Lunar and Planetary Information Bulletin, Issues 121/122

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 1998 Gems & Gemology

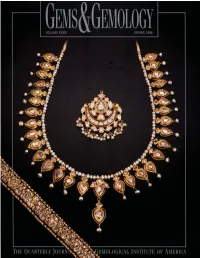

VOLUME 34 NO. 1 SPRING 1998 TABLE OF CONTENTS EDITORIAL 1 The Dr. Edward J. Gübelin Most Valuable Article Award FEATURE ARTICLE 4 The Rise to pProminence of the Modern Diamond Cutting Industry in India Menahem Sevdermish, Alan R. Miciak, and Alfred A. Levinson pg. 7 NOTES AND NEW TECHNIQUES 24 Leigha: The Creation of a Three-Dimensional Intarsia Sculpture Arthur Lee Anderson 34 Russian Synthetic Pink Quartz Vladimir S. Balitsky, Irina B. Makhina, Vadim I. Prygov, Anatolii A. Mar’in, Alexandr G. Emel’chenko, Emmanuel Fritsch, Shane F. McClure, Lu Taijing, Dino DeGhionno, John I. Koivula, and James E. Shigley REGULAR FEATURES pg. 30 44 Gem Trade Lab Notes 50 Gem News 64 Gems & Gemology Challenge 66 Book Reviews 68 Gemological Abstracts ABOUT THE COVER: Over the past 30 years, India has emerged as the dominant sup- plier of small cut diamonds for the world market. Today, nearly 70% by weight of the diamonds polished worldwide come from India. The feature article in this issue discuss- es India’s near-monopoly of the cut diamond industry, and reviews India’s impact on the worldwide diamond trade. The availability of an enormous amount of small, low-cost pg. 42 Indian diamonds has recently spawned a growing jewelry manufacturing sector in India. However, the Indian diamond jewelery–making tradition has been around much longer, pg. 46 as shown by the 19th century necklace (39.0 cm long), pendant (4.5 cm high), and bracelet (17.5 cm long) on the cover. The necklace contains 31 table-cut diamond panels, with enamels and freshwater pearls. -

The Rovers' Tale

Vol 436|11 August 2005 BOOKS & ARTS The rovers’ tale How NASA scientists overcame the odds to find signs of water on Mars. Roving Mars: Spirit, Opportunity, and the Exploration of the Red Planet by Steve Squyres JPL/NASA Hyperion: 2005. 432 pp. $25.95 Gregory Benford Roving Marsis a deftly and dramatically writ- ten history of the Mars rovers, Spirit and Opportunity. It is also a primer on how to do exotic geology at a distance of 100 million miles using robots. Steve Squyres knows how to render scenes and intricate technical detail to build tension, without losing sight of the thrill and grind of the groundbreaking work. “Eleven years had passed since I had started trying to send hardware to Mars, and in all that time I hadn’t seen a single plan for Mars explo- ration survive for more than about eighteen months before there was some sort of cata- clysm,” writes Squyres. Chief among these was the loss of the 1999 Mars Climate Orbiter: “The Mars program had become so screwed up that nobody had caught a high-school mis- take like mixing up English and metric units.” NASA doesn’t escape criticism over the rover mission either. According to Squyres, NASA’s On a roll: during testing for manoeuvrability in the lab, the rovers overcame a series of obstacles. rules meant that “cutting corners and taking chances” were the Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s The team had to trim experiments and patch signs of ancient surface water and found it, only management tools. After the losses of the problems right up to the launch date. -

