Illinois Classical Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Autechre Confield Mp3, Flac, Wma

Autechre Confield mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Confield Country: UK Released: 2001 Style: Abstract, IDM, Experimental MP3 version RAR size: 1635 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1586 mb WMA version RAR size: 1308 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 182 Other Formats: AU DXD AC3 MPC MP4 TTA MMF Tracklist 1 VI Scose Poise 6:56 2 Cfern 6:41 3 Pen Expers 7:08 4 Sim Gishel 7:14 5 Parhelic Triangle 6:03 6 Bine 4:41 7 Eidetic Casein 6:12 8 Uviol 8:35 9 Lentic Catachresis 8:30 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Warp Records Limited Copyright (c) – Warp Records Limited Published By – Warp Music Published By – Electric And Musical Industries Made By – Universal M & L, UK Credits Mastered By – Frank Arkwright Producer [AE Production] – Brown*, Booth* Notes Published by Warp Music Electric and Musical Industries p and c 2001 Warp Records Limited Made In England Packaging: White tray jewel case with four page booklet. As with some other Autechre releases on Warp, this album was assigned a catalogue number that was significantly ahead of the normal sequence (i.e. WARPCD127 and WARPCD129 weren't released until February and March 2005 respectively). Some copies came with miniature postcards with a sheet a stickers on the front that say 'autechre' in the Confield font. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode (Sticker): 5 021603 128125 Barcode (Printed): 5021603128125 Matrix / Runout (Variant 1 to 3): WARPCD128 03 5 Matrix / Runout (Variant 1 to 3, Etched In Inner Plastic Hub): MADE IN THE UK BY UNIVERSAL M&L Mastering SID Code -

Filmar Habis 47 Color.Indd

http://dx.doi.org/10.12795/Habis.2016.i47.04 SOBRE EL PROBLEMA DE LA PAROXITONESIS Alejandro Abritta Universidad de Buenos Aires – Conicet [email protected] ON THE PROBLEM OF PAROXYTONESIS RESUMEN: El presente artículo propone una ABSTRACT: The following paper presents a re- reconsideración del fenómeno de la paroxitone- view of the phenomenon of paroxytonesis in the sis en el trímetro yámbico y el coliambo a partir iambic trimeter and the choriamb starting from a de una modificación de dos supuestos metodo- modification of two methodological assumptions lógicos (la interpretación del principio breuis in (the interpretation of the principle brevis in longo longo y la teoría del acento) del análisis del fe- and the theory of Ancient Greek accent) of Hans- nómeno de Hanssen (1883), que es todavía hoy la sen’s (1883) analysis of the phenomenon, which is principal fuente de datos sobre el tema, en par- still the main source of data on the subject, particu- ticular en el caso del trímetro. Tras una intro- larly in the case of the trimeter. After an introduc- ducción al problema y una serie de aclaraciones tion to the problem and a number of methodological metodológicas, el autor estudia en orden los dos clarifications, the author studies in order both types tipos de metro para concluir que las tesis de Hans- of meter in order to conclude that Hanssen’s theses sen admiten correcciones considerables. allow for considerable corrections. PALABRAS CLAVE: Trímetro yámbico, Co- KEYWORDS: Iambic trimeter, Choriamb, Paro- liambo, Paroxitonesis, breuis in longo. xytonesis, breuis in longo. RECIBIDO: 03.10.2015. -

Epitoma De Tito Liuio Digiliblt

Florus Epitoma de Tito Liuio digilibLT. Biblioteca digitale di testi latini tardoantichi. Progetto diretto da Raffaella Tabacco (responsabile della ricerca) e Maurizio Lana Florus Epitoma de Tito Liuio Correzione linguistica : Manuela Naso Codifica XML : Nadia Rosso 2011 DigilibLT, Vercelli Fonte Florus, Oeuvres, tome I et tome II, texte établi et traduit par Paul Jal, Paris 1967 (Collection des Universités de France) Licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione - Non commerciale - Condividi allo stesso modo 3.0 Italia Nota al testo Note di trascrizione e codifica del progetto digilibLT Abbiamo riportato solo il testo stabilito dall'edizione di riferimento non seguendone l'impaginazione. Sono stati invece esclusi dalla digitalizzazione apparati, introduzioni, note e commenti e ogni altro contenuto redatto da editori moderni. I testi sono stati sottoposti a doppia rilettura integrale per garantire la massima correttezza di trascrizione Abbiamo normalizzato le U maiuscole in V seguendo invece l'edizione di riferimento per la distinzione u/v minuscole. Non è stato normalizzato l'uso delle virgolette e dei trattini. Non è stata normalizzata la formattazione nell'intero corpus: grassetto, corsivo, spaziatura espansa. Sono stati normalizzati e marcati nel modo seguente i diacritici. espunzioni: <del>testo</del> si visualizza [testo] integrazioni: <supplied>testo</supplied> si visualizza <testo> loci desperationis: <unclear>testo</unclear> o <unclear/> testo si visualizzano †testo† e †testo lacuna materiale: <gap/> si visualizza [...] lacuna integrata -

