Transportation Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Town Council Gives Approval to Proposal for Three-Day-A-Week Free Parking

7= HOW TO UT THI UADIR=r Just Fill in the Form On Page 16 And Return It to Us! —Serving the Town Since 1890 — UPS4KM 232-4407 r iim p»unwm<m.Nj. Thursday, October 7,1993 FORTY CENTS CHAMBER, MAINSTREET ADVANCE PLAN FOR HOUDAY SHOPPERS Town Council Gives Approval to Proposal For Three-Day-A-Week Free Parking Maximum of Three Hours Probably Would Be Allowed at the Beginning or End of Week From Thanksgiving to Christmas; Second Senior Citizen Housing Complex Will Pay 6 Per Cent of Revenues to Town If It Can Afford Fee By ROBERT R. FASZCZEWSKI proved too confusing and ineffective. meters on Thursday at 9 a.m. and taken to meet the fee, which would be evaluated Sptcialb Wrlitm/ornt WulfltUUadir The two business groups, he noted, off on Sunday morning. year-to-year, Town Attorney Charles H. Holiday shoppers in Westfield' s central wanted to place bags over the meters Downtown Manager, Mrs. Michele Brandt said, the fee would be waived. business district will be able to park, for form Thursday through Saturday in order Picou, of the MainSlreet Committee, The burden wou Id be on the developer, free at meters i n the di strict for three days to have shoppers take advantage of four added her group is planning a public he noted, to provide the town with facts to a week between Thanksgiving and promotions planned by the Chamber and relations program with merchants to justify a waiver from the fee. Christmas thanks to a plan proposed by the MainStrect group during die holidays. -

Bikesharing and Bicycle Safety Department of Transportation MTI Report 12-02MTI Report

MTI Funded by U.S. Department of Services Transit Census California of Water 2012 Transportation and California Bikesharing and Bicycle Safety Department of Transportation MTI ReportMTI 12-02 MTI Report 12-54 December 2012 MINETA TRANSPORTATION INSTITUTE MTI FOUNDER Hon. Norman Y. Mineta The Mineta Transportation Institute (MTI) was established by Congress in 1991 as part of the Intermodal Surface Transportation Equity Act (ISTEA) and was reauthorized under the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st century (TEA-21). MTI then successfully MTI BOARD OF TRUSTEES competed to be named a Tier 1 Center in 2002 and 2006 in the Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users (SAFETEA-LU). Most recently, MTI successfully competed in the Surface Transportation Extension Act of 2011 to Founder, Honorable Norman Joseph Boardman (Ex-Officio) Diane Woodend Jones (TE 2016) Michael Townes* (TE 2017) be named a Tier 1 Transit-Focused University Transportation Center. The Institute is funded by Congress through the United States Mineta (Ex-Officio) Chief Executive Officer Principal and Chair of Board Senior Vice President Department of Transportation’s Office of the Assistant Secretary for Research and Technology (OST-R), University Transportation Secretary (ret.), US Department of Amtrak Lea+Elliot, Inc. Transit Sector, HNTB Transportation Centers Program, the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans), and by private grants and donations. Vice Chair Anne Canby (TE 2017) Will Kempton (TE 2016) Bud Wright (Ex-Officio) Hill & Knowlton, Inc. Director Executive Director Executive Director OneRail Coalition Transportation California American Association of State The Institute receives oversight from an internationally respected Board of Trustees whose members represent all major surface Honorary Chair, Honorable Bill Highway and Transportation Officials transportation modes. -

