Anne Enright, the Green Road (2015) Lecture 4 of 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December Calendar

December 2019 Spokane Area Diversity/Cultural Events National Universal Human Rights Month The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) was adopted by the UN in 1948 as a response to the Nazi holocaust and to set a standard by which the human rights activities of all nations, rich and poor alike, are to be measured. The United Nations has declared an International Day for Elimination of Violence Against Women. From November 25th through December 10th, Human Rights Day, the 16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence is to raise public awareness and mobilizing people everywhere to bring about change. The 2019 theme for the Elimination of Violence Against Women is ‘Orange the World: Generation Equality Stands Against Rape’. These dates were chosen to commemorate the three Mirabal sisters, who were political activists under Dominican ruler Rafael Trujillo (1930-1961) who ordered their brutal assassinate in 1960. Join the campaign! You can participate in person or on social media via the following hashtags: Use the hashtags: #GenerationEquality #orangetheworld and #spreadtheword. For more information, visit their website at http://www.un.org/en/events/endviolenceday/. ******************************************************************************** As Grandmother Taught: Women, Tradition and Plateau Art Coiled and twined basketry and beaded hats, pouches, bags, dolls, horse regalia, baby boards, and dresses alongside vintage photos of Plateau women wearing or alongside their traditional, handmade clothing and objects, with works by Leanne Campbell, HollyAnna CougarTracks DeCoteau Littlebull and Bernadine Phillips. Dates: August 2018 through December 2019 Time: Tuesday-Sunday, 10:00 am-5:00 pm Location: Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture, 2316 W. First Ave Cost: $10.00 adult, $8.00 seniors, $5.00 children ages 6-17, $8.00 college students with ID. -

The Travelin' Grampa

The Travelin’ Grampa Touring the U.S.A. without an automobile Special Supplement Christmastime Calendar Vol. 8, No. 12, December 2015 Illustration credits: Dec. 1891 Scribner’s magazine; engraving based on 1845 painting by Carl August Schwerdgeburth. Left: The First Christmas Tree, the Oak of Geismar, drawn by Howard Pyle, for a story by that title, by Henry van Dyke in Scribner’s Magazine, Dec. 1891. Pictured is Saint Boniface, in A.D. 772, directing Norsemen to where the tree is to be placed. Right: First Lighted Christmas Tree, said to have been in the home of Martin Luther, in 1510, or maybe 1535. Some scholars claim the first Christmas tree was put on display near Rega, in Latvia, in 1530. Or maybe near Tallinn, in Estonia, in 1510. In the USA, there’s more to Christmastime than Christmas Traveling abroad, Grampa notices most natives tend to resemble one another and share a similar culture. Not here in the USA. Our residents come in virtually every race, creed, skin color and geographic origin. In our country, at this time of year, we celebrate a variety of holidays, in a wide variety of ways. There’s the Feast of the Nativity, aka Christmas, of course. Most celebrate it Dec. 25; others on Jan. 6. Hindus celebrate their 5th day of Pancha Ganapati Dec. 25. There’s Chanukah. Or is it spelled Hanukkah? And let’s not forget Kwanzaa, several year- ending African American holidays invented in 1966 in Long Beach, Calif. Sunni Muslims say Mohammad’s birthday is Dec. 24 this year. -

Historické Základy Environmentalizmu a Environmentálneho Práva (XXV.)

