Corporeal Territories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

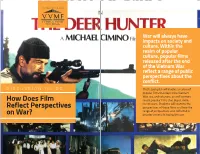

VVMF Education Guide

FOUNDERS OF THE WALL ECHOES FROM THE WALL War will always have impacts on society and culture. Within the realm of popular culture, popular films released after the end of the Vietnam War reflect a range of public perspectives about the conflict. DISCUSSION GUIDE This lesson plan will involve a review of popular films that depict the Vietnam War, era, and veterans, as well as more How Does Film recent popular films that depict more recent wars. Students will examine the Reflect Perspectives perspectives of these films and how the range of perspectives was reflected in on War? broader society following the war. Download the Perspectives on War? Reflect Does Film How Accompanying Powerpoint Presentation for use in the classroom > PRE-VISIT ACTIVITY 1 Films from Vietnam Ask students to create a list of movies they have seen that have a focus on the Vietnam War, era, or veterans (for a list, see: http://www.vvmf.org/teaching-vietnam). Ask each student to choose a favorite from the list and explain his/her reasoning for why it’s his/her favorite. If a student hasn’t see any—ask him or her to choose one to watch at home. For that movie, ask students to answer the following questions: • What issues are depicted in the movie? • Would you say that the movie takes a position on the war? What evidence supports your answer? • What part or parts of the movie struck you? Why? • What do you think someone who had no background on the Vietnam War or era would take away about it from this movie? PRE-VISIT ACTIVITY 2 Vietnam in Media Ask students to poll 10 of their siblings, friends, or even parents: What are the top two NOTE TO sources from which they have any understanding of the TEACHER Vietnam War and era? Place a tally mark beside each response. -

The Cinema of Oliver Stone

Interviews Stone on Stone Between 2010 and 2014 we interviewed Oliver Stone on a number of occasions, either personally or in correspondence by email. He was always ready to engage with us, quite literally. Stone thrives on the cut- and- thrust of debate about his films, about himself and per- ceptions of him that have adorned media outlets around the world throughout his career – and, of course, about the state of America. What follows are transcripts from some of those interviews, with- out redaction. Stone is always at his most fascinating when a ques- tion leads him down a line of theory or thinking that can expound on almost any topic to do with his films, or with the issues in the world at large. Here, that line of thinking appears on the page as he spoke, and gives credence to the notion of a filmmaker who, whether loved or loathed, admired or admonished, is always ready to fight his corner and battle for what he believes is a worthwhile, even noble, cause. Oliver Stone’s career has been defined by battle and the will to overcome criticism and or adversity. The following reflections demonstrate why he remains the most talked about, and combative, filmmaker of his generation. Interview with Oliver Stone, 19 January 2010 In relation to the Classification and Ratings Administration Interviewer: How do you see the issue of cinematic censorship? Oliver Stone: The ratings thing is very much a limited game. If you talk to Joan Graves, you’ll get the facts. The rules are the rules. -

Gender, Dissenting Subjectivity and the Contemporary Military Peace Movement in Body of War

International Feminist Journal of Politics ISSN: 1461-6742 (Print) 1468-4470 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rfjp20 Gender, Dissenting Subjectivity and the Contemporary Military Peace Movement in Body of War Joanna Tidy To cite this article: Joanna Tidy (2015) Gender, Dissenting Subjectivity and the Contemporary Military Peace Movement in Body of War, International Feminist Journal of Politics, 17:3, 454-472, DOI: 10.1080/14616742.2014.967128 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14616742.2014.967128 Published online: 02 Dec 2014. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 248 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 2 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rfjp20 Download by: [University of Massachusetts] Date: 28 June 2016, At: 13:24 Gender, Dissenting Subjectivity and the Contemporary Military Peace Movement in Body of War JOANNA TIDY School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies (SPAIS), University of Bristol, UK Abstract ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- This article considers the gendered dynamics of the contemporary military peace move- ment in the United States, interrogating the way in which masculine privilege produces hierarchies within experiences, truth claims and dissenting subjecthoods. The analysis focuses on a text of the movement, the 2007 documentary -

