CHRG-116Hhrg40505.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Key Committees 2021

Key Committees 2021 Senate Committee on Appropriations Visit: appropriations.senate.gov Majority Members Minority Members Patrick J. Leahy, VT, Chairman Richard C. Shelby, AL, Ranking Member* Patty Murray, WA* Mitch McConnell, KY Dianne Feinstein, CA Susan M. Collins, ME Richard J. Durbin, IL* Lisa Murkowski, AK Jack Reed, RI* Lindsey Graham, SC* Jon Tester, MT Roy Blunt, MO* Jeanne Shaheen, NH* Jerry Moran, KS* Jeff Merkley, OR* John Hoeven, ND Christopher Coons, DE John Boozman, AR Brian Schatz, HI* Shelley Moore Capito, WV* Tammy Baldwin, WI* John Kennedy, LA* Christopher Murphy, CT* Cindy Hyde-Smith, MS* Joe Manchin, WV* Mike Braun, IN Chris Van Hollen, MD Bill Hagerty, TN Martin Heinrich, NM Marco Rubio, FL* * Indicates member of Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Subcommittee, which funds IMLS - Final committee membership rosters may still be being set “Key Committees 2021” - continued: Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Visit: help.senate.gov Majority Members Minority Members Patty Murray, WA, Chairman Richard Burr, NC, Ranking Member Bernie Sanders, VT Rand Paul, KY Robert P. Casey, Jr PA Susan Collins, ME Tammy Baldwin, WI Bill Cassidy, M.D. LA Christopher Murphy, CT Lisa Murkowski, AK Tim Kaine, VA Mike Braun, IN Margaret Wood Hassan, NH Roger Marshall, KS Tina Smith, MN Tim Scott, SC Jacky Rosen, NV Mitt Romney, UT Ben Ray Lujan, NM Tommy Tuberville, AL John Hickenlooper, CO Jerry Moran, KS “Key Committees 2021” - continued: Senate Committee on Finance Visit: finance.senate.gov Majority Members Minority Members Ron Wyden, OR, Chairman Mike Crapo, ID, Ranking Member Debbie Stabenow, MI Chuck Grassley, IA Maria Cantwell, WA John Cornyn, TX Robert Menendez, NJ John Thune, SD Thomas R. -

Political Report

To: NOW Board of Directors From: Linda Berg Date: July 10, 2019 Political Report 2019 Elections Only 4 states have legislative elections in 2019: Virginia, Mississippi, Louisiana and New Jersey. Although each state’s election is important for redistricting and legislative goals, we are prioritizing Virginia because of its unique opportunity to elect a legislature which can deliver the final state for ERA ratification. If 2 seats are flipped in the House of Delegates and State Senate the Democrats will control the legislature as well as the executive branch. Virginia has been trending more blue, and we made historic gains in the 2017 elections. Victory is within our reach, and with it enormous opportunity for constitutional equality. NOW is working closely with the Feminist Majority to develop a winning field Virginia plan. Additionally, since ominous reproductive rights legislation has been coming out of Louisiana we hope to take advantage of opportunity for feminist change in that state. 2020 Elections It is very exciting that there are still 5 previously NOW PAC endorsed incumbent members of Congress still in the presidential race: Elizabeth Warren, Kamala Harris, Amy Klobuchar, Kirsten Gillibrand, and Tulsi Gabbard. All of them did well in the first set of presidential debates and the further this field continues the more normalizing it will become to have women seriously contending for the office. Although the field looked bright as we looked ahead to the 2020 Senate races, our opportunities have narrowed. We need to pick up 3 seats if we win back the presidency and 4 seats if not. -