RR-564 Part 2

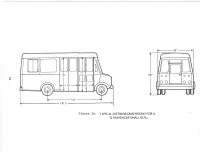

-------~---- -----~ __ _...: ___ ~--".~· ·~· ~~· ~··_ _:__~·~·~----~. 94" I _::\ 'r-'( 1~\ 107'' D 0 0 "" 0 0 00 O_Q JJJJ lUl t«--------125"------»t 1---------2105''----------""'1 Figure 28. TYPICAL EXTERIOR DIMENSIONS FOR A 12 PASSENGER SMALL BUS. / / 7 Wheel -------- f--1 36" Chair r -~ L ( ) .--- f_j 1\. \. '- 485'' '-- '-- 1~" 86" 129" I/ / 3b" --------- Lift \.. \.. r '/'/ I / / I I Wheel Lr- -------- Chair 1---' r -~ 45" L ,--- ,---- \.. (~ '-- '-- Wheel I/ / Chair ---· 30"-- Lift \.'\. \.. t Figure 29. TYPICALINTERIORDIMENSIONSANDSEATING ARRANGEMENTS FOR A 12 PASSENGER SMALL BUS. 52 90"==:1 £ _"'\ JUOI JQUl BBBB 64" 79" 0 D 0 (QQ] "'"\ 107" IOOI 50"-~---+ 1+24"~ \ ,__, ~ . ~ lJ1 I~ lr'l ~ 1 w ,.. ... - 76" -: 163" ' 262" Figure 30. TYPICAL EXTERIOR DIMENSIONS FOR A 20 PASSENGER SMALL BUS. c::::J =aCJ ··I- ······· 36" 86" 186" 14" ... I- . ..... 36" I,P" II = c::§bo Wheel Wheel ·- " ...... Chair Chair oo Jl Jl :·- '' ..... ·-· : Lift ?"'" Figure 31. TYPICAL INTERIOR DIMENSIONS AND SEATING ARRANGEMENTS FOR A 20 PASSENGER SMALL BUS. 54 TABLE 17 DIMENSIONS FOR VANS, MODIFIED VANS AND SMALL BUSES (1980 VEHICLES) Overall Vans Modified vans Small Buses Length (ins) 178 - 227 220 - 227 233 - 280 Width (ins) 80 80 - 94.5 80 96 Height (ins) 80 - 84 101 - ll5* 93.5 - ll7 Interior Length (ins)** 91 - 137 131 - 137 130 - 220 Width (ins) 69 - 71 69 - 82 79 90 Headroom (ins) 52 - 54 64 - 74 63 78 GVW (lbs) 6,050 - 8,550 9,000 10,250 - 18,000 Wheelbase (ins) llO - 138 127 - 138 125 - 167 Seating Capacity 5 - 15 9 - 16 12 22 *Higher value generally indicates the addition of air conditioning mounted on the roof. -

Online Version of the Questions (Updated Regularly): Q: Will Motorcyclists Be Able to Lane Share Anywhere?

Online version of the questions (updated regularly): https://laneshareoregon.com/#faqs Q: Will motorcyclists be able to lane share anywhere? No. Only under the limited conditions proposed in the bill, summarized below. Traffic on the road: must be stopped, or moving at 10 miles per hour or less The rider: may travel no more than 10 miles per hour faster than traffic must not impede the normal and reasonable movement of traffic must safely merge with traffic, if traffic speed exceeds 10 miles per hour Riders cannot lane share: between a traffic lane and the curb and bicycle lane (on either side) between a traffic lane and a row of parked vehicles (on either side) in a school zone Riders should also use common sense when lane sharing, and err on the side of caution: "If you can't fit, don't split". The California Highway Patrol has defined guidelines for safe lane sharing. Q: Is lane sharing dangerous for pedestrians and bicyclists? Not lane sharing under HB2314. HB2314 legalizes lane sharing only on roads with posted speeds of 50 mph or greater: highways and freeways. Most people don’t walk or bicycle on or across these roads, even if they’re allowed to. Also, under HB2314 motorcycles may not lane-share on the right hand side of the right hand lane, next to the curb, shoulder or bicycle lane. HB2314 was written this way to give additional protection to pedestrians and bicyclists. Commenting on the specific constraints in HB2314, Portland’s Bureau of Transportation wrote “our most serious concerns of threats to pedestrian and bike safety are addressed”. -

Lane Splitting Tips

Sven Miller, Commander Contact: Fran Clader Office of Community Outreach & Media Relations Director of Communications 601 North 7th Street, Sacramento, CA 95811 (916) 843-3310 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE September 27, 2018 18-27 CHP ANNOUNCES LANE SPLITTING TIPS SACRAMENTO, Calif. – Lane splitting is a privilege enjoyed by California motorcyclists. With this freedom comes a greater responsibility for motorcyclists and drivers to share the road and create a safer highway environment. In 2016, Governor Edmund G. Brown, Jr. signed California Assembly Bill 51, which defined motorcycle lane splitting and authorized the California Highway Patrol (CHP) to develop educational safety tips. Through a deliberative process and in consultation with the California Department of Motor Vehicles, the California Department of Transportation, the Office of Traffic Safety, and several motorcycle safety organizations, the CHP has finalized lane splitting tips. “Although lane splitting is legal in California, motorcyclists are encouraged to exercise extreme caution when traveling between lanes of stopped or slow-moving traffic,” said CHP Commissioner Warren Stanley. “Every rider has the ultimate responsibility for their own decision making and safety.” These general safety tips are provided to assist you when riding; however, they are not guaranteed to keep you safe: • Consider the total environment when you are lane splitting (this includes the width of lanes, the size of surrounding vehicles, as well as current roadway, weather, and lighting conditions). • Danger increases at greater speed differentials. • Danger increases as overall speed increases. • It is typically safer to split between the far left lanes than between the other lanes of traffic. • Try to avoid lane splitting next to large vehicles (big rigs, buses, motorhomes, etc.). -

