Chapter-1.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strike and Dip Refer to the Orientation Or Attitude of a Geologic Feature. The

Name__________________________________ 89.325 – Geology for Engineers Faults, Folds, Outcrop Patterns and Geologic Maps I. Properties of Earth Materials When rocks are subjected to differential stress the resulting build-up in strain can cause deformation. Depending on the material properties the result can either be elastic deformation which can ultimately lead to the breaking of the rock material (faults) or ductile deformation which can lead to the development of folds. In this exercise we will look at the various types of deformation and how geologists use geologic maps to understand this deformation. II. Strike and Dip Strike and dip refer to the orientation or attitude of a geologic feature. The strike line of a bed, fault, or other planar feature, is a line representing the intersection of that feature with a horizontal plane. On a geologic map, this is represented with a short straight line segment oriented parallel to the strike line. Strike (or strike angle) can be given as either a quadrant compass bearing of the strike line (N25°E for example) or in terms of east or west of true north or south, a single three digit number representing the azimuth, where the lower number is usually given (where the example of N25°E would simply be 025), or the azimuth number followed by the degree sign (example of N25°E would be 025°). The dip gives the steepest angle of descent of a tilted bed or feature relative to a horizontal plane, and is given by the number (0°-90°) as well as a letter (N, S, E, W) with rough direction in which the bed is dipping. -

Field Geology

FIELD GEOLOGY GUIDEBOOK AND NOTES ILLINOIS STATE UNIVERSITY 2018 Version 2 Table of Contents Syllabus 5 Schedule 8 Hazard Recognition Mitigation 9 Geologic Field Notes 17 Reconnaissance Notes 17 Measuring Stratigraphic Column Notes 18 Geologic Mapping Notes 19 Geologic Maps and Mapping 22 Variables affecting the appearance of a geologic map 23 Techniques to test the quality and accuracy of your map 23 Common map errors 24 Official USGS map colors 24 Rule of V’s 25 Geologic Cross Sections 26 Basic principles of cross section construction 26 Apparent dips: correct use of strike and dip data in cross sections 27 Common cross section errors 27 Steps in making a topographic profile for a geologic cross section 28 Constructing geologic cross sections using down-plunge projection 29 Phanerozoic Stratigraphy of North America 33 Tectonic History of the U.S. Cordillera 38 Regional Cross-sections through Wyoming 41 Wyoming Stratigraphic Nomenclature Chart 42 Rock Sequence in the Bighorn Basin 43 Rock Sequence in the Powder River Basin 44 Black Hills Precambrian Geology 45 Project Descriptions 47 Regional Stratigraphy 47 Amsden Creek Big Game Winter Range 49 Steerhead Ranch 50 Alkali 53 South Fork 55 Mickelson 57 Moonshine 60 Appendix 1: Essential Analysis Tools and Techniques for Field Geology 62 Field description of rocks 62 Measuring stratigraphic sections 69 Calculating layer thicknesses 76 Alignment diagram for calculating apparent dip 77 Calculating strike and dip of a surface from contacts on a map 78 Calculating outcrop patterns from field -

FIELD TRIP: Contractional Linkage Zones and Curved Faults, Garden of the Gods, with Illite Geochronology Exposé

FIELD TRIP: Contractional linkage zones and curved faults, Garden of the Gods, with illite geochronology exposé Presenters: Christine Siddoway and Elisa Fitz Díaz. With contributions from Steven A.F. Smith, R.E. Holdsworth, and Hannah Karlsson This trip examines the structural geology and fault geochronology of Garden of the Gods, Colorado. An enclave of ‘red rock’ terrain that is noted for the sculptural forms upon steeply dipping sandstones (against the backdrop of Pikes Peak), this site of structural complexity lies at the south end of the Rampart Range fault (RRF) in the southern Colorado Front Range. It features Laramide backthrusts, bedding plane faults, and curved fault linkages within subvertical Mesozoic strata in the footwall of the RRF. Special subjects deserving of attention on this SGTF field trip are deformation band arrays and younger-upon-older, top-to-the-west reverse faults—that well may defy all comprehension! The timing of RRF deformation and formation of the Colorado Front Range have long been understood only in general terms, with reference to biostratigraphic controls within Laramide orogenic sedimentary rocks, that derive from the Laramide Front Range. Using 40Ar/39Ar illite age analysis of shear-generated illite, we are working to determine the precise timing of fault movement in the Garden of the Gods and surrounding region provide evidence for the time of formation of the Front Range monocline, to be compared against stratigraphic-biostratigraphic records from the Denver Basin. The field trip will complement an illite geochronology workshop being presented by Elisa Fitz Díaz on 19 June. If time allows, and there is participant interest, we will make a final stop to examine fault-bounded, massive sandstone- and granite-hosted clastic dikes that are associated with the Ute Pass fault. -