Environmentalistika Historické základy environmentalizmu a environmentálneho práva (XXV.) „Neosvojuj si obyčaj, ktorá sa odchyľuje od zvyklostí Germánmi Julblock. Saturnália, ako spomienka na Zlatý kého Santa Clausa, v roku 1773 prvý raz uvedeného v tvojej krajiny.“ vek ľudstva, keď vládol svetu boh sejby a poľnohospo- americkej tlači. Pravdepodobne pod vplyvom holandských (verš 70 z Poučenia z papyrusu Insinger, okolo 300 prnl., ulože- dárstva Saturnus (podľa sero = siatie), končili Larentaliami - kolonistov v Novom Amsterdame (New Yorku) prevzal ného v múzeu v Leidene) oslavami plodnosti Bohyne matky (Acca Larentia), ktorou na seba vlastnosti severského nebeského vykonávateľa bola neviestka Larenta, matka bôžikov spravodlivosti Thora (anglosaského Thunora, germán- Lárov - ochrancov vnútorného i vonkaj- skeho Donara, keltského Taranosa/Turana, laponského šieho environmentu (domácností i polí), Horagellesa), syna matky zeme Fjördyn/Jörd, preháňajú- prenesene dojka zakladateľov Ríma ceho sa po nebi vo voze ťahanom capmi (inde v kočiari - Romula a Réma asi v roku 753 prnl. ťahanom koňmi, na severe v saniach ťahaných sobmi). Počas Saturnálií sa 18. decembra usku- Sv. Mikuláš prevzal v Európe v 10. storočí viac vlastnosti točnili oslavy pôvodne keltskej patrón- Ódina/Wodena. Postupne sa ujala jeho dobročinnosť, pri- ky koní - bohyne Epona (ako Eponalia), čom posudzoval správanie ľudí, najmä detí, aj vo vzťahu k 19. decembra bohyne Ops (ako Opalia; tiež environmentu – vo Veľkej Británii ako Father Christmas, vo 9. decembra) a 21. decembra slávnosti Francúzsku Papa Noel, v Taliansku Babo Natale, v Nórsku bohyne zimného slnovratu Angerona/ Julenissen, vo Švédsku Julttomten, vo Fínsku Joulupukki, Diva (ako Angeronalia/Divalia, ktoré treba v Portugalsku Pai Natel, V Peru Papa Pére a v Holandsku odlíšiť v čase splnu od indických kvázi Sinter Klaas (kvázi Santa Claus). -

December Calendar

December 2020 Spokane Area Diversity/Cultural Events National Universal Human Rights Month The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) was adopted by the UN in 1948 as a response to the Nazi holocaust and to set a standard by which the human rights activities of all nations, rich and poor alike, are to be measured. The United Nations has declared an International Day for Elimination of Violence Against Women. From November 25th through December 10th, Human Rights Day, the 16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence is to raise public awareness and mobilizing people everywhere to bring about change. The 2020 theme for the Elimination of Violence Against Women is ‘Orange the World: Fund, Respond, Prevent. Collect!’. These dates were chosen to commemorate the three Mirabal sisters, who were political activists under Dominican ruler Rafael Trujillo (1930-1961) who ordered their brutal assassinate in 1960. Join the campaign! You can participate in person or on social media via the following hashtags: Use the hashtags: #GenerationEquality #orangetheworld and #spreadtheword. For more information, visit their website at https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/in- focus/end-violence-against-women. ******************************************************************************** Art Hour Day: Tuesday Time: 4:00 pm – 5:00 pm program includes in-depth interviews with local artists, cultural commentary, and announcements for the creative community and their fans. Hosted by Mike and Eric. On KYRS 92.3 FM or 88.1 FM. Website: http://www.kyrs.org. Can You Queer Me Now? Day: Tuesday Time: 4:00 pm – 4:30 pm Hear voices directly from the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Queer, and Questioning community right here in the Inland Northwest. -

Hutman Productions Publications Each Sale Helps Us to Maintain Our Informational Web Pages

Hutman Productions Publications Mail Order Catalog, 4/17/2020 P R E S E N T S: The Very Best Guides to Traditional Culture, Folklore, And History Not Just a "good read" but Important Pathways to a better life through ancient cultural practices. Each sale helps us to maintain our informational web pages. We need your help! For Prices go Here: http://www.cbladey.com/hutmanbooks/pdfprices.p df Our Address: Hutman Productions P.O. 268 Linthicum, Md. 21090, U.S.A. Email- [email protected] 2 Introduction Publications "Brilliant reference books for all the most challenging questions of the day." -Chip Donahue Hutman Productions is dedicated to the liberation of important resources from decaying books locked away in reference libraries. In order for people to create folk experiences they require information. For singing- people need hymnals. Hutman Productions gathers information and places it on web pages and into publications where it can once again be used to inform, and create folk experiences. Our goal is to promote the active use in folk experiences of the information we publish. We have helped to inform countless weddings, wakes, and celebrations. We have put ancient crafts back into the hands of children. We have given songs to the song less. We have provided delight and wonder to thousands via folklore, folk music and folk tale. We have made this information freely accessible. We could not provide these services were it not for our growing library of 3 publications. Take a moment to look them over. We hope that you too can use them as primary resources to inform the folk experiences of your life. -

