Transit Infrastructure and the Isthmus Megaproject

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zapotec Empire an Empire Covering 20 000 Sq

1 Zapotec Empire an empire covering 20 000 sq. km. This empire is thought to have included the Cen- ARTHUR A. JOYCE tral Valleys (i.e., the Valleys of Oaxaca, Ejutla, University of Colorado, USA and Miahuatlán) and surrounding areas such as the Cañada de Cuicatlán as well as regions to the east and south extending to the Pacific Archaeological and ethnohistoric evidence coastal lowlands, particularly the lower Río from Oaxaca, Mexico, suggests that Zapo- Verde Valley. These researchers argue that tec-speaking peoples may have formed small Monte Albán’s rulers pursued a strategy of empires during the pre-Hispanic era (Joyce territorial conquest and imperial control 2010). A possible empire was centered on through the use of a large, well-trained, and the Late Formative period (300 BCE–200 CE) hierarchical military that pursued extended city of Monte Albán in the Oaxaca Valley. campaigns and established hilltop outposts, The existence of this empire, however, has garrisons, and fortifications (Redmond and been the focus of a major debate. Stronger Spencer 2006: 383). Evidence that Monte support is available for a coastal Zapotec Albán conquered and directly administered Empire centered on the Late Postclassic outlying regions, however, is largely limited – (1200 1522 CE) city of Tehuantepec. to iconographic interpretations of a series of Debate concerning Late Formative Zapotec carved stones at Monte Albán known as the imperialism is focused on Monte Albán and “Conquest Slabs” and debatable similarities its interactions with surrounding regions. in ceramic styles among these regions (e.g., Monte Albán was founded in c.500 BCE on Marcus and Flannery 1996). -

Opportunities for Port Development and Maritime Sector in Mexico

Opportunities for Port Development and Maritime sector in Mexico Commissioned by the Netherlands Enterprise Agency Report by Marko Teodosijević - Embassy of the Netherlands in Mexico Opportunities for Port Development and Maritime sector in Mexico Investment opportunities in the Port Development Sector Early 2019 Preface In this report current and future business opportunities in the Mexican port development sector are identified. This report is the product of a detailed examination of Mexico’s plans for the development of its ports and maritime sector. The aim of the report is to map business opportunities for Dutch companies that operate in this sector and want to collaborate in Mexico’s sustainable port development programs. It is the objective of the Dutch Embassy to promote a mutually beneficial collaboration between Mexico and The Netherlands in the context of Mexico’s ambitious drive forward in the development of its port and marine sector. Complementary to the available information published by the different governmental institutions, this report includes insights of several stakeholders from the Mexican government and local port authorities. Altogether, the information provided in this report is the product of information gathered from Mexican public institutions combined with information provided by key companies that possess expert knowledge regarding sustainable port development. Firstly, a schematic overview of the institutional port framework will be laid out in order to have a basic understanding of the institutions that have the authority over ports in Mexico and how they are regulated. The agencies in charge of ports will be the primary line of contact for companies who are interested in the development opportunities that will most likely crop up in 2019 and beyond. -