September 4, 2020 the Honorable

September 4, 2020 The Honorable Wilbur L. Ross, Jr. The Honorable Steven Dillingham, Ph.D. Secretary Director U.S. Department of Commerce U.S. Census Bureau 1401 Constitution Avenue, N.W. 4600 Silver Hill Road Washington, DC 20230 Washington, DC 20233 Dear Secretary Ross and Director Dillingham: As Members of Michigan’s Congressional Delegation, we write to raise our concerns about the Census Bureau’s decision to shorten the 2020 Census enumeration timeline from October 31 to September 30, 2020, and to compress vital data processing activities into three months from six months. Given that our nation is grappling with the devastating effects of the coronavirus pandemic, it is imperative that we prioritize the implementation of a fair and accurate 2020 decennial Census to ensure recovery funding and other federal resources are directed to the communities most in need. Therefore, we strongly urge you to revise the enumeration deadline back to October 31, 2020 to ensure that the Census Bureau has adequate time to count residents, in light of the challenges posed by the public health crisis and to extend statutory data delivery timelines by 120 calendar days. The recent decision to rush remaining field operations calls into question how the Census Bureau will effectively and accurately count millions of households that did not respond to the Census count on their own, especially in communities hit hardest by the pandemic. On April 13, 2020, the U.S. Department of Commerce and the U.S. Census Bureau issued a joint statement announcing adjustments to 2020 operations, citing challenges related to public health and ensuring an accurate count of all communities.1 In the statement, the Census Bureau sought statutory relief from Congress, requesting 120 additional calendar days to allow for apportionment counts, with a comparable extension of the deadline for releasing redistricting data. -

August 10, 2021 the Honorable Nancy Pelosi the Honorable Steny

August 10, 2021 The Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Honorable Steny Hoyer Speaker Majority Leader U.S. House of Representatives U.S. House of Representatives Washington, D.C. 20515 Washington, D.C. 20515 Dear Speaker Pelosi and Leader Hoyer, As we advance legislation to rebuild and renew America’s infrastructure, we encourage you to continue your commitment to combating the climate crisis by including critical clean energy, energy efficiency, and clean transportation tax incentives in the upcoming infrastructure package. These incentives will play a critical role in America’s economic recovery, alleviate some of the pollution impacts that have been borne by disadvantaged communities, and help the country build back better and cleaner. The clean energy sector was projected to add 175,000 jobs in 2020 but the COVID-19 pandemic upended the industry and roughly 300,000 clean energy workers were still out of work in the beginning of 2021.1 Clean energy, energy efficiency, and clean transportation tax incentives are an important part of bringing these workers back. It is critical that these policies support strong labor standards and domestic manufacturing. The importance of clean energy tax policy is made even more apparent and urgent with record- high temperatures in the Pacific Northwest, unprecedented drought across the West, and the impacts of tropical storms felt up and down the East Coast. We ask that the infrastructure package prioritize inclusion of a stable, predictable, and long-term tax platform that: Provides long-term extensions and expansions to the Production Tax Credit and Investment Tax Credit to meet President Biden’s goal of a carbon pollution-free power sector by 2035; Extends and modernizes tax incentives for commercial and residential energy efficiency improvements and residential electrification; Extends and modifies incentives for clean transportation options and alternative fuel infrastructure; and Supports domestic clean energy, energy efficiency, and clean transportation manufacturing. -

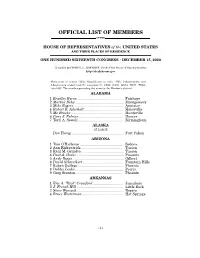

Official List of Members

OFFICIAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES of the UNITED STATES AND THEIR PLACES OF RESIDENCE ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS • DECEMBER 15, 2020 Compiled by CHERYL L. JOHNSON, Clerk of the House of Representatives http://clerk.house.gov Democrats in roman (233); Republicans in italic (195); Independents and Libertarians underlined (2); vacancies (5) CA08, CA50, GA14, NC11, TX04; total 435. The number preceding the name is the Member's district. ALABAMA 1 Bradley Byrne .............................................. Fairhope 2 Martha Roby ................................................ Montgomery 3 Mike Rogers ................................................. Anniston 4 Robert B. Aderholt ....................................... Haleyville 5 Mo Brooks .................................................... Huntsville 6 Gary J. Palmer ............................................ Hoover 7 Terri A. Sewell ............................................. Birmingham ALASKA AT LARGE Don Young .................................................... Fort Yukon ARIZONA 1 Tom O'Halleran ........................................... Sedona 2 Ann Kirkpatrick .......................................... Tucson 3 Raúl M. Grijalva .......................................... Tucson 4 Paul A. Gosar ............................................... Prescott 5 Andy Biggs ................................................... Gilbert 6 David Schweikert ........................................ Fountain Hills 7 Ruben Gallego ............................................ -