Page 1 of 32 VEHICLE RECALLS by MANUFACTURER, 2000 Report Prepared 1/16/2008

Page 1 of 32 VEHICLE RECALLS BY MANUFACTURER, 2000 Report Prepared 1/16/2008 MANUFACTURER RECALLS VEHICLES ACCUBUIL T, INC 1 8 AM GENERAL CORPORATION 1 980 AMERICAN EAGLE MOTORCYCLE CO 1 14 AMERICAN HONDA MOTOR CO 8 212,212 AMERICAN SUNDIRO MOTORCYCLE 1 2,183 AMERICAN SUZUKI MOTOR CORP. 4 25,023 AMERICAN TRANSPORTATION CORP. 5 1,441 APRILIA USA INC. 2 409 ASTON MARTIN 2 666 ATHEY PRODUCTS CORP. 3 304 B. FOSTER & COMPANY, INC. 1 422 BAYERISCHE MOTOREN WERKE 11 28,738 BLUE BIRD BODY COMPANY 12 62,692 BUELL MOTORCYCLE CO 4 12,230 CABOT COACH BUILDERS, INC. 1 818 CARPENTER INDUSTRIES, INC. 2 6,838 CLASSIC LIMOUSINE 1 492 CLASSIC MANUFACTURING, INC. 1 8 COACHMEN INDUSTRIES, INC. 8 5,271 COACHMEN RV COMPANY 1 576 COLLINS BUS CORPORATION 1 286 COUNTRY COACH INC 6 519 CRANE CARRIER COMPANY 1 138 DABRYAN COACH BUILDERS 1 723 DAIMLERCHRYSLER CORPORATION 30 6,700,752 DAMON CORPORATION 3 824 DAVINCI COACHWORKS, INC 1 144 D'ELEGANT CONVERSIONS, INC. 1 34 DORSEY TRAILERS, INC. 1 210 DUTCHMEN MANUFACTURING, INC 1 105 ELDORADO NATIONAL 1 173 ELECTRIC TRANSIT, INC. 1 54 ELGIN SWEEPER COMPANY 1 40 E-ONE, INC. 1 3 EUROPA INTERNATIONAL, INC. 2 242 EXECUTIVE COACH BUILDERS 1 702 FEATHERLITE LUXURY COACHES 1 83 FEATHERLITE, INC. 2 3,235 FEDERAL COACH, LLC 1 230 FERRARI NORTH AMERICA 8 1,601 FLEETWOOD ENT., INC. 5 12, 119 FORD MOTOR COMPANY 60 7,485,466 FOREST RIVER, INC. 1 115 FORETRAVEL, INC. 3 478 FOURWINNS 2 2,276 FREIGHTLINER CORPORATION 27 233,032 FREIGHTLINER LLC 1 803 GENERAL MOTORS CORP. -

Hvy Dty Veh & Eng Res. Guide

The U.S. Department Of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency And Renewable Energy’s National Alternative Fuels Hotline Heavy-Duty Vehicle and Engine Resource Guide This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, expressed or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. FOR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION CONTACT THE HOTLINE 800-423-1DOE • 703-528-3500 FAX: 703-528-1953 EMAIL: [email protected] Introduction Engine manufacturers are moving forward when it comes to alternative fuel engine technology. This model year (MY96), heavy-duty engine manufacturers are offering a number of natural gas models with additional models nearing production. Electric vehicle manufacturers have several products available with new models nearing completion. Although Caterpillar is the only manufacturer offering propane as a fuel option, Detroit Diesel Corp. (DDC) will be demonstrating a prototype model in 1996, and Cummins will release a model within MY96. Many manufacturers are offering natural gas engines in response to California Air Resource Board’s strict bus emission standards which are effective MY96. -