Coatzacoalcos, Veracruz

COATZACOALCOS, VERACRUZ I. DATOS GENERALES DEL PUERTO. 1. Nombre del Puerto: Coatzacoalcos.-Anteriormente llamado Puerto México, es un puerto comercial e industrial que, aunado al recinto portuario de Pajaritos, conforma un conjunto de instalaciones portuarias de gran capacidad para el manejo de embarcaciones de gran tamaño y altos volúmenes de carga. Se localiza sobre la margen W del Río Coatzacoalcos. El Puerto de Coatzacoalcos, sede de la cabecera municipal del mismo nombre, es considerado como el polo de desarrollo más importante en el sur de Veracruz, debido a su ubicación estratégica que le ha permitido ser un centro de distribución de distintas mercancías así como por considerarse uno de los puertos más importantes en la producción petroquímica y petrolera del país. El corredor industrial formado entre Coatzacoalcos y Minatitlán comprende una zona de influencia que abarca las ciudades de Cosoleacaque, Nanchital, Agua Dulce y Las Choapas, extendiendo su área de influencia hasta la ciudad de Acayúcan, Veracruz y La Venta, Tabasco. 2. Ubicación y Límites geográficos del puerto. El Puerto de Coatzacoalcos, ubicado al norte del Istmo de Tehuantepec, limita con los municipios de: Chinameca, Moloacán, Oteapan, Minatitlán, Las Choapas, Agua Dulce, Nanchital, e Ixhuatlán del Sureste; y alberga a los Ejidos de: 5 de Mayo, Francisco Villa, La Esperanza, Lázaro Cárdenas, Manuel Almanza, Paso a Desnivel y Rincón Grande; la Villa de Allende, las congregaciones de: Colorado, Guillermo Prieto, Las Barrillas y Mundo Nuevo y a la Cabecera Municipal: La Ciudad de Coatzacoalcos. El puerto está vinculado con el puerto de Salina Cruz, con el que tiene una distancia de 300 Km., Coatzacoalcos ofrece la oportunidad de operar un corredor de transporte intermodal para tráfico internacional de mercancías y constituye la base para el desarrollo de actividades industriales, agropecuarias, forestales y comerciales en la región del Istmo de Tehuantepec. -

El Contenido De Este Archivo No Podrá Ser Alterado O Modificado Total O Parcialmente, Toda Vez Que Puede Constituir El Delito D

EL CONTENIDO DE ESTE ARCHIVO NO PODRÁ SER ALTERADO O MODIFICADO TOTAL O PARCIALMENTE, TODA VEZ QUE PUEDE CONSTITUIR EL DELITO DE FALSIFICACIÓN DE DOCUMENTOS DE CONFORMIDAD CON EL ARTÍCULO 244, FRACCIÓN III DEL CÓDIGO PENAL FEDERAL, QUE PUEDE DAR LUGAR A UNA SANCIÓN DE PENA PRIVATIVA DE LA LIBERTAD DE SEIS MESES A CINCO AÑOS Y DE CIENTO OCHENTA A TRESCIENTOS SESENTA DÍAS MULTA. DIRECION GENERAL DE IMPACTO Y RIESGO AMBIENTAL MANIFESTACIÓN DE IMPACTO AMBIENTAL MODALIDAD PARTICULAR PARA LA “LIMPIEZA, DESAZOLVE Y OBRAS DE RECONSTRUCCIÓN DEL CAUCE NATURAL DEL ARROYO TEAPA, A LA ALTURA DE LA LOCALIDAD DE LA Proyectos Ambientales CANGREJERA, MUNICIPIO DE COATZACOALCOS, VER." Gatica S.A de C.V MANIFESTACIÓN DE IMPACTO AMBIENTAL MODALIDAD PARTICULAR “LIMPIEZA, DESAZOLVE Y OBRAS DE RECONSTRUCCIÓN DEL CAUCE NATURAL DEL ARROYO TEAPA, A LA ALTURA DE LA LOCALIDAD DE LA CANGREJERA, MUNICIPIO DE COATZACOALCOS, VER." SECTOR: HIDRÁULICO 1 PROMOVENTE: ORGANISMO DE CUENCA GOLFO CENTRO DE CONAGUA DIRECCIÒN COL. 16 DE SEPTIEMBRE MZA5 LY13 COL MOVIMIENTO TERRITORIAL 39079.CHILPANCINGO DE LOS BRAVO. GUERRERO. CORREO ELECTRÓNICO: [email protected],[email protected] CELULAR: 7475452140 / OFICINA: 7471393121 MANIFESTACIÓN DE IMPACTO AMBIENTAL MODALIDAD PARTICULAR PARA LA “LIMPIEZA, DESAZOLVE Y OBRAS DE RECONSTRUCCIÓN DEL CAUCE NATURAL DEL ARROYO TEAPA, A LA ALTURA DE LA LOCALIDAD DE LA Proyectos Ambientales CANGREJERA, MUNICIPIO DE COATZACOALCOS, VER." Gatica S.A de C.V CONTENIDO GENERAL Pág. CAPITULO. - I DATOS GENERALES DEL PROYECTO DEL PROMOVENTE Y DEL RESPONSABLE DEL ESTUDIO DE 12 IMPACTO AMBIENTAL I.1 Datos generales del Proyecto 12 I.1.1 Nombre del proyecto 12 I.1.2 Ubicación del proyecto 12 I.1.3 Tiempo de vida útil del proyecto 18 I.2. -

