SHORT STORIES by Tim Cloudsley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Humble Protest a Literary Generation's Quest for The

A HUMBLE PROTEST A LITERARY GENERATION’S QUEST FOR THE HEROIC SELF, 1917 – 1930 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jason A. Powell, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Steven Conn, Adviser Professor Paula Baker Professor David Steigerwald _____________________ Adviser Professor George Cotkin History Graduate Program Copyright by Jason Powell 2008 ABSTRACT Through the life and works of novelist John Dos Passos this project reexamines the inter-war cultural phenomenon that we call the Lost Generation. The Great War had destroyed traditional models of heroism for twenties intellectuals such as Ernest Hemingway, Edmund Wilson, Malcolm Cowley, E. E. Cummings, Hart Crane, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and John Dos Passos, compelling them to create a new understanding of what I call the “heroic self.” Through a modernist, experience based, epistemology these writers deemed that the relationship between the heroic individual and the world consisted of a dialectical tension between irony and romance. The ironic interpretation, the view that the world is an antagonistic force out to suppress individual vitality, drove these intellectuals to adopt the Freudian conception of heroism as a revolt against social oppression. The Lost Generation rebelled against these pernicious forces which they believed existed in the forms of militarism, patriotism, progressivism, and absolutism. The -

Food for Feeling Great Part 1

SPRING 2011 True $5.00 Natural Health The Magazine of the Natural Health Society of Australia Food for feeling great Part 1 - fresh fruits Safe breast screening Teen anger - why? Our amazing feet Bowen Therapy Veggie garden, Part 2 – spring planting Recipes - from Laos An unusual new study Editorial Imagine my surprise when a young naturo- product promoted in this magazine is first This issue initiates a series path phoned and said she is looking for vetted by us. Quite often, there is a fasci- of articles on the different “unvaccinated adults” to participate in a nating and passionate story behind how food categories, Part 1 covering study to investigate the health of people the proprietor became interested in the fresh fruits. We also continue the series who have never been vaccinated. What product in the first place. In this issue, we on veggie gardening with Part 2. a great idea! Come to think of it, this is present two such stories. Vegetarian restaurants are not only found something that the medical authorities Joe Ciancio markets an air purifier-ioniser in Sydney! We branch out to Adelaide in should have done long. (which keeps the pollutants within itself), this issue, and will present restaurants in Because vaccination has become a because he had discovered – almost to other states in future issues. In fact, our sacred cow in Australia, it is very difficult his peril – the dangers of polluted air and readers may be able to make some rec- to obtain objective information about water. His eye-opening story is on page 14. -

Under Postcolonial Eyes

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters University of Nebraska Press 2013 Under Postcolonial Eyes Efraim Sicher Linda Weinhouse Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/unpresssamples Sicher, Efraim and Weinhouse, Linda, "Under Postcolonial Eyes" (2013). University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters. 138. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/unpresssamples/138 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Nebraska Press at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Under Postcolonial Eyes: Figuring the “jew” in Contemporary British Writing Buy the Book STUDIES IN ANTISEMITISM Vadim Rossman, Russian Intellectual Antisemitism in the Post-Communist Era Anthony D. Kauders, Democratization and the Jews, Munich 1945–1965 Cesare G. DeMichelis, The Non-Existent Manuscript: A Study of the Protocols of the Sages of Zion Robert S. Wistrich, Laboratory for World Destruction: Germans and Jews in Central Europe Graciela Ben-Dror, The Catholic Church and the Jews, Argentina, 1933– 1945 Andrei Oi܈teanu, Inventing the Jew: Antisemitic Stereotypes in Romanian and Other Central-East European Cultures Olaf Blaschke, Offenders or Victims? German Jews and the Causes of Modern Catholic Antisemitism Robert S. Wistrich, -

