Historic-Preservation-Resource-Guide.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Greatest Gift Of

Mid-Atlantic Center for the Arts & Humanities MAC VOLUME XLVIV, ISSUE 4 www.capemaymac.org FALL/HOLIDAY 2019 FROM THE PRESIDENT:ewsletter The greatestN gift of all At last year’s Christmas Tree Lighting Ceremony, we thanked Kathy Makowski, Sturdy Savings Bank’s Cape May Branch Manager, for the bank’s generous sponsor- ship of the event. Please join us at the Physick Estate at 7pm on Saturday, November 23 for this year’s ceremony. Sturdy Savings Bank thanked for support Sturdy Savings Bank will again be underwriting the official kick-off of our holiday season, the Christmas Tree Dave and Chris Clemans in front of the Owen Coachman House Lighting Ceremony on the Physick Estate grounds during Holiday Preview On Thursday August 29, with my award from the State of New Jersey and also Weekend. Please join us on Saturday, signature as President, MAC became a placed the Owen Coachman House on the November 23 at 7pm when Santa throws property owner for the first time. The other National Register of Historic Places. They the switch for this festive event, which also important signatures were from Chris and lived up to their promise to the former owners includes a free open house at our Physick Dave Clemans, as they presented MAC to protect these historic treasures for future House Museum, authentically decorated with the largest donation in our history, the generations and felt that MAC was the best for the holidays, as well as the opening of Whalers Cottages, barn and spectacular option to keep that promise going well into the “Old Fashioned Christmas” exhibit grounds at 1017 & 1019 Batts Lane in Lower the future. -

Girard College Historical Collections Founder's Hall, Girard College 2101 S. College Ave, Philadelphia PA 1921 Kathy Haas Dire

Girard College Historical Collections Founder’s Hall, Girard College 2101 S. College Ave, Philadelphia PA 1921 Kathy Haas Director of Historical Resources [email protected]; 215-787-4434 The Girard College Historical Collections preserve and interprets historical materials associated with Stephen Girard and Girard College. Stephen Girard (1750 –1831) was a French-born, naturalized American, who made a fortune as a mariner, merchant, banker and landowner. He ran the fever hospital at Bush Hill during the Yellow Fever epidemic of 1793, saved the U.S. government from financial collapse during the War of 1812, and died as one of the wealthiest men in American history. In his will he bequeathed nearly his entire fortune to charity, including an endowment for establishing a boarding school for "poor, white, male" orphans in Philadelphia. Today Girard College is multi- racial and co-educational; it continues to serve academically capable students from families with limited financial resources. Stephen Girard willed his papers and possessions to the school he created; today this uniquely well-preserved collection of 500 objects and 100,000 pages of letters, ledgers, craftsman bills, maritime records, hospital records etc. gives insight not only into Girard but also into the world of early national Philadelphia. The papers segment of this collection is also available to researchers on microfilm at the American Philosophical Society. The Girard College Historical Collections also chronicle the history of the unprecedented school Girard endowed for disadvantaged youth and provide resources for the study of educational, architectural and Philadelphia history through tens of thousands of thousands of photographs, archival records, and objects. -

VIII. VIGNETTES: Public & Private Buildings and Structures Date Cartographer Or Publisher Map # Adams County-1853 (Hopkins)