Home Range Dynamics of the Tehuantepec Jackrabbit in Oaxaca, Mexico

Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 81: 143- 151, 2010 Home range dynamics of the Tehuantepec Jackrabbit in Oaxaca, Mexico Dinámica del ámbito hogareño de la liebre de Tehuantepec en Oaxaca, México Arturo Carrillo-Reyes1*, Consuelo Lorenzo1, Eduardo J. Naranjo1, Marisela Pando2 and Tamara Rioja3 1El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, Conservación de la Biodiversidad, Departamento de Ecología y Sistemática Terrestres. Carretera Panamericana y Periférico Sur s/n. 29290, San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas, México. 2Facultad de Ciencias Forestales, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León. Carretera Panamericana km 145 s/n. 87700 Linares, Nuevo León, México. 3Oikos: Conservación y Desarrollo Sustentable A.C. Sol 22, Bismark. 29267, San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas, México. *Correspondent: [email protected] Abstract. Information on the spatial ecology of the Tehuantepec jackrabbit (Lepus fl avigularis) is important for developing management strategies to preserve it in its habitat. We radio-collared and monitored 60 jackrabbits from May 2006 to April 2008. We estimated annual and seasonal home ranges and core areas by using the fi xed-kernel isopleth to 95% and 50% of confi dence, respectively. This jackrabbit showed a highly variable seasonal home range: 1.13 ha to 152.61 ha for females and 0.20 ha to 71.87 ha for males. Annual and seasonal home ranges and core areas of females were signifi cantly wider than male home ranges. There was considerable overlap of ranges within and between sexes, with the home range of each jackrabbit overlapping with the ranges of 1 to 46 other individuals. Home range and overlap analysis confi rms that the Tehuantepec jackrabbit is a polygamous and non-territorial species. -

Listado De Canales Virtuales

LISTADO CANALES VIRTUALES Nacionales 1 Canal Virtual 1 (Azteca Trece) No. POBLACIÓN ESTADO CONCESIONARIO / PERMISIONARIO DISTINTIVO CANAL VIRTUAL 1 AGUASCALIENTES AGUASCALIENTES XHJCM-TDT 1.1 2 ENSENADA XHENE-TDT 1.1 BAJA CALIFORNIA 3 SAN FELIPE XHFEC-TDT 1.1 4 CD. CONSTITUCIÓN XHCOC-TDT 1.1 5 LA PAZ BAJA CALIFORNIA SUR XHAPB-TDT 1.1 6 SAN JOSÉ DEL CABO XHJCC-TDT 1.1 7 CAMPECHE XHGE-TDT 1.1 8 CD. DEL CARMEN CAMPECHE XHGN-TDT 1.1 9 ESCÁRCEGA XHPEH-TDT 1.1 10 ARRIAGA XHOMC-TDT 1.1 11 COMITÁN DE DOMÍNGUEZ XHDZ-TDT 1.1 CHIAPAS 12 SAN CRISTÓBAL DE LAS CASAS XHAO-TDT 1.1 13 TAPACHULA XHTAP-TDT 1.1 14 CD. JIMÉNEZ XHJCH-TDT 1.1 15 CHIHUAHUA XHCH-TDT 1.1 16 CHIHUAHUA XHIT-TDT 1.1 CHIHUAHUA 17 HIDALGO DEL PARRAL XHHPC-TDT 1.1 18 NUEVO CASAS GRANDES XHCGC-TDT 1.1 19 OJINAGA XHHR-TDT 1.1 20 MÉXICO CIUDAD DE MÉXICO XHDF-TDT 1.1 21 CD. ACUÑA XHHE-TDT 1.1 22 MONCLOVA XHHC-TDT 1.1 23 PARRAS DE LA FUENTE COAHUILA XHPFC-TDT 1.1 24 SABINAS XHCJ-TDT 1.1 25 TORREÓN XHGDP-TDT 1.1 26 COLIMA XHKF-TDT 1.1 27 MANZANILLO COLIMA XHDR-TDT 1.1 28 TECOMÁN XHTCA-TDT 1.1 29 CUENCAMÉ XHVEL-TDT 1.1 30 DURANGO XHDB-TDT 1.1 DURANGO 31 GUADALUPE VICTORIA XHGVH-TDT 1.1 32 SANTIAGO PAPASQUIARO TELEVISIÓN AZTECA, S.A. DE C.V. XHPAP-TDT 1.1 33 CELAYA GUANAJUATO XHMAS-TDT 1.1 34 ACAPULCO XHIE-TDT 1.1 35 CHILPANCINGO XHCER-TDT 1.1 36 IGUALA GUERRERO XHIR-TDT 1.1 37 TAXCO DE ALARCÓN XHIB-TDT 1.1 38 ZIHUATANEJO XHDU-TDT 1.1 39 TULANCINGO HIDALGO XHTGN-TDT 1.1 40 GUADALAJARA XHJAL-TDT 1.1 JALISCO 41 PUERTO VALLARTA XHGJ-TDT 1.1 42 JOCOTITLÁN MÉXICO XHXEM-TDT 1.1 43 LÁZARO CÁRDENAS -