The Richard B. Kershner Space Integration and Test Facility

ALVIN G. BUSH, WILLIAM E. FRAIN, and ALBERT C. REYMANN THE RICHARD B. KERSHNER SPACE INTEGRATION AND TEST FACILITY This article describes the functional characteristics and capabilities of the APL Space Integration and Test Facility. Its design was begun in late 1981, and the building was dedicated on October 11, 1983. INTRODUCTION The Richard B. Kershner Space Integration and Test Facility (Fig. 1) provides laboratory and office space to support the assembly and testing of spacecraft and spacecraft-borne instruments. Environmental test fa cilities within its 79,000 square feet simulate the rigors of launch and of operations in the vacuum conditions of space. The building contains assembly and test rooms that are clean enough so that precision optical equipment will not be contaminated; laboratories for the development of components for attitude control systems, power system electronics, batteries, and so lar arrays; reliability and quality assurance laborato Figure 1-The Richard B. Kershner building contains offices, ries for the inspection of delicate electronics parts and laboratories, and clean rooms. It is the point of final assem for failure analysis; and office space for 155 engineers, bly and qualification of spacecraft and space instrumentation. technicians, draftsmen, and secretaries. At the core of the building's function are areas devoted to the assembly and testing of spacecraft and Space allocation and layout (Fig. 2) were determined spacecraft instruments. Five rooms, each with 1000 by the requirement for the flow, under one roof, of square feet of floor space, adjoin a staging area served individual parts from a certified clean stockroom by an overhead crane. -

Planetary Report Report

The PLANETARYPLANETARY REPORT REPORT Volume XXIX Number 1 January/February 2009 Beyond The Moon From The Editor he Internet has transformed the way science is On the Cover: Tdone—even in the realm of “rocket science”— The United States has the opportunity to unify and inspire the and now anyone can make a real contribution, as world’s spacefaring nations to create a future brightened by long as you have the will to give your best. new goals, such as the human exploration of Mars and near- In this issue, you’ll read about a group of amateurs Earth asteroids. Inset: American astronaut Peggy A. Whitson who are helping professional researchers explore and Russian cosmonaut Yuri I. Malenchenko try out training Mars online, encouraged by Mars Exploration versions of Russian Orlan spacesuits. Background: The High Rovers Project Scientist Steve Squyres and Plane- Resolution Camera on Mars Express took this snapshot of tary Society President Jim Bell (who is also head Candor Chasma, a valley in the northern part of Valles of the rovers’ Pancam team.) Marineris, on July 6, 2006. Images: Gagarin Cosmonaut Training This new Internet-enabled fun is not the first, Center. Background: ESA nor will it be the only, way people can participate in planetary exploration. The Planetary Society has been encouraging our members to contribute Background: their minds and energy to science since 1984, A dust storm blurs the sky above a volcanic caldera in this image when the Pallas Project helped to determine the taken by the Mars Color Imager on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter shape of a main-belt asteroid. -

Boo-Hooray Catalog #10: Flyers

Catalog 10 Flyers + Boo-hooray May 2021 22 eldridge boo-hooray.com New york ny Boo-Hooray Catalog #10: Flyers Boo-Hooray is proud to present our tenth antiquarian catalog, exploring the ephemeral nature of the flyer. We love marginal scraps of paper that become important artifacts of historical import decades later. In this catalog of flyers, we celebrate phenomenal throwaway pieces of paper in music, art, poetry, film, and activism. Readers will find rare flyers for underground films by Kenneth Anger, Jack Smith, and Andy Warhol; incredible early hip-hop flyers designed by Buddy Esquire and others; and punk artifacts of Crass, the Sex Pistols, the Clash, and the underground Austin scene. Also included are scarce protest flyers and examples of mutual aid in the 20th Century, such as a flyer from Angela Davis speaking in Harlem only months after being found not guilty for the kidnapping and murder of a judge, and a remarkably illustrated flyer from a free nursery in the Lower East Side. For over a decade, Boo-Hooray has been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections and look forward to inviting you back to our gallery in Manhattan’s Chinatown. Catalog prepared by Evan Neuhausen, Archivist & Rare Book Cataloger and Daylon Orr, Executive Director & Rare Book Specialist; with Beth Rudig, Director of Archives. Photography by Evan, Beth and Daylon. -