Public Politics/Personal Authenticity

PUBLIC POLITICS/PERSONAL AUTHENTICITY: A TALE OF TWO SIXTIES IN HOLLYWOOD CINEMA, 1986- 1994 Oliver Gruner Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. University of East Anglia School of Film and Television Studies August, 2010 ©This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis, nor any information derived therefrom, may be published without the author’s prior, written consent. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 5 Chapter One “The Enemy was in US”: Platoon and Sixties Commemoration 62 Platoon in Production, 1976-1982 65 Public Politics/Personal Authenticity: Platoon from Script to Screen 73 From Vietnam to the Sixties: Promotion and Reception 88 Conclusion 101 Chapter Two “There are a lot of things about me that aren’t what you thought”: Dirty Dancing and Women’s Liberation 103 Dirty Dancing in Production, 1980-1987 106 Public Politics/Personal Authenticity: Dirty Dancing from Script to Screen 114 “Have the Time of Your Life”: Promotion and Reception 131 Conclusion 144 Chapter Three Bad Sixties/ Good Sixties: JFK and the Sixties Generation 146 Lost Innocence/Lost Ignorance: Kennedy Commemoration and the Sixties 149 Innocence Lost: Adaptation and Script Development, 1988-1991 155 In Search of Authenticity: JFK ’s “Good Sixties” 164 Through the Looking Glass: Promotion and Reception 173 Conclusion 185 Chapter Four “Out of the Prison of Your Mind”: Framing Malcolm X 188 A Civil Rights Sixties 191 A Change -

The Vietnam War in the American Mind, 1975-1985 Mark W

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 8-1989 Half a memory : the Vietnam War in the American mind, 1975-1985 Mark W. Jackley Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Recommended Citation Jackley, Mark W., "Half a memory : the Vietnam War in the American mind, 1975-1985" (1989). Master's Theses. Paper 520. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Half A Memory: The Vietnam War In The American Mind, 1975 - 1985 Mark W. Jackley Submitted for the Degree of Master of Arts in History University of Richmond, 1989 Dr. Barry Westin, Thesis Director This study attempts to show how Americans in general remembered the Vietnam War from 1975 to 1985, the decade after it ended. A kind of social history, the study concentrates on the war as remembered in the popular realm, examining novels as well as nonfiction, poetry, plays, movies, articles in political journals, songs, memorials, public opinion polls and more. Most everything but academic history is discussed. The study notes how the war's political historY. was not much remembered; the warrior, not the war, became the focus of national memory. The study argues that personal memory predominated over political memory for a number of reasons, the most important being the relative unimportance of the nation of Vietnam to most Americans. -

A Long Walk Home: the Role of Class and the Military in the Springsteen Catalogue Michael S

A Long Walk Home: The Role of Class and the Military in the Springsteen Catalogue Michael S. Neiberg United States Army War College and Robert M. Citino National World War II Museum1 Abstract This article analyzes the themes of class and military service in the Springsteen canon. As a member of the baby boom generation who narrowly missed service in Vietnam, Springsteen’s reflection on these heretofore unappreciated themes should not be surprising. Springsteen’s emergence as a musician and American icon coincide with the end of conscription and the introduction of the All-Volunteer Force in 1973. He became an international superstar as Americans were debating the meaning of the post-Vietnam era and the patriotic resurgence of the Reagan era. Because of this context, Springsteen himself became involved in veterans issues and was a voice of protest against the 2003 Iraq War. In a well-known monologue from his Live 1975-85 box set (1986), Bruce Springsteen recalls arguing with his father Douglas about the younger Springsteen’s plans for his future. Whenever Bruce provided inadequate explanations for his life goals, Douglas responded that he could not wait for the Army to “make a man” out of his long-haired, seemingly aimless son. Springsteen 1 Copyright © Michael S. Neiberg and Robert M. Citino, 2016. Michael Neiberg would like to thank Derek Varble, with whom he saw Springsteen in concert in Denver in 2005, for his helpful comments on a draft of this article. Address correspondence to [email protected] or [email protected]. BOSS: The Biannual Online-Journal of Springsteen Studies 2.1 (2016) http://boss.mcgill.ca/ 42 NEIBERG AND CITINO describes his fear as he departed for an Army induction physical in 1968, at the height of domestic discord over the Vietnam War. -