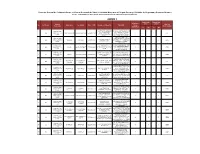

Nombre Apellido Paterno Apellido Materno Carrera Región Modalidad Examen CENEVAL Examen De Habilidades Musicales Lugar MARTIN Y

Nombre Apellido Paterno Apellido Materno Carrera Región Modalidad Examen CENEVAL Examen de Habilidades Musicales Lugar MARTIN YASUO GUERRERO KOJIMA EDUCACION MUSICAL XALAPA ESCOLARIZADO XALAPA 28/mayo/2015, 08:00 hrs. Auditorio CARLOS GERMAÍN SANTOS ABURTO EDUCACION MUSICAL XALAPA ESCOLARIZADO XALAPA 28/mayo/2015, 08:00 hrs. Auditorio IVAN MARTIN WONG GARCIA EDUCACION MUSICAL XALAPA ESCOLARIZADO XALAPA 28/mayo/2015, 08:00 hrs. Auditorio JENNYFER POLET SANTIAGO GRAJALES EDUCACION MUSICAL XALAPA ESCOLARIZADO XALAPA 28/mayo/2015, 08:00 hrs. Auditorio ANDREA CAMPOS HUERTA EDUCACION MUSICAL XALAPA ESCOLARIZADO XALAPA 28/mayo/2015, 08:00 hrs. Auditorio MAGNOLIA SONDEREGGER CASTILLO EDUCACION MUSICAL XALAPA ESCOLARIZADO XALAPA 28/mayo/2015, 08:00 hrs. Auditorio MARÍA FERNANDA PÉREZ DAVID EDUCACION MUSICAL XALAPA ESCOLARIZADO XALAPA 28/mayo/2015, 08:00 hrs. Auditorio ISMAEL RODRIGUEZ HERNANDEZ EDUCACION MUSICAL XALAPA ESCOLARIZADO XALAPA 28/mayo/2015, 08:00 hrs. Auditorio MARTHA FRANCISCA VARGAS DIAZ EDUCACION MUSICAL XALAPA ESCOLARIZADO XALAPA 28/mayo/2015, 08:00 hrs. Auditorio ZABDAI OLIVO ACUÑA EDUCACION MUSICAL XALAPA ESCOLARIZADO XALAPA 28/mayo/2015, 08:00 hrs. Auditorio FRANCISCO GERARDO JARAMILLO CORTÉS EDUCACION MUSICAL XALAPA ESCOLARIZADO XALAPA 28/mayo/2015, 08:00 hrs. Auditorio JAIR PIMENTEL LOPEZ EDUCACION MUSICAL XALAPA ESCOLARIZADO XALAPA 28/mayo/2015, 08:00 hrs. Auditorio BENILDE MARIA LARIOS CANSECO EDUCACION MUSICAL XALAPA ESCOLARIZADO XALAPA 28/mayo/2015, 08:00 hrs. Auditorio MARIANA HERNANDEZ RIVERA EDUCACION MUSICAL XALAPA ESCOLARIZADO XALAPA 28/mayo/2015, 08:00 hrs. Auditorio JHOVANY JUAN HERNANDEZ EDUCACION MUSICAL XALAPA ESCOLARIZADO XALAPA 28/mayo/2015, 08:00 hrs. Auditorio MARCO POLO HERNANDEZ LANDA EDUCACION MUSICAL XALAPA ESCOLARIZADO XALAPA 28/mayo/2015, 08:00 hrs. -