OPENING CEREMONY 9:00 A.M

81st Annual Meeting of The Meteoritical Society 2018 (LPI Contrib. No. 2067) sess201.pdf Monday, July 23, 2018 OPENING CEREMONY 9:00 a.m. Concert Hall of the Academy of Science Building 9:00 a.m. Opening Ceremony Marina Ivanova, Vernadsky Institute, Convener for 81st Annual Meeting of The Meteoritical Society Eric Galimov, Vernadsky Institute, Scientific Advisor Dmitry Badyukov, Vernadsky Institute, Head of the Meteoritics Laboratory AWARD CEREMONY 9:30 a.m. Concert Hall of the Academy of Science Building Chairs: Trevor Ireland Meenakshi Wadhwa 9:30 a.m. Leonard Medal Recipient: Alexander N. Krot Citation: Kevin D. McKeegan The Leonard Medal is given to individuals who have made outstanding original contributions to the science of meteoritics or closely allied fields. The Meteoritical Society recognizes Alexander “Sasha” Krot with its 2018 Leonard Medal in recognition of his fundamental contributions to understanding the role oxygen isotopes in early solar system processes and aqueous alteration processes on asteroids. 9:45 a.m. Barringer Medal Recipient: Thomas Kenkmann Citation: Kai Wünnemann The Barringer Medal is given for outstanding work in the field of impact crating. The 2018 Barringer Medal is awarded to Professor Thomas Kenkmann for his fundamental contributions to our understanding of the structure mechanics and tectonics of rock displacement associated with the formation of hypervelocity impact craters. 10:00 a.m. Nier Prize Recipient: Lydia Hallis Citation: Martin Lee The Nier Prize is given for significant research in the field of meteoritics and closely related fields by a young scientist under the age of 35. The Meteoritical Society recognizes Lydia Hallis with its 2018 Nier Prize for her contributions to the understanding of the origin of volatiles in planets. -

A European Cooperation Programme

Year 32 • Issue #363 • July/August 2019 2,10 € ESPAÑOLA DE InternationalFirst Edition Defence of the REVISTA DEFEandNS SecurityFEINDEF ExhibitionA Future air combat system A EUROPEAN COOPERATION PROGRAMME BALTOPS 2019 Spain takes part with three vessels and a landing force in NATO’s biggest annual manoeuvres in the Baltic Sea ESPAÑOLA REVISTA DE DEFENSA We talk about defense NOW ALSO IN ENGLISH MANCHETA-INGLÉS-353 16/7/19 08:33 Página 1 CONTENTS Managing Editor: Yolanda Rodríguez Vidales. Editor in Chief: Víctor Hernández Martínez. Heads of section. Internacional: Rosa Ruiz Fernández. Director de Arte: Rafael Navarro. Parlamento y Opinión: Santiago Fernández del Vado. Cultura: Esther P. Martínez. Fotografía: Pepe Díaz. Sections. Nacional: Elena Tarilonte. Fuerzas Armadas: José Luis Expósito Montero. Fotografía y Archivo: Hélène Gicquel Pasquier. Maque- tación: Eduardo Fernández Salvador. Collaborators: Juan Pons. Fotografías: Air- bus, Armada, Dassault Aviation, Joaquín Garat, Iñaki Gómez, Latvian Army, Latvian Ministry of Defence, NASA, Ricardo Pérez, INDUSTRY AND TECHNOLOGY Jesús de los Reyes y US Navy. Translators: Grainne Mary Gahan, Manuel Gómez Pumares, María Sarandeses Fernández-Santa Eulalia y NGWS, Fuensanta Zaballa Gómez. a European cooperation project Germany, France and Spain join together to build the future 6 fighter aircraft. Published by: Ministerio de Defensa. Editing: C/ San Nicolás, 11. 28013 MADRID. Phone Numbers: 91 516 04 31/19 (dirección), 91 516 04 17/91 516 04 21 (redacción). Fax: 91 516 04 18. Correo electrónico:[email protected] def.es. Website: www.defensa.gob.es. Admi- ARMED FORCES nistration, distribution and subscriptions: Subdirección General de Publicaciones y 16 High-readiness Patrimonio Cultural: C/ Camino de Ingenieros, 6. -

