Scaling the Sublime: Art at the Limits of Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To the Ends of the Earth: Art and Environment | Tate

Research Online research publications RESEARCH PAPER To the Ends of the Earth: Art and Environment Art & Environment By Nicholas Alfrey, Stephen Daniels, Joy Sleeman 11 May 2012 Introducing the group of articles devoted to the theme of ‘Art & Environment’ in issue 17 of Tate Papers, this essay reflects on changing perceptions of the term ‘environment’ in relation to artistic practices and describes the context for a series of case studies of sites, spaces and processes that extend from the immediate locality to the most remote boundaries of knowledge and experience. The group of articles devoted to the theme of art and environment in issue 17 of Tate Papers aims to explore new research frontiers between visual art and the material environment. The papers arise from a conference held at Tate Britain in June 2010 at which a range of practitioners and scholars – artists, writers, curators, theorists, historians and geographers – presented case studies of artworks addressing specific sites, spaces, places and landscapes in a variety of media, including film, photography, painting, sculpture and installation. The conference considered relations between artistic approaches to the environment and other forms of knowledge and practice, including scientific knowledge and social activism. The papers addressed cultural questions of weather and climate, ruin and waste, dwelling and movement, boundary and journey, and reflected on the way the environment is experienced and imagined and on the place of art in the material world. Held at a time when the emergent effects of economic crisis were intersecting with a more established sense of ecological crisis, the conference offered an opportunity to rethink the relations between art and environment, which had become central to a number of art exhibitions and publications. -

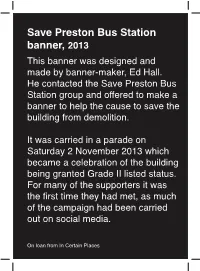

Save Preston Bus Station Banner

6DYH3UHVWRQ%XV6WDWLRQ EDQQHU 7KLVEDQQHUZDVGHVLJQHGDQG PDGHE\EDQQHUPDNHU(G+DOO +HFRQWDFWHGWKH6DYH3UHVWRQ%XV 6WDWLRQJURXSDQGRIIHUHGWRPDNHD EDQQHUWRKHOSWKHFDXVHWRVDYHWKH EXLOGLQJIURPGHPROLWLRQ ,WZDVFDUULHGLQDSDUDGHRQ 6DWXUGD\1RYHPEHUZKLFK EHFDPHDFHOHEUDWLRQRIWKHEXLOGLQJ EHLQJJUDQWHG*UDGH,,OLVWHGVWDWXV )RUPDQ\RIWKHVXSSRUWHUVLWZDV WKHÀUVWWLPHWKH\KDGPHWDVPXFK RIWKHFDPSDLJQKDGEHHQFDUULHG RXWRQVRFLDOPHGLD 2QORDQIURP,Q&HUWDLQ3ODFHV %XV6WDWLRQ&RQQHFWLRQV 7KHVHFDVHVFRQWDLQLWHPVEURXJKW LQE\SHRSOHZKRUHVSRQGHGWRD FDOORXWIRUREMHFWVWKDWFRQQHFWWKHP WR3UHVWRQ%XV6WDWLRQ 7KH\RIIHUDJOLPSVHLQWRZKDWWKH EXLOGLQJKDVPHDQWWRWKHSHRSOHRI 3UHVWRQDQGIXUWKHUDÀHOGRYHUWKH ODVW\HDUV 6DUDK:DONHU 7KLVSKRWRJUDSKZDVWDNHQE\ 6DUDKҋVGDXJKWHU(PPDLQ 6KHLVQRZVWXG\LQJDUFKLWHFWXUDO GHVLJQDW/LYHUSRRO8QLYHUVLW\ 1RUPDQ3D\QH 1RUPDQ3D\QHXVHGWKLV1DWLRQDO ([SUHVVGLVFRXQWFDUGLQWKHV ZKHQKHZDVDVWXGHQWDW8&/DQ DQGWUDYHOOHGIURP3UHVWRQ%XV 6WDWLRQWR6RXWKDPSWRQ +HOHQ/LQGVD\ 7KLVFROOHFWLRQRILWHPVUHÁHFWV +HOHQҋVORQJLQWHUHVWLQ3UHVWRQ%XV 6WDWLRQ7KHFRQFUHWHIUDJPHQWDQG &KULVWPDVFDUGZHUHIURP FROOHDJXHVDW/DQFDVKLUH3RVW6KH DOVRKDVDSDUWLQWKHÀOP &KDUOHV4XLFN 7KHSRVWFDUGZDVDSUHVHQW,WLV DOZD\VNHSWLQWKHEDFNRIKLV QRWHERRNDQGLVFDUULHGDWDOOWLPHV DVUHIHUHQFH 0U/HDYHU :DVDNHHQEXVVSRWWHU7KLV EXVVSRWWLQJPDQXDOGDWHVIURPWKH VDQGPDQ\RIWKHEXVHVLQLW XVHG3UHVWRQ%XV6WDWLRQ 5LWD:KLWORFN 7KLVPXJDQGFRDVWHUXVHGWREH VROGLQ3UHVWRQ7RXULVW,QIRUPDWLRQ &HQWUHZKHUH5LWDZDV0DQDJHU 6KHSXUFKDVHGWKHPDVVKHORYHV %UXWDOLVWDUFKLWHFWXUH &KULV/RQHUJDQ &KULVLVD6HQLRU(QJLQHHUDW$583 LQ0DQFKHVWHU$OORIWKHVWDIILQWKH RIÀFHKDYHDFXEHZLWKWKHLUSLFWXUH RQ,WDOVRLQFOXGHVVRPHWKLQJ -