Trichechus Manatus Manatus) in the South of Veracruz, Mexico

Use and Characterizaon of Habitat by the An/llean Manatee (Trichechus manatus manatus) in the South of Veracruz, Mexico. Ibiza Mar@nez-Serrano1, Denise Lubinsky-Jinich2, Naylú A. Morales-García1, Emilio A. Suárez-Domínguez1Blanca E. Cor/na-Julio3 1 Facultad de Biología, Universidad Veracruzana. Circ. Gonzálo Aguirre Beltrán s/n Xalapa,Veracruz, México. [email protected]; [email protected] ; [email protected] 2 Centro de InvesEgación CienOfica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada. Ensenada, BC, México. [email protected] 3 InsEtuto de InvesEgaciones Biológicas, Universidad Veracruzana. Av. Luis Castelazo s/n Xalapa, Veracruz, México. OBJECTIVES In México, the Antillean Manatee lives at - To assess systemacally the manatee presence coastal lagoons, estuaries and rivers from at ALS Veracruz, Tabasco, Chiapas, and Quintana - To know the distribuEon inside the ALS Roo states. Their main threats are illegal - To determine habitat preferences hunting, pollution and habitat loss. METHODS In Veracruz, the northern boundary of its distribution had been reported for the Alvarado Lagoon System (ALS) (Rodas-Trejo, 2008; Daniel-Renteria et al., 2012) and Four regions, three seasons population trends remain unknown. Indirect sightings: interviews with local people However, there are anecdotic reports about its presence at the south of Veracruz in the Coatzacoalcos river. 234 navigation hours RESULTS 1,200 km surveyed Main activities: Social, breeding, play, traveling Depth Temperature Salinity Conductivity Dissolved oxigen Turbidity FURTHERMORE… TO DO: - All the habitat characterizaon - To take physical and chemical parameters in Coatzacoalcos - To conduct behavioral studies - To esEmate abundance and other populaon parameters - Social and economical studies around manatee conservaon REFERENCES 1. Daniel-Rentería, I.C., A. -

