Picturing Problems: Solving Logic Puzzles Diagrammatically

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Circuit of Computer Science Unplugged Activities Based on the Life of Ada Lovelace

Circuit of Computer Science Unplugged activities based on the life of Ada Lovelace 1st Given Name Surname 2nd Given Name Surname 3rd Given Name Surname dept. name of organization (of Aff.) dept. name of organization (of Aff.) dept. name of organization (of Aff.) name of organization (of Aff.) name of organization (of Aff.) name of organization (of Aff.) City, Country City, Country City, Country email address email address email address Abstract—Ada Lovelace’s life is a source of inspiration for defining what are the highest priority tasks and iv) create women and men of all ages, for being a bright-minded and algorithms to solve them. visionary person. His greatest achievement was to have written Unplugged computing occurs through playful activities, the first computer program in history. This article presents a methodological proposal for didactic use of a children’s book group dynamics, and material elaboration. Bell et al. (2015) about Ada Lovelace by proposing a circuit of unplugged activities have been concerned with solving issues that can arise as soon in order to refine the computational thinking (CT) in children and as we are introduced to computing: how do computers work adolescents. This methodology was applied in a workshop during and what do computers solve? The book of such authors, titled the BLIND in the BLIND Conference. A quali-quantitative “CS unplugged: Computer Science without a Computer”, has analysis performed with participants indicates the suitability of the proposed methodology. many activities that can be reproduced with children in an easy Index Terms—computational thinking, cs unplugged, stem, and intuitive way. -

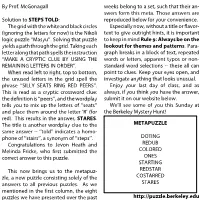

By Prof. Mcgonagall Solution to STEPS TOLD: the Grid with The

By Prof. McGonagall weeks belong to a set, such that their an- swers form this meta. Those answers are Solution to STEPS TOLD: reproduced below for your convenience. Thegridwiththewhiteandblackcircles Especially now, without a title or flavor- (ignoring the letters for now) is the Nikoli text to give outright hints, it is important logic puzzle ‘‘Masyu’’. Solving that puzzle to keep in mind Rule 9: Always be on the yieldsapaththroughthegrid. Takingeach lookout for themes and patterns. Para- letteralongthatpathspellstheinstruction graph breaks in a block of text, repeated ‘‘MAKE A CRYPTIC CLUE BY USING THE words or letters, apparent typos or non- REMAINING LETTERS IN ORDER’’. standard word selections -- these all can When read left to right, top to bottom, point to clues. Keep your eyes open, and the unused letters in the grid spell the investigate anything that looks unusual. phrase ‘‘SILLY SEATS RING RED PEERS’’. Enjoy your last day of class, and as This is read as a cryptic crossword clue: always, if you think you have the answer, the definition is ‘‘peers’’, and the wordplay submit it on our website below. tells you to mix up the letters of ‘‘seats’’ We’ll see some of you this Sunday at and place them around the letter ‘R’ (for the Berkeley Mystery Hunt! red). This results in the answer, STARES. The title is another wordplay clue to the METAPUZZLE same answer -- ‘‘told’’ indicates a homo- phone of ‘‘stairs’’, a synonym of ‘‘steps’’. DOTING Congratulations to Jevon Heath and REDUB Melinda Fricke, who first submitted the COLORED correct answer to this puzzle. ONES STARTING This now brings us to the metapuz- REDSTAR zle, a new puzzle consisting solely of the COSTARRED answers to all previous puzzles. -

Metrics for Better Puzzles 1 Introduction

Metrics for Better Puzzles Cameron Browne Computational Creativity Group Imperial College London [email protected] Abstract. While most chapters of this book deal with run-time telemetry observed from user data, we turn now to a different type of metric, namely design-time metrics for level generation. We describe Hour Maze, a new type of pure deduction puzzle, and outline methods for the automated generation and solution of lev- els. Solution involves a deductive search that estimates a level’s iterative and strategic depth. This information, together with sym- metry analysis of wall and hint distributions, provides useful met- rics with which levels may be classified and described. Results from a user survey indicate that players’ enjoyment of computer- designed levels may be affected by their perception of whether those levels are indeed computer-designed or handcrafted by hu- mans. We suggest ways in which puzzle metrics may be used to increase the perception of intelligence and personality behind level designs, to make them more interesting for players. Keywords. Logic puzzle; Hour Maze; Nikoli; deductive search; quality metrics; procedural content generation. 1 Introduction The current crop of smart phones and handheld game devices are the ideal plat- form for logic puzzles, which are enjoying a surge in popularity due to the main- stream success of titles such as Sudoku and Kakuro. Such puzzles can be played easily on small screens without losing any of their appeal, and can provide a deep, engaging playing experience while being conveniently short and self-contained. Fig. 1 shows a new logic puzzle called Hour Maze currently under develop- ment for iOS devices. -

