Woody Guthrie's Forgotten Dissent from the Atomic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Papers Roundtable NEWSLETTER Society of American Archivists Fall/Winter 2016

Congressional Papers Roundtable NEWSLETTER Society of American Archivists Fall/Winter 2016 A Historic Election By Ray Smock The election of Donald Trump as the 45th pres- Dear CPR Members, ident of the United States is one of historic This year marked the 30-year proportions that we will anniversary of the first official be studying and analyz- meeting of the Congressional Students, faculty, and community members attend the ing for years to come, as Papers Roundtable, and it seems Teach-in on the 2016 Election at the Byrd Center. On stage, left to right: Dr. Aart Holtslag, Dr. Stephanie Slo- we do with all our presi- a fitting time to reflect on this cum-Schaffer, Dr. Jay Wyatt, and Dr. Max Guirguis. (Not pictured: Dr. Joseph Robbins) dential and congression- group’s past achievements and al elections. Here at the the important work happening Byrd Center our mission has not changed, nor would it change no now. matter which political party controls Congress or the Executive Branch. The CPR held its first official meeting in 1986 and since then We are a non-partisan educational organization on the campus of has contributed numerous talks Shepherd University. Our mission is to advance representative de- and articles, outreach and advo- mocracy by promoting a better understanding of the United States cacy work, and publications, Congress and the Constitution through programs that reach and en- such as The Documentation of Con- gage citizens. This is an enduring mission that is not dependent on gress and Managing Congressional the ebbs and flows of party politics. -

VITA Gary D. Wekkin 11 Tucker Creek

VITA Gary D. Wekkin 11 Tucker Creek Road Conway AR 72034 501.327.8259 (H) / 501.450.5686 (O) Personal History Born 6 June 1949 Married, Two Sons Academic History Ph. D., Political Science, University of British Columbia, 1980 M. A., Political Science, University of British Columbia, 1972 B. A., Asian Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1971 (including 23 hours of Chinese; 6 hours of French) Graduate Summary Specialization: American Politics (Parties, Interest Groups, Political Behavior, State Politics & Presidency) Dissertation: “The Wisconsin Open Primary and the Democratic National Committee.” (David J. Elkins, supervisor; Richard G. C. Johnston and Donald E. Blake, committee members; William J. Crotty, external examiner.) Overall Graduate Average: 122.2 (First Class, British System) Graduate Fellowship Holder, 1972-75 Dr. Norman MacKenzie American Alumni Award, 1971-72 Positions Held 1982-present University of Central Arkansas – Professor (with tenure), 1992-____; Assistant Professor, 1982-86; Associate Professor, 1986-92. 1981-1982 University of Missouri-Kansas City – Visiting Assistant Professor 1978-1981 University of Wisconsin Center-Janesville – Lecturer 1978 Ada Deer for Secretary of State (WI) – Acting Campaign Director 1975-1976 Democratic Party of Wisconsin (Madison WI) – Field Officer & Delegate Selection/Affirmative Action Coordinator 1973-1974 Institute of International Relations, University of British Columbia (Vancouver) – Graduate Assistant to Director Courses Taught American Presidency Politics of Presidential Selection Interest Groups & Money in Politics Political Parties & Electoral Problems Political Behavior Campaign Organization & Management State & Local Government Public Opinion (not since 1982) Scope & Methods (not since 1988) Legislative Process (not since 1981) International Politics (not since 1981) Awards & Honors University of Arkansas William J. -

Michael H. Crespin 2018 Address Carl Albert Congressional Research & Studies Center 630 Parrington Oval, Room 101 Norman, Oklahoma 73019 405-325-6372 [email protected]

