Kodo One Earth Tour: Evolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5Th Competition Award Ceremony Program 2010

The Japan Center at Stony Brook (JCSB) Annual Meeting JCSB-Canon Essay Competition Award Ceremony 10:00 – 11:15 a.m. (Chapel) 12:15 -1 p.m. (Chapel) Opening Remarks: Opening Remarks: Iwao Ojima, JCSB President Iwao Ojima, JCSB President & Chair of the Board Greetings: Mark Aronoff, Vice Provost, Stony Brook University Financial Report: Joseph G. Warren, Vice President & General Manager, Canon U.S.A.; Chairman & COO, Patricia Marinaccio, JCSB Treasurer & Executive Committee Canon Information Technology Services, Inc. Result of the Essay Competition: Eriko Sato, Organizing Committee Chair Public Relations: JCSB Award for Promoting the Awareness of Japan: Roxanne Brockner, JCSB Executive Committee Presenter: Iwao Ojima Patrick J. Cauchi (English teacher at Longwood Senior High School) The Outreach Program: Best Essay Awards: Gerry Senese, Principal of Ryu Shu Kan dojo, JCSB Outreach Program Director Moderator: Sachiko Murata, Chief Judge Presenters: Mark Aronoff, Joseph Warren, and Iwao Ojima High School Division Best Essay Award The Long Island Japanese Association: st Eriko Sato, Long Island Japanese Association (LIJA), JCSB Board Member 1 Place ($2,000 cash and a Canon camera) A World Apart by Gen Ishikawa (Syosset High School) nd 2 Place ($1,000 cash and a Canon camera) Journey to a Japanese Family by Ethan Hamilton (Horace Mann High School) Pre-College Japanese Language Program: rd Eriko Sato, Director of Pre-College Japanese Language Program, JCSB Board Member 3 Place ($500 cash and a Canon camera) What Japan Means to Me by Sarah Lam (Bronx High School of Science) Honorable Mention ($100 cash) Program in Japanese Studies: Life of Gaman by Sandy Patricia Guerrero (Longwood Senior High School) (a) Current Status of the Program in Japanese Studies at Stony Brook University: Origami by Stephanie Song (Fiorello H. -

Dayton C. Miller Flute Collection

Guides to Special Collections in the Music Division at the Library of Congress Dayton C. Miller Flute Collection LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON 2004 Table of Contents Introduction...........................................................................................................................................................iii Biographical Sketch...............................................................................................................................................vi Scope and Content Note......................................................................................................................................viii Description of Series..............................................................................................................................................xi Container List..........................................................................................................................................................1 FLUTES OF DAYTON C. MILLER................................................................................................................1 ii Introduction Thomas Jefferson's library is the foundation of the collections of the Library of Congress. Congress purchased it to replace the books that had been destroyed in 1814, when the Capitol was burned during the War of 1812. Reflecting Jefferson's universal interests and knowledge, the acquisition established the broad scope of the Library's future collections, which, over the years, were enriched by copyright -

University of Nevada, Reno American Shinto Community of Practice

University of Nevada, Reno American Shinto Community of Practice: Community formation outside original context A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology By Craig E. Rodrigue Jr. Dr. Erin E. Stiles/Thesis Advisor May, 2017 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by CRAIG E. RODRIGUE JR. Entitled American Shinto Community Of Practice: Community Formation Outside Original Context be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Erin E. Stiles, Advisor Jenanne K. Ferguson, Committee Member Meredith Oda, Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School May, 2017 i Abstract Shinto is a native Japanese religion with a history that goes back thousands of years. Because of its close ties to Japanese culture, and Shinto’s strong emphasis on place in its practice, it does not seem to be the kind of religion that would migrate to other areas of the world and convert new practitioners. However, not only are there examples of Shinto being practiced outside of Japan, the people doing the practice are not always of Japanese heritage. The Tsubaki Grand Shrine of America is one of the only fully functional Shinto shrines in the United States and is run by the first non-Japanese Shinto priest. This thesis looks at the community of practice that surrounds this American shrine and examines how membership is negotiated through action. There are three main practices that form the larger community: language use, rituals, and Aikido. Through participation in these activities members engage with an American Shinto community of practice. -