Damien Hirst E Il Mercato Dell'arte Contemporanea: La Carriera Di Un Young British Artist

Corso di Laurea magistrale (ordinamento ex D.M. 270/2004) in Economia e Gestione delle Arti e delle attività culturali Tesi di Laurea DAMIEN HIRST E IL MERCATO DELL'ARTE CONTEMPORANEA: LA CARRIERA DI UN YOUNG BRITISH ARTIST Relatore Prof. Stefania Portinari Laureanda Martina Pellizzer Matricola 816581 Anno Accademico 2012 / 2013 1 INDICE INTRODUZIONE p. 3 CAPITOLO 1 ALCUNE RIFLESSIONI SUL MERCATO DELL'ARTE CONTEMPORANEA: ISTITUZIONI E STRUTTURE DI PROMOZIONE E VENDITA 1 L'Evoluzione del sistema delle gallerie e della figura del gallerista p. 3 2. Il ruolo dei musei p. 19 3 Il ruolo dei collezionisti p. 28 4 Le case d'asta p. 36 CAPITOLO 2 DAMIEN HIRST: DA A THOUSAND YEARS (1990) A FOR THE LOVE OF GOD (2007) 1 Il sistema dell'arte inglese negli anni Novanta: gli Young British Artist …........p. 41 2 Damien Hirst una carriera in ascesa, da “Frezze” alla retrospettiva presso la Tate Modern p. 47 3 I galleristi di Damien Hirst p. 67 CAPITOLO 3 IL RUOLO DEL MERCATO DELL'ARTE NELLA CARRIERA DI DAMIEN HIRST 1 L'asta di Sotheby's: “Beautiful inside my head forever” p. 78 2 Rapporto tra esposizione e valore delle opere dal 2009 al 2012..............................p. 97 CONCLUSIONI p. 117 APPENDICE p. 120 BIBLIOGRAFIA p. 137 2 INTRODUZIONE Questa tesi di laurea magistrale si pone come obiettivo di analizzare la carriera dell'artista inglese Damien Hirst mettendo in evidenza il ruolo che il mercato dell'arte ha avuto nella sua carriera. Il primo capitolo, dal titolo “Alcuni riflessioni sul mercato dell'arte contemporanea”, propone una breve disanima sul funzionamento del mercato dell'arte contemporanea, analizzando in particolar modo il ruolo di collezionisti, galleristi, istituzioni museali e case d'asta, tutti soggetti in grado di influenzare notevolmente la carriera di un artista, anche se in maniera differente. -