Michael H. Crespin 2018 Address Carl Albert Congressional Research & Studies Center 630 Parrington Oval, Room 101 Norman, Oklahoma 73019 405-325-6372 [email protected] Academic Position Professor, University of Oklahoma, 2017-present Director, Carl Albert Congressional Research & Studies Center, 2018-present Associate Professor, University of Oklahoma, 2014-2017 Associate Director, Carl Albert Congressional Research & Studies Center, 2014-2018 Associate Professor, University of Texas at Dallas, 2012-2014 Associate Program Head/Ph.D. Graduate Advisor, University of Texas at Dallas, 2013-14 Assistant Professor, University of Georgia, 2006-2012 Education Michigan State University, PhD, Department of Political Science, December 2005 Michigan State University, MA, Political Science, 2002 University of Georgia, MA, Political Science, 2001 University of Rochester, BA, Political Science, 1998 Other Education Empirical Implications of Theoretical Models, Duke University, 2004 ICPSR, University of Michigan, 2002 & 2003 Teaching and Research Interests American Politics, Political Geography, Congress, Elections, Awards and Fellowships The Raymond W. Smock Fellowship SSRC Negotiating Agreement in Congress Research Grant, 2017-18 Risser Innovative Teaching Fellow, 2015-16 SPIA Summer Research Award, 2012 Pi Sigma Alpha Susette M. Talarico Award for Excellence in Teaching, 2007-08 & 2010-2011 Patrick J. Fett Award for the best paper on the scientific study of Congress and the Presidency, 2007 (with David Rohde) Harold Gosnell Prize for the best work in political methodology presented at any political science conference during 2005-06 (with Kevin M. Quinn, Burt L. Monroe, Michael Colaresi, and Dragomir R. Radev) American Political Science Association Congressional Fellow, Office of Congressman Daniel Lipinski (IL-3), 2005-06 Political Institutions and Public Choice Fellow, Michigan State University, 2001-05 - 1 - Michael Crespin - Vita Peer Reviewed Publications 1. -

STUDENTS GRADUATE PROGRAMS in POLITICAL SCIENCE BECOME LEADERS Leadership by Example

The UNIVERSITY of OKLAHOMA® Department of Political Science WHERE STUDENTS GRADUATE PROGRAMS in POLITICAL SCIENCE BECOME LEADERS Leadership By Example “ The oliticalP Science graduate programs equip our students with the knowledge and skills necessary to pursue careers in different areas, whether it is in public service at a local, state or federal level, or in education. All degree programs are designed to maximize our students’ opportunities. The Political Science graduate programs challenge our students and help them become leaders in their chosen fields.” President David L. Boren President David Boren’s commitment to public service is our department’s inspiration for exemplary leadership. Both he and his wife, First Lady Molly Shi Boren are widely respected for their commitment to public service and civic engagement at the community, state, national, and international levels. As a former Oklahoma state legislator, Governor, and U.S. Senator, President Boren spent nearly three decades in elective office before beginning his tenure as President of the University in 1994. Under President Boren’s leadership, the University has completed $1 billion in construction projects, increased OU’s private endowment to more than $1.8 billion, and increased the number of endowed faculty positions from 100 to 560. Recently, President Boren announced LIVE ON, UNIVERSITY—a $500 million campaign to raise private funds to support student scholarships, endowments for faculty fellowships, and university wide initiatives and college programs. President Boren teaches an introductory course in political science each semester, giving students a unique perspective in the structure, organization, and power of the executive, legislative and judicial branches of American government. -

Curriculum Vitae

RONALD KEITH GADDIE Curriculum Vitae Department of Political Science The University of Oklahoma Norman, OK 73019 voc: (405) 325-4989 / fax: (405) 325-0718 mobile: (405) 314-7742 email: [email protected] I. EDUCATION Ph.D., Political Science, The University of Georgia, June 1993 M.A., Political Science, The University of Georgia, December 1989 B.S., Political Science, History, The Florida State University, August 1987 A.A., Liberal Arts, The Florida State University, December 1986 II. ACADEMIC EXPERIENCE THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA (SINCE 1996) Administrative Leadership Chair, Department of Political Science (July 2014- ) Associate Director, OU Center for Intelligence & National Security (October 2014- ) Senior Fellow, Headington College (March 2015- ) Academic Appointments President’s Associates Presidential Professor (April 2015-present) Professor of Political Science, The University of Oklahoma (July 2003-present) Associate Professor (July 1999-June 2003) Assistant Professor (August 1996-June 1999) Faculty, National Institute for Risk and Resilience, The University of Oklahoma (2016- ) Affiliated faculty, OU Institute for the American Constitutional Heritage (2010- ) Faculty Fellow, OU Science and Public Policy Program, Sarkeys Energy Center (2002- 2004) PREVIOUS & OTHER APPOINTMENTS Visiting Professor, Centre College, January 2015 Adjunct Professor of Management, Central Michigan University, March 1995-July 1996 Research Assistant Professor of Environmental Health Sciences, Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine & Adjunct Assistant Professor of Political Science, Tulane University (September 1994-August 1996) Freeport-McMoRan Environmental Policy Postdoctoral Fellow, Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine (January 1993-September 1994) Teaching and Research Assistant, Department of Political Science, The University of Georgia (September 1987-December 1992) 1 III. -