Disability Studies Quarterly

disability ISSN 1041-5718 . studies ·Fall 1990 quarterly Volume 1O No. 4 Editor: Irving Kenneth Zola · Managing Editor: Janet Boudreau Co-editor for this. issue: Sandra Gordon, Senior Vice-President, Communications, National Easter Seal Society Issue Theme: The Media II Dear Reader, No DSQ has not shrunk. Ow new format allows us to print more mo.terial in a smaller space. Our updated computer facilities .will also pennit us to go to. direct billing for subscriptions. You will receive the first· request for 1991 in about a month. This issue returns to a favorite topic - the Media with a special section just devoted to reviews ofMy Left Foot and Born on the Powth ofJuly. Winter 1991 (deadline December 1, 1990) will as usual be a generic one. Spring 1991 (deadline March 1, 1991) will be devoted to Bioethics. Adrienne Asch, (316 W. 104th SL, Apt 3A, New York; NY 10025) will serve as Co-Editor Summer 1991 (deadline lune 1, i991) will emphasize Disability Policy- Past, Present and Fuiw-e. ATlll in the wings, depending as always on interest and further suggestions Aging II, General Issues of Technology and Psychosocial,· Models ofRehabilitation. The Editors much the same way it once gingerly introduced black faces." An Associated Press story, 11Advertisers Work_ to Hire the Handicapped,U publishedin th~ By Sandra Gordon, (Senior Vice CillCAGO TRIBUNE Oct. 29, 1989, cited a President, Corporate Communications, National number of television commercials in which Easter Seal Society). people with disabilities are cast. According to the A number of times during this past year article, "Advocates for .. -

1 Hl90ak Steven Biel Fall 2014 Friday 10-‐12 Barker 128 Office Hours

HL90ak Steven Biel Fall 2014 Friday 10-12 Barker 128 Office hours: By appointment [email protected] 617-495-4858 The Vietnam War in American Culture As we mark the 50th anniversary of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, this course will examine the U.S. war in Vietnam from the 1950s through the fall of Saigon, and its legacies up to the present. Considering a range of texts by and about soldiers and veterans, policy makers and protesters, reporters and refugees, the course covers key events in the war, as well as representations and reinterpretations of these events in later years. In each week, I have paired materials produced during the war with those produced after the war in order to explore Americans’ contested and changing understandings of the experiences and meanings of the Vietnam War. Texts include popular films, documentaries, journalism, fiction, letters, diaries, government documents, and war memorials. Course Requirements This is a seminar. Students are expected to come to class prepared for discussion about the materials assigned each week. In addition, students will write two papers and take a three- hour final exam. Class Participation 20% Paper One (5-7 pages) 20% Paper Two (8-10 pages) 30% Final Exam 30% Academic Integrity In this course, collaboration of any sort on any work submitted for formal evaluation is not permitted. This means that you may not discuss your paper assignments with other students. All work should be entirely your own and must use appropriate citation practices to acknowledge the use of books, articles, websites, lectures, discussions, etc., that you have consulted to complete your assignments. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

Writing and the Unknown Australian Soldier

Ffion Murphy TEXT Vol 22 No 1 Edith Cowan University Ffion Murphy Speaking for the dead: Writing and the Unknown Australian Soldier Abstract One third of the 60,000 Australians killed in the 1914-1918 war were unable to be identified. Known collectively as the ‘Unknown Soldier’ they were reburied in the postwar years with the inscription ‘Known unto God’. In 1993, the remains of one Australian killed on the Western Front were exhumed, repatriated and interred in the Hall of Memory at the Australian War Memorial. In 2007, Archie Weller published a poem titled the ‘Unknown Soldier’ (Weller 2007) which gives a name, voice, history and character to the soldier-larrikin and anti-hero whose bones lie there, effectively challenging former prime-minister Paul Keating’s eulogy which insists ‘We will never know who this Australian was’ (Keating 1993). Weller deploys prosopopoeia, which has been described as the ‘fiction of the voice-from-beyond-the-grave’ and a ‘master trope’ of poetic discourse. His verse undercuts notions of the sacred associated with the Unknown Soldier and creates presence from absence, making explicit a key motive of imaginative writing. This paper speculates on the potency of the ‘unknown’ and the way that texts like tombs assist concealment and revelation, remembering and forgetting, resurrection and erasure. Keywords: Unknown Australian Soldier, corpse poem, First World War Introduction “Like” and “like” and “like” – but what is the thing that lies beneath the semblance of the thing?… There is a square; there is an oblong. The players take the square and place it upon the oblong. -