Collaborative Relationshipsaid & Abet

news venice biennale, international relations features artists and curators talking: issues and outcomes, arts funding: canadian comparison, open studios, postgraduate focus debate believe in film JUNE 2011 collaborative relationships aid & abet £5.95/ 8.55 11 MAY–26 JUN 13 JUL–28 AUG 7 MAY– 26 JUN JVA at Jerwood Space, JVA at Jerwood Space, JVA on tour London London DLI Museum & Art Gallery, Durham An exhibition of new works by Selected artists Farah the inaugural Jerwood Painting Bandookwala, Emmanuel Final chance to see the 2010 Fellows; Clare Mitten, Cara Boos, Heike Brachlow exhibition selected by Charles Nahaul and Corinna Till. and Keith Harrison exhibit Darwent, Jenni Lomax and newly commissioned work. Emma Talbot. Curated by mentors; Paul Bonaventura, The 2011 selectors are durham.gov.uk/dli Stephen Farthing RA Emmanuel Cooper, Siobhan Twitter: #JDP2010 and Chantal Joffe. Davis and Jonathan Watkins. jerwoodvisualarts.org jerwoodvisualarts.org CALL FOR ENTRIES 2011 Twitter: #JPF2011 Twitter: #JMO2011 Deadline: Mon 20 June at 5pm The 2011 selectors are Iwona Blazwick, Tim Marlow and Rachel Whiteread. Apply online at jerwoodvisualarts.org Twitter: #JDP2011 Artist Associates: Beyond The Commission Saturday 16 July 2011, 10.30am – 4pm The Arts University College at Bournemouth | £30 / £20 concessions Artist Associates: Beyond the Commission focuses on the practice of supporting artists within the contemporary visual arts beyond the traditional curatorial, exhibition and commissioning role of the public sector, including this mentoring, advice, advocacy, and training. Confirmed Speakers: Simon Faithfull, (Artist and ArtSway Associate) Alistair Gentry (Artist and Writer, Market Project) Donna Lynas (Director, Wysing Arts Centre) Dida Tait (Head of Membership & Market Development, Contemporary Art Society) Chaired by Mark Segal (Director, ArtSway). -

Ne W Forest Pavilion 52Nd International Art Exhibition La Bi Ennale Di Venezia

NE W FOREST PAVILION 52ND INTERNATIONAL ART EXHIBITION LA BI ENNALE DI VENEZIA ESSAYS MARTIN COOMER on SIMON FAITHFULL ANNA-CATHARINA GEBBERS on BEATE GÜTSCHOW JOHN SLYCE on ANNE HARDY COLM LALLY & CECILIA WEE on IGLOO DAVID THORP on MELANIE MANCHOT CHARLOTTE FROST on STANZA New Forest Pavilion published by ArtSway and The Arts Institute at Bournemouth on the occasion of the exhibitions: NEW FOREST PAVILION 52nd International Art Exhibition - la Biennale di Venezia Palazzo Zenobio 10 June - 1 July 2007 and NEW FOREST PAVILION - LOCAL ArtSway 26 May - 15 July 2007 ArtSway, Station Road, Sway, Hampshire, SO41 6BA The Arts Institute at Bournemouth, Wallisdown, Poole, Dorset, BH12 5HH Editors: Peter Bonnell, Laura McLean-Ferris and Josepha Sanna English Translation from German: R. Jay Magill & Tanja Maka (text by Anna-Catharina Gebbers) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holders. Set in Nilland and Soho. Printed by Printwise, Lymington, England © the artists and the authors ISBN: 0-9543930-9-0 [ArtSway] ISBN: 978-0-901196-20-0 [The Arts Institute at Bournemouth] Introduction New Forest Pavilion is an ArtSway international project that presents the work of six artists to a global audience within the framework of ArtSway’s innovative artist support scheme and residency programme. Five of the exhibiting artists are former ArtSway artists-in-residence, with Stanza being curated by SCAN (Southern Collaborative Arts Network). The overarching theme that unites all six within the context of New Forest Pavilion is their treatment of how one experiences transformation, modi!cation and change. -