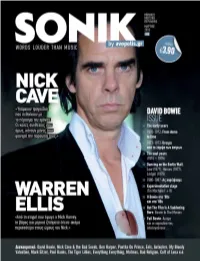

Sonik84full.Pdf

ww Depeche Mode by D.A. Pennebaker Chris Hegedus 101The Movie David Dawkins ΑΘΗΝΑ Προπώληση εισιτηρίων από 01.03.13 στα ταμεία του θεάτρου Badminton ΔΕΥΤΕΡΑ 01.04.13 Ολυμπιακά Ακίνητα Γουδή. Tηλ: 13855 & 210.88.40.600 Photo: Anton Corbijn. Design: Dimitris Panagiotakopoulos Kινηματογράφος ΘΕΣΣΑΛΟΝΙΚΗ Ολύμπιον Προπώληση εισιτηρίων από 01.03.13 στα ταμεία του Kινηματογράφου Ολύμπιον ΣΑΒΒΑΤΟ 06.04.13 Πλατεία Αριστοτέλους 10. Τηλ: 2310 378400 ΧΟΡΗΓΟΣ Μοναδικός. Καθημερινός. Αληθινός sonik_dm_21x27.5.indd 1 27/02/2013 3:32 μ.μ. 4 | LOGΙΝ Μηνιαίο μουσικό περιοδικό Mάρtιος 2013 ISSN: 1790-1960 Περιεχόμενα 6 My Latest Obsession 10 αναγνώστες του SONIK μας γνωστοποιούν το τελευταίο τους κόλλημα 10 SONIK World Τάσεις, εξελίξεις και προτάσεις από την παγκόσμια μουσική σφαίρα EDITORIAL 14 SONIK Greek Τάσεις, εξελίξεις και προτάσεις από την ελληνική μουσική σκηνή Τις μέρες που κλείνουμε το παρόν τεύχος, το YouTube έχει γεμίσει και αγορά σχόλια επιδοκιμασιών (αλλά και –αναμενόμενα– ειρωνειών) για το spoken word single/video “Lightning Bolts” του Nick Cave. Πέρα 18 Nick Cave «Υπάρχουν τραγούδια που πεθαίνουν με το πέρασμα του χρόνου. από τις υπερβολές περί αρχαίας τραγωδίας, μεταφορών περί κε- Οι καλές συνθέσεις σου, όμως, κάνουν μόνες τους φανερή ραυνών του Δία κ.α., ένας στίχος πρέπει να ανησυχήσει τη δική μας, την παρουσία τους.» εγχώρια μουσική ελίτ που απαξιεί να ασχοληθεί σοβαρά με το 22 Warren Ellis θέμα: «Στην Αθήνα οι νέοι κλαίνε από τα δακρυγόνα – εγώ είμαι «Από τη στιγμή που έφυγε ο Mick Harvey, το βάρος για μερικά στην πισίνα του ξενοδοχείου μου μαυρίζοντας». Δεν ξέρω αν χρει- ζητήματα έπεσε ακόμα περισσότερο στους ώμους του Nick.» αζόμαστε συμπόνια, αν οι εικόνες αυτές δεν βοηθούν τον τουρι- 28 The ch-ch-changing face of David Bowie σμό, αν απλώς είναι λαϊκίστικες κορώνες, αν απευθύνονται καν σε μας. -