Artyclys Podcast Nicholas Williams Wàr Skeulantavas.Com

1 Artyclys Podcast Nicholas Williams wàr skeulantavas.com Hanow Kernowek Hanow Sowsnek Nyver Dedhyans Abram Abram 94 26.11.17 Afodyl Daffodil 8 22.2.16 Airborth Towan Plustry Newquay Airport 215 2.3.10 Airednow Aircraft 224 19.4.20 Alban – Albany Albion – Albany 87 8.10.17 Almayn pò Jermany Germany in Cornish 56 5.2.17 An Balores The Chough 181 8.9.19 An ger ‘bardh’ The word ‘bard’ 129 2.7.18 An Greal Sans The Holy Grail 53 8.1.17 An Gwerryans Brâs The Great War 217 19.12.14 An Gwyns i’n Helyk The Wind in the Willows 192 24.11.19 An Hen-Geltyon The Ancient Celts 186 2.7.14 An Pëth Awartha dhe Woles Upside Down 59 23.2.17 An vledhen eus passys The past year 145 24.12.18 Ana ha Joakym Anna and Joachim 4 17.1.16 Arkymêdês Archimedes 26 3.7.16 Ascallen Thistle 73 25.6.17 Athelstan – Audrey Athelstan – Audrey 76 23.7.17 Augùstùs – mis Est Augustus – August 125 6.8.18 Aval Apple 133 1.10.18 Awan, dowr, ryver River in Cornish 92 12.11.17 Baldùr Baldur 206 12.2.20 Banallen Broom 121 8.7.18 Baner Ùleth The Flag of Ulster 14 29.3.16 Bersabe Bathsheba 118 20.5.18 Bêwnans tavas y gôwsel Beatha teanga a labhairt 71 4.6.17 Bian ha Brâs Small and Great 126 12.8.18 Bledhen Labm Leap Year 10 6.3.16 Bleydhas Wolves 7 14.2.16 Breten Veur ha Breten Vian Great Britain and Little Britain 46 27.11.16 Brithen Tartan 44 13.11.16 Broder Odryk Brother Oderic 140 18.11.18 ‘Brown’ in Kernowek ‘Brown’ in Cornish 166 26.5.19 Bryjet ha’n Werhes Bridget and the Virgin 102 29.1.18 Cabmdhavas Rainbow 20 21.5.16 Caja Vrâs Ox-eye Daisy 34 28.8.16 ‘Cake’ in Kernowek ‘Cake’ in Cornish 205 2.2.20 Calesvol Excalibur 136 21.10.18 Caradar 1 Caradar (A.S.D. -

Celebrating 550 Years of the Sikh Religion Students

see OOddeeoonn cciinneemmaa ttiicckkeettss page WWIINN 36 NOVEMBER 1ST EDITION 2019 Yorkshire & Lancashire A University will be marking 550 years since the founding of the Sikh religion by Celebrating serving up a major free meal to hundreds of students, staff and members of the public. Birmingham City University will host its annual ‘Langar on Campus,’ which 550 years of the provides a free lunch at a special pop-up community kitchen, for visitors from across the city. Continued Sikh religion on page 10 2 Local www.asianexpress.co.uk November 2019 - 1st Edition CONTACT US: Tel : 0113 322 9911 08703 608 606 Pilgrims praise Prime Minister Email : [email protected] Imran Khan stating he had Stories: [email protected] [email protected] Advertising enquiries: [email protected] achieved what could not be Text to mobile : 07772 365 325 done in the last 72 years.” Follow us on Asian Express is available as a FREE WEEKLY pick-up from selected supermarkets, retail outlets, community centres, boutiques, restaurants and many other distribution outlets across the Yorkshire region. So pick-up your FREE copy of Asian Express TODAY! ©Media Buzz. All contents are Copyright. All Rights are reserved. No part of this publication may be stored in any retrieval system or transmitted electronically in any form without prior written permission of the Publishers. Whilst every effort is made to ensure accuracy, no responsibility can be accepted for inaccuracies howsoever caused. Contributed material does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the Publishers. The editorial policy and general layout of this publication are at the discretion of the publisher and no debate will be entered into. -