A Brief History of the Arts Catalyst

A Brief History of The Arts Catalyst 1 Introduction This small publication marks the 20th anniversary year of The Arts Catalyst. It celebrates some of the 120 artists’ projects that we have commissioned over those two decades. Based in London, The Arts Catalyst is one of Our new commissions, exhibitions the UK’s most distinctive arts organisations, and events in 2013 attracted over distinguished by ambitious artists’ projects that engage with the ideas and impact of science. We 57,000 UK visitors. are acknowledged internationally as a pioneer in this field and a leader in experimental art, known In 2013 our previous commissions for our curatorial flair, scale of ambition, and were internationally presented to a critical acuity. For most of our 20 years, the reach of around 30,000 people. programme has been curated and produced by the (founding) director with curator Rob La Frenais, We have facilitated projects and producer Gillean Dickie, and The Arts Catalyst staff presented our commissions in 27 team and associates. countries and all continents, including at major art events such as Our primary focus is new artists’ commissions, Venice Biennale and dOCUMEntA. presented as exhibitions, events and participatory projects, that are accessible, stimulating and artistically relevant. We aim to produce provocative, Our projects receive widespread playful, risk-taking projects that spark dynamic national and international media conversations about our changing world. This is coverage, reaching millions of people. underpinned by research and dialogue between In the last year we had features in The artists and world-class scientists and researchers. Guardian, The Times, Financial Times, Time Out, Wall Street Journal, Wired, The Arts Catalyst has a deep commitment to artists New Scientist, Art Monthly, Blueprint, and artistic process. -

O Último Ato Reflexões Sobre Performance, Morte, Violência E Transcendência

Bárbara de Oliveira Ahouagi O último ato Reflexões sobre performance, morte, violência e transcendência Belo Horizonte 2015 Bárbara de Oliveira Ahouagi O último ato Reflexões sobre performance, morte, violência e transcendência Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Artes da Escola de Belas Artes da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais como requesito à obtenção do título de Mestre em Artes. Área de Concentração: Arte e Tecnologia da Imagem Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Maria Angelica Melendi Belo Horizonte 2015 Ahouagi, Bárbara, 1980- O último ato [manuscrito] : reflexões sobre performance, morte, violência e transcendência / Bárbara de Oliveira Ahouagi. – 2015. 151 f. : il. + 3 folhas, em bolso. Orientadora: Maria Angelica Melendi Dissertação (mestrado) – Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Escola de Belas Artes, 2014. 1. Warburg, Aby, 1866-1929 – Atlas Mnemosyne – Teses . 2. Percepção visual – Teses. 3. Performance (Arte) – Teses. 4. Arte – Filosofia – Teses. 5. Arte moderna – 1960-1970 – Teses. I. Biasizzo, Maria Angélica Melendi, 1945- II. Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. Escola de Belas Artes. III. Título. CDD 701.15 Para Eliana e Michel. Para Paulo, Salomé, Ana Emília e Letícia Agradeço à Krsna, a fonte de tudo, e ao meu mestre espiritual, que me conecta à Ele. Agradecimentos sem fim à Piti, pela inspiração, cuida- do, amizade, dedicação, competência e liberdade. Agradeço à banca, todos meus professores. À Con- suelo, pela preciosa revisão. Aos colegas do grupo de pesquisa e meus amigos que contribuiram com esta pesquisa. Agradeço aos meus pais e antepassados e a todos os meus amigos que passaram ou que permanecem, me ensinando e me inspirando todos os dias. -