Jordanes and the Invention of Roman-Gothic History Dissertation

Empire of Hope and Tragedy: Jordanes and the Invention of Roman-Gothic History Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Brian Swain Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Timothy Gregory, Co-advisor Anthony Kaldellis Kristina Sessa, Co-advisor Copyright by Brian Swain 2014 Abstract This dissertation explores the intersection of political and ethnic conflict during the emperor Justinian’s wars of reconquest through the figure and texts of Jordanes, the earliest barbarian voice to survive antiquity. Jordanes was ethnically Gothic - and yet he also claimed a Roman identity. Writing from Constantinople in 551, he penned two Latin histories on the Gothic and Roman pasts respectively. Crucially, Jordanes wrote while Goths and Romans clashed in the imperial war to reclaim the Italian homeland that had been under Gothic rule since 493. That a Roman Goth wrote about Goths while Rome was at war with Goths is significant and has no analogue in the ancient record. I argue that it was precisely this conflict which prompted Jordanes’ historical inquiry. Jordanes, though, has long been considered a mere copyist, and seldom treated as an historian with ideas of his own. And the few scholars who have treated Jordanes as an original author have dampened the significance of his Gothicness by arguing that barbarian ethnicities were evanescent and subsumed by the gravity of a Roman political identity. They hold that Jordanes was simply a Roman who can tell us only about Roman things, and supported the Roman emperor in his war against the Goths. -

El Debate 19291119

El, TIEMPO (Servicio Meteorológico Oficial) .—Probable para la mañana de hoy: Cantabria y Galicia, algunas PRECIOS DE SUSCRIPCIÓN lluvias. Resto de España, buen tiempo, poco estable. Temperatura máxima del domingo: 20 en Almería y 2,00 peaeUs |d mea Huelva; mínima, 1 bajo cero en Falencia y Segovla. PROVINCIAS 9,00 ptaa. txlmati* En Madrid: máxima de ayer, 11,6; mínima, 3,6. (Véase en séptima plana el Boletín Meteorológico.) PAGO ADEXANTADO FRANQCKO CONCERTADO MADRID.—Año XIX.—Núm. 6.848 Martes 19 de noviembre de 1929 CINCO EDICIONES DIARIAS Apartado 468,—Red. y AdmAn,. COLEGIATA, 7. Teléfonos 71500. 71501. 71509 y 72805. EL PÜT^IINIO ARTÍSTICO E HISTÓRICO EN MÉJICO KAnDO LO DEL DÍAERANCI A QUIERE APLAZAR EL PÜBTIDO NIICIONIILISTII Grandioso homenaje 1.a censura al Pontífíce No ocviUamoK el asombro que nos ha producido la nota que nos envía para LA II CONFERENCIA DE DEimOTIIDO EN PRUSIII su publicación el señor duque de Berwick y de Alba como director de la Aca Píscym oBTiz RUBIO En sus última—s declaracione s ha ex EL DOMINGO POR LA NOCHE puesto él presidente dd Consejo algunos HA PERDIDO PUESTOS EN TODOS demia de la Historia. Ya la propia corporación sospecha que hay motivos para de sus puntos de vista para el día en que LAS REPARACIONES CUATRO VOTOS DEL NUNCIO DE asombrarse cuando en el mismo documento quiere prevenirse afirmando que TENIA 1.350.000 VOTOS SU SANTIDAD SOBRE LA desaparezca la censura. Desde lu«go ni • LOS AYUNTAMIENTOS no la g^ía "partidismo" algfuno. el marqués de Estella ni nadie puede • ACCIÓN CATÓLICA Pero el documento que se nos envía parece partidista, por más Objetiva Ha habido choques sangrientos concebir a la ceinsura como institución Propone que no se reúna en La Sus electores han votado por frialdad que se ponga en su examen. -

The Idea of the Labyrinth

·THE IDEA OF · THE LABYRINTH · THE IDEA OF · THE LABYRINTH from Classical Antiquity through the Middle Ages Penelope Reed Doob CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS ITHACA AND LONDON Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Copyright © 1990 by Cornell University First printing, Cornell Paperbacks, 1992 Second paperback printing 2019 All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. Visit our website at cornellpress.cornell.edu. Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-8014-2393-2 (cloth: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-5017-3845-6 (pbk.: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-5017-3846-3 (pdf) ISBN 978-1-5017-3847-0 (epub/mobi) Librarians: A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress An open access (OA) ebook edition of this title is available under the following Creative Commons license: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0): https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by- nc-nd/4.0/. For more information about Cornell University Press’s OA program or to download our OA titles, visit cornellopen.org. Jacket illustration: Photograph courtesy of the Soprintendenza Archeologica, Milan. For GrahamEric Parker worthy companion in multiplicitous mazes and in memory of JudsonBoyce Allen and Constantin Patsalas Contents List of Plates lX Acknowledgments: Four Labyrinths xi Abbreviations XVll Introduction: Charting the Maze 1 The Cretan Labyrinth Myth 11 PART ONE THE LABYRINTH IN THE CLASSICAL AND EARLY CHRISTIAN PERIODS 1. -