Adult-Catalogue-Jul-Dec-2020 Web.Pdf

Spine: 7.3mm July – December 2020 4 Original Fiction 14 Raven Books – Crime, Thriller & Mystery 20 Original Non-Fiction 46 Cookery 54 Paperback Fiction 60 Paperback Non-Fiction 74 Bloomsbury Business 78 Sigma – Popular Science 82 Green Tree – Wellbeing 86 Bloomsbury Sport & Wisden 94 Yearbooks 98 Bloomsbury Contact List & International Sales 101 Social Media Contacts 102 Index export information TPB Trade Paperback PAPERBACK B format paperback (dimensions 198 mm x 129 mm) ORIGINAL FICTION 4 ORIGINAL FICTION Why Visit America Matthew Baker A twisted, exhilarating and darkly strange vision of our time, explored in thirteen interconnected episodes young man breaks the news to his family that he is going to A transition from an analogue body to a digital existence. A man returns home after committing a great crime, his sentence being that his memory, and thereby his entire life, is wiped clean. The citizens of Plainfield, Texas, have had it with the United States. So they decide to secede, rename themselves America in memory of their former country, and set themselves up to receive tourists from their closest neighbour: America. The stories in Matthew Baker’s collection portray a world within touching distance of our own. This is an America riven by dilemmas confronting so many of us – from old age to consumerism, drugs to internet culture – turned on its head by one of the most darkly innovative and defiantly strange voices of the moment. 04 AUGUST 2020 IMPRINT: BLOOMSBURY PUBLISHING Matthew Baker is the author of the story collection Hybrid EXPORT TPB / 9781526618399 / £13.99 Creatures. His stories have appeared in the Paris Review, American HARDBACK / 9781526618382 / £14.99 EBOOK / 9781526618405 / £12.58 Short Fiction, New England Review, One Story, Electric Literature TERRITORY: COMMONWEALTH (EXCLUDING CANADA)/ and Conjunctions, and in anthologies including Best of the Net UK/OPEN MARKET and Best Small Fictions. -

The Jew: Between Victimhood and Complicity, Or How an Army-Dodger and Rootless Cosmopolitan Has Become a Saintly Ogre

Chapter 4 The Jew: Between Victimhood and Complicity, or How an Army-Dodger and Rootless Cosmopolitan Has Become a Saintly Ogre There has never been and there is no anti-Semitism in the Soviet Union. Alexander Kosygin1 ∵ Introduction It is hardly possible to write about the 1941–1945 conflict between Stalin’s Russia and Hitler’s Germany without mentioning the Jewish experience in a war that, as Kiril Feferman claims, was ‘the Jews’ war’, the Nazis’ principal enemy being Judeo-Bolshevism.2 Indeed, when Germany invaded the USSR in June 1941 Soviet Russia boasted the largest Jewish diaspora in Europe3 and, as in other countries conquered by Hitler’s army, in the German-occupied parts of the USSR Jews became the prime target of Nazi violence. Having been rounded up into ghettos, they were either shot after digging their own graves or, less frequently, transported to concentration or extermination camps. Jews were also the victims of the worst genocide that the Germans carried out on Soviet soil: in September 1941 at Babi Yar, a huge wooded ravine on the out- skirts of Kiev, over thirty-three thousand men, women and children were killed within two days. Yet, in the Soviet context, Jewish wartime history goes beyond the Holocaust, as some half a million Jews fought in both the Red Army and 1 Chairman of the Soviet Council of Ministers 1964–1980. 2 Kiril Feferman, ‘ “The Jews’ War”: Attitudes of Soviet Jewish Soldiers and Officers towards the USSR in 1940–41’, Journal of Slavic Military Studies, 27.4 (2014), 574–90 (p. -

Corus Entertainment New and Returning Specialty Series 2020-2021

CORUS ENTERTAINMENT NEW AND RETURNING SPECIALTY SERIES 2020-2021 LIFESTYLE Food Network Canada Bakeaway Camp with Martha Stewart (4x60) – NEW SERIES – (Fall 2020) Six talented home baker campers brave the outdoor elements for a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to perfect their skills under the watchful eye of host Jesse Palmer, baking mentor Martha Stewart and her camp counselors, baking experts Carla Hall and Dan Langan. Equal parts baking boot camp and camp- inspired games and challenges, the bakers compete in two rounds, with the most-impressive baker of the first heat getting a one-on-one mentoring session with Martha in her home kitchen. The baker that displays the least amount of progress will pack their bags and head home, and the last camper standing wins a bake-tacular kitchen filled with appliances worth $25,000! Beat Bobby Flay (27x30) – NEW EPISODES – (Fall 2020) On Beat Bobby Flay skilled chefs compete for the opportunity to cook against culinary master Bobby. The action starts with two talented cooks going head to head in a culinary battle, and the winner proceeds to round two for the ultimate food face off against the famed chef. Big Food Bucket List, Season 2 (26x30) – NEW SEASON – (Corus Studios/Lone Eagle Entertainment) (Fall 2020, Winter 2021) In season 2 of Big Food Bucket List, Host John Catucci (You Gotta Eat Here!) is back to take viewers on a brand-new food adventure across North America as he checks buzz-worthy, crazy, delicious food off his bucket list. In each episode, John visits the restaurants behind these must-eat meals and hits the kitchen to learn how the chefs make their mind-blowing creations. -