September 22, 2020 the Honorable Nancy Pelosi the Honorable Kevin

September 22, 2020 The Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Honorable Kevin McCarthy U.S. House of Representatives U.S. House of Representatives H-232, U.S. Capitol Building H-204, U.S. Capitol Building Washington, DC 20515 Washington, DC 20515 Dear Speaker Pelosi and Leader McCarthy: We write to express our concerns about the status of ongoing negotiations for a relief package to confront the dual public health and economic crises Americans are facing as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. It has been suggested by some that Members of Congress are anxious to return to their districts to campaign in advance of the November 3rd election, even if that means leaving Capitol Hill without passing another COVID-19 relief bill. We want to be very clear that we do not in any way agree with this position. We strongly believe that until the House has successfully sent new, bipartisan COVID-19 relief legislation to the Senate, our place of duty remains here in the People’s House. We were elected to represent the best interests of our constituents and the country. Our constituents' expectations in the midst of this crisis are that we not only rise to the occasion and stay at the table until we have delivered the relief they so desperately need, but also that we set aside electoral politics and place the needs of the country before any one region, faction, or political party. Our constituents do not want us home campaigning while businesses continue to shutter, families struggle to pay the bills, food bank lines lengthen, schools struggle to reopen, pressures grow on hospital systems, and state and local budget shortfalls mean communities consider layoffs for first responders and teachers. -

Congress of the United States Washington D.C

Congress of the United States Washington D.C. 20515 April 29, 2020 The Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Honorable Kevin McCarthy Speaker of the House Minority Leader United States House of Representatives United States House of Representatives H-232, U.S. Capitol H-204, U.S. Capitol Washington, D.C. 20515 Washington, D.C. 20515 Dear Speaker Pelosi and Leader McCarthy: As Congress continues to work on economic relief legislation in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, we ask that you address the challenges faced by the U.S. scientific research workforce during this crisis. While COVID-19 related-research is now in overdrive, most other research has been slowed down or stopped due to pandemic-induced closures of campuses and laboratories. We are deeply concerned that the people who comprise the research workforce – graduate students, postdocs, principal investigators, and technical support staff – are at risk. While Federal rules have allowed researchers to continue to receive their salaries from federal grant funding, their work has been stopped due to shuttered laboratories and facilities and many researchers are currently unable to make progress on their grants. Additionally, researchers will need supplemental funding to support an additional four months’ salary, as many campuses will remain shuttered until the fall, at the earliest. Many core research facilities – typically funded by user fees – sit idle. Still, others have incurred significant costs for shutting down their labs, donating the personal protective equipment (PPE) to frontline health care workers, and cancelling planned experiments. Congress must act to preserve our current scientific workforce and ensure that the U.S. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 117 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 117 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 167 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 21, 2021 No. 163 House of Representatives The House met at 9 a.m. and was To these iconic images, history has school sweetheart, 4.1 GPA at Oakmont called to order by the Speaker pro tem- now added another: that of a young High School, ‘‘one pretty badass ma- pore (Mrs. DEMINGS). marine sergeant in full combat gear rine,’’ as her sister put it. She could f cradling a helpless infant in her arms have done anything she wanted, and amidst the unfolding chaos and peril in what she wanted most was to serve her DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO the besieged Kabul Airport and pro- country and to serve humanity. TEMPORE claiming: ‘‘I love my job.’’ Who else but a guardian angel amidst The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- The entire story of the war in Af- the chaos and violence of those last fore the House the following commu- ghanistan is told in this picture: the days in Kabul could look beyond all nication from the Speaker: sacrifices borne by young Americans that and look into the eyes of an infant WASHINGTON, DC, who volunteered to protect their coun- and proclaim: ‘‘I love my job’’? September 21, 2021. try from international terrorism, the Speaking of the fallen heroes of past I hereby appoint the Honorable VAL BUT- heroism of those who serve their coun- wars, James Michener asked the haunt- LER DEMINGS to act as Speaker pro tempore try even when their country failed ing question: Where do we get such on this day. -