The 12 Days of Christmas Free Ebook

FREETHE 12 DAYS OF CHRISTMAS EBOOK Robert Sabuda | 14 pages | 02 Oct 2006 | SIMON & SCHUSTER | 9781416926382 | English | New York, United States The 12 Days of Christmas - Christmas Customs and Traditions - whychristmas?com The tunes of collected versions vary. The standard tune now associated with it is derived from a arrangement of a traditional folk melody by English composer Frederic Austinwho introduced the familiar prolongation of the verse "five gold rings" now often "five golden rings". There are twelve verses, each describing a gift given by "my true love" The 12 Days of Christmas one of the twelve days of Christmas. There are many variations in the lyrics. The lyrics given here are from Frederic Austin 's publication that established the current form of the carol. On the first day of Christmas my true love sent to me A partridge in a pear tree. On the second day of Christmas my true love sent to me Two turtle dovesAnd a partridge in a pear tree. On the third day of Christmas my true love sent to me Three French hensTwo turtle doves, And a partridge in a pear tree. Subsequent verses follow the same pattern, each adding one new gift and repeating all the earlier gifts so that each verse is one line longer than its predecessor:. The earliest known version of the lyrics was The 12 Days of Christmas in London under the title "The Twelve Days of Christmas sung at King Pepin's Ball", as part of a children's book, Mirth without Mischief. For ease of comparison with Austin's version given above: a differences in wording, ignoring capitalisation and punctuation, are indicated in italics ; b The 12 Days of Christmas that do not appear at all in Austin's version are indicated in bold italics. -

8 Intermission

The Wren/The King - Fanfare for the King’s Supper - Glocester Wassail ❄ Winter (When Icicles Hang by the Wall) Wren Day, 26 December, is celebrated in Ireland and some other Celtic countries. Crowds of A poem from Shakespere’s “Love’s Labour’s Lost” set to the 16th c. tune “Packington’s Pound.” mummers (sometimes called wrenboys or strawboys) dressed up in masks, straw suits and To keel the pot is to prevent it from boiling over - a cozy image of domestic warmth to contrast colourful motley clothing parade through towns and villages with a fake wren (“the king”) on the chilly references in the verses. top of a decorated pole, accompanied by traditional music. It’s traditional, so it doesn’t have to Tu-whit to who, a merry note / While greasy Joan doth keel the pot make sense. The Fanfare-Rondeau is from the first Suite de Symphonies by Jean-Joseph Mouret, an 18th c. Solstice Song French composer. A song for the turning of the seasons from our friend Karen Gillmore in Victoria BC. "Wassail" from the Anglo-Saxon "wes hal," means "good health" (literally, "be whole"). English World, sun, moon, stars - dance in the circles of night Wassailers went from door to door for ale to fill their cups, and sometimes even a bite to eat. Wind, tide, tree, stone - sing in the cycles of light Wassail, wassail all over the town, Our cup it is white and the ale it is brown. Our cup it is made of the good ashen tree, And so is the malt of the best barley. -

The Nuclear Bible: the Numerology of “26” & “11” (Date of Super Bowl XLV)