Tate Papers - the 'Comic Sublime': Eileen Agar at Ploumanac'h

Tate Papers - The 'Comic Sublime': Eileen Agar at Ploumanac'h http://www.tate.org.uk/research/tateresearch/tatepapers/05autumn/walke... ISSN 1753-9854 TATE’S ONLINE RESEARCH JOURNAL The 'Comic Sublime': Eileen Agar at Ploumanac'h Ian Walker Fig.1 Eileen Agar 'Rockface', Ploumanach 1936 Black and white photograph reproduced from original negative Tate Archive Photographic Collection 5.4.3 © Tate Archive 2005 On Saturday 4 July 1936, the International Surrealist Exhibition in London came to an end. In that same month, the Architectural Review magazine announced a competition. In April, they had published Paul Nash's article 'Swanage or Seaside Surrealism'.1 Now, in July, the magazine offered a prize for readers who sent in their own surrealist holiday photographs – 'spontaneous examples of surrealism discerned in English holiday resorts'. The judges would be Nash and Roland Penrose .2 At face value, this could be taken as a demonstration of the irredeemable frivolity of surrealism in England (it is difficult to imagine a surrealist snapshot competition in Paris judged by André Breton and Max Ernst ). But in a more positive light, it exemplifies rather well the interest that the English had in popular culture and in pleasure. Holidays were very important in English surrealism and some of its most interesting work was made during them. This essay will examine closely one particular set of photographs made by Eileen Agar in that month of July 1936 which illustrate this relationship between surrealism in England and pleasure. Eileen Agar had been one of the English stars of the surrealism exhibition, even though she had apparently not thought of herself as a 'surrealist' until the organizers of the show – Roland Penrose and Herbert Read – came to her studio and declared her to be one. -

Art & Environment

Art & Environment AHRC Landscape and Environment Conference 25-26 June 2010 at Tate Britain Image on cover: Straw bales in field from Robinson in Ruins © Patrick Keiller Image on this page: David Nash—Black Steps 2010 Photo Jonty Wilde Welcome … Welcome to Art & Environment. This is the third and final summer conference of the AHRC Landscape and Environment programme, following those on Landscape in Theory (Nottingham 2008) and Living Landscapes: Performance, Landscape and Environment (Aberystwyth, 2009). Like its forerunners Art and Environment focuses on a key theme of the programme and brings together project holders with fellow scholars and practitioners. The panels of this conference are made up of a range of Art & Environment experts in the field: artists, working in a range of AHRC Landscape and Environment Conference media, curators, authors, and academic researchers, including art historians and cultural geographers. Many presenters have multiple identities and affiliations. We are delighted Art and Environment is hosted by Tate Britain, who are a major award holder in the Landscape and Environment programme with a project on ‘The Sublime Object: Nature, Art and Language’. We are pleased you have accepted the invitation to come to the conference, hope you enjoy the proceedings and have the opportunity to contribute in discussion, from the floor or during lunch and the reception. Stephen Daniels Programme Director www.landscape.ac.uk This conference will explore engagements between visual art and the material environment. The environments in question are natural and fabricated, interior and exterior, urban and rural, terrestrial and aerial. The visual arts in question are historical and contemporary and in a range of media. -

This Book Is a Compendium of New Wave Posters. It Is Organized Around the Designers (At Last!)