Grade 7 & 8 Math Circles Logic Puzzles Introduction Strategies

Faculty of Mathematics Waterloo, Ontario N2L 3G1 Grade 7 & 8 Math Circles October 29/30, 2013 Logic Puzzles Introduction Mathematics isn't at all about memorizing formulas or doing procedures over and over. It's all about thinking logically, finding patterns and connections, and solving problems. A logic puzzle is a problem, challenge, or game that requires the player to use forms of critical thinking to arrive at a solution. Strategies Some tips to keep in mind when solving logic puzzles: • Read and reread the problem until you fully understand it and its goals. • Organize your information in a chart or diagram to focus only on relevant points. • Use logical reasoning to eliminate options. • Tackle simpler sub problems, but keep the big picture in mind. • List out all of the possibilities if you can, and use \guess and check". • Take it one step at a time. • Use a puzzle's rules and guidelines to double-check your work. • Be persistent. If you become stuck, remember that these problems are meant to be fun! The most important thing to remember when working on logic puzzles is that they are logical; every step has to make sense and be verifiable. 1 Sudoku The goal when filling out a sudoku is to enter a number from 1 to 9 in each box of the puzzle. Each row, column, and outlined 3 × 3 region must contain each number only once. Example I 2D-Sudoku Fill every row, columns, and shaded diagonal with the numbers from 1 to 5. Example II 2 Minesweeper Draw a mine in some cells of the grid. -

A Simple Solution to the Hardest Logic Puzzle Ever 105 11 Potts, C

a simple solution to the hardest logic puzzle ever 105 11 Potts, C. 2005. The Logic of Conventional Implicatures. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Searle, J. R. and D. Vanderveken. 1985. Foundations of Illocutionary Logic. Cam- bridge: Cambridge University Press. Zwicky, A. M. 1974. Hey, Whatsyourname! In Papers from the Tenth Regional Meeting, Chicago Linguistic Society, ed. M. W. LaGaly, R. A. Fox and A. Bruck. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society. A simple solution to the hardest logic puzzle ever Brian Rabern & Landon Rabern We present the simplest solution ever to ‘the hardest logic puzzle ever’. We then modify the puzzle to make it even harder and give a simple solution to the modified puzzle. The final sections investigate exploding god-heads and a two-question solution to the original puzzle. 1. The simplest solution to the ‘hard’ puzzle The puzzle. Three gods A, B, and C are called, in some order, ‘True’, ‘False’, and ‘Random’. True always speaks truly, False always speaks falsely, but whether Random speaks truly or falsely is a completely random matter. Your task is to determine the identities of A, B, and C by asking three yes-no questions; each question must be put to exactly one god. The gods understand English, but will answer all questions in their own lan- guage, in which the words for ‘yes’ and ‘no’ are ‘da’ and ‘ja’, in some order. You do not know which word means which.1 1 Boolos 1996: 62. The so-called ‘hardest logic puzzle ever’ is coined as such by George Boolos. Boolos credits the logician Raymond Smullyan as the originator of the puzzle and the computer scientist John McCarthy with adding the difficulty of not knowing what ‘da’ and ‘ja’ mean. -

Mathematical Games, Riddles, Questions, and Puzzles Have a Long History Going Back As Far As About 1800 BCE

History of Mathematical Games and Puzzles By: Amanda Kent Types of Puzzles History Early Egyptian Math - Number games - - Mathematical games, riddles, questions, and puzzles have a - Based largely on puzzle type problems. - Geometrical puzzles - long history going back as far as about 1800 BCE. Example: The Rhind Papyrus (1850 BCE) Network problems - - They can range from simple arithmetic or logic puzzles to Combinatorial Problems - complex problems which are still unsolved today. “Seven houses contain seven cats. Each cat kills seven mice. Each Etc. - Mathematical games and puzzles are all throughout the mouse had eaten seven ears of grain. Each ear of grain would have history of mathematics, some of which have led to the study produced seven hekats of wheat. What is the total of all of these?” of many areas of math. Solution: 71 +72 +73 +74 +75 = 7 + 49 + 343 + 2,401 + 16,807 = 19,607 The Tower of Hanoi Probability History of Magic Squares Created by Mr. Claus, Mandarin of the College of Li-Sou-Stian in 1883 - In the 17th century Fermat and Pascal were the first to take a The game consists of three pegs standing upright. Upon one of the pegs - The history of magic squares hasn't been serious look at probability. are a series of rings, decreasing in radius from bottom to top. (There are well researched and is very questionable and - Gambling had obviously existed for a long time before this, usually anywhere from 3 to 8 rings, with the original game possessing murky. Very little is known about the but was not seriously contemplated by mathematicians. -