Teachers' Notes:Taiko Drums & Flutes of Japan Japanese Musical

Teachers’ Notes: Taiko Drums & Flutes of Japan Japanese Musical Instruments Shakuhachi This Japanese flute with only five finger holes is made of the root end of a heavy variety of bamboo. From around 1600 through to the late 1800’s the shakuhachi was used exclusively as a tool for Zen meditation. Since the Meiji restoration (1868), the shakuhachi has performed in chamber music combinations with koto (zither), shamisen (lute) and voice. In the 20 th century, shakuhachi has performed in many types of ensembles in combination with non-Japanese instruments. It’s characteristic haunting sounds, evocative of nature, are frequently featured in film music. Koto (in Anne’s Japanese Music Show, not Taiko performance) Like the shakuhachi , the koto (a 13 stringed zither) ORIGINATED IN China and a uniquely Japanese musical vocabulary and performance aesthetic has gradually developed over its 1200 years in Japan. Used both in ensemble and as a solo virtuosic instrument, this harp-like instrument has a great tuning flexibility and has therefore adapted well to cross cultural music genres. Taiko These drums come in many sizes and have been traditionally associated with religious rites at Shinto shrines as well as village festivals. In the last 30 years, Taiko drumming groups have flourished in Japan and have become poplar worldwide for their fast pounding rhythms. Sasara A string of small wooden slats, which make a large rattling sound when played with a “whipping” action. Kane A small hand held gong. Chappa A small pair of cymbals Sasara Kane Bookings -

An Analysis of Twentieth-Century Flute Sonatas by Ikuma Dan, Hikaru

Flute Repertoire from Japan: An Analysis of Twentieth-Century Flute Sonatas by Ikuma Dan, Hikaru Hayashi, and Akira Tamba D.M.A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Daniel Ryan Gallagher, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2019 D.M.A. Document Committee: Professor Katherine Borst Jones, Advisor Dr. Arved Ashby Dr. Caroline Hartig Professor Karen Pierson 1 Copyrighted by Daniel Ryan Gallagher 2019 2 Abstract Despite the significant number of compositions by influential Japanese composers, Japanese flute repertoire remains largely unknown outside of Japan. Apart from standard unaccompanied works by Tōru Takemitsu and Kazuo Fukushima, other Japanese flute compositions have yet to establish a permanent place in the standard flute repertoire. The purpose of this document is to broaden awareness of Japanese flute compositions through the discussion, analysis, and evaluation of substantial flute sonatas by three important Japanese composers: Ikuma Dan (1924-2001), Hikaru Hayashi (1931- 2012), and Akira Tamba (b. 1932). A brief history of traditional Japanese flute music, a summary of Western influences in Japan’s musical development, and an overview of major Japanese flute compositions are included to provide historical and musical context for the composers and works in this document. Discussions on each composer’s background, flute works, and compositional style inform the following flute sonata analyses, which reveal the unique musical language and characteristics that qualify each work for inclusion in the standard flute repertoire. These analyses intend to increase awareness and performance of other Japanese flute compositions specifically and lesser- known repertoire generally. -