2004 Law and Medical Ethics in A

G 20438 50 OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE WORLD MEDICAL ASSOCIATION VOL. 50 NO 1, March 2004 Editorial – The World Medical Journal 1954 – 2004 – yesterday, today and tomorrow . 1 A Rational Approach To Drug Design . 2 Medical Ethics and Human Rights – Medicine, the Law and Medical Ethics in a Changing Society . 5 Helsinki and the Declaration of Helsinki . 9 Linking moral progress to medical progress: New opportunities for the Declaration of Helsinki . 11 WMA – "Getting it Right for our Children" . 13 Medical Science, Professional Practice and Education – Orthopaedic Surgeons Are Failing To Prevent Osteoporotic Fractures . 17 Relationship Based Health Care in Six Countries . 18 WHO – More Research, More Resources Needed To Control Expanding Global Diseases . 19 Health And Finance Ministers Address Need For World-wide Increase In Health Investment . 20 WHO welcomes new initiative to cut the price of Aids medicines . 20 Maternal Deaths Disproportionately High In Developing Countries. 21 Photo: Prof. Dr. Dr. M. Putscher Dr. Photo: Prof. Dr. HIPPOKRATES WMA – Secretary General: From the Secretary General's Desk . 22 World Medical Journal 1954 – 2004 Regional and NMA News – Social Security is a National Security Issue . 23 Health Reform in Germany Law and Medical Ethics in a "sustaining or diluting social insurance?" . 24 The South African Medical changing society Association's work on the HIV/Aids front . 25 Norwegian Medical Association . 27 U.K.: New report details the impact of smoking “Getting it right for our children” on sexual, reproductive and child health . 27 Fiji and India . 28 News from the Regions Book Review . 28 WMA OFFICERS OF NATIONAL MEMBER MEDICAL ASSOCIATIONS AND OFFICERS Vice-President President Immediate Past-President Dr. -

Virgil's Pier Group

Virgil’s Pier Group In this paper I argue that the ship race of Aeneid 5 presents a metapoetic commentary whereby Virgil re-validates heroic epic and announces the principal intertexts of his middle triad. The games as a whole are rooted in transparent allusion to Iliad 23 and have, accordingly, drawn somewhat less critical attention than books 4 and 6. For Heinze (121-36), the agonistic scenes exemplify Virgil’s artistic principles for reshaping Homeric material. Similarly, Otis (41- 61) emphasized Virgilian characterization. Putnam (64-104) reads the games in conjunction with the Palinurus episode as a reflection on heroic sacrifice. Galinsky has emphasized the degree to which the games are interwoven with themes and diction in both book 5 and the poem as a whole. Harris, Briggs, and Feldherr have explored historical elements and Augustan political themes within the games. Farrell attempts to bring synthesis to these views by reading the games through a lens of parenthood themes. A critical observation remains missing. Water and nautical imagery are well-established metaphors for poetry and poiesis. The association is attested as early as Pindar (e.g. P. 10.51-4). In regard to neoteric and Augustan poetics, it is sufficient to recall the prominence of water in Callimachus (Ap. 105-113). This same topos lies at the foundation of Catullus 64 and appears within both the Georgics and Horace’s Odes (cf. Harrison). The agones of Aeneid 5 would be a natural moment for such motifs. Virgil introduces all four ships as equals (114). Nevertheless, the Chimaera is conspicuous for its bulk and its three-fold oars (118-20). -

Open Skoutelas Thesis.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF CLASSICS & ANCIENT MEDITERRANEAN STUDIES THE CARTOGRAPHY OF POWER IN GREEK EPIC: HOMER’S ODYSSEY & THE RECEPTION OF HOMERIC GEOGRAPHIES IN THE HELLENISTIC AND IMPERIAL PERIODS CHARISSA SKOUTELAS SPRING 2020 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in Classics & Ancient Mediterranean Studies and Global & International Studies with honors in Classics & Ancient Mediterranean Studies Reviewed and approved* by the following: Anna Peterson Tombros Early Career Professor of Classical Studies and Assistant Professor of Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies Thesis Supervisor Erin Hanses Lecturer in Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies Honors Adviser * Electronic approvals are on file. i ABSTRACT As modern scholarship has transitioned from analyzing literature in terms of its temporal components towards a focus on narrative spaces, scholars like Alex Purves and Donald Lateiner have applied this framework also to ancient Greek literature. Homer’s Odyssey provides a critical recipient for such inquiry, and Purves has explored the construction of space in the poem with relation to its implications on Greek epic as a genre. This paper seeks to expand upon the spatial discourse on Homer’s Odyssey by pinpointing the modern geographic concept of power, tracing a term inspired by Michael Foucault, or a “cartography of power,” in the poem. In Chapter 2 I employ a narratological approach to examine power dynamics played out over specific spaces of Odysseus’ wanderings, and then on Ithaca, analyzing the intersection of space, power, knowledge, and deception. The second half of this chapter discusses the threshold of Odysseus’ palace and flows of power across spheres of gender and class. -