Hennings, Thomas C., Jr. (1903-1960), Papers, 1901-1960 3000 190.5 Linear Feet, 6 Audio Tapes, 5 Films, 5 Rolls of Microfilm, 25 Records, 1 Oversize Volume

C Hennings, Thomas C., Jr. (1903-1960), Papers, 1901-1960 3000 190.5 linear feet, 6 audio tapes, 5 films, 5 rolls of microfilm, 25 records, 1 oversize volume MICROFILM (Volumes only) This collection is available at The State Historical Society of Missouri. If you would like more information, please contact us at [email protected]. INTRODUCTION Personal and political papers of a Democratic congressman, 1934-1940; St. Louis circuit attorney, 1940-1941; naval officer, 1941-1944; lawyer, 1944-1950; and U.S. senator, 1950-1960. Collection focuses on senatorial years, the bulk consisting of constituent correspondence, and is arranged topically. DONOR INFORMATION The Hennings Papers were donated to the University of Missouri by Mrs. Thomas C. Hennings, Jr. on 30 October 1960 (Accession No. 3465). BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Thomas C. Hennings, Jr., was born in St. Louis on 30 June 1903. He was educated in the St. Louis public schools, received his A.B. degree from Cornell University in 1924 and his LL.B. from Washington University in 1926. He was admitted to the Missouri Bar in 1926. Hennings was St. Louis assistant circuit attorney from 1929 to 1935, a U.S. congressman from 1934 to 1940, and St. Louis circuit attorney from 1940 to 1941. From 1941 to 1944 he was a naval officer. After the war he returned to St. Louis where he practiced law until he became U.S. Senator from 1950 to 1960. He died on 13 September 1960. SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE The Thomas C. Hennings Papers consist of his personal and political papers with the bulk focusing on his senatorial career and consisting mainly of constituent correspondence. -

1. There Are 58395 Names in Total on the Wall. That Includes All Dead

‘Fact Sheet’ - Revision 39B_May 2021 by Allen McCabe, in honor of WWII, Korea and Vietnam Vet & Volunteer Frank Bosch. If you see any errors email me at [email protected] By the numbers: 1. There are 58,395 names in total on The Wall. That includes all dead and missing, duplicates, corrected spellings, still alive when the Wall was dedicated, and a civilian. 2. There are 58,281 – dead and status unknown - on The Wall. This is the correct answer to a visitor asking how many we lost. This matches the DoD number. 3. The delta of 114 is due to corrected misspellings (69), duplicates (13), and a number of living who should not have been on The Wall (32). 69+13+32=114. 4. There are 732 ‘+’ symbols on The Wall. The ‘+’ symbol on The Wall does NOT mean ‘missing in action’. It was a designation for ‘status unknown’. A diamond is ‘dead’ and a ‘+’ is status unknown…no confirmation of death. There were 1,256 ‘+’ symbols on The Wall at dedication in 1982. 524 ‘+’ symbols have been changed to diamonds, including 3 in 2020. No status changes were made in 2021 – though 2 servicemen were found and indentified – they already had ‘diamonds’. 5. The DoD number for ‘Unaccounted for’ is 1,584 as of Spring 2021. This is 852 more than the number of ‘+’ symbols on the Wall. Someone could be ‘unaccounted for’ on the DoD list and have a diamond on The Wall. Michael Blassie is a good example – Panel 1E, Line 23…always had a diamond but was DoD ‘unaccounted for’.