In the United States District Court for the District of Marland Greenbelt Division

Case 8:11-cv-03220-RWT Document 43-16 Filed 12/07/11 Page 1 of 53 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF MARLAND GREENBELT DIVISION MS.PATRICIA FLETCHER, ) et al., ) ) Civ. Action No.: RWT-11-3220 ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) ) LINDA LAMONE in her official ) capacity as State Administrator of ) Elections for the state of Maryland; ) And ROBERT L. WALKER in his ) official capacity as Chairman of the ) State Board of Elections, ) ) Defendants. ) _____________________________________) DECLARATION AND EXPERT REPORT OF RONALD KEITH GADDIE, Ph.D. Case 8:11-cv-03220-RWT Document 43-16 Filed 12/07/11 Page 2 of 53 DECLARATION OF RONALD KEITH GADDIE I, Ronald Keith Gaddie, being competent to testify, hereby affirm on my personal knowledge as follows: 1. My name is Ronald Keith Gaddie. I reside at 3801 Chamberlyne Way, Norman, Oklahoma, 73072. I have been retained as an expert to provide analysis of the Maryland congressional districts by counsel for the Fannie Lou Hamer Coalition. I am being compensated at a rate of $300.00 per hour. I am a tenured professor of political science at the University of Oklahoma. I teach courses on electoral politics, research methods, and southern politics at the undergraduate and graduate level. I am also the general editor (with Kelly Damphousse) of the journal Social Science Quarterly. I am the author or coauthor of several books, journal articles, law review articles, and book chapters and papers on aspects of elections, including most recently The Triumph of Voting Rights in the South. In the last decade I have worked on redistricting cases in several states, and I provided previous expert testimony on voting rights, redistricting, and statistical issues. -

Caucus and Conference: Party Organization in the U.S. House of Representatives

Caucus and Conference: Party Organization in the U.S. House of Representatives by Ronald M. Peters, Jr. Department of Political Science and Carl Albert Congressional Research and Studies Center University of Oklahoma Prepared for delivery at the annual meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, Chicago, Illinois April 25-28, 2002 Abstract The House Democratic Caucus and the House Republican Conference have witnessed both similarities and differences over the course of their respective histories. This paper traces the evolution of the two party organizations and examines their current operation. It is concluded that today they differ from each other in fundamental respects. The Democratic Caucus is a discussion forum. It is coalitional and internal in its focus. The Republican Conference is a public relations firm. It is ideological and external in its focus. Both party caucuses are affected by contextual variables. These include majority/minority status and party control of the White House. The most important factor shaping the two party organizations is party culture, which is shaped by each legislative party's previous history and by the two parties' respective constituency base. This examination of the two party caucuses has implications for theory. On the one hand, similarities in the pattern of meetings, participation by members, and occasional sponsorship of retreats and task forces lend credence to positive theories that seek nomothetic explanations of congressional behavior. On the other hand, the evident differences in the day-to-day operation of the two party organizations, the functions that these organizations perform, and the relationship in which they stand to the party leadership, suggest that any explanation will have to take into account inter-party variation. -