Motor Vehicle Make Abbreviation List Updated As of June 21, 2012 MAKE Manufacturer AC a C AMF a M F ABAR Abarth COBR AC Cobra SKMD Academy Mobile Homes (Mfd

Motor Vehicle Make Abbreviation List Updated as of June 21, 2012 MAKE Manufacturer AC A C AMF A M F ABAR Abarth COBR AC Cobra SKMD Academy Mobile Homes (Mfd. by Skyline Motorized Div.) ACAD Acadian ACUR Acura ADET Adette AMIN ADVANCE MIXER ADVS ADVANCED VEHICLE SYSTEMS ADVE ADVENTURE WHEELS MOTOR HOME AERA Aerocar AETA Aeta DAFD AF ARIE Airel AIRO AIR-O MOTOR HOME AIRS AIRSTREAM, INC AJS AJS AJW AJW ALAS ALASKAN CAMPER ALEX Alexander-Reynolds Corp. ALFL ALFA LEISURE, INC ALFA Alfa Romero ALSE ALL SEASONS MOTOR HOME ALLS All State ALLA Allard ALLE ALLEGRO MOTOR HOME ALCI Allen Coachworks, Inc. ALNZ ALLIANZ SWEEPERS ALED Allied ALLL Allied Leisure, Inc. ALTK ALLIED TANK ALLF Allison's Fiberglass mfg., Inc. ALMA Alma ALOH ALOHA-TRAILER CO ALOU Alouette ALPH Alpha ALPI Alpine ALSP Alsport/ Steen ALTA Alta ALVI Alvis AMGN AM GENERAL CORP AMGN AM General Corp. AMBA Ambassador AMEN Amen AMCC AMERICAN CLIPPER CORP AMCR AMERICAN CRUISER MOTOR HOME Motor Vehicle Make Abbreviation List Updated as of June 21, 2012 AEAG American Eagle AMEL AMERICAN ECONOMOBILE HILIF AMEV AMERICAN ELECTRIC VEHICLE LAFR AMERICAN LA FRANCE AMI American Microcar, Inc. AMER American Motors AMER AMERICAN MOTORS GENERAL BUS AMER AMERICAN MOTORS JEEP AMPT AMERICAN TRANSPORTATION AMRR AMERITRANS BY TMC GROUP, INC AMME Ammex AMPH Amphicar AMPT Amphicat AMTC AMTRAN CORP FANF ANC MOTOR HOME TRUCK ANGL Angel API API APOL APOLLO HOMES APRI APRILIA NEWM AR CORP. ARCA Arctic Cat ARGO Argonaut State Limousine ARGS ARGOSY TRAVEL TRAILER AGYL Argyle ARIT Arista ARIS ARISTOCRAT MOTOR HOME ARMR ARMOR MOBILE SYSTEMS, INC ARMS Armstrong Siddeley ARNO Arnolt-Bristol ARRO ARROW ARTI Artie ASA ASA ARSC Ascort ASHL Ashley ASPS Aspes ASVE Assembled Vehicle ASTO Aston Martin ASUN Asuna CAT CATERPILLAR TRACTOR CO ATK ATK America, Inc. -