“This book is a compendium of new wave posters. It is organized around the designers (at last!). It emphasizes the key contribution of Eastern Europe as well as Western Europe, and beyond. And it is a very timely volume, assembled with R|A|P’s usual flair, style and understanding.” –CHRISTOPHER FRAYLING, FROM THE INTRODUCTION 2 artbook.com French New Wave A Revolution in Design Edited by Tony Nourmand. Introduction by Christopher Frayling. The French New Wave of the 1950s and 1960s is one of the most important movements in the history of film. Its fresh energy and vision changed the cinematic landscape, and its style has had a seminal impact on pop culture. The poster artists tasked with selling these Nouvelle Vague films to the masses—in France and internationally—helped to create this style, and in so doing found themselves at the forefront of a revolution in art, graphic design and photography. French New Wave: A Revolution in Design celebrates explosive and groundbreaking poster art that accompanied French New Wave films like The 400 Blows (1959), Jules and Jim (1962) and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964). Featuring posters from over 20 countries, the imagery is accompanied by biographies on more than 100 artists, photographers and designers involved—the first time many of those responsible for promoting and portraying this movement have been properly recognized. This publication spotlights the poster designers who worked alongside directors, cinematographers and actors to define the look of the French New Wave. Artists presented in this volume include Jean-Michel Folon, Boris Grinsson, Waldemar Świerzy, Christian Broutin, Tomasz Rumiński, Hans Hillman, Georges Allard, René Ferracci, Bruno Rehak, Zdeněk Ziegler, Miroslav Vystrcil, Peter Strausfeld, Maciej Hibner, Andrzej Krajewski, Maciej Zbikowski, Josef Vylet’al, Sandro Simeoni, Averardo Ciriello, Marcello Colizzi and many more. -

The Recurring Desire to Experience by Zakriya Rabani a Non-Thesis

The Recurring Desire To Experience By Zakriya Rabani A non-thesis project in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts School of Art and Art History College of the Arts University of South Florida Major Professor: Cesar Cornejo, PHD Committee Member: Wendy Babcox, MFA Committee Member: Gregory Green, MFA Date of Approval: 04/11/2018 Keywords: installation, skateboards, mediated motion, soul, essence, used materials, imagination, potential, experience ⓒ Copyright 2018, Zakriya Rabani This paper reflects my worldview. I am not an expert on theory, people, life, sport, or even art, I can however speak about the concept of experience in my own life. Experience teaches us how to live, how to fail and succeed, but most importantly how to be what it is we desire. From a young age, my desire was to be great at everything, I felt I could achieve anything if I tried hard enough. I believe that this sense of desire is a recurring feeling throughout our lives, no matter the task, sport or occupancy. What is seen, felt and can be interpreted is shaped by experience, this is something I have realized through my upbringing and education. It is our participation with objects, environments and people that allow us to retain information. How we participate is unique to each individual, causing different actions and ideas to occur. Through “ ‘seeing yourself sensing’, a moment of perception, when the viewer pauses to consider what they are experiencing” and mediated motion1 where “viewers become more conscious of the act of movement through space.” I want participants to see what I see in the world. -

Art and Design (Short Course) Unit 2: Externally Set Assignment in Art and Design

Edexcel GCSE Art and Design (Short Course) Unit 2: Externally Set Assignment in Art and Design June 2010 – Examination Paper Reference Preparatory period: Approximately 20 hours Sustained focus: 10 hours 5FA04–5GC04 You do not need any other materials. Instructions • This paper should be given to the teacher-examiner for confidential reference AS SOON AS IT IS RECEIVED in the centre in order to plan for the candidates’ preparatory studies period. • This paper is also available on the Edexcel website from January 2010. • Centres are free to devise their own preparatory period of study prior to the 10 hours of sustained focus. • The paper may be given to candidates as soon as it is received, at the centre’s discretion. Edexcel GCSE (Short Course) in Art and Design: Fine Art (5FA04) Edexcel GCSE (Short Course) in Art and Design: Three-Dimensional Design (5TD04) Edexcel GCSE (Short Course) in Art and Design: Textile Design (5TE04) Edexcel GCSE (Short Course) in Art and Design: Photography – Lens and Light-based Media (5PY04) Edexcel GCSE (Short Course) in Art and Design: Graphic Communication (5GC04) Turn over M37313A ©2010 Edexcel Limited. *M37313A* 6/6/6/6/4/ M37313A_GCSE_Art_Design_Unit_2_S1 1 07/10/2009 11:23:57 Candidate guidance Your teacher will be able to teach, guide and support you as you prepare your personal response. You may also complete preparatory work without direct supervision. The preparatory period The process of producing work for assessment may begin once you receive this paper. You should develop your response to the theme in a personal, creative way. The preparatory period consists of approximately 20 hours.