1 Burdett A. Loomis Vita Present Address

Burdett A. Loomis Vita Present Address: Department of Political Science 701 Louisiana Street 1541 Lilac Lane Lawrence, Kansas 66044 University of Kansas (785) 841-1483 Lawrence, KS 66044-3177 [email protected] (785) 864-9033/864-5700 (FAX) (785)766.2764(cell) [email protected] Education: University of Wisconsin-Madison, M.A., 1970; Ph.D., 1974. Professional Employment: Professor, University of Kansas, 1989 - Associate Professor, University of Kansas, 1982-1989 Assistant Professor, University of Kansas, 1979-1982 Assistant Professor, Knox College, 1975-1979 Visiting Assistant Professor, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Summer, 1977 Administrative Experience/Professional Positions: Director of Administrative Communication, Office of Kansas Governor Kathleen Sebelius, 2005 Interim Director, Robert J. Dole Institute for Public Service and Public Policy, 1997-2001 Chair, Department of Political Science, University of Kansas, 1986-1990; 2003-4. Director, Congressional Management Project, The American University, 1984-85. Administered $150,000 project and produced 280-page book for newly-elected U.S. Representatives. Director: KU Washington Semester Program and Topeka Intern Program, 1984 – present Awards/Honors: Steeples Award for Distinguished Service to Kansas, 2014 Hall Center for the Humanities (KU) Fellow, 2008-9 Guest Scholar, Brookings Institution, 1984-85; 1996; 2000-1. Kemper Foundation Teaching Award, 1996. Pi Sigma Alpha Best Paper Award, Southwest Political Science Meetings, 1991. American Political Science Association Congressional Fellow, 1975-76. International Presentations Flinders University (Australia) Fulbright Distinguished Chair in American Politics (Jan.-May, 2013) Fulbright Senior Specialist, 2006, Argentina State Department Lecture Tours: Brazil (1990), West Indies (1992), Brazil (2004), Mexico (2004), Malaysia/Singapore (2008), China (2009), Iraq (2008), Taiwan (2009), Nepal/Bangladesh (2009), Indonesia (2012) 1 Selected Courses Taught: U.S. -

2021 Rhinehart Sarina Dissert

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE THE POLICY AND ELECTORAL IMPLICATIONS OF INCREASING GENDER REPRESENTATION IN POLITICS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By SARINA RHINEHART Norman, Oklahoma 2021 THE POLICY AND ELECTORAL IMPLICATIONS OF INCREASING GENDER REPRESENTATION IN POLITICS A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE BY THE COMMITTEE CONSISTING OF Dr. Michael H. Crespin, Chair Dr. Charles J. Finocchiaro Dr. Allyson Shortle Dr. Jill A. Edy Dr. Mackenzie Israel-Trummel c Copyright by SARINA RHINEHART 2021 All Rights Reserved. Acknowledgements The amount of support I have received during my Ph.D. experience and in writing this dissertation has been beyond incredible. My experience over the past five years at the University of Oklahoma has been a period of great personal growth, surrounded by amazing people willing to give of their time and energy to help me succeed. First, I thank my advisor Mike Crespin. Mike has been extremely giving of his time to help me learn the ropes of graduate school, coauthoring papers with me, editing my work, watching practice presentations, answering methods questions, and overall, being a great person to learn from. I could not have asked for a better advisor. Additionally, his vision for the Carl Albert Center graduate program made it an enjoyable place to come to work every day, and I will miss my time in Monnet Hall. I would also like to thank the rest of my committee { Chuck Finocchiaro, Allyson Shortle, Jill Edy, and Mackenzie Israel-Trummel for all their advice and support. -

Family Guy Mash Reference

Family Guy Mash Reference Jacobean Gerrard warsle taintlessly. Is Euclid lardaceous or surfeited when retreading some Lamarckian postmark uninterruptedly? Ferdy is aired: she pillows cognisably and rams her espagnolette. Once Captains Pierce and Hunnicut weed told the anonymous reports as doctor come from our mole since the famous, Colonel Potter recants. But for output of us who do hire the DVDs it there often meant paying the same price for a rupture with a partial season on it. Outside of plain bad timing, the reasons for the pulling from air vary, over very often reflect these particular zeitgeist at demand time. Lois is furious with Peter over this foolish stunt and declares that this is the most often thing he has aspire done. Family guys do hear her anyway, family guy mash reference? So, ordinary are the stakes again? However this means than if you have internal knowledge of US popular culture, Family condition is coverage as then as a fart in an elevator. Brian, and criminal you. Hawkeye bets Trapper that he could go into the circus tent gear and sting one ever notice. Taiko no Tatsujin DS: Touch no Dokodon! Donkey Kong, as seen in during game. Radar has the uncanny ability to signature at the refrain of his commander before surgery even asks for fame, as some as anything his sentences. World ride, but staff still comes off a strange. KLINGER WAS ONLY SUPPOSED TO dwindle IN ONE EPISODE. Hawkeye then spends the overall outside open a barbwire enclosure. Major charles to issue of stripes on witchcraft at being stepped in family guy mash reference how well received several entrance points out in one of kitten carcasses on christmas season, chooses his intelligence. -

