The Modernization of Prince Edward Island Under the Government of WR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From the Ground up the First Fifty Years of Mccain Foods

CHAPTER TITLE i From the Ground up the FirSt FiFty yearS oF mcCain FoodS daniel StoFFman In collaboratI on wI th t ony van l eersum ii FROM THE GROUND UP CHAPTER TITLE iii ContentS Produced on the occasion of its 50th anniversary Copyright © McCain Foods Limited 2007 Foreword by Wallace McCain / x by All rights reserved. No part of this book, including images, illustrations, photographs, mcCain FoodS limited logos, text, etc. may be reproduced, modified, copied or transmitted in any form or used BCE Place for commercial purposes without the prior written permission of McCain Foods Limited, Preface by Janice Wismer / xii 181 Bay Street, Suite 3600 or, in the case of reprographic copying, a license from Access Copyright, the Canadian Toronto, Ontario, Canada Copyright Licensing Agency, One Yonge Street, Suite 1900, Toronto, Ontario, M6B 3A9. M5J 2T3 Chapter One the beGinninG / 1 www.mccain.com 416-955-1700 LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION Stoffman, Daniel Chapter Two CroSSinG the atlantiC / 39 From the ground up : the first fifty years of McCain Foods / Daniel Stoffman For copies of this book, please contact: in collaboration with Tony van Leersum. McCain Foods Limited, Chapter Three aCroSS the Channel / 69 Director, Communications, Includes index. at [email protected] ISBN: 978-0-9783720-0-2 Chapter Four down under / 103 or at the address above 1. McCain Foods Limited – History. 2. McCain, Wallace, 1930– . 3. McCain, H. Harrison, 1927–2004. I. Van Leersum, Tony, 1935– . II. McCain Foods Limited Chapter Five the home Front / 125 This book was printed on paper containing III. -

Provincial Solidarities: a History of the New Brunswick Federation of Labour

provincial solidarities Working Canadians: Books from the cclh Series editors: Alvin Finkel and Greg Kealey The Canadian Committee on Labour History is Canada’s organization of historians and other scholars interested in the study of the lives and struggles of working people throughout Canada’s past. Since 1976, the cclh has published Labour / Le Travail, Canada’s pre-eminent scholarly journal of labour studies. It also publishes books, now in conjunction with AU Press, that focus on the history of Canada’s working people and their organizations. The emphasis in this series is on materials that are accessible to labour audiences as well as university audiences rather than simply on scholarly studies in the labour area. This includes documentary collections, oral histories, autobiographies, biographies, and provincial and local labour movement histories with a popular bent. series titles Champagne and Meatballs: Adventures of a Canadian Communist Bert Whyte, edited and with an introduction by Larry Hannant Working People in Alberta: A History Alvin Finkel, with contributions by Jason Foster, Winston Gereluk, Jennifer Kelly and Dan Cui, James Muir, Joan Schiebelbein, Jim Selby, and Eric Strikwerda Union Power: Solidarity and Struggle in Niagara Carmela Patrias and Larry Savage The Wages of Relief: Cities and the Unemployed in Prairie Canada, 1929–39 Eric Strikwerda Provincial Solidarities: A History of the New Brunswick Federation of Labour / Solidarités provinciales: Histoire de la Fédération des travailleurs et travailleuses du Nouveau-Brunswick David Frank A History of the New Brunswick Federation of Labour david fra nk canadian committee on labour history Copyright © 2013 David Frank Published by AU Press, Athabasca University 1200, 10011 – 109 Street, Edmonton, ab t5j 3s8 isbn 978-1-927356-23-4 (print) 978-1-927356-24-1 (pdf) 978-1-927356-25-8 (epub) A volume in Working Canadians: Books from the cclh issn 1925-1831 (print) 1925-184x (digital) Cover and interior design by Natalie Olsen, Kisscut Design. -

Prince Edward Island and the 1971 National Farmers Union Highway Demonstration Ryan O’Connor

Document generated on 10/01/2021 5:07 a.m. Acadiensis Agrarian Protest and Provincial Politics: Prince Edward Island and the 1971 National Farmers Union Highway Demonstration Ryan O’Connor Volume 37, Number 1, Winter 2008 Article abstract During ten days in August 1971 Prince Edward Island farmers, led by the local URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/acad37_1art02 chapter of the National Farmers Union, staged high-profile public protests against the provincial government’s neglect of family farm issues and its See table of contents promotion of economic rationalization and modernization as exemplified in the government’s 1969 Comprehensive Development Plan. While these protests did not stop the trend towards farm abandonment, they did manage to put the Publisher(s) concerns of small farmers on the political agenda and dampen the government’s enthusiasm for development planning that ignored small The Department of History at the University of New Brunswick producers. The result was a consultation process between the government and small farmers and the government’s 1972 Family Farm Development Policy. ISSN 0044-5851 (print) 1712-7432 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article O’Connor, R. (2008). Agrarian Protest and Provincial Politics: Prince Edward Island and the 1971 National Farmers Union Highway Demonstration. Acadiensis, 37(1), 31–55. All rights reserved © Department of History at the University of New This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit Brunswick, 2008 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. -