Faults and Joints

133 JOINTS Joints (also termed extensional fractures) are planes of separation on which no or undetectable shear displacement has taken place. The two walls of the resulting tiny opening typically remain in tight (matching) contact. Joints may result from regional tectonics (i.e. the compressive stresses in front of a mountain belt), folding (due to curvature of bedding), faulting, or internal stress release during uplift or cooling. They often form under high fluid pressure (i.e. low effective stress), perpendicular to the smallest principal stress. The aperture of a joint is the space between its two walls measured perpendicularly to the mean plane. Apertures can be open (resulting in permeability enhancement) or occluded by mineral cement (resulting in permeability reduction). A joint with a large aperture (> few mm) is a fissure. The mechanical layer thickness of the deforming rock controls joint growth. If present in sufficient number, open joints may provide adequate porosity and permeability such that an otherwise impermeable rock may become a productive fractured reservoir. In quarrying, the largest block size depends on joint frequency; abundant fractures are desirable for quarrying crushed rock and gravel. Joint sets and systems Joints are ubiquitous features of rock exposures and often form families of straight to curviplanar fractures typically perpendicular to the layer boundaries in sedimentary rocks. A set is a group of joints with similar orientation and morphology. Several sets usually occur at the same place with no apparent interaction, giving exposures a blocky or fragmented appearance. Two or more sets of joints present together in an exposure compose a joint system. -

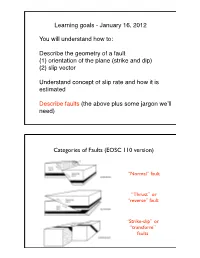

Describe the Geometry of a Fault (1) Orientation of the Plane (Strike and Dip) (2) Slip Vector

Learning goals - January 16, 2012 You will understand how to: Describe the geometry of a fault (1) orientation of the plane (strike and dip) (2) slip vector Understand concept of slip rate and how it is estimated Describe faults (the above plus some jargon weʼll need) Categories of Faults (EOSC 110 version) “Normal” fault “Thrust” or “reverse” fault “Strike-slip” or “transform” faults Two kinds of strike-slip faults Right-lateral Left-lateral (dextral) (sinistral) Stand with your feet on either side of the fault. Which side comes toward you when the fault slips? Another way to tell: stand on one side of the fault looking toward it. Which way does the block on the other side move? Right-lateral Left-lateral (dextral) (sinistral) 1992 M 7.4 Landers, California Earthquake rupture (SCEC) Describing the fault geometry: fault plane orientation How do you usually describe a plane (with lines)? In geology, we choose these two lines to be: • strike • dip strike dip • strike is the azimuth of the line where the fault plane intersects the horizontal plane. Measured clockwise from N. • dip is the angle with respect to the horizontal of the line of steepest descent (perpendic. to strike) (a ball would roll down it). strike “60°” dip “30° (to the SE)” Profile view, as often shown on block diagrams strike 30° “hanging wall” “footwall” 0° N Map view Profile view 90° W E 270° S 180° Strike? Dip? 45° 45° Map view Profile view Strike? Dip? 0° 135° Indicating direction of slip quantitatively: the slip vector footwall • let’s define the slip direction (vector) -

FM 5-410 Chapter 2

FM 5-410 CHAPTER 2 Structural Geology Structural geology describes the form, pat- secondary structural features. These secon- tern, origin, and internal structure of rock dary features include folds, faults, joints, and and soil masses. Tectonics, a closely related schistosity. These features can be identified field, deals with structural features on a and m appeal in the field through site inves- larger regional, continental, or global scale. tigation and from remote imagery. Figure 2-1, page 2-2, shows the major plates of the earth’s crust. These plates continually Section I. Structural Features undergo movement as shown by the arrows. in Sedimentary Rocks Figure 2-2, page 2-3, is a more detailed repre- sentation of plate tectonic theory. Molten material rises to the earth’s surface at BEDDING PLANES midoceanic ridges, forcing the oceanic plates Structural features are most readily recog- to diverge. These plates, in turn, collide with nized in the sedimentary rocks. They are adjacent plates, which may or may not be of normally deposited in more or less regular similar density. If the two colliding plates are horizontal layers that accumulate on top of of approximately equal density, the plates each other in an orderly sequence. Individual will crumple, forming mountain range along deposits within the sequence are separated the convergent zone. If, on the other hand, by planar contact surfaces called bedding one of the plates is more dense than the other, planes (see Figure 1-7, page 1-9). Bedding it will be subducted, or forced below, the planes are of great importance to military en- lighter plate, creating an oceanic trench along gineers. -