Develo Tries to Brin Reta Bac to Broad

ROETareRA. = Scho Memoria Danc The School Noteboo Honor Joh Pitrellj Pag 12 By Jim McCrann Hig School Writer “One da we tried to cut out from school. We were half down way to Calda Pizza wh en about 20 kids came Tunning out shoutin “Pitrelli’s in there! Run!” I was wearing Hicksville my jacket and Mr. Pitrellj ‘yelled ‘Yo! Hicksville! Tarn Incorporatin The Hicksville around! Get back to school Edition of the now! I want Mid-Island Herald you in my office—now!’ Mr. Pitrelli ILLUSTRATED got into his car and he was smokin NEWS his pipeandhe pulled rh overnext tous and said, Vol. ‘Get back to clas 3 No. 36 Hicksville, N.Y. and and we& © forge about Thursday, February 16 1989 1989 Anton the 35¢ per copy Communit Newspapers of Lon island whol thing’ It was the All Rights Reserved. funniest thing.” Central Office Phone: 747-8282 This Hicks High School student and many others hav stories to tell abou the late Jo Pitrelli,an Tries to administrative assistant who Develo Brin Reta Bac to Passed away last August. Although a Broad disciplinaria Mr. Pitrelli was respected Rita his by By Langdon students. If a request b a real estate Hicksville students held develop is a danc in his approved by the town board, memory residents may last Thursda It was an event to soon be able to sho on as “honor aman Broadwa the who somehow touched all once did of before the state widened the road us,” accordi to student bod almost president, 1 years ago. -

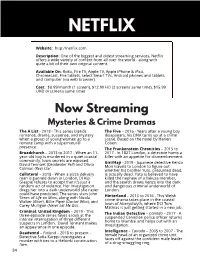

British TV Streaming Guide

NETFLIX Website: http://netflix.com Description: One of the biggest and oldest streaming services, Netflix offers a wide variety of content from all over the world - along with quite a bit of their own original content. Available On: Roku, Fire TV, Apple TV, Apple iPhone & iPad, Chromecast, Fire tablets, select Smart TVs, Android phones and tablets, and computer (via web browser). Cost: $8.99/month (1 screen), $12.99 HD (2 screens same time), $15.99 UHD (4 screens same time) Now Streaming Mysteries & Crime Dramas The A List - 2018 - This series blends The Five – 2016 - Years after a young boy romance, drama, suspense, and mystery disappears, his DNA turns up at a crime when a group of young women go to a scene. Based on the novel by Harlen remote camp with a supernatural Coben. presence. The Frankenstein Chronicles – 2015 to Broadchurch – 2013 to 2017 - When an 11- 2017 - In 1827 London, a detective hunts a year-old boy is murdered in a quiet coastal killer with an appetite for dismemberment. community, town secrets are exposed. Giri/Haji - 2019 - Japanese detective Kenzo David Tennant (Deadwater Fell) and Olivia Mori travels to London to figure out Colman (Rev) star. whether his brother Yuto, presumed dead, Collateral – 2018 - When a pizza delivery is actually dead. Yuto is believed to have man is gunned down in London, DI Kip killed the nephew of a Yakuza member, Glaspie refuses to accept that it's just a and the search draws Kenzo into the dark random act of violence. Her investigation and dangerous criminal underworld of drags her into a dark underworld she never London. -

“Mr. Nobody from Nowhere”: Ethnocentric Nationalism, Cultural Cosmopolitanism, and the Reinvention of Personal Identity in F

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Spring 2018 “Mr. Nobody from Nowhere”: Ethnocentric Nationalism, Cultural Cosmopolitanism, and the Reinvention of Personal Identity in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby and Mohsin Hamid’s The Reluctant Fundamentalist Hana Mohammed Smail Missouri State University, [email protected] As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Smail, Hana Mohammed, "“Mr. Nobody from Nowhere”: Ethnocentric Nationalism, Cultural Cosmopolitanism, and the Reinvention of Personal Identity in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby and Mohsin Hamid’s The Reluctant Fundamentalist" (2018). MSU Graduate Theses. 3265. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/3265 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “MR. NOBODY FROM NOWHERE”: ETHNOCENTRIC NATIONALISM, CULTURAL COSMOPOLITANISM, AND THE REINVENTION OF PERSONAL IDENTITY IN F. SCOTT FITZGERALD’S THE GREAT GATSBY AND MOHSIN HAMID’S THE RELUCTANT FUNDAMENTALIST A Master’s Thesis Presented to The Graduate College of Missouri State University In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts, English By Hana Mohammed Smail May 2018 Copyright 2018 by Hana Mohammed Smail ii “MR. -