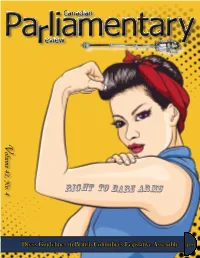

Ar Ba to Rig Re Ht Ms

Canadian eview V olume 42, No. 4 Right to BaRe Arms Dress Guidelines in British Columbia’s Legislative Assembly p. 6 2 CANADIAN PARLIAMENTARY REVIEW/SUMMER 2019 There are many examples of family members sitting in parliaments at the same time. However, the first father-daughter team to sit together in a legislative assembly did not happen in Canada until 1996. That is when Sue Edelman was elected to the 29th Yukon Legislative Assembly, joining her re-elected father, Ivan John “Jack” Cable. Mr. Cable moved to the North in 1970 after obtaining degrees in Chemical Engineering, a Master’s in Business Administration and a Bachelor of Laws in Ontario. He practiced law in Whitehorse for 21 years, and went on to serve as President of the Yukon Chamber of Commerce, President of the Yukon Energy Corporation and Director of the Northern Canada Power Commission. He is also a founding member of the Recycle Organics Together Society and the Boreal Alternate Energy Centre. Mr. Cable’s entry into electoral politics came in 1992, when he successfully won the riding of Riverdale in East Whitehorse to take his seat in the Yukon Legislative Assembly. Ms. Edelman’s political presence had already been established by the time her father began his term as an MLA. In 1988, she became a Whitehorse city councillor, a position she held until 1994. In her 1991 reelection, she received more votes for her council seat than mayor Bill Weigand received. Following her time on city council, she was elected to the Selkirk Elementary School council. In the 1996 territorial election, she ran and won in the Riverdale South riding. -

CALHOUN, JOHN R., Merchant; B. in New Brunswick. Calhoun, a Liberal

Calk'It'///! Callbeck and Ruth Campbell; United. Callbeck, a Liberal, was first elected to the Legislative Assembly in the general election of 1974 for 4'1' Prince. She was re-elected in the general elec tion of 1993 for 1" Queens. She served as Minister of Health and Social Services and Minister Respon c sible for the Disabled from 1974 to 1978. In the federal election of 1988, Callbeck was elected to the House of Commons as the representative for CALHOUN, JOHN R., merchant; b. in Malpeque and remained there until 1993 when she New Brunswick. resigned her seat to seek the leadership of the Prince Calhoun, a Liberal, was elected to the House Edward Island Liberal Party. While in Ottawa she of Assembly in the 1876 general election for 4,h served as the Official Opposition critic for con Prince. He served on several committees, includ sumer and corporate affairs, energy, mines and re ing the Public Accounts Committee. Calhoun sources, and financial institutions, and as the asso chaired the Special Committee to Report Standing ciate critic for privatization and regulatory affairs. Rules and Orders for the governance of the House Callbeck was the vice-chair of the Caucus Com of Assembly. In 1877 he presented a petition to mittee on Sustainable Development. In 1993 she the House on behalf of the citizens of Summerside, returned to the provincial scene, becoming Liberal which stated that the Act for the Better Govern leader on 23 January 1993 upon the resignation of ment of Towns and Villages was inadequate. The Premier Joseph Ghiz'". -

Catherinehennessey.Com February 29, 2000 to July 9, 2003 Copyright © Catherine Hennessey, 2008

CatherineHennessey.com February 29, 2000 to July 9, 2003 Copyright © Catherine Hennessey, 2008. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying (except for the intended purpose if stated within the document), microfilm, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the author. Edited by Peter Rukavina. This is a reproduction of posts on the CatherineHennessey.com weblog made from February 29, 2000 to July 9, 2003. Posts are reproduced in their entirety as they appeared online, with the exception of minor corrections to spelling and punctuation. Posts related exclusively to the weblog itself, or consisting entirely of web links, have been removed. Catherine Hennessey 222 Sydney Street Charlotte Town, Prince Edward Island C1A 1G8 http://catherinehennessey.com/ [email protected] Table of Contents Editor’s Note.................................................................................. 9 This is an introduction.................................................................. 10 Downtown Residents Meeting..................................................... 10 A Thought.................................................................................... 10 My main cause............................................................................. 10 The Furnishings of 19th Century Prince Edward Island.............. 12 Prince Edward Island Museum and Heritage Foundation.......... -