VIII. VIGNETTES: Public & Private Buildings and Structures Date Cartographer or Publisher Map # Adams County-1853 (Hopkins) (Inset) 22 Public School; Evangelical Lutheran Theological Seminary; County Prison; Eagle Hotel; Pennsylvania College, Gettysburg. Also, business establishments and private residences. Allegheny County, 1862 (Beers)(Inset) 30 Pittsburgh Water Company; Iron City College; Saving Bank. Bedford County, 1861 (Walker) (Inset) 72 Court House & Jail; Bedford Mineral Springs. Berks County, 1821 (Bridgens) (Inset) 121 Charles Evans Cemetery; Court House; Berks County Prison. Bradford County, 1858 (Barker) (Inset) 334 Court House; Asylum; Capitol at Harrisburg; State Lunatic Hospital. Also, business establishments and private residences. Bucks, Montgomery and Philadelphia City [1857] (King, Shrope, et.al.) (Inset) 12 Court Houses, Bucks & Montgomery Counties; Adelphum Institute; Female Seminary, Pottstown; Oakland Female Institute, Norristown; Tremont Seminary (Male), Norristown. Centre County, 1861 (Walling) (Inset) 23 Court House; Farmer's High School of Pennsylvania Clarion County, 1865 (Pomeroy) (Inset) 206 Court House; Alexander House, Clarion. Pennsylvania Cumberland County, 1858 (Bridgens) (Inset) 75 Court House, Carlisle. Dauphin & Lebanon Counties, 1818 (T. Smith) (Inset) 82 Hunter' s Falls. Dauphin County, 1858 (Southwick) (Inset) 38 Capitol; Court House; Pennsylvania State Lunatic Hospital, Harrisburg. Also, business establishments and private residences. Dauphin County, 1862 (Beers) (Inset) 76 Business establishments and private residences. Erie County, 1855 (McLeran-Moore) (Inset) 134 Court House; Brown's Hotel; Girard Academy; Waterford Academy; Eagle Hotel; West Springfield Academy; Block House; Post Office. Nature Scenes. Franklin County, 1858 (Davison) (Inset) 21 Court House; Franklin and Greencastle Hotels; Female Seminary, Fayetteville. Also, business establishments and private residences. Freeport, Armstrong County, 1854 (Doran) (Inset) 200 Business establishments and private residences. -

Mid-Atlantic Center for the Arts & Humanities

Mid-Atlantic Center for the Arts & Humanities MAC VOLUME XLVIII, ISSUE 4N www.capemaymac.orgewsletter FALL/HOLIDAY 2018 At our Volunteer Recognition Reception on April 30, Sturdy Savings Bank officials Kathy Makowski and Michael Lloyd (center) were c. 1890 view of the 1879 Physick House Architect “Fearless Frank” Furness thanked for their generous support by MAC Director Michael Zuckerman (left) and 1st Physick House/Furness mystery solved Vice President Brian Groetsch. Sturdy Savings Bank Ever since MAC was formed in 1970 to (“upside down”) chimneys, jerkinhead save the Physick Estate from demolition, a dormers and Stick porch brackets. But thanked for support cloud of mystery has hovered over precisely they’ve never been able to find one shred of who designed the main Physick House. Local documentary evidence to back up this claim Sturdy Savings Bank will again newspapers reported on its construction (sadly, Furness’ wife threw out most of his be underwriting the official kick-off of in 1878-79, giving credit to local builder office files upon his death in 1912). So, we’ve our holiday season, the Christmas Tree Charles Shaw but making no mention of its been left with the rather lame “attributed to Lighting Ceremony on the Physick architect. Over the decades, a steady stream Frank Furness” in all of our descriptive copy Estate grounds during Holiday Preview of architectural historians (including George on our Physick House Museum. Weekend. Please join us on Saturday, E. Thomas, Hyman Myers and Hugh Happily, this frustrating state of affairs November 17 at 7pm when Santa throws McCauley) have declared that it could only was brought to an abrupt close several weeks the switch for this festive event, which also have been designed by one person, renowned ago, thanks to the efforts of local architectural includes a free open house at our Physick Philadelphia architect Frank Furness (best historian/preservationist Pip (Phillipa) House Museum, authentically decorated known for his Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Campbell. -