PWCF News the Newsletter of Prader-Willi California Foundation an Affiliate Of

PWCF News The Newsletter of Prader-Willi California Foundation An Affiliate of April-June, 2010 ~ Volume 20, Number 2 Prader-Willi Syndrome Benefit Concert Craneway Pavilion—Billy Hustace Photography Get your groove on while you raise awareness of Prader-Willi syndrome and funds for PWCF. Make it a Date Night! Come out to the extraordinary Craneway Pavilion, enjoy a delicious dinner at the Boilerhouse Restaurant and a fantastically fun evening of rock ‘n roll! Tell your neighbors, invite your friends! Ticket sales benefit Prader-Willi California Foundation. For more information contact PWCF 310-372-5053 or 800-400-9994 within California. Sandi & The RockerFellers Friday, July 16, 2010 at 8:00 p.m. Sandi Snyder - Lead Vocals Craneway Pavilion Skip Snyder - Lead Guitar & Vocals 1414 Harbour Way S Ken Fisher - Bass Guitar Richmond, CA 94804 Art Beringer - Drums Tickets are $5 at the door Enjoy rock, blues and jazz influences from '70s Ten minutes from Berkeley through today including songs played by bands such as The Pretenders, Sheryl Crow, Bonnie Raitt, Five minutes from Richmond/San Rafael Bridge Lynyrd Skynyrd, Train, No Doubt, Huey Lewis and Fifteen minutes from San Francisco Bay Bridge Craneway.com // CranewayBlog.com many others. Boilerhouse Restaurant 510.215.6000 In This Issue: Parent to Parent on Sex Education 3 Call for Board Candidates 11 Growth Hormone: Long Term Safety 6 Experience with Depo-Provera 13 In The Trenches Part I 7 Marriage & Family Part II 15 Walking for PWS Events 8 Ride The Wave 18 PRADER-WILLI PWS Support Contacts -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Beyond the nation : American expatriate writers and the process of cosmopolitanism Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2bb925ff Author Weik, Alexa Publication Date 2008 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Beyond the Nation: American Expatriate Writers and the Process of Cosmopolitanism A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Literature by Alexa Weik Committee in charge: Professor Michael Davidson, Chair Professor Frank Biess Professor Marcel Hénaff Professor Lisa Lowe Professor Don Wayne 2008 © Alexa Weik, 2008 All rights reserved The Dissertation of Alexa Weik is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm: _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2008 iii To my mother Barbara, for her everlasting love and support. iv “Life has suddenly changed. The confines of a community are no longer a single town, or even a single nation. The community has suddenly become the whole world, and world problems impinge upon the humblest of us.” – Pearl S. Buck v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page……………………………………………………………… iii Dedication………………………………………………………………….. iv Epigraph……………………………………………………………………. -

The Gothic Demonization of the Jew Diane Hoeveler Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette English Faculty Research and Publications English, Department of 1-1-2005 Charlotte Dacre’s Zofloya: The Gothic Demonization of the Jew Diane Hoeveler Marquette University, [email protected] Accepted version. "Charlotte Dacre’s Zofloya: The Gothic eD monization of the Jew," in The Jews and British Romanticism: Politics, Religion, Culture. Ed. Sheila A. Spector. New York: Palgrave-Macmillan, 2005: 165-178. DOI. © 2005 Palgrave-Macmillan Publishing. Used with permission. CHAPTER CHARLOTTE DACRE’S ZOFLOYA: THE GOTHIC DEMONIZATION OF THE JEW Diane Long Hoeveler I In 1769, an odd little chapbook made its appearance in Hull, entitled The Wandering Jew, or, The Shoemaker of Jerusalem: Who Lived When Our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ Was Crucified, and By Him Appointed to Wander Until He Comes Again: With His Discourse With Some Clergymen About the End of the World.i This anonymous pamphlet was typical of much millenarian propaganda floating around at the time. But in this work, the Wandering Jew informs the Protestant clergymen that “before the End of the World the Jews shall be gathered together from all Parts of the World, and returned to Jerusalem, and live there, and it shall flourish as much as ever, and that they, and all others, shall become Christians, and that Wars shall cease, and the whole World live in Unity with one another” (7-8). The need to believe that the Other, the Jew, would become “one of us” was indeed strong across Europe, and the thinking was that if they could not be converted, then they could always be killed – for their own good, of course.