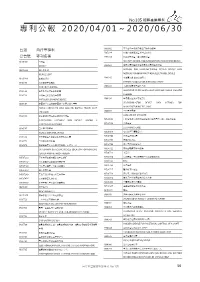

專利公報2020/04/01~2020/06/30

No.105 相關產業專利 專利公報 2020/04 /01 ~ 2020/ 06/ 3 0 台灣 自行車專利 I695802 可供自行車收納之組合式攜帶箱結構 I695924 圓筒鎖之保護裝置及其組裝方法 公告號 專利名稱 I695954 防止犯罪裝置、資訊處理裝置 D205332 自行車 SECURITY DEVICE AND INFORMATION PROCESSING DEVICE BICYCLE I696023 顯示裝置的製造方法及電子裝置的製造方法 D205335 自行車座墊 METHOD FOR MANUFACTURING DISPLAY DEVICE AND BICYCLE SEAT METHOD FOR MANUFACTURING ELECTRONIC DEVICE I696205 可提高安全性的電池模組 D205426 車燈之部分 BATTERY MODULE FOR IMPRVING SAFETY I696558 用於腳踏車的輪轂 HUB FOR A BICYCLE I696223 半導體裝置及其製造方法 I696559 無內胎之自行車輪胎結構 SEMICONDUCTOR DEVICE AND MANUFACTURING METHOD THEREOF I696563 自行車之防鎖死煞車機構 I696293 半導體裝置及其製造方法 ANTI-LOCK BRAKING DEVICE SEMICONDUCTOR DEVICE AND METHOD FOR I696564 鎖固結構及具有該鎖固結構的電動自行車架 MANUFACTURING THE SAME FIXING STRUCTURE AND ELECTRIC BICYCLE FRAME WITH I696333 一種直流電機 THE SAME A DC MOTOR-DYNAMO I696566 懸吊總成及具有懸吊總成之自行車 M596556 用於控制顯示裝置之無線控制模組及具方向指示功能之背包 SUSPENSION ASSEMBLY AND BICYCLE HAVING A SUSPENSION ASSEMBLY M596568 升降裝置 ELEVATING DEVICE I696567 自行車控制裝置 BICYCLE CONTROL DEVICE M596644 多功能輕型運動器材 M596706 自行車輻條結構 I696569 用於腳踏車前鏈輪上鏈條的移位裝置 M596707 無聲花轂結構 I696772 自行車用碟煞碟盤 I696978 偵測腳踏車位置以通知伺服器之系統及方法 M596708 自行車花轂離合結構 SYSTEM FOR DETECTING BICYCLE LOCATION FOR NOTICING M596721 前輪自動歸正煞車結構 SERVER AND METHOD THEREOF M596722 水壺架 M597189 用於自行車輪圈組裝之中空鉚釘 M596724 行動裝置之車用安裝配件組及其輔助結構 M597192 自行車輻條切斷與搓牙機結構 M596725 鈴鐺 M597241 自行車或機車之外驅電動機構 M596726 自行車鈴 M597247 自行車前貨架 M596727 整合線式固定座 M597249 具施力控制變速功能之自行車 M596728 自行車之踏踩間距調整結構 M597456 公共腳踏車租借系統 M596872 儲能元件的使用壽命的估算系統 M597488 兩輪車輛停車位自動搜尋裝置 M596883 全電壓萬用型充電器 D205137 攜車架(七) M596950 車輛速度提醒及照相裝置 BIKE CARRIER (7) D204972 輪胎 D205150 -

Cost Evaluation for Nine Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards

TL DOT HS- 805 320 242 . H3 82 COST EVALUATION FOR NINE FEDERAL v . 6 MOTOR VEHICLE STANDARDS VOLUME VI FMVSS 220, 221, & 222 M. R. Harvey DEPARTMENT of J. A. Lesczhik transportation R. F. McLean 1 4 1980 De Lorean Motor Company JUL 2401 Elliott Street library Troy, Michigan 48084 J Contract No. D0T-HS-8-02015 Contract Amt. $332,007 NOVEMBER 1979 FINAL REPORT This document is available to the U.S. public through the National Technical Information Service, Springfield, Virginia 22161 Prepared For U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION National Highway Traffic Safety Administration Washington, D.C. 20590 This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Govern- ment assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. 5 O.’P- T*cImmc«I K fr> P»c——tt«— P /• *' 2. C t»tiw Ac<*l»i*a Mo. 1. i Ho. s.L J)OT-HS-805 320 4pr.»W rnU J. !•>••• £>•*• COST EVALUATION FOR NINE FEDERAL MOTOR VEHICLE NOVEMBER 1979 SAFETY STANDARDS Vol. VI 4. 7«Imm| CWp.. miM Cat* $. —if Of|«w itiiMi B >»•»! Mo. 7 . AvAa/a M.R. GARVEY, J. A. LESCZHIK, R.F. McLEAN *. PwMkt Ot,s>i ukM K«m m* «<»IH 10. U«.l N. (THAIS) DE L0REAN MOTOR COMPANY RESEARCH & ENGINEERING DIVISION 1 I Conflict 04 G'tni N • 2401 ELLIOTT STREET D0T-HS- 8-0201 TROY. MICHIGAN 48084 13. Tjth ol R sport ond P *r«od Cov«r*^ FINAL REPORT DEMT^rOF^^RWlON 10/78 - 11/79 NATIONAL HIGHWAY TRAFFIC SAFETY ADMINISTRATION 400 SEVENTH STREET S.W. -