Mercian 11 B Hunter.Indd

The Cressbrook Dale Lava and Litton Tuff, between Longstone and Hucklow Edges, Derbyshire John Hunter and Richard Shaw Abstract: With only a small exposure near the head of its eponymous dale, the Cressbrook Dale Lava is the least exposed of the major lava flows interbedded within the Carboniferous platform- carbonate succession of the Derbyshire Peak District. It underlies a large area of the limestone plateau between Longstone Edge and the Eyam and Hucklow edges. The recent closure of all of the quarries and underground mines in this area provided a stimulus to locate and compile the existing subsurface information relating to the lava-field and, supplemented by airborne geophysical survey results, to use these data to interpret the buried volcanic landscape. The same sub-surface data-set is used to interpret the spatial distribution of the overlying Litton Tuff. Within the regional north-south crustal extension that survey indicate that the outcrops of igneous rocks in affected central and northern Britain on the north side the White Peak are only part of a much larger volcanic of the Wales-Brabant High during the early part of the field, most of which is concealed at depth beneath Carboniferous, a province of subsiding platforms, tilt- Millstone Grit and Coal Measures farther east. Because blocks and half-grabens developed beneath a shallow no large volcano structures have been discovered so continental sea. Intra-plate magmatism accompanied far, geological literature describes the lavas in the the lithospheric thinning, with basic igneous rocks White Peak as probably originating from four separate erupting at different times from a number of small, local centres, each being active in a different area at different volcanic centres scattered across a region extending times (Smith et al., 2005). -

Ductile Deformation - Concepts of Finite Strain

327 Ductile deformation - Concepts of finite strain Deformation includes any process that results in a change in shape, size or location of a body. A solid body subjected to external forces tends to move or change its displacement. These displacements can involve four distinct component patterns: - 1) A body is forced to change its position; it undergoes translation. - 2) A body is forced to change its orientation; it undergoes rotation. - 3) A body is forced to change size; it undergoes dilation. - 4) A body is forced to change shape; it undergoes distortion. These movement components are often described in terms of slip or flow. The distinction is scale- dependent, slip describing movement on a discrete plane, whereas flow is a penetrative movement that involves the whole of the rock. The four basic movements may be combined. - During rigid body deformation, rocks are translated and/or rotated but the original size and shape are preserved. - If instead of moving, the body absorbs some or all the forces, it becomes stressed. The forces then cause particle displacement within the body so that the body changes its shape and/or size; it becomes deformed. Deformation describes the complete transformation from the initial to the final geometry and location of a body. Deformation produces discontinuities in brittle rocks. In ductile rocks, deformation is macroscopically continuous, distributed within the mass of the rock. Instead, brittle deformation essentially involves relative movements between undeformed (but displaced) blocks. Finite strain jpb, 2019 328 Strain describes the non-rigid body deformation, i.e. the amount of movement caused by stresses between parts of a body. -

Semester -3 Civil Engineering

CIVIL ENGINEERING SEMESTER -3 CIVIL ENGINEERING Year of MECHANICS OF CATEGORY L T P CREDIT CET201 Introduction SOLIDS PCC 3 1 0 4 2019 Preamble: Mechanics of solids is one of the foundation courses in the study of structural systems. The course provides the fundamental concepts of mechanics of deformable bodies and helps students to develop their analytical and problem solving skills. The course introduces students to the various internal effects induced in structural members as well as their deformations due to different types of loading. After this course students will be able to determine the stress, strain and deformation of loaded structural elements. Prerequisite: EST 100 Engineering Mechanics Course Outcomes: After the completion of the course the student will be able to Prescribed Course Description of Course Outcome Outcome learning level Recall the fundamental terms and theorems associated with CO1 Remembering mechanics of linear elastic deformable bodies. Explain the behavior and response of various structural CO2 Understanding elements under various loading conditions. Apply the principles of solid mechanics to calculate internal stresses/strains, stress resultants and strain energies in CO3 Applying structural elements subjected to axial/transverse loadsand bending/twisting moments. Choose appropriate principles or formula to find the elastic CO4 constants of materials making use of the information Applying available. Perform stress transformations, identify principal planes/ CO5 stresses and maximum shear stress at a point -