Antrocom 4(2) 10

Antrocom 2008 - Vol 4 - n. 2 145-157 Antropologia storica Literary anthroponymy: decοding the characters of Homer’s Odyssey MARCY GEORGE-KOKKINAKI Abstract. Over the generations, people never cease to be fascinated by the epic journeys of Odysseus. Scholars seem to be divided by the vivid descriptions of Odyssey’s exotic unknown lands, extreme nature’s forces, encounters with gods, semi-gods, unusual people and mythic monsters. The present paper examines the ancient texts and demonstrates a number of original tables in order to support the etymological and grammatical analysis of the characters. Aim of this research paper is to provide a highly original and yet accurate Linguistic and Etymological Analysis of the names of the main Heroes and Peoples of Odyssey. Then Autolycus said: “My daughter’s husband and my daughter, give him whatsoever name I say. For I have been angered with many over the fruitful earth, therefore let the child be named “Odysseus”. Odyssey, Rhapsody 19, Vss 407-410 1. Introduction The most skeptical researchers consider that Odyssey is an imaginary Epic, yet written in a distinguished, articulate manner. Other researchers set their faith in Homer, and initiate a number of researches, both in ancient texts, and excavations, in a way similar to the German Archaeologist, Heinrich Schliemann (1822-1890) who as a young boy, decided to visit Asia Minor to excavate Troy, and thus confirm the reality beneath Homer’s epic writings. Finally, a third group of researchers is skeptical about the ancient epics, but would be willing to change their mind should tangible evidence be found, either in the form of archaeological findings or logical conclusions from historical evidence. -

Critic-2013-7.Pdf

Student Tickets $79 (+BF) WIN YOURSELF SOME TICKETS! TWO AWESOME CHANCES TO GET YOURSELF TO THE GIG THETHE QUESTQUEST FORFOR. THETHE ULTIMATEULTIMATE AEROGUITARSMITHAEROGUITARSMITH Thursday 18th April 12pm at Market Day RECREATERECREATE ANAN AEROSMITHAEROSMITH ANTHEMANTHEM and win your at tickets to the concert check out OUSA Facebook for details on how to win. STUDENT TICKETS $79(+BF) LIMITED NUMBERS AVAILABLE AT THIS PRICE, BOOK NOW AT FORSYTH BARR 2 | STADIUM, fb.com/critictearohi REGENT THEATRE OR THE EDGAR CENTER WITH STUDENT ID. EDITOR Callum Fredric [email protected] Issue 07 | April 15, 2013 | critic.co.nz DEPUTY EDITOR Zane Pocock [email protected] TECHNICAL EDITOR Sam Clark DESIGNER Dan Blackball 16 FEATURE WRITERS Loulou Callister-Baker, Maddy Phillipps NEWS FEATURES NEWS TEAM Zane Pocock, Claudia Herron, 06 | Anonymous Jerk Knocks 16 | Evidence of a Mid-Life Crisis Bella Macdonald Over Cones Loulou Callister-Baker discovers boxes in the attic containing evidence of a SECTION EDITORS 07 | Lord Monckton man’s mid-life crisis, complete with nude Sam McChesney, Basti Menkes, sketches and low-quality weed. Baz Macdonald, Josef Alton, 08 | Racist Danish Runs Gus Gawn, Tristan Keillor Rampant 20 | Three Fables of Dunedin’s Forgotten Flatters 09 | Driver admits liability in Shamelessly stealing Loulou’s idea, CONTRIBUTORS cycle death Callum Fredric tells three untold stories Thomas Stevenson, Josie Cochrane, from Dunedin’s past based on books and Sarah Bayly, Thomas Raethel, documents found at a friend’s flat. Sara Lamb-Miller, Jamie Breen, Catherine Poon, Nick Jolly, 26 | The Little Foetus in the Lucy Hunter, Gerard Barbalich, Pink Knitted Cap Campbell Ecklein, Jess Cole, A poem by Maddy Phillipps in memory Phoebe Harrop, Elsie Stone, of the little foetus in the pink knitted cap.