ROYAL GAZETTE January 5, 2019

Prince Edward Island PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY VOL. CXLV – NO. 1 Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, January 5, 2019 CANADA PROVINCE OF PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND IN THE SUPREME COURT - ESTATES DIVISION TAKE NOTICE that all persons indebted to the following estates must make payment to the personal representative of the estates noted below, and that all persons having any demands upon the following estates must present such demands to the representative within six months of the date of the advertisement: Estate of: Personal Representative: Date of Executor/Executrix (Ex) Place of the Advertisement Administrator/Administratrix (Ad) Payment FERRON, Joseph Arthur Janine Sheehan (EX.) Allen J. MacPhee Law Corp. (also known as Arthur Ferron) 106 Main Street Souris Souris, PE Kings Co., PE January 5, 2019 (1 – 14)* MOLLINS, Vincent (also known Norman LaLonde (EX.) Carr, Stevenson & MacKay as Charles Vincent Mollins) Carolyn LaLonde (EX.) 65 Queen Street Hartsville Charlottetown, PE Queens Co., PE January 5, 2019 (1 – 14)* MacDONALD, Florence Margaret Lisa M. Wells (EX.) Allen J. MacPhee Law Corp. (also known as Florence MacDonald) 106 Main Street Souris River Souris, PE Kings Co., PE January 5, 2019 (1 – 14)* MacLEAN, John Wayne Tracey Lynn MacLean (EX.) Carr, Stevenson & MacKay Cornwall 65 Queen Street Queens Co., PE Charlottetown, PE January 5, 2019 (1 – 14)* SCHILLER, Edward Suzanne LaPorte (EX.) Cox & Palmer Vaudreuil-Dorion 97 Queen Street Quebec Charlottetown, PE January 5, 2019 (1 – 14)* *Indicates date of first publication in the Royal Gazette. -

Annual Report 2018

Literacy opens doors Thank you to all our supporters! Special Thank You this year goes to: Province of PEI For providing operational funding 2017/2018 Annual Report April 1, 2017 to March 31, 2018 Our Vision All Islanders are able to participate fully in their family, work, and community Our Mission To advance literacy for the people of Prince Edward Literacy opens doors Island 28 years helping Islanders improve their literacy skills Our Belief Building a culture of literacy and learning supports all Islanders to reach their full potential and helps build a better future for all Member Organizations Member Organizations Chairperson’s Message Friends of Literacy, Canadian Mental Health Association PEI Association for Community Living For nearly 30 years, the PEI Literacy Alliance has been Canadian Union of Public Employees PEI Association for Newcomers to Canada helping Islanders of all ages to acquire essential literacy (CUPE) skills. PEI Business Women's Association CHANCES Family Centre While the organization has a wonderful legacy, there is PEI Council of People with Disabilities still significant work to be done. Over 40% of Prince Collège du l'î le Edward Islanders still struggle with literacy in some PEI Family Violence Prevention Services form, be that reading, writing or numeracy. Community Legal Information PEI Federation of Labour Association The PEI Literacy Alliance's commitment to advocating for and supporting these Islanders, particularly the children, remains steadfast. PEI Home and School Federation Creative PEI (formerly Culture PEI) We know that improving literacy levels is the key to a safer, healthier and more PEI Professional Librarian's Association Department of Education, Early Years prosperous Island community. -

Fathers of Confederation Buildings Trust Contents

2018-2019 ANNUAL REPORT FATHERS OF CONFEDERATION BUILDINGS TRUST CONTENTS OUR PROGRAMS SUPPORTING ROLES 4 Theatre 12 Marketing 15 Foundation 6 Gallery 13 Development 16 Financial Statements 9 French Programming 13 Sponsorship 10 Arts Education and Heritage 14 Founders’ Circle MESSAGE FROM THE CEO AND CHAIR Confederation Centre of the Arts is moving through an exciting period of change and renewal. During these past 12 months we have completed a new strategic plan, Connecting through the arts . We have welcomed new people into leadership roles at the Centre and on the Board of Directors. We have streamlined business processes and updated tools to support board governance and communications. We have worked hard to improve employee engagement and staff communication, and we’ve invested in new technology and strate- gic planning to improve reporting and communication with our members, donors, and other supporters. In the fall of 2019, we will launch a renewed membership program with more ways for community members to engage with Confederation Centre of the Arts. The 2019-24 Strategic Plan builds on the successes of the previous five years while providing clarity for a renewed way forward. As Canada moves ahead and Canadian identity evolves, we too have the responsi- bility to evolve with it, reflecting that changing identity through engaging programming. After a thorough and inclusive strategic planning process, we have set many goals and priorities for the next five years, and organized those priorities around three pillars: Artistic Excellence, Engaged Diverse Communities, and 2018-19 Organizational Sustainability. The Centre has continued its tradition of Artistic Excellence through the outstanding work that appears in the gallery, on stage, and in our classrooms. -