Beyond the Established Norms: a New Kind of Union Activism

BEYOND THE ESTABLISHED NORMS: A NEW KIND OF UNION ACTIVISM LOCAL 3 • AFL-CIO Philadelphia Federation of Teachers Health & Welfare Fund’s Professional Development 1974-2014 PFT HEALTH & WELFARE FUND AND TEMPLE UNIVERSITY The PFT Health & Welfare Fund’s ER&D program and Temple Univer- sity worked together to provide PFT members with three graduate level courses to improve their effectiveness in the classroom. The courses offered were Beginning Reading Instruction, Foundations for Effective Teaching and Managing Student Behavior. The Fund acknowledges the following members of the Educational Issues PARTNERSHIP WITH CHEYNEY UNIVERSITY team for their role in the creation of Beyond the Established Norms: Camina Ceasar, Sandra Dunham, Marcia Hinton, Joyce Jones, Rosalind Jones Johnson, In 2008, the PFT Health & Welfare Fund and Cheyney University worked together to provide Philadel- phia teachers with high quality, peer-led professional development at Cheyney University’s urban cam- and Linda Whitaker. pus in Philadelphia. CHEYNEY UNIVERSITY PARTNERSHIP Rosalind Jones Johnson, keynote speaker for Cheyney University’s graduation hooding ceremony joins Dr. Michelle Vitale, President of Cheyney University and Dr. John Williams, Dean of Graduate Studies. Published January 2015 59 Table of Contents History Introduction . 4 Programs for Teaching Annual Conference . 6 QuEST Schools . 8 Philadelphia QuEST Professional Development . 12 Pennsylvania Department of Education Act 48 Provider . 13 Customized Professional Development . 13 On-Site School Support . 14 ER&D (Educational Research and Dissemination) . 16 New Unionism . 20 PFT Health & Welfare Fund and Cheyney University of Pennsylvania Collaborative . 20 PFT Health & Welfare Fund Did Not Get the Credit it Deserved . 23 Programs Philadelphia QuEST Reading Recovery . -

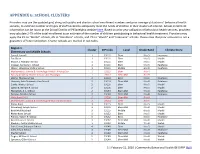

School Cluster List

APPENDIX G: SCHOOL CLUSTERS Providers may use the updated grid, along with public and charter school enrollment numbers and prior average utilization of behavioral health services, to estimate number and types of staff needed to adequately meet the needs of children in their clusters of interest. School enrollment information can be found at the School District of Philadelphia website here. Based on prior year utilization of behavioral health services, providers may calculate 2-7% of the total enrollment as an estimate of the number of children participating in behavioral health treatment. Providers may apply the 2% to “Model” schools, 4% to “Reinforce” schools, and 7% to “Watch” and “Intervene” schools. Please note that prior utilization is not a guarantee of future utilization. Charter schools are marked in red italics. Region 1 Cluster ZIP Code Level Grade Band Climate Score Elementary and Middle Schools Carnell, Laura H. 1 19111 Elem K to 5 Intervene Fox Chase 1 19111 Elem K to 5 Model Moore, J. Hampton School 1 19111 Elem K to 5 Model Crossan, Kennedy C. School 1 19111 Elem K to 5 Reinforce Wilson, Woodrow Middle School 1 19111 Middle 6 to 8 Reinforce Mathematics, Science & Technology II-MaST II Rising Sun 1 19111 Elem K to 4 Tacony Academy Charter School - Am. Paradigm 1 19111 Elem-Mid K to 8 Holme, Thomas School 2 19114 Elem K to 6 Reinforce Hancock, John Demonstration School 2 19114 Elem-Mid K to 8 Reinforce Comly, Watson School 2 19116 Elem K to 5 Model Loesche, William H. School 2 19116 Elem K to 5 Model Fitzpatrick, A. -

The Battles of Germantown: Public History and Preservation in America’S Most Historic Neighborhood During the Twentieth Century

The Battles of Germantown: Public History and Preservation in America’s Most Historic Neighborhood During the Twentieth Century Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By David W. Young Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Steven Conn, Advisor Saul Cornell David Steigerwald Copyright by David W. Young 2009 Abstract This dissertation examines how public history and historic preservation have changed during the twentieth century by examining the Germantown neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Founded in 1683, Germantown is one of America’s most historic neighborhoods, with resonant landmarks related to the nation’s political, military, industrial, and cultural history. Efforts to preserve the historic sites of the neighborhood have resulted in the presence of fourteen historic sites and house museums, including sites owned by the National Park Service, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and the City of Philadelphia. Germantown is also a neighborhood where many of the ills that came to beset many American cities in the twentieth century are easy to spot. The 2000 census showed that one quarter of its citizens live at or below the poverty line. Germantown High School recently made national headlines when students there attacked a popular teacher, causing severe injuries. Many businesses and landmark buildings now stand shuttered in community that no longer can draw on the manufacturing or retail economy it once did. Germantown’s twentieth century has seen remarkably creative approaches to contemporary problems using historic preservation at their core. -

