Music in Ireland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Year's Music

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com fti E Y LAKS MV5IC 1896 juu> S-q. SV- THE YEAR'S MUSIC. PIANOS FOR HIRE Cramer FOR HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY Pianos BY All THE BEQUEST OF EVERT JANSEN WENDELL (CLASS OF 1882) OF NEW YORK Makers. 1918 THIS^BQQKJS FOR USE 1 WITHIN THE LIBRARY ONLY 207 & 209, REGENT STREET, REST, E.C. A D VERTISEMENTS. A NOVEL PROGRAMME for a BALLAD CONCERT, OR A Complete Oratorio, Opera Recital, Opera and Operetta in Costume, and Ballad Concert Party. MADAME FANNY MOODY AND MR. CHARLES MANNERS, Prima Donna Soprano and Principal Bass of Royal Italian Opera, Covent Garden, London ; also of 5UI the principal ©ratorio, dJrtlustra, artii Sgmphoiu) Cxmctria of ©wat Jfvitain, Jtmmca anb Canaba, With their Full Party, comprising altogether Five Vocalists and Three Instrumentalists, Are now Booking Engagements for the Coming Season. Suggested Programme for Ballad and Opera (in Costume) Concert. Part I. could consist of Ballads, Scenas, Duets, Violin Solos, &c. Lasting for about an hour and a quarter. Part II. Opera or Operetta in Costume. To play an hour or an hour and a half. Suggested Programme for a Choral Society. Part I. A Small Oratorio work with Chorus. Part II. An Operetta in Costume; or the whole party can be engaged for a whole work (Oratorio or Opera), or Opera in Costume, or Recital. REPERTOIRE. Faust (Gounod), Philemon and Baucis {Gounod) (by arrangement with Sir Augustus Harris), Maritana (Wallace), Bohemian Girl (Balfe), and most of the usual Oratorios, &c. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

IRISH MUSIC AND HOME-RULE POLITICS, 1800-1922 By AARON C. KEEBAUGH A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Aaron C. Keebaugh 2 ―I received a letter from the American Quarter Horse Association saying that I was the only member on their list who actually doesn‘t own a horse.‖—Jim Logg to Ernest the Sincere from Love Never Dies in Punxsutawney To James E. Schoenfelder 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A project such as this one could easily go on forever. That said, I wish to thank many people for their assistance and support during the four years it took to complete this dissertation. First, I thank the members of my committee—Dr. Larry Crook, Dr. Paul Richards, Dr. Joyce Davis, and Dr. Jessica Harland-Jacobs—for their comments and pointers on the written draft of this work. I especially thank my committee chair, Dr. David Z. Kushner, for his guidance and friendship during my graduate studies at the University of Florida the past decade. I have learned much from the fine example he embodies as a scholar and teacher for his students in the musicology program. I also thank the University of Florida Center for European Studies and Office of Research, both of which provided funding for my travel to London to conduct research at the British Library. I owe gratitude to the staff at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. for their assistance in locating some of the materials in the Victor Herbert Collection. -

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst La Ttéiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’S Preludes for Piano Op.163 and Op.179: a Musicological Retrospective

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst la ttÉiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’s Preludes for Piano op.163 and op.179: A Musicological Retrospective (3 Volumes) Volume 1 Adèle Commins Thesis Submitted to the National University of Ireland, Maynooth for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music National University of Ireland, Maynooth Maynooth Co. Kildare 2012 Head of Department: Professor Fiona M. Palmer Supervisors: Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley & Dr Patrick F. Devine Acknowledgements I would like to express my appreciation to a number of people who have helped me throughout my doctoral studies. Firstly, I would like to express my gratitude and appreciation to my supervisors and mentors, Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley and Dr Patrick Devine, for their guidance, insight, advice, criticism and commitment over the course of my doctoral studies. They enabled me to develop my ideas and bring the project to completion. I am grateful to Professor Fiona Palmer and to Professor Gerard Gillen who encouraged and supported my studies during both my undergraduate and postgraduate studies in the Music Department at NUI Maynooth. It was Professor Gillen who introduced me to Stanford and his music, and for this, I am very grateful. I am grateful to the staff in many libraries and archives for assisting me with my many queries and furnishing me with research materials. In particular, the Stanford Collection at the Robinson Library, Newcastle University has been an invaluable resource during this research project and I would like to thank Melanie Wood, Elaine Archbold and Alan Callender and all the staff at the Robinson Library, for all of their help and for granting me access to the vast Stanford collection. -

Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland

COLONEL- MALCOLM- OF POLTALLOCH CAMPBELL COLLECTION Rioghachca emeaNN. ANNALS OF THE KINGDOM OF IEELAND, BY THE FOUR MASTERS, KKOM THE EARLIEST PERIOD TO THE YEAR 1616. EDITED FROM MSS. IN THE LIBRARY OF THE ROYAL IRISH ACADEMY AND OF TRINITY COLLEGE, DUBLIN, WITH A TRANSLATION, AND COPIOUS NOTES, BY JOHN O'DONOYAN, LLD., M.R.I.A., BARRISTER AT LAW. " Olim Regibus parebaut, nuuc per Principes faction! bus et studiis trahuntur: nee aliud ad versus validiasiuias gentes pro uobis utilius, qnam quod in commune non consulunt. Rarus duabus tribusve civitatibus ad propulsandum eommuu periculom conventus : ita dum singnli pugnant umVersi vincuntur." TACITUS, AQBICOLA, c. 12. SECOND EDITION. VOL. VII. DUBLIN: HODGES, SMITH, AND CO., GRAFTON-STREET, BOOKSELLERS TO THE UNIVERSITY. 1856. DUBLIN : i3tintcc at tije ffinibcrsitn )J\tss, BY M. H. GILL. INDEX LOCORUM. of the is the letters A. M. are no letter is the of Christ N. B. When the year World intended, prefixed ; when prefixed, year in is the Irish form the in is the or is intended. The first name, Roman letters, original ; second, Italics, English, anglicised form. ABHA, 1150. Achadh-bo, burned, 1069, 1116. Abhaill-Chethearnaigh, 1133. plundered, 913. Abhainn-da-loilgheach, 1598. successors of Cainneach of, 969, 1003, Abhainn-Innsi-na-subh, 1158. 1007, 1008, 1011, 1012, 1038, 1050, 1066, Abhainn-na-hEoghanacha, 1502. 1108, 1154. Abhainn-mhor, Owenmore, river in the county Achadh-Chonaire, Aclionry, 1328, 1398, 1409, of Sligo, 1597. 1434. Abhainn-mhor, The Blackwater, river in Mun- Achadh-Cille-moire,.4^az7wre, in East Brefny, ster, 1578, 1595. 1429. Abhainn-mhor, river in Ulster, 1483, 1505, Achadh-cinn, abbot of, 554. -

Miscellaneous Collection of the Terrell Family Records

MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTION OF THE TERRELL FAMILY RECORDS Publication No. 194 Compiled by Colonel Lynch Moore Terrell Ca 1910-1924 This publication has been retyped from the Original Terrell Book published ca 1910 and apparently represents a compilation of letters and papers accumulated over the years by two brothers and their cousin. They were: General William Henry Harrison Terrell 1827-1884 Indianapolis, Indiana. (His brother). Colonel Lynch Moore Terrell 1834-1924 Atlanta Georgia. Their cousin. Hon. Robert Williams Carroll 1820-1895 Cincinnati, Ohio. It is presumed that the Contents of this Book were assembled by Col. Lynch Moore Terrell some time between 1910 and 1924; after the death of Lynch’s brother and cousin. There are, among many other items, five interesting letters written to and from another cousin, Edwin Terrell 1848-1910 (Ambassador to Belgium 1889-1893), San Antonio, Texas. During this period when Edwin was Ambassador, Edwin became acquainted with Joseph Henry Terrell b 1863, Keswick, England. Joseph published in 1904 the best Tyrrell book on the English Terrells. It appears that Edwin and Joseph exchanged information on Terrell genealogy for both American and English Terrells. Publication No. 194 Published by the Terrell Society of America, Inc. Cairo GA USA 2001 I N D E X Introductory Note.. 1 Nomenclature-Origin and Personal Characteristics of the Terrells . 3 Physical Types and Personal Characteristics of the Terrells 7 List of Wills proved to the Name of Terrell Tyrrell)-(With its Variations in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury 1383-1700. 9 Extracts from the records of Caroline County and Cedar Creek, Virginia, Meetings, Society of Friends, respecting the Terrell Family . -

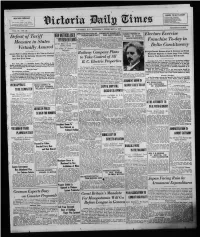

Defeat of Tariff Measure in States Virtually Assured Electors

WHERE TO GO TO-NIGHT Columbia—Big Happiness. Variety—A House Divided. WEATHER FORECAST Princess—Sylvia Runs Away. Royal—Harriet and the Bluer. Dominion—The Charm School. Pantages—Vaudeville. For 36 hours ending 6 p.m. Friday: Romano—The Restless Sex. Victoria and vicinity—Southerly winds, unsettled and mild, with rain. rna SIXTEEN PAGES VICTORIA, B. C., THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 3, 1921 VOL. 58. NO. 28 ARRESTED FOR STEALING PREMIER OF QUEENSLAND FORMER PREMIER OF Electors Exercise RUSSIAN SABLE COAT SEES ASIATIC MENACE POLAND TO STATES; Defeat of Tariff Toronto, Feb. 3.—^Tilliam Cowan, Brisbane* Queensland, Feb. 3. Pre IGNACE PADEREWSKI of Montreal, is under arrest in Mon mier E. G? Theodore declared to-day treal on a charge of stealing a Royal that anyone who doubted that Aus Franchise To-day in Russian sable coat valued at $3,500 tralians would soon be called upon to from a wagon at the Toronto store Measure in States of the Holt Renfrew Company on defend their homes against Asiatic Lorries Blown Up by Mine; September 30 last. The coat, which I invasion, was living in a fool’s para was recovered in Montreal, had been dise. Asiatic ideals and aspirations, Bombs Hurled he added, were a menace to the Ideals Delta Constituency through the Boxer Rebellion in [ of the Australian Labor Party. Virtually Assured Four Killed in Ambush at China. Ballinalee Straight Contest Between Alex. D. Paterson and Frank Dublin, Feb. 3.—Four men are Railway Company Plans Senate Fails to Adopt Closure to Get Vote on Fordney dead as a result of an ambush of a Mackenzie Expected to Draw Large Vote; Polling squad of auxiliary police at Bal Bill; Will Not Be Seriously Pressed For Passage, liqalee near here yesterday, two of Returns From Remote Stations Will Be Late. -

<Insert Image Cover>

An Chomhaırle Ealaíon An Tríochadú Turascáil Bhliantúil, maille le Cuntais