Movilidad Y Desarrollo Regional En Oaxaca

ISSN 0188-7297 Certificado en ISO 9001:2000‡ “IMT, 20 años generando conocimientos y tecnologías para el desarrollo del transporte en México” MOVILIDAD Y DESARROLLO REGIONAL EN OAXACA VOL1: REGIONALIZACIÓN Y ENCUESTA DE ORIGÉN Y DESTINO Salvador Hernández García Martha Lelis Zaragoza Manuel Alonso Gutiérrez Víctor Manuel Islas Rivera Guillermo Torres Vargas Publicación Técnica No 305 Sanfandila, Qro 2006 SECRETARIA DE COMUNICACIONES Y TRANSPORTES INSTITUTO MEXICANO DEL TRANSPORTE Movilidad y desarrollo regional en oaxaca. Vol 1: Regionalización y encuesta de origén y destino Publicación Técnica No 305 Sanfandila, Qro 2006 Esta investigación fue realizada en el Instituto Mexicano del Transporte por Salvador Hernández García, Víctor M. Islas Rivera y Guillermo Torres Vargas de la Coordinación de Economía de los Transportes y Desarrollo Regional, así como por Martha Lelis Zaragoza de la Coordinación de Ingeniería Estructural, Formación Posprofesional y Telemática. El trabajo de campo y su correspondiente informe fue conducido por el Ing. Manuel Alonso Gutiérrez del CIIDIR-IPN de Oaxaca. Índice Resumen III Abstract V Resumen ejecutivo VII 1 Introducción 1 2 Situación actual de Oaxaca 5 2.1 Situación socioeconómica 5 2.1.1 Localización geográfica 5 2.1.2 Organización política 6 2.1.3 Evolución económica y nivel de desarrollo 7 2.1.4 Distribución demográfica y pobreza en Oaxaca 15 2.2 Situación del transporte en Oaxaca 17 2.2.1 Infraestructura carretera 17 2.2.2 Ferrocarriles 21 2.2.3 Puertos 22 2.2.4 Aeropuertos 22 3 Regionalización del estado -

Administración Portuaria Integral De Salina Cruz, S.A. De C.V

CUENTA PÚBLICA 2018 ADMINISTRACIÓN PORTUARIA INTEGRAL DE SALINA CRUZ, S.A. DE C.V. INTRODUCCIÓN 1. RESEÑA HISTÓRICA Con una historia que data de principios del siglo pasado, el puerto de Salina Cruz, ha experimentado etapas muy diversas e incluso contrastantes, que se explican fundamentalmente por su ubicación en el extremo occidental nacional, en la franja más angosta del territorio mexicano. Esta característica le ha significado el tomar parte en varios proyectos de gran alcance que se han enfocado en la posibilidad de crear un puente terrestre para canalizar los vigorosos tráficos comerciales interoceánicos a través del llamado “Corredor Transístmico” o del Istmo de Tehuantepec. Durante el porfiriato, en la primera década del siglo pasado, se finalizaron las obras portuarias en ambos extremos del corredor y se inició el proceso de urbanización de Salina Cruz. Sin lugar a duda el principal “rol” que a la fecha ha llegado a desempeñar el Puerto de Salina Cruz en el Sistema Portuario Nacional por su aporte a la actividad económica tiene que ver con su función de distribuidor de petrolíferos en el pacífico. En esta función el puerto se vincula con Puertos como Guaymas, Mazatlán, Lázaro Cárdenas, entre otros puntos que fungen como receptores en el litoral conformando una red o sistema de distribución tierra adentro de combustibles y/o petrolíferos. El puerto de Salina Cruz, Oaxaca, se caracteriza por manejar el tráfico de carga de la región sur y sureste de la República Mexicana que comprende los estados de Oaxaca, Chiapas, Veracruz, Campeche, Tabasco, Puebla, entre otros. Los principales productos que se manejan en esta región son: café, productos químicos, cemento, cerveza, madera, azúcar; asimismo, fertilizante de importación y maíz de cabotaje, los cuales son distribuidos a las zonas de consumo agrícola. -