OLMSTED TRACT; Torrance, California 2011 – 2013 SURVEY of HISTORIC RESOURCES

OLMSTED TRACT; Torrance, California 2011 – 2013 SURVEY OF HISTORIC RESOURCES II. HISTORIC CONTEXT STATEMENT A. Torrance and Garden City Movement: The plan for the original City of Torrance, known as the Olmsted Tract, owes its origins to a movement that begin in England in the late 19th Century. Sir Ebenezer Howard published his manifesto “Garden Cities of To-morrow" in 1898 where he describes a utopian city in which man lives harmoniously together with the rest of nature. The London suburbs of Letchworth Garden City and Welwyn Garden City were the first built examples of garden city planning and became a model for urban planners in America. In 1899 Ebenezer founded the Garden City Association to promote his idea for the Garden City ‘in which all the advantages of the most energetic town life would be secured in perfect combination with all the beauty and delight of the country.” His notions about the integration of nature with town planning had profound influence on the design of cities and the modern suburb in the 20th Century. Examples of Garden City Plans in America include: Forest Hills Gardens, New York (by Fredrick Law Olmsted Jr.); Radburn, New Jersey; Shaker Heights, Ohio; Baldwin Hills Village, in Los Angeles, California and Greenbelt, Maryland. Fredrick Law Olmsted is considered to be the father of the landscape architecture profession in America. He had two sons that inherited his legacy and firm. They practiced as the Olmsted Brothers of Brookline Massachusetts. Fredrick Law Olmsted Junior was a founding member of The National Planning Institute of America and was its President from 1910 to 1919. -

Deshler-Morris House

DESHLER-MORRIS HOUSE Part of Independence National Historical Park, Pennsylvania Sir William Howe YELLOW FEVER in the NATION'S CAPITAL DAVID DESHLER'S ELEGANT HOUSE In 1790 the Federal Government moved from New York to Philadelphia, in time for the final session of Germantown was 90 years in the making when the First Congress under the Constitution. To an David Deshler in 1772 chose an "airy, high situation, already overflowing commercial metropolis were added commanding an agreeable prospect of the adjoining the offices of Congress and the executive departments, country" for his new residence. The site lay in the while an expanding State government took whatever center of a straggling village whose German-speaking other space could be found. A colony of diplomats inhabitants combined farming with handicraft for a and assorted petitioners of Congress clustered around livelihood. They sold their produce in Philadelphia, the new center of government. but sent their linen, wool stockings, and leatherwork Late in the summer of 1793 yellow fever struck and to more distant markets. For decades the town put a "strange and melancholy . mask on the once had enjoyed a reputation conferred by the civilizing carefree face of a thriving city." Fortunately, Congress influence of Christopher Sower's German-language was out of session. The Supreme Court met for a press. single day in August and adjourned without trying a Germantown's comfortable upland location, not far case of importance. The executive branch stayed in from fast-growing Philadelphia, had long attracted town only through the first days of September. Secre families of means. -

QUES in ARCH HIST I Jump to Today Questions in Architectural History 1

[email protected] - QUES IN ARCH HIST I Jump to Today Questions in Architectural History 1 Faculty: Zeynep Çelik Alexander, Reinhold Martin, Mabel O. Wilson Teaching Fellows: Oskar Arnorsson, Benedict Clouette, Eva Schreiner Thurs 11am-1pm Fall 2016 This two-semester introductory course is organized around selected questions and problems that have, over the course of the past two centuries, helped to define architecture’s modernity. The course treats the history of architectural modernity as a contested, geographically and culturally uncertain category, for which periodization is both necessary and contingent. The fall semester begins with the apotheosis of the European Enlightenment and the early phases of the industrial revolution in the late eighteenth century. From there, it proceeds in a rough chronology through the “long” nineteenth century. Developments in Europe and North America are situated in relation to worldwide processes including trade, imperialism, nationalism, and industrialization. Sequentially, the course considers specific questions and problems that form around differences that are also connections, antitheses that are also interdependencies, and conflicts that are also alliances. The resulting tensions animated architectural discourse and practice throughout the period, and continue to shape our present. Each week, objects, ideas, and events will move in and out of the European and North American frame, with a strong emphasis on relational thinking and contextualization. This includes a historical, relational understanding of architecture itself. Although the Western tradition had recognized diverse building practices as “architecture” for some time, an understanding of architecture as an academic discipline and as a profession, which still prevails today, was only institutionalized in the European nineteenth century. -