Logic Puzzles Supplies

STEM Skill Booster: Logic Puzzles Supplies Puzzle Packet Pencil/Pen (not included) Scissors (not included) Instructions Can you solve the sphinx’s logic puzzles? Design an unsolvable maze? Answer brain-twisting riddles? Follow along to build your logic and puzzle solving skills to beat the sphinx. Flip the page to pass through mazes, solve riddles and even create your own puzzles along the way. STEM Concepts Problem Solving – process of finding solutions to difficult tasks, puzzles or concepts Maze – a setup of paths designed as a puzzle through which one has to find a way out or to the finish Tangram –a dissection puzzle of flat shapes which are put together to form shapes Riddle – challenge to think outside the box and beyond the obvious answer to explain a situation or solution Deductive Reasoning – using what you know is true or what you know is not tur to figure out other facts or answers. Mazes A maze is a complex, branching puzzle through which the solver must find a route. See if you can find a path through these mazes. Design Your Own Maze Use the space below to create your own maze. Make sure to create one clear path for someone to follow, with a start and finish. Then add in other paths that mislead or come to a dead end. Next, have your family try it out. Are they able to solve it? l Build It: Labyrinth Do you know the difference between a maze and a labyrinth? A maze is a complex branching puzzle through which the solver must find a route. -

Monte-Carlo Tree Search Using Expert Knowledge: an Application to Computer Go and Human Genetics

Curso 2012/13 CIENCIAS Y TECNOLOGÍAS/23 I.S.B.N.: 978-84-15910-90-9 SANTIAGO BASALDÚA LEMARCHAND Monte-Carlo tree search using expert knowledge: an application to computer go and human genetics Directores J. MARCOS MORENO VEGA CARLOS A. FLORES INFANTE SOPORTES AUDIOVISUALES E INFORMÁTICOS Serie Tesis Doctorales ciencias 23 (Santiago Basaldúa Lemarchand).indd 1 18/02/2014 11:24:43 Universidad de La Laguna Abstract Monte-Carlo Tree Search Using Expert Knowledge: An Application to Computer Go and Human Genetics During the years in which the research described in this PhD dissertation was done, Monte-Carlo Tree Search has become the preeminent algorithm in many AI and computer science fields. This dissertation analyzes how expert knowledge and also online learned knowledge can be used to enhance the search. The work describes two different implementations: as a two player search in computer go and as an optimization method in human genetics. It is established that in large problems MCTS has to be combined with domain specific or online learned knowledge to improve its strength. This work analyzes different successful ideas about how to do it, the resulting findings and their implications, hence improving our insight of MCTS. The main contributions to the field are: an analytical mathematical model improving the understanding of simulations, a problem definition and a framework including code and data to compare algorithms in human genetics and three successful implementations: in the field of 19x19 go openings named M-eval, in the field of learning playouts and in the field of genetic etiology. Also, an open source integer representation of proportions as Win/Loss States (WLS), a negative result in the field of playouts, an unexpected finding of a possible problem in optimization and further insight on the limitations of MCTS are worth mentioning. -

Math 25A Homework 7

Math 25a Homework 7 Due Tuesday 8th November 2005. Half of this problem set will be graded by Alison and half by Ivan. Please turn in problems from Section 1 separately from the problems in Section 2. Remember to staple each bundle of solutions and also to put your name on each! As we all have to suffer through a midterm exam next week, I’ve tried to make this week’s HW a) shorter and b) easier than usual. Warning —- the next set will be more challenging! 1 Alison’s problems (1) Problem 5 on page 19 of Axler. (2) Problem 6 on page 19 of Axler. (3) Problem 9 on page 19 of Axler. 2 Ivan’s problems (1) Problem 13 on page 19 of Axler. (2) Problem 15 on page 19 of Axler. (3) Problem 1 on page 35 of Axler. (4) Problem 2 on page 35 of Axler. 3 Warm up and Extra Problems. There are HEAPS of great linear algebra problems. Problems 3 and 4 on page 19 of Axler get you to think about some more consequences of the vector space axioms. Problems 7, 8 and 10 on page 19 of Axler get you thinking about subspaces. Question 14 is a nice example to help get you used to thinking about the vector space of polynomial functions. 1 4 The Math Puzzler - just for fun! Each week there will be a “math puzzler” for the class to think about. Please feel free to submit a “puzzler” you think the class might enjoy. The “puzzlers” don’t have to be difficult, nor related to the material in class — they just have to be fun to think about! More from the Island of Dreamers. -