Curriculum Vitae

DANTE S. LAURETTA Lunar and Planetary Laboratory Department of Planetary Sciences University of Arizona Tucson, AZ 85721-0092 Cell: (520) 609-2088 Email: [email protected] CHRONOLOGY OF EDUCATION Washington University, St. Louis, MO Dept. of Earth and Planetary Sciences Ph.D. in Earth and Planetary Sciences, 1997 Thesis: Theoretical and Experimental Studies of Fe-Ni-S, Be, and B Cosmochemistry Advisor: Bruce Fegley, Jr. University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ Depts. of Physics, Mathematics, and East Asian Studies B.S. in Physics and Mathematics, Cum Laude, 1993 B.A. in Oriental Studies (emphasis: Japanese), Cum Laude, 1993 CHRONOLOGY OF EMPLOYMENT Professor, Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, Dept. of Planetary Sciences, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ; 2012 – present. Principal Investigator, OSIRIS-REx Asteroid Sample Return Mission, NASA New Frontiers Program, 2011 – present. Deputy Principal Investigator, OSIRIS-REx Asteroid Sample Return Mission, NASA New Frontiers Program, 2008 – 2011. Associate Professor, Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, Dept. of Planetary Sciences, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ; 2006 – 2012. Assistant Professor, Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, Dept. of Planetary Sciences, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ; 2001 – 2006. Associate Research Scientist, Dept. of Chemistry & Biochemistry, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ; 1999 – 2001. Postdoctoral Research Associate, Dept. of Geology, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ Primary project: Transmission electron microscopy of meteoritic minerals. Supervisor: Peter R. Buseck; Dates: 1997 – 1999. Research Assistant, Dept. of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Washington Univ., St. Louis, MO Primary project: Experimental studies of sulfide formation in the solar nebula. Advisor: Bruce Fegley, Jr.; Dates: 1993 – 1997. Research Intern, NASA Undergraduate Research Program, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ Primary project: Development of a logic-based language for S.E.T.I. -

Masculinism, Resistance, and Recognition in Vietnam

NORMA International Journal for Masculinity Studies ISSN: 1890-2138 (Print) 1890-2146 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rnor20 Recognising shadows: masculinism, resistance, and recognition in Vietnam Paul Horton To cite this article: Paul Horton (2019): Recognising shadows: masculinism, resistance, and recognition in Vietnam, NORMA, DOI: 10.1080/18902138.2019.1565166 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/18902138.2019.1565166 © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 11 Jan 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 110 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rnor20 NORMA: INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR MASCULINITY STUDIES https://doi.org/10.1080/18902138.2019.1565166 Recognising shadows: masculinism, resistance, and recognition in Vietnam Paul Horton Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Pride parades, LGBT rights demonstrations, and revisions to the Received 9 July 2017 Marriage and Family Law highlight the extent to which norms and Accepted 12 November 2018 values related to gender, sexuality, marriage, and the family have KEYWORDS recently been challenged in Vietnam. They also illuminate the Vietnam; LGBT; masculinism; gendered power relations being played out in the socio-cultural recognition; power; context of Vietnam, and thus open up for a more in-depth resistance consideration of the ways in which LGBT people have experienced and resisted these relations in everyday life. Drawing on ethnographic fieldwork conducted in Vietnam’s two largest cities, Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, in 2012, this article discusses the relations between these power relations, the dominant Vietnamese discourse of masculinity, or masculinism, and the politics of recognition. -

Pro.Ffress D &Dentsdc Raddo

Pro.ffress d_ &dentSdc Raddo FIFTEENTH GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF THE INTERNATIONAL SCIENTIFIC RADIO UNION September 5-15, 1966 Munich, Germany REPORT OF THE U.S.A. NATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE INTERNATIONAL SCIENTIFIC RADIO UNION Publication 1468 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL Washington, D.C. 1966 Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 55-31605 Available from Printing and Publishing Office National Academy of Sciences 2101 Constitution Avenue Washington, D.C. 20418 Price: $10.00 October28,1966 Dear Dr. Seitz: I ampleasedto transmitherewitha full report to the NationalAcademy of Sciences--NationalResearchCouncil,onthe 15thGeneralAssemblyof URSIwhichwasheldin Munich,September5-15, 1966. TheUnitedStatesNationalCommitteeof URSIhasparticipatedin the affairs of the Unionfor forty-five years. It hashadmuchinfluenceonthe Unionas,.for example,in therecent creationof a Commissiononthe Mag- netosphere.ThisnewCommission,whichis nowvery strong,demonstrates the ability of theUnion,oneof ICSU'sthree oldest,to respondto the changingneedsof its field. AlthoughtheUnitedStatessendsthelargest delegationsof anycountry to the GeneralAssembliesof URSI,theyare neverthelessrelatively small becauseof thestrict mannerin whichURSIcontrolsthe size of its Assem- blies. This is donein order to preventineffectivenessthroughuncontrolled participationbyvery largenumbersof delegates.Accordingly,our delega- tions are carefully selected,andcomprisepeoplequalifiedto prepareand presentour NationalReportto the Assembly.Thepre-Assemblyreport is a report of progressin -