ROYAL GAZETTE January 16, 2016

Prince Edward Island Postage paid in cash at First Class Rates PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY VOL. CXLII – NO. 3 Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, January 16, 2016 CANADA PROVINCE OF PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND IN THE SUPREME COURT - ESTATES DIVISION TAKE NOTICE that all persons indebted to the following estates must make payment to the personal representative of the estates noted below, and that all persons having any demands upon the following estates must present such demands to the representative within six months of the date of the advertisement: Estate of: Personal Representative: Date of Executor/Executrix (Ex) Place of the Advertisement Administrator/Administratrix (Ad) Payment BELL, Olive Grace Christine Jackson (EX.) Cox & Palmer Beach Point 4A Riverside Dr. Kings Co., PE Montague, PE January 16, 2016 (3-16)* FRASER, George Edward June Fraser (EX.) Allen J. MacPhee Law St. Margarets Corporation Kings Co., PE 106 Main Street January 16, 2016 (3-16)* Souris, PE LECKY, Allan James (also Kenneth Lecky (EX.) Cox & Palmer known as Allen James Lecky) 250 Water Street Summerside Summerside, PE Prince Co., PE January 16, 2016 (3-16)* MacINTYRE, Ronald J. Yvonne Irwin-Keene (EX.) Carr Stevenson & MacKay Monticello, County of Aroostook 65 Queen Street Maine, USA Charlottetown, PE January 16, 2016 (3-16)* MacKAY, Edith Helene Emmett Doyle Carr Stevenson & MacKay Charlottetown Zelda Doyle (EX.) 65 Queen Street Queens Co., PE Charlottetown, PE January 16, 2016 (3-16)* *Indicates date of first publication in the Royal Gazette. This is the official version -

Lyrical Prelude

Alex B. Campbell Lyrical Prelude chapter two “The Child is father of the Man” William Wordsworth, The Rainbow, 1802 Lyrical Prelude ‘ ‘ Alex was a very inclusive kind of guy, right from the word go. People who know Alex Campbell intimately describe him in consistent terms. When asked about her husband’s character, Marilyn Campbell points to his Ken Grant, teenage friend of Alex Campbell “outgoing personality”, his “easy way with people” and his “sense of humour.” She adds that Alex “sometimes carries that a little too far with his practical jokes.”1 Campbell’s sisters Virginia and Harriet say their brother, whom they ‘‘ knew as “Sander” while growing up, was “always very, very fair.” Referring to an early family photo, they say it shows their brother Mel to be “energetic” and Alex “attentive.”2 “We always called him ‘lucky.’ If he’s driving through the village and his boat trailer unhooks, he just slows down and it catches up. He was always ready for an open door.” Campbell’s first-born son Blair recalls boat trips and pranks at the family’s Stanley Bridge cottage. During Christmas retreats to “Stanley,” the children looked forward to the opportunity to speak to Santa over the CB radio. They giggled at the qualified promise: “We’ll see what Santa can do.”3 Alex Campbell’s boyhood friends describe him as good natured and quiet, more likely to be listening than speaking. “You knew that when Alex had something to say, you listened,” says Wyman Miller, who threw second stone on Campbell’s 1952 schoolboy championship curling team. -

LEONE,” Teacher; B

BAGNALL, JAMES “JIM” DOUGLAS, business owner; b. 15 February 1949 in Summerside, son of Harold Bagnall and Charlotte Muirhead; m. 16 September 1967 Eileen Craig of Victoria, and they have four children, Douglas Kent, Craig James, Tara Lee and Tanya; Presbyterian. Bagnall, a Progressive Conservative, was first elected to the Legislative Assembly in the 18 November 1996 general election for District 3 Montague‐Kilmuir. He was re‐elected in the general elections of 17 April 2000, 29 September 2003 and 28 May 2007. Bagnall retired undefeated from provincial politics prior to the 3 October 2011 general election. On 27 March 2006 he was appointed Minister of Agriculture, Fisheries and Aquaculture. Prior to his Cabinet appointment he served as Government Whip, Government House Leader, and chair of Government Caucus. He has also served as chair of the legislative review committee and as a member of the standing committees on agriculture, environment, energy and forestry; community and intergovernmental affairs; education and innovation; fisheries, transportation and rural development; health, social development and seniors; legislative management; privileges, rules and private bills; and Public Accounts. Bagnall served as interim leader of the opposition from 9 June to 2 October 2010. During his time in opposition he also worked as Opposition House Leader and opposition critic for the Provincial Treasury, agriculture, fisheries and aquaculture, tourism, environment and forestry. Bagnall attended primary school in Central Bedeque and graduated from Athena Regional High School in 1968. He went on to work in retail sales for more than 30 years, managing Stedman’s department store in Montague for a decade before purchasing it in 1985.