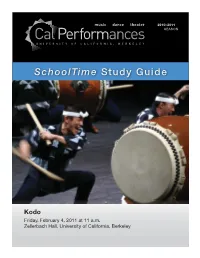

Kodo Study Guide 1011.Indd

2010–2011 SEASON SchoolTime Study Guide Kodo Friday, February 4, 2011 at 11 a.m. Zellerbach Hall, University of California, Berkeley Welcome to SchoolTime On Friday, February 4 at 11am, your class will att end a SchoolTime performance of Kodo (Taiko drumming) at Cal Performances’ Zellerbach Hall. In Japan, “Kodo” meana either “hearbeat” or “children of the drum.” These versati le performers play a variety of instruments – some massive in size, some extraordinarily delicate that mesmerize audiences. Performing in unison, they wield their sti cks like expert swordsmen, evoking thrilling images of ancient and modern Japan. Witnessing a performance by Kodo inspires primal feelings, like plugging into the pulse of the universe itself. Using This Study Guide You can use this study guide to engage your students and enrich their Cal Performances fi eld trip. Before att ending the performance, we encourage you to: • Copy the Student Resource Sheet on pages 2 & 3 for your students to use before the show. • Discuss the informati on on pages 4-5 About the Performance & Arti sts. • Read About the Art Form on page 6, and About Japan on page 11 with your students. • Engage your class in two or more acti viti es on pages 13-14. • Refl ect by asking students the guiding questi ons, found on pages 2,4,6 & 11. • Immerse students further into the subject matt er and art form by using the Resource and Glossary secti ons on pages 15 & 16. At the performance: Your class can acti vely parti cipate during the performance by: • Listening to Kodo’s powerful drum rhythms and expressive music • Observing how the performers’ movements and gestures enhance the performance • Thinking about how you are experiencing a bit of Japanese culture and history by att ending a live performance of taiko drumming • Marveling at the skill of the performers • Refl ecti ng on the sounds, sights, and performance skills you experience at the theater. -

Thank You, and Congratulations on Your Choice of the SRX-09

SRX-09_je 1 ページ 2007年3月17日 土曜日 午後2時48分 201a Before using this unit, carefully read the sections entitled: “USING THE UNIT SAFELY” and “IMPORTANT NOTES” (p. 2; p. 4). These sections provide important information concerning the proper operation of the unit. Additionally, in order to feel assured that you have gained a good grasp of every feature provided by your new unit, Owner’s manual should be read in its entirety. The manual should be saved and kept on hand as a convenient reference. 201a この機器を正しくお使いいただくために、ご使用前に「安全上のご注意」(P.3)と「使用上のご注意」(P.4)をよく お読みください。また、この機器の優れた機能を十分ご理解いただくためにも、この取扱説明書をよくお読みくださ い。取扱説明書は必要なときにすぐに見ることができるよう、手元に置いてください。 Thank you, and congratulations on your choice of the SRX-09 このたびは、ウェーブ・エクスパンション・ボード SRX-09 “SR-JV80 Collection Vol.4 World Collection” Wave 「SR-JV80 Collection Vol.4 World Collection」をお買い上 Expansion Board. げいただき、まことにありがとうございます。 This expansion board contains all of the waveforms in the このエクスパンション・ボードは SR-JV80-05 World、14 World SR-JV80-05 World, SR-JV80-14 World Collection “Asia,” and Collection "Asia"、18 World Collection "LATIN" に搭載されていた SR-JV80-18 World Collection “LATIN,” along with specially ウェーブフォームを完全収録、17 Country Collection に搭載されて selected titles from waveforms contained in the 17 Country いたウェーブフォームから一部タイトルを厳選して収録しています。 Collection. This board contains new Patches and Rhythm これらのウェーブフォームを組み合わせた SRX 仕様の Sets which combine the waveforms in a manner that Effect、Matrix Control を生かした新規 パッチ、リズム・ highlights the benefits of SRX Effects and Matrix Control. セットを搭載しています。 This board contains all kinds of unique string, wind, and アフリカ、アジア、中近東、南米、北米、オーストラリア、 percussion instrument sounds, used in ethnic music from ヨーロッパ等、世界中のユニークで様々な弦楽器、管楽器、 Africa, Asia, the Middle East, South and North America, 打楽器などの各種民族楽器の音色を収録しています。 Australia, and Europe. -

