone of 7 25286 844598 1 2 Destiny An infamous Christmas 7 25286 844598 0 3 repatriation » Pg 12 7 25286 844598 1 1 Sir Walter’s Remembering Sir Sean Connery ............................... » Pg 3 Remembering Paisley’s Dryburgh ‘Black Hogmanay’ ...................... » Pg 5 What was Christmas like » Pg 17 7 25286 844598 1 2 for Mary Queen of Scots?..... » Pg 23 THE SCOTTISH BANNER Volume 44 - Number 6 Scottishthe Banner The Banner Says… Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 Publisher Contact: Scottish Banner Pty Ltd. The Scottish Banner Editor PO Box 6202 For Auld Lang Syne Sean Cairney Marrickville South, NSW, 2204 forced to cancel their trips. I too was 1929 in Paisley. Sadly, a smoking EDITORIAL STAFF Tel:(02) 9559-6348 meant to be over this year and know film canister caused a panic during Jim Stoddart [email protected] so many had planned to visit family, a packed matinee screening of a The National Piping Centre friends, attend events and simply children’s film where more than David McVey take in the country we all love so 600 kids were present. -

Recent Declines in Warming and Vegetation Greening Trends Over Pan-Arctic Tundra

Remote Sens. 2013, 5, 4229-4254; doi:10.3390/rs5094229 OPEN ACCESS Remote Sensing ISSN 2072-4292 www.mdpi.com/journal/remotesensing Article Recent Declines in Warming and Vegetation Greening Trends over Pan-Arctic Tundra Uma S. Bhatt 1,*, Donald A. Walker 2, Martha K. Raynolds 2, Peter A. Bieniek 1,3, Howard E. Epstein 4, Josefino C. Comiso 5, Jorge E. Pinzon 6, Compton J. Tucker 6 and Igor V. Polyakov 3 1 Geophysical Institute, Department of Atmospheric Sciences, College of Natural Science and Mathematics, University of Alaska Fairbanks, 903 Koyukuk Dr., Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 2 Institute of Arctic Biology, Department of Biology and Wildlife, College of Natural Science and Mathematics, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, P.O. Box 757000, Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (D.A.W.); [email protected] (M.K.R.) 3 International Arctic Research Center, Department of Atmospheric Sciences, College of Natural Science and Mathematics, 930 Koyukuk Dr., Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 4 Department of Environmental Sciences, University of Virginia, 291 McCormick Rd., Charlottesville, VA 22904, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 5 Cryospheric Sciences Branch, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Code 614.1, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 6 Biospheric Science Branch, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Code 614.1, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (J.E.P.); [email protected] (C.J.T.) * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-907-474-2662; Fax: +1-907-474-2473. -

Dresden.De/Events Visit Dresden Christmas Magic in the Dresden Elbland Region

Winter Highlights 2018/2019 www.dresden.de/events Visit Dresden Christmas magic in the Dresden Elbland region Anyone who likes Christmas will love Dresden. Eleven very distinct Christmas markets make the metropolis on the Elbe a veritable Christmas city. Christmas in Dresden – that also means festive church concerts, fairy tale readings and special exhibitions. Or how about a night lights cruise on the Elbe? Just as the river itself connects historic city-centre areas with gorgeous landscapes, so the Christmas period combines the many different activities across the entire Dresden Elbland region into one spellbinding attraction. 584th Dresden Striezelmarkt ..................................................... 2 Christmas cheer everywhere Christmas markets in Dresden .................................................. 4 Christmas markets in the Elbland region ................................... 6 Events November 2018 – February 2019 ............................................... 8 Unique experiences ................................................................... 22 Exhibitions ................................................................................. 24 Advent shopping ....................................................................... 26 Prize draw .................................................................................. 27 Packages .................................................................................... 28 Dresden Elbland tourist information centre Our service for you ................................................................... -

Spanning the Bering Strait

National Park service shared beringian heritage Program U.s. Department of the interior Spanning the Bering Strait 20 years of collaborative research s U b s i s t e N c e h UN t e r i N c h UK o t K a , r U s s i a i N t r o DU c t i o N cean Arctic O N O R T H E L A Chu a e S T kchi Se n R A LASKA a SIBERIA er U C h v u B R i k R S otk S a e i a P v I A en r e m in i n USA r y s M l u l g o a a S K S ew la c ard Peninsu r k t e e r Riv n a n z uko i i Y e t R i v e r ering Sea la B u s n i CANADA n e P la u a ns k ni t Pe a ka N h las c A lf of Alaska m u a G K W E 0 250 500 Pacific Ocean miles S USA The Shared Beringian Heritage Program has been fortunate enough to have had a sustained source of funds to support 3 community based projects and research since its creation in 1991. Presidents George H.W. Bush and Mikhail Gorbachev expanded their cooperation in the field of environmental protection and the study of global change to create the Shared Beringian Heritage Program.