Región Coatzacoalcos-Minatitlán

Región Coatzacoalcos-Minatitlán “Lis de Veracruz: Arte, Ciencia, Luz” Universidad Veracruzana 2º Informe de Actividades 2018-2019 Pertenencia y Pertinencia Región Coatzacoalcos-Minatitlán Universidad Veracruzana Universidad Veracruzana Mtro. Carlos Lamothe Zavaleta Vicerrector de la región Coatzacoalcos-Minatitlán Lic. Florentino Cruz Martínez Secretario Académico Regional Lic. María Inés Quevedo López Secretaria de Administración y Finanzas Regional Mtro. Manuel Alejandro López Sibaja Coordinador Regional de Desarrollo Institucional 2 2º Informe de Actividades 2018-2019 Región | Región Coatzacoalcos-Minatitlán Universidad Veracruzana Contenido Mensaje del Vicerrector 5 Introducción 7 I. Liderazgo académico 15 1. Oferta educativa de calidad 17 2. Planta académica 25 3. Apoyo al estudiante 30 4. Investigación, innovación y desarrollo tecnológico 33 I. Visibilidad e impacto social 35 5. Vinculación y responsabilidad social universitaria 37 6. Emprendimiento y egresados 44 7. Cultura humanista y desarrollo sustentable 46 8. Internacionalización e interculturalidad 49 III. Gestión y gobierno 52 9. Gobernanza universitaria 54 10. Financiamiento 61 11. Infraestructura física y tecnológica 66 Siglario 71 3 2º Informe de Actividades 2018-2019 | Región Coatzacoalcos-Minatitlán Universidad Veracruzana 4 2º Informe de Actividades 2018-2019 Región | Región Coatzacoalcos-Minatitlán Universidad Veracruzana Mensaje del Vicerrector ace dos años que la Rectora de la Universidad Veracruzana, Dra. Sara H Ladrón de Guevara González, en ejercicio de la atribución que le otorga el artículo 38, fracción VIII, y 57 de la Ley Orgánica vigente, me desig- nó vicerrector de la región Coatzacoalcos-Minatitlán. A esa alta distinción he correspondido con responsabilidad, servicio y compromiso institucional, para conducir a un puerto seguro a la región uni- versitaria que me ha sido confiada. -

VERACRUZ.Pdf

Convenio General de Colaboración que celebra la Secretaría de Salud, el Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social y el Instituto de Seguridad y Servicios Sociales de los Trabajadores del Estado para la Atención de Emergencias Obstétricas. ANEXO 1 Cuenta con Cuenta con Número de Entidad UCI* UCIN** Nivel de No. Institución Municipio Localidad Clave: CLUES Nombre del Hospital Domicilio Camas Federativa Resolutividad Obstétricas Si No Si No HOSPITAL REGIONAL DE AV. IGNACIO ZARAGOZA No. 801 VERACRUZ DE COATZACOALCOS COL. CENTRO, C.P. 96400, 1 SS IGNACIO DE LA COATZACOALCOS COATZACOALCOS VZSSA001150 25 X X ALTA DR.VALENTIN GÓMEZ MPIO. COATZACOALCOS, LLAVE FARIAS COATZACOALCOS, VERACRUZ. KM. 341.5 CARRETERA VERACRUZ DE CORDOBA-VERACRUZ, ZONA HOSPITAL GENERAL 2 SS IGNACIO DE LA CÓRDOBA CÓRDOBA VZSSA001355 INDUSTRIAL,C.P. 94690, MPIO. 20 X X MEDIA CORDOBA YANGA LLAVE CORDOBA, CORDOBA, VERACRUZ AV. RUIZ CORTINEZ NO. 2903, VERACRUZ DE CENTRO DE ALTA COL. UNIDAD MAGISTERIAL, 3 SS IGNACIO DE LA XALAPA XALAPA-ENRÍQUEZ VZSSA002965 ESPECIALIDAD DR. RAFAEL 27 X X MEDIA C.P. 91020, MPIO. XALAPA, LLAVE LUCIO XALAPA, VERACRUZ VERACRUZ DE HOSPITAL REGIONAL DE CALLE PEDRO RENDON NO. 1 , 4 SS IGNACIO DE LA XALAPA XALAPA-ENRÍQUEZ VZSSA002970 XALAPA DR. LUIS F. COL. CENTRO, CP.91000, MPIO. 27 X X MEDIA LLAVE NACHON XALAPA, XALAPA, VERACRUZ CALLE DE LAS FLORES S/N VERACRUZ DE POZA RICA DE POZA RICA DE HOSPITAL REGIONAL POZA ESQ. PIPILA COL. LAS VEGAS, 5 SS IGNACIO DE LA VZSSA004744 18 X X ALTA HIDALGO HIDALGO RICA DE HIDALGO C.P. 93210, MPIO. POZA RICA, LLAVE POZA RICA, VERACRUZ. ENTRONQUE AUTOPISTA ORIZABA-PUEBLA KM.2, C.P.