Mighty Eagle: the Development and Flight Testing of an Autonomous Robotic Lander Test Bed

Mighty Eagle: The Development and Flight Testing of an Autonomous Robotic Lander Test Bed Timothy G. McGee, David A. Artis, Timothy J. Cole, Douglas A. Eng, Cheryl L. B. Reed, Michael R. Hannan, D. Greg Chavers, Logan D. Kennedy, Joshua M. Moore, and Cynthia D. Stemple PL and the Marshall Space Flight Center have been work- ing together since 2005 to develop technologies and mission concepts for a new generation of small, versa- tile robotic landers to land on airless bodies, including the moon and asteroids, in our solar system. As part of this larger effort, APL and the Marshall Space Flight Center worked with the Von Braun Center for Science and Innovation to construct a prototype monopropellant-fueled robotic lander that has been given the name Mighty Eagle. This article provides an overview of the lander’s architecture; describes the guidance, navi- gation, and control system that was developed at APL; and summarizes the flight test program of this autonomous vehicle. INTRODUCTION/PROJECT BACKGROUND APL and the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) technology risk-reduction efforts, illustrated in Fig. 1, have been working together since 2005 to develop have been performed to explore technologies to enable technologies and mission concepts for a new genera- low-cost missions. tion of small, autonomous robotic landers to land on As part of this larger effort, MSFC and APL also airless bodies, including the moon and asteroids, in our worked with the Von Braun Center for Science and solar system.1–9 This risk-reduction effort is part of the Innovation (VCSI) and several subcontractors to con- Robotic Lunar Lander Development Project (RLLDP) struct the Mighty Eagle, a prototype monopropellant- that is directed by NASA’s Planetary Science Division, fueled robotic lander. -

Naretha Meteorite (Synonyms Kingoonya, Kingooya)

Rec. West. Aust. Mus., 1976, 4 (1) NARETHA METEORITE (Sync;>nyms: Kingoonya, Kingooya) W.H. CLEVERLY* [Received 27 May 1975. Accepted 1 October 1975. Published 31 August 1976.1 ABSTRACT Much of the missing portion of the Naretha (Western Australia) meteorite has been located in museums as an un-named specimen and as two smaller specimens masquerading under the name 'Kingoonya' (or 'Kingooya'). The use of the junior synonyms with their implications of a South Australian site of find should be discontinued. INTRODUCfION Naretha meteorite, an L4 chondrite, was found in 1915 about 3 km north of the 205-mile station during construction of the Trans-Australian Railway. It was broken into at least three major pieces which were acquired by Mr John Darbyshire, Supervising Engineer for the construction of the western end of the railway (construction was proceeding simultaneously from both Kalgoorlie and Port Augusta ends - Fig. 1). Mr Darbyshire donated the meteorite to the W.A. School of Mines in Kalgoorlie where one' piece was retained and exhibited with a photograph of the reassembled meteorite (Fig. 2). A second fragment which was passed on to the Geological Survey of Western Australia was noted briefly by Simpson (1922) who first used the name 'Naretha', the name which had been given to the 205-mile station. There is strong presumptive evidence that the third fragment was passed on to Mr S.F.C. Cook of Kalgoorlie, a private collector from whose inaccurate verbal statements and undocumented collection, the subsequent confusion arose. In late 1926 Mr Cook gave a small piece of 'meteorite to Mr G.W.