CNG As a Transit Bus Fuel

TheThe TransitTransit BusBus NicheNiche MarketMarket ForFor AlternativeAlternative Fuels:Fuels: ModuleModule 3:3: OverviewOverview ofof CompressedCompressed NaturalNatural GasGas asas aa TransitTransit BusBus FuelFuel CleanClean CitiesCities CoordinatorCoordinator ToolkitToolkit PreparedPrepared byby TIAXTIAX LLC,LLC, IrvineIrvine OfficeOffice DecemberDecember 20032003 TIAX LLC One Park Plaza, 6th Floor Irvine, California 92614 949-833-7131 / [email protected] Options for Natural Gas Fueling in Transit • Compressed Natural Gas (CNG) – Pipeline natural gas: methane with other hydrocarbons – Pressurized to 3,600 psi – Fueling accomplished by pressure transfer to vehicle – About 12% of transit buses in the U.S. now use conventional CNG – Largest users include LACMTA, MARTA, NY DOT, Pierce Transit, Washington D.C. (WMATA), Cleveland, Sacramento • Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) – Nearly pure methane (~98%) liquefied at very low temperatures – Liquid transfer to vehicle – Largest users are Phoenix, Orange County (CA), Dallas, and Tempe – Newer users include Santa Monica, Long Beach • LNG to CNG (“LCNG”) – Vaporized LNG (also nearly pure methane) – Liquid to gas conversion, then pressure transfer to vehicle – Sun Metro, OmniTrans, others use this approach Document Code 1 Methane Content in Pipeline Natural Gas Varies Regionally Methane Molecule Typical Composition of Pipeline Natural Gas What are the Implications of the Resulting CNG Fuel Quality Variations? • CNG with lower methane content (higher levels of ethane, propane, or butane) has resulted in some adverse affects on heavy-duty NG engine performance (e.g., misfire, stumble and underrated operation, engine knock, overheating) • However, today’s lean-burn closed-loop NG engines for transit (e.g., C Gas Plus and DDC S50G) are better able to tolerate and compensate for variations • Compromises in emissions performance have been found to be modest Document Code 2 Numerous OEMs Offer Natural Gas Transit Buses and Paratransit Vehicles Natural Gas Bus Manufacturer Models Available Champion Bus, Inc. -

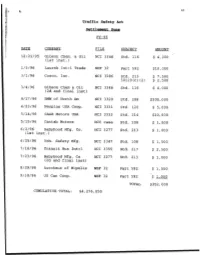

To View All Safety Act Settlements from 1996-2009

2 41 Traffic Safety Act Settlement Sums FY-96 -DATE COMPANY FILE SUBJECT AMOUNT 12/21/95 Gibson Chem. & Oil NCI 3346 Std. 116 $ 4,000 (1st inst.) 1/3/96 Laurek Int=l Trade NEF 32 Part 592 $10,000 3/1/96 Cosco, Inc. NCI 3286 Std. 213 $ 7,500 30119 (c)(2) $ 2,500 3/4/96 Gibson Chem & Oil NCI 3346 Std. 116 $ 4,000 (2d and final inst) 4/17/96 BMW of North Am NCI 3320 Std. 208 $300,000 4/23/96 Neoplan USA Cow. NCI 3331 Std. 120 $ 5,000 5/14/ 96 SAAB Motors USA NCI 3333 Std. 214 $10,000 5/15/96 Cantab Motors NCC case Std. 208 $ 1,000 6/2/96 Babyhood Mfg. Co. NCI 3277 Std. 213 $ 1,000 (1st inst.) 6/25/96 Veh. Safety Mfg. NCI 3347 Std. 108 $ 1,500 7/16/96 Transit Bus Int=l NCI 3355 Std. 217 $ 2,500 7/23/96 Babyhood Mfg. Co NCI 3277 Std. 213 $ 1.000 (2d and final inst) 8/29/96 Autohaus of M=polis NEF 32 Part 592 $ 1,000 9/30/96 US Car Corp. NEF 32 Part 592 $ 1,000 TOTAL $352,000 CUMULATIVE TOTAL: $4,276,050 42 I Traffic Safety Act Settlement Sums FY-97 -DATE COMPANY FILE SUBJECT AMOUNT 10/96 American Honda EA9 4 - 03 5 30118(c) (1) $ 50,000 Motor Co. 30120 12/11/96 Motorsport Imports Sec. 591.8(e) 159,126 1/2/97 Cosco, Inc. NCI 3358 Std. 213 5,000 1/15/97 Takata Motor EA94-03 6 30118(c) (1) cow.