Collision Orogeny

Downloaded from http://sp.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on October 6, 2021 PROCESSES OF COLLISION OROGENY Downloaded from http://sp.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on October 6, 2021 Downloaded from http://sp.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on October 6, 2021 Shortening of continental lithosphere: the neotectonics of Eastern Anatolia a young collision zone J.F. Dewey, M.R. Hempton, W.S.F. Kidd, F. Saroglu & A.M.C. ~eng6r SUMMARY: We use the tectonics of Eastern Anatolia to exemplify many of the different aspects of collision tectonics, namely the formation of plateaux, thrust belts, foreland flexures, widespread foreland/hinterland deformation zones and orogenic collapse/distension zones. Eastern Anatolia is a 2 km high plateau bounded to the S by the southward-verging Bitlis Thrust Zone and to the N by the Pontide/Minor Caucasus Zone. It has developed as the surface expression of a zone of progressively thickening crust beginning about 12 Ma in the medial Miocene and has resulted from the squeezing and shortening of Eastern Anatolia between the Arabian and European Plates following the Serravallian demise of the last oceanic or quasi- oceanic tract between Arabia and Eurasia. Thickening of the crust to about 52 km has been accompanied by major strike-slip faulting on the rightqateral N Anatolian Transform Fault (NATF) and the left-lateral E Anatolian Transform Fault (EATF) which approximately bound an Anatolian Wedge that is being driven westwards to override the oceanic lithosphere of the Mediterranean along subduction zones from Cephalonia to Crete, and Rhodes to Cyprus. This neotectonic regime began about 12 Ma in Late Serravallian times with uplift from wide- spread littoral/neritic marine conditions to open seasonal wooded savanna with coiluvial, fluvial and limnic environments, and the deposition of the thick Tortonian Kythrean Flysch in the Eastern Mediterranean. -

Characterization of Olivine Fabrics and Mylonite in the Presence of Fluid

Jung et al. Earth, Planets and Space 2014, 66:46 http://www.earth-planets-space.com/content/66/1/46 FULL PAPER Open Access Characterization of olivine fabrics and mylonite in the presence of fluid and implications for seismic anisotropy and shear localization Sejin Jung1, Haemyeong Jung1* and Håkon Austrheim2 Abstract The Lindås Nappe, Bergen Arc, is located in western Norway and displays two high-grade metamorphic structures. A Precambrian granulite facies foliation is transected by Caledonian fluid-induced eclogite-facies shear zones and pseudotachylytes. To understand how a superimposed tectonic event may influence olivine fabric and change seismic anisotropy, two lenses of spinel lherzolite were studied by scanning electron microscope (SEM) and electron back-scattered diffraction (EBSD) techniques. The granulite foliation of the surrounding anorthosite complex is displayed in ultramafic lenses as a modal variation in olivine, pyroxenes, and spinel, and the Caledonian eclogite-facies structure in the surrounding anorthosite gabbro is represented by thin (<1 cm) garnet-bearing ultramylonite zones. The olivine fabrics in the spinel bearing assemblage were E-type and B-type and a combination of A- and B-type lattice preferred orientations (LPOs). There was a change in olivine fabric from a combination of A- and B-type LPOs in the spinel bearing assemblage to B- and E-type LPOs in the garnet lherzolite mylonite zones. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy analyses reveal that the water content of olivine in mylonite is much higher (approximately 600 ppm H/Si) than that in spinel lherzolite (approximately 350 ppm H/Si), indicating that water caused the difference in olivine fabric. -

The Mylonite Issue 16 November 2008

INSIDE • News from the Chair • Special Announcements • Faculty • Alumni The Newsletter of the Geological Sciences Dept. Calif. State Polytechnic University Pomona, Calif. The Mylonite Issue 16 November 2008 NEWS FROM THE CHAIR NOTE FROM THE CHAIR 2008 Spending was severely curtailed. The Mylonite Once again, greetings to each and every one of was one of those “non-essential” items. It was only you! This will be the last letter I write to you all as Chair through collective Department persistence, the immense of the Geological Sciences Department. It is time for a help of Ms. Mary Jo Gruca, the College’s Development change in leadership, new ideas and new approaches. I Director, and the University’s Office of Advancement will end my tenure as Chair at the commencement of the were we able to send the Mylonite out to all of you. It spring quarter of 2009. At that time, Dr. Jon Nourse will was no easy task. take over the responsibilities. It has been a true pleasure All faculty searches within the College of and a privilege to have served you all for so long. Science were cancelled. Geology had already begun Reflecting back on this past year, there is no doubt it was advertising and was receiving applications when our my most difficult year as Chair. The report below is far search for a Sedimentary Geologist was ended. As of from up beat and only peripherally related to my this writing, the Sedimentary Geology position remains stepping down as chair. vacant and there is no faculty search underway.