Perspectives in North American Taiko Sano and Uyechi, Spring 2004

Music 17Q Perspectives in North American Taiko Sano and Uyechi, Spring 2004 M W: 2:15 – 4:05 p.m., Braun 106 (M), Braun Rehearsal Hall (W) 4 units Course Syllabus Taiko, used here to refer to performance ensemble drumming using the taiko, or Japanese drum, is a relative newcomer to the American music scene. The emergence of the first North American groups coincided with increased activism in the Japanese American community and, to some, is symbolic of Japanese American identity. To others, North American taiko is associated with Japanese American Buddhism, and to others taiko is a performance art rooted in Japan. In this course we will explore the musical, cultural, historical, and political perspectives of taiko in North America through drumming (hands-on experience), readings, class discussions, workshops, and a research project. With taiko as the focal point, we will learn about Japanese music and Japanese American history, and explore relations between performance, cultural expression, community, and identity. COURSE REQUIREMENTS Students must attend all workshops and complete all assignments to receive credit for the course. Reaction Papers (30%) Midterm (20%) Research Project (40%) Attendance/Participation (10%) COURSE FEE $30 to partially cover cost of bachi, bachi bag, concert tickets, workshop fees, gas and parking for drivers. READINGS 1. Course reader available at the Stanford Bookstore. 2. Strangers From a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans. Ronald Takaki. 1989. Penguin Books. GENERAL INFORMATION Instructors Steve Sano Linda Uyechi Office Braun 120 Office Phone 723-1570 Phone 494-1321 494-1321 (8 a.m. – 10 p.m.) Email sano@leland [email protected] 1 COURSE OUTLINE WEEK 1 (March 31) Wednesday Introduction: What is North American Taiko? Reading Terada, Y. -

Chapter 5: Music

CHAPTER 5 MUSIC Revised October 2010 5.1. TITLE AND STATEMENT OF RESPONSIBILITY AREA 5.1B. Title proper 5.1B1. Transcribe the title proper as instructed in 1.1B. If a title consists of the name(s) of one or more type(s) of composition, or one or more type(s) of composition and one or more of the following: medium of performance key date of composition number treat type of composition, medium of performance, etc., as the title proper. In all other cases, if one or more statements of medium of performance, key, date of composition, and/or number are found in the source of information, treat those elements as other title information (see 5.1E). In case of doubt, treat statements of medium of performance, key, date of composition, and number as part of the title proper. If the title proper is not taken from the chief source of information, give the source of the title in a note (see 5.7B3). 245 10 $a “Dou E yuan” ge ju xuan qu 245 10 $a Gasshō no tame no konpojishon. $n II 245 10 $a 合唱のためのコンポジション. $n II 245 10 $a Gagaku uchimono sōfu 245 10 $a 雅楽打物奏譜 245 10 $a Yongun no tame no keishō 245 10 $a 四群のための形象 245 10 $a Yŏn’gagok piga 245 10 $a 連歌曲 悲歌 Title main entry: 1 245 00 $a Pi pa du zou qu ji 245 00 $a 琵琶独奏曲集 245 00 $a Shandong min jian qi yue ju xuan 245 00 $a 山東民間器樂曲選 245 00 $a Zhongguo zhu di du zou qu jing xuan 245 00 $a 中國竹笛獨奏曲精選 245 00 $a Ikuta-ryū sōkyoku senshū 245 00 $a 生田流箏曲選集 245 00 $a P’iri kuŭm chŏngakpo 245 00 $a 피리 口音 正樂譜 5.1D. -