Area Maze Madness : Stretch Your Brain with Fun Math and Challenging Logic Puzzles Pdf, Epub, Ebook

AREA MAZE MADNESS : STRETCH YOUR BRAIN WITH FUN MATH AND CHALLENGING LOGIC PUZZLES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Graham Jones | 128 pages | 19 Nov 2019 | Ulysses Press | 9781612439426 | English | none Area Maze Madness : Stretch Your Brain with Fun Math and Challenging Logic Puzzles PDF Book Following written and even oral directions can be a difficult task for many students. But this is a word search with a twist. Controls are easy and the puzzles are fun. By Jon Flippin. Nov 6, One complaint, though. Already have an account? Crosswords Links to daily crossword puzzles and resources. By Jason Hamilton. So I have to just guess? Hundred is a square grid, whose cells are to be filled by some digits. I think it would be cool if some of the answers had another layer of hand holding to help guide me through solutions a little more, and how I can think differently through areas where I probably got stuck. By Colleen McCallum. Puzzles are known to boost brain power—they improve memory, spatial awareness, logic, and problem-solving. The Monty Hall Problem: Beyond…. Lawyers defend man who stole lectern during capital riots TZ. Suguru Sometimes called Tectonics or Number Blocks , these puzzles have very simple rules but can be extremely challenging. I would have liked some harder levels the further you went along. Just using the grid doesn't help as much with the relationships that the clues give. The collection has grid-based logic puzzles for you to try your hand at, ranging from easy to exceptionally challenging. One solution can be found here. -

Secrets of the MIT Mystery Hunt: an Exploration of the Theory Underlying the Construction of a Multi-Puzzle Contest

Secrets of the MIT Mystery Hunt: An Exploration of the Theory Underlying the Construction of a Multi-Puzzle Contest by Mark Louis Gottlieb Submitted to the Program in Writing and Humanistic Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science in Humanities and Engineering at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY May 1998 @Mark Louis Gottlieb, MCMXCVIII. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Author...-- -------------...................... ............... ....... Program in Writing and Humanistic Studies May 8, 1998 C ertified by .............................................................. ................................. Edward Barrett Senior Lecturer Thesis Supervisor Accepted by ......... ........................ ....................... James Paradis Head, Program in Writing and Humanistic Studies MASSACHUETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUL 881 4oIr=WLIBRA~in Secrets of the MIT Mystery Hunt: An Exploration of the Theory Underlying the Construction of a Multi-Puzzle Contest by Mark Louis Gottlieb Submitted to the Program in Writing and Humanistic Studies on May 8, 1998 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science in Humanities and Engineering Abstract This is an exploration of the rules and guidelines that underlie the structure of a multi-puzzle contest (a competition consisting of one large puzzle made up of a number of smaller -

045 – Puzzle Genres — Fonts Puzzle

045 – Puzzle Genres — Fonts puzzle — Word puzzles Word games/puzzles are spoken, paper-&-pencil or board games often designed to test ability with language or to explore its properties. ● Scrabble There are a number of different types of this game, with every game having the same end goal : try to spell or form a word using the letters that you are given. Each player will be given set letters and will have to use them to create words, generally on a grid, and usually intersecting with other letters and words that have already been played. It is a great way to test not only spelling, but also vocabulary skills and even thinking skills. As players place more and more letters on the board, these games tend to become much more difficult, as there are fewer spaces that are left for players to play their letters. ● Word Search For adults or children, these puzzles require players to try to find specific words in a jumble of other letters. The letters are usually laid out in a traditional grid, with letters neatly in rows and columns, which allows players to quickly and easily find the words they are looking for. Generally speaking, players can look horizontally, vertically, and diagonally when searching for words. Words can be written forwards and backwards, which can make these puzzles difficult. There are some types of word search puzzles where the user is able to make turns when circling a word, which means that they don’t have to try to stay in a straight line. Puzzle Genres — Fonts puzzle ● Page 1 of 7 ● Crossword These are word puzzles where the user must fill in empty squares with the letters of a word that fits the listed clue.