Journal of the American Institute of ARCH Itecr·S

Journal of The American Institute of ARCH ITEcr·s PETEil HARRISON November, 1946 Fellowship Honors in The A.I.A. Examinations in Paris-I Architectural Immunity Honoring Louis Sullivan An Editorial by J. Frazer Smith The Dismal Fate of Christopher Renfrew What and Why Is an Industrial Designer? 3Sc PUBLISHED MONTHLY AT THE OCTAGON, WASHINGTON, D. C. UNiVERSITY OF ILLINOJS SMALL HOM ES COUNCIL MUMFORD ~O U SE "JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS NOVEMBER, 1946 VoL. VI, No. 5 Contents Fellowship Honors in The Ameri- Architectural Immunity 225 can Institute of Architects .... 195 By Daniel Paul Higgins By Edgar I. Williams, F.A.I.A. News of the Chapters and Other Honors . 199 Organizations . 228 Examinations in Paris-I .... 200 The Producers' Council. 231 By Huger Elliott The Dismal Fate of Christopher Architects Read and Write: Renfrew . 206 By Robert W. Schmertz "Organic Architecture" . 232 By William G. Purcell Honoring Louis Sullivan By Charles D. Maginnis, Advertising for Architects. 233 F.A.I.A. 208 By 0. H. Murray By William W. Wurster . 209 A Displaced Architect without Chapters of The A.I.A. 213 Documents . 233 By ]. Frazer Smith By Pian Drimmalen What and Why Is an Industrial News of the Educational Field. 234 Designer?. 217 By Philip McConnell The Editor's Asides . 236 ILLUSTRATIONS Tablet marking birth site of Louis H. Sullivan in Boston .. 211 Fur Shop in the Jay Jacob Store, Seattle, Wash .......... 212 George W. Stoddard and Associates, architects Remodeled Country House of Col. Henry W . Anderson, Dinwiddie Co., Va. 221 Duncan Lee, architect Do you know this building? ...... -

![[Pennsylvania County Histories]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1780/pennsylvania-county-histories-711780.webp)

[Pennsylvania County Histories]

REFEI IENCE Ji ffi OOLLE( ]TIONS S-A 9"7 Y.<P H VCf Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2018 with funding from This project is made possible by a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services as administered by the Pennsylvania Department of Education through the Office of Commonwealth Libraries https://archive.org/details/pennsylvaniacoun66unse as ... > . INDEX, Page B Page ft <H 4 • H 'p5 'i'T* ^ l I y,bV INDEX. 5age S '1 ' 3age Pag* "S i • s . *■ • • W T uv w IL . 1. , j ’■- w* W ■ : XYZ . I r—;-- Mb . ,_ tr_ .... »> '' mi - . ■ nothing? It is rather a new method to white- I “ nuts for future historians TO CRACK.” * wash one’s “great-grandfather” by blacken-P % ing another man’s “grandfather.” Is it to ' Immense and '(Overwhelming in importance j make money ? Alas! Mr. Editor, for the to future historians as Mr. Smith’s work is, j sake’ of decency I regret to say it is. t we confess after cracking his nuts we found! The long delay in the publication, the the kernels to be wretchedly shrivelled-up i frequent announcements in the newspapers affairs. They are, most of them, what Mr. 1 of what teas to appear, as though held Toots would say, “ decidedly of no conse- | I in terror en% over parties known to be j quence.” After investigating his labors we 1 ■ sensitive on the subject, conclusively show <; have arrived at this conclusion, that the:| Cr' this to be the object. But if more be author, notwithstanding his literary anteee-! wanting, Mr.