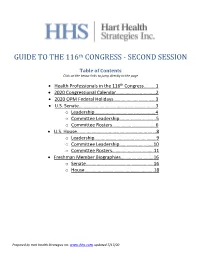

GUIDE to the 116Th CONGRESS

th GUIDE TO THE 116 CONGRESS - SECOND SESSION Table of Contents Click on the below links to jump directly to the page • Health Professionals in the 116th Congress……….1 • 2020 Congressional Calendar.……………………..……2 • 2020 OPM Federal Holidays………………………..……3 • U.S. Senate.……….…….…….…………………………..…...3 o Leadership…...……..…………………….………..4 o Committee Leadership….…..……….………..5 o Committee Rosters……….………………..……6 • U.S. House..……….…….…….…………………………...…...8 o Leadership…...……………………….……………..9 o Committee Leadership……………..….…….10 o Committee Rosters…………..…..……..…….11 • Freshman Member Biographies……….…………..…16 o Senate………………………………..…………..….16 o House……………………………..………..………..18 Prepared by Hart Health Strategies Inc. www.hhs.com, updated 7/17/20 Health Professionals Serving in the 116th Congress The number of healthcare professionals serving in Congress increased for the 116th Congress. Below is a list of Members of Congress and their area of health care. Member of Congress Profession UNITED STATES SENATE Sen. John Barrasso, MD (R-WY) Orthopaedic Surgeon Sen. John Boozman, OD (R-AR) Optometrist Sen. Bill Cassidy, MD (R-LA) Gastroenterologist/Heptalogist Sen. Rand Paul, MD (R-KY) Ophthalmologist HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Rep. Ralph Abraham, MD (R-LA-05)† Family Physician/Veterinarian Rep. Brian Babin, DDS (R-TX-36) Dentist Rep. Karen Bass, PA, MSW (D-CA-37) Nurse/Physician Assistant Rep. Ami Bera, MD (D-CA-07) Internal Medicine Physician Rep. Larry Bucshon, MD (R-IN-08) Cardiothoracic Surgeon Rep. Michael Burgess, MD (R-TX-26) Obstetrician Rep. Buddy Carter, BSPharm (R-GA-01) Pharmacist Rep. Scott DesJarlais, MD (R-TN-04) General Medicine Rep. Neal Dunn, MD (R-FL-02) Urologist Rep. Drew Ferguson, IV, DMD, PC (R-GA-03) Dentist Rep. Paul Gosar, DDS (R-AZ-04) Dentist Rep. -

MICHIGAN REPORT an Analysis of the Jewish Electorate for the Jewish Electorate Institute by the American Jewish Population Project

A Report by the AmericanAmerican Jewish Jewish Population Population Project Project MICHIGAN REPORT An Analysis of the Jewish Electorate for the Jewish Electorate Institute by the American Jewish Population Project At the request of the non-partisan Jewish Electorate Institute, researchers at the American Jewish Population Project at Brandeis University’s Steinhardt Social Research Institute conducted an analysis of hundreds of national surveys of US adults to describe the Jewish electorate in each of the 435 districts of the 116th US Congress and the District of Columbia. Surveys include the American National Election Studies, the General Social Survey, Pew Political and social surveys, the Gallup Daily Tracking poll, and the Gallup Poll Social Series. Data from over 1.4 million US adults were statistically combined to provide, for each district, estimates of the number of adults who self-identify as Jewish and a breakdown of those individuals by age, education, race and ethnicity, political party, and political ideology. The percentages of political identity are not sensitive to quick changes in attitudes that can result from current events and they are not necessarily indicative of voting behaviors. The following report presents a portrait of the Jewish electorate in Michigan and its 14 congressional districts.¹ Daniel Kallista Raquel Magidin de Kramer February 2021 Daniel Parmer Xajavion Seabrum Elizabeth Tighe Leonard Saxe Daniel Nussbaum ajpp.brandeis.edu American Jewish Population Project Michigan is home to ~105,000 Jewish adults, comprising 1.4% of the state's electorate.² Worth 16 electoral votes, the state was won narrowly by Donald Trump (+0.23%; 10,704 votes) in 2016 and by President Biden in (+2.8%; 154,188 votes) in 2020. -