Ro Musica Nipponia Nihon Ongaku Shudan 1988

RO MUSICA NIPPONIA NIHON ONGAKU SHUDAN 1988 日本音楽集団 ABOUT THE PRO MUSICA NIPPONIA Cities visited by the Pro Mttica Nlpponia (NIⅡ ON ONGAKU SIUDAN) 1972 EurO● (20 memb● rs) Chel,ti Brusselsi Colognei Berlin I Brno i Prague; The Nihon Ongaku Shudan knownin the West as Viennal Munich; Zagreb l BeOgrade: SombOri the Pro Musica Nipponia (formelly thc Ensemblc Provdiv:Sofia;Ca,ovo;Ruse;Craiova;Bucharest Nipponia), iS a grOup Of leading compOsers and top 1974 SOutheast Asia(18 nembers) rank musicians dcvoted lo the perormance of a wide Dlakarta l Denpasari saigOn i Manila ranging repertoire of clasical and modern contpOSi 1975 A‐ traⅢ a and New Zca]and(24 members) Vct The ottstanding tions iom bOth Japan and theヽ Perh: Adelaide, S,ancy i canberra i lrelbournei feattre of the ЯrOup is that music is perormcd Hobartiヽ Vellington i Auckland the traditional instruments of Japan The Pro 1976 Canada and U S A(6 7 members) ・ ″as Mtlsica Nipponia talSO Ca led [he Nippol,ia')ヽ Toronto; Ithaca l Richmond, Middlebury, New founded in 1964 with the expres intention of fOnnu York;Amher“ Washin,on:KnoxviJe Pit“ burgh lating a vital expretsiOn based upon ceJturies Old Ann Arboeri Chicagoi St Louis: ヽ4t Vernoni forms and instrumenヽ inTparably linkcd、 vitll tradi llllo:1lonolulu tional aesthetics and yet rsponsive to the spirit of ]978 Europe,Canada and U S A (26 members) the tim“ Old compositions have bcen re created Athena; I_ondon, Leipzigi Berlin i 14agdeburgi throu"vi■ d interpreta● On, ana new compOЫ ●ons Erurti Plauen i Dessau i Bucharesti Clu,, Satu incltlding -

281550-Sample.Pdf

Sample file Strings, Songs and Stories The Bard Colleges of Kozakura and Wa 1.00 Everything you need to perform in the traditional styles of Japan. By Ashley May & Isaac A. L. May DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, D&D, Wizards of the Coast, Forgotten Realms, Ravenloft, Eberron, the dragon ampersand, Ravnica and all other Wizards of the Coast product names, and their respective logos are trademarks of Wizards of the Coast in the USA and other countries. This work contains material that is copyright Wizards of the Coast and/or other authors. Such material is used with permission under the Community Content Agreement for Dungeon Masters Guild. This work was assembled using The GM Binder, a free tool provided by Iveld. All photos and artwork are in the public domain, sourced from Wikimedia Commons. All other original material in this work is copyright 2019 by Ashley May and Isaac A. L. May, and published under the Community Content Agreement for Dungeon Masters Guild. Sample file Introduction rom the land of Faerûn, a trade route known as The Golden Way leads to the far east. Most Faerûnian folk know only of the distand land of Kara-Tur by the silk, spices, and unique treasures that flow from the east. Rarely, a fighter known as a 'samurai' Fmay come their way, but most Faerûnians know little of what that means, beyond a particularly well-mannered warrior. What even fewer know is that beyond The Golden Way, beyond the land of Shou Lung, on the other side of the Celestial Sea, lay the unique and beautiful lands of Kozakura and Wa. -

9 Ways to Elevate Your Fue Playing

Eien Hunter-Ishikawa DRUMSET - TAIKO - SHINOBUE ! Performer - Educator - Composer 9 Ways to Elevate Your Fue Playing ! Fue is the broad Japanese word for flute, but this label is commonly used to refer to the shinobue (horizonal flutes made from the shino bamboo). In general, there are two main categories under which shinobue are sold: 1. koten joushi (also called hayashi bue or matsuri bue) are used in Japanese traditional and folk music, where the finger holes are uniform in size; 2. uta you (or uta bue) are tuned to the Western scale and the finger holes vary in size to accommodate this tuning. The number on the plugged end of the instrument designates the key – the higher the number, the higher the pitch and shorter the length – and each numerical increase raises the key by one half-step. For example, the number 6 fue is in B-flat major, while the number 7 is in B major and the number 5 is in A major. With its high-pitched projection and range of possible timbres, the shinobue is a natural partner to taiko and can substantially add life and variety to taiko and other ensembles. Leaning how to play fue will boost a taiko player’s musicianship because this new perspective provides better melodic awareness and listening skill. Here are 9 ways to help elevate your fue playing: ! 1. Own a quality instrument – there is no substitute for leaning on a proper instrument. While plastic or cheap bamboo fue are better than nothing, decent ones can be purchased for slightly over $100 and very good ones start at around $200.