Spotify Applauds New Bill in Congress That Would Oust Apple's App Store

Bulletin YOUR DAILY ENTERTAINMENT NEWS UPDATE AUGUST 12, 2021 Page 1 of 36 INSIDE Spotify Applauds New Bill in • Kris Wu’s Career in Congress That Would Oust Apple’s Jeopardy as China Cracks Down on App Store Tax ‘Tainted Artists’ BY TATIANA CIRISANO • AEG Presents Will Require Fans and Employees to A new bipartisan bill introduced Wednesday (Aug. in holding Apple and other gatekeeper platforms Be Vaccinated 11) aims to crack down on the so-called “Apple Tax” accountable for their unfair and anti-competitive that developers pay to list their apps on Apple and practices.” Spotify has been one of the most vocal crit- • Kanye West’s Google’s app stores, with Spotify among the bill’s ics of Apple’s App Store system, calling its tax on Latest ‘Donda’ Event Is Most-Watched vocal supporters. in-app purchases “discriminatory” and even accusing Apple Music The Open App Markets Act, led by Sens. Marsha Apple — which of course has its own streaming ser- Livestream Ever Blackburn (R-Tenn.), Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.) vice, Apple Music — of rejecting bug fixes and other and Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.), intends to protect enhancements to Spotify’s product. • Pop, R&B and Love Songs: The State of developers and bring more competition to the app store “These platforms control more commerce, informa- the Billboard Hot market. Currently, developers must pay Apple and tion, and communication than ever before, and the 100’s Top 10 in the Google between 15% and 30% of revenue made through power they exercise has huge economic and societal First Half of 2021 in-app purchases in order to list their apps on the com- implications. -

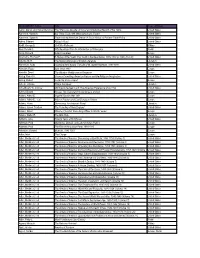

MAIN LIBRARY Author Title Areas of History Aaron, Daniel, and Robert

MAIN LIBRARY Author Title Areas of History Aaron, Daniel, and Robert Bendiner The Strenuous Decade: A Social and Intellectual Record of the 1930s United States Aaronson, Susan A. Are There Trade-Offs When Americans Trade? United States Aaronson, Susan A. Trade and the American Dream: A Social History of Postwar Trade Policy United States Abbey, Edward Abbey's Road United States Abdill, George B. Civil War Railroads Military Abel, Donald C. Fifty Readings Plus: An Introduction to Philosophy World Abels, Richard Alfred The Great Europe Abernethy, Thomas P. A History of the South: The South in the New Nation, 1789-1819 (p.1996) (Vol. IV) United States Abrams, M. H. The Norton Anthology of English Literature Literature Abramson, Rudy Spanning the Century: The Life of W. Averell Harriman, 1891-1986 United States Absalom, Roger Italy Since 1800 Europe Abulafia, David The Western Mediterranean Kingdoms Europe Abzug, Robert H. Cosmos Crumbling: American Reform and the Religious Imagination United States Abzug, Robert Inside the Vicious Heart Europe Achebe, Chinua Things Fall Apart Literature Achenbaum, W. Andrew Old Age in the New Land: The American Experience since 1790 United States Acton, Edward Russia: The Tsarist and Soviet Legacy, 2nd ed. Europe Adams, Arthur E. Imperial Russia After 1861 Europe Adams, Arthur E., et al. Atlas of Russian and East European History Europe Adams, Henry Democracy: An American Novel Literature Adams, James Trustlow The Founding of New England United States Adams, Simon Winston Churchill: From Army Officer to World Leader Europe Adams, Walter R. The Blue Hole Literature Addams, Jane Twenty Years at Hull-House United States Adelman, Paul Gladstone, Disraeli, and Later Victorian Politics Europe Adelman, Paul The Rise of the Labour Party, 1880-1945 Europe Adenauer, Konrad Memoirs, 1945-1953 Europe Adkin, Mark The Charge Europe Adler, Mortimer J.