The Nuclear Bible: The Numerology of “26” & “11” (Date of Super Bowl XLV) Intro: Understanding the numbers 26 & 11 goes a long way into understanding which days to stay home and avoid public places, and who is responsible for the worst the tragedies that humanity has ever experienced. The 2011 Super Bowl date of February 6, 2011, just happen to include both numbers. Interestingly, Road 2611 just happens to be in Texas where Super Bowl XLV will be played! Source: Wikipedia Title/Headline: Farm To Market Road Abstract: Farm to Market Road 2611 begins where FM 2004 ends at State Highway 36 near Jones Creek. The road follows a western path, crossing the San Bernard River and passing the Churchill Bridge Community. The highway intersects FM 2918, an access highway to the River's End Community and the San Bernard Wildlife Refuge. Making a sharp north, then west curve, FM 2611 continues its western path 10 miles (16 km) south of Sweeny, entering Matagorda County and the Cedar Lake Community. The road comes to its end at the intersection of FM 457, connecting Sargent to Bay City (Wikipedia, 2010). 26 & 11: Scrotum Constellation: Messier object M11, a magnitude 7.0 open cluster in the constellation Scutum, also known as the Wild Duck Cluster. Scutum contains several open clusters, as well as a globular cluster and a planetary nebula. The two best known deep sky objects in Scutum are M11 (NGC 6705), the Wild Duck Cluster, a dense open cluster, and M26, another open cluster also known as NGC 6694. The globular cluster NGC 6712 and the planetary nebula IC 1295 can be found in the eastern part of the constellation, only 24 arcminutes apart (Wikipedia, 2010). -

Multicultural Education

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 1980 Volume VI: The Present as History Multicultural Education Curriculum Unit 80.06.10 by Deborah Possidento Multicultural Education reflects broad humanitarian and democratic goals for equality, justice, understanding, and respect for all people as well as harmony between people of differing cultural backgrounds. Consequently, this unit is designed to bring to the consciousness of children the contributions of all immigrant and migrant groups represented in their classes. This consciousness-raising can be accomplished through the study of a variety of multicultural areas including: family life and roles, foods, religion, recreation, folk crafts, and history. The ethnic groups to be represented in this unit are Black, Hispanic, Jewish, Italian, Portuguese, Chinese, Irish, and Polish. I have chosen these particular ethnic groups because of their contributions to the settlement and development of New Haven and because they are all more or less represented in my classroom. This unit is intended for use in a Foreign Language Exploratory class for seventh and eighth graders. It is focused on a multicultural calendar of ethnic festivals and celebrations, dated from September 1, 1980 through January 6, 1981, concentrating on holidays of major importance to the ethnic groups listed above. I have further provided background information and activities to accompany some of the dates listed on the calendar including: 1. Autumn as a season of Harvest Festivals: Sukkoth, Chinese Harvest Moon Festival, African Harvest Festivals, Halloween. 2. Winter Holidays in response to the winter solstice: Chanukah, Christmas, Kwanza, Three Kings’ Day. The background information is written so that it can be read to students if the teacher chooses. -

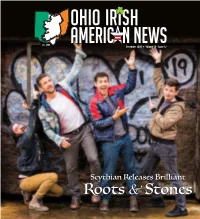

December 2020 • Volume 14 - Issue 12 of Our Neighbors

est. 2006 December 2020 • Volume 14 - Issue 12 of our neighbors. They may be ours, but in our DNA even more, for having gone Editor’s they are not absolute. through it, and then open our hand, ON THIS DAY IN IRISH HISTORY - DECEMBER Corner Regular checkups are always recom- reach down and clasp the hand of those mended. Reality checks cut through coming after? SAFE HOME By John O’Brien, Jr. the glasses and filters of our limited One Country/One Ireland? Growing 7 December 1979 - Charles J. 21 December 1971 - Heinrich Boll, experience, to listen to those with dif- up Irish, we have that code in our DNA. Haughey defeated George Colley author of Irish Journal (1957) and ferent ones. Then and only then, can we Why shouldn’t that same ideal be the to become leader of Fianna Fail; Nobel Laureate (1972), born in @Jobjr WILLIAM LUTHER Í deliberately choose what filters we want mantra for America; be the same for us December 2020 Vol. 14 • Issue 12 Corp. Bill then worked for Ridge Tool he was elected Taoiseach on 11 Cologne. North Olmsted, Ohio to wear going forward, framed by lis- here in the U.S.? Publisher John O’Brien Jr. Co. as the Division Facilities & Environ- December. March 26, 1953 – October 21, 2020 22 December 1969 - Bernadette tening, empathy, values, and if you are We all bear hurts and dreams and Editor John O’Brien Jr. mental Manager, whereby had respon- Design/Production WILLIAM (Bill) 8 December 1939 - James Galway, Devlin was sentenced to six months Christian, hopefully, the word of God.