State Delegations

STATE DELEGATIONS Number before names designates Congressional district. Senate Republicans in roman; Senate Democrats in italic; Senate Independents in SMALL CAPS; House Democrats in roman; House Republicans in italic; House Libertarians in SMALL CAPS; Resident Commissioner and Delegates in boldface. ALABAMA SENATORS 3. Mike Rogers Richard C. Shelby 4. Robert B. Aderholt Doug Jones 5. Mo Brooks REPRESENTATIVES 6. Gary J. Palmer [Democrat 1, Republicans 6] 7. Terri A. Sewell 1. Bradley Byrne 2. Martha Roby ALASKA SENATORS REPRESENTATIVE Lisa Murkowski [Republican 1] Dan Sullivan At Large – Don Young ARIZONA SENATORS 3. Rau´l M. Grijalva Kyrsten Sinema 4. Paul A. Gosar Martha McSally 5. Andy Biggs REPRESENTATIVES 6. David Schweikert [Democrats 5, Republicans 4] 7. Ruben Gallego 1. Tom O’Halleran 8. Debbie Lesko 2. Ann Kirkpatrick 9. Greg Stanton ARKANSAS SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES John Boozman [Republicans 4] Tom Cotton 1. Eric A. ‘‘Rick’’ Crawford 2. J. French Hill 3. Steve Womack 4. Bruce Westerman CALIFORNIA SENATORS 1. Doug LaMalfa Dianne Feinstein 2. Jared Huffman Kamala D. Harris 3. John Garamendi 4. Tom McClintock REPRESENTATIVES 5. Mike Thompson [Democrats 45, Republicans 7, 6. Doris O. Matsui Vacant 1] 7. Ami Bera 309 310 Congressional Directory 8. Paul Cook 31. Pete Aguilar 9. Jerry McNerney 32. Grace F. Napolitano 10. Josh Harder 33. Ted Lieu 11. Mark DeSaulnier 34. Jimmy Gomez 12. Nancy Pelosi 35. Norma J. Torres 13. Barbara Lee 36. Raul Ruiz 14. Jackie Speier 37. Karen Bass 15. Eric Swalwell 38. Linda T. Sa´nchez 16. Jim Costa 39. Gilbert Ray Cisneros, Jr. 17. Ro Khanna 40. Lucille Roybal-Allard 18. -

May 11, 2020 the Honorable Nancy Pelosi the Honorable Kevin

May 11, 2020 The Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Honorable Kevin McCarthy Speaker Minority Leader U.S. House of Representatives U.S. House of Representatives Washington, D.C. 20515 Washington, D.C. 20515 Dear Speaker Pelosi and Leader McCarthy, We are writing in support of the calls for a $49.95 billion infusion of federal funding to state departments of Transportation (DOTs) in the next COVID-19 response legislation. Our transportation system is essential to America’s economic recovery, but it is facing an immediate need as the COVID-19 pandemic significantly impacts states’ transportation revenues. With negotiations for the next COVID-19 relief package underway, we write to convey our strong support that future legislation includes a provision to address the needs of highway and bridge projects. With millions of Americans following “stay-at-home” orders, many state governments are facing losses in revenues across the board. These State DOTs are not exempt from these losses but operate with unique funding circumstances by having their own revenue shortfalls. Projections are showing decreases in state motor fuel tax and toll receipts as vehicle traffic declines by 50 percent in most parts of the country due to work and travel restrictions. An estimated 30 percent average decline in state DOTs’ revenue is forecasted over the next 18 months. Some state DOTs could experience losses as high as 45 percent. Due to these grim realities, some states are unable to make contract commitments for basic operations such as salt and sand purchases for winter operations. Both short-term and long-term transportation projects that were previously set to move forward are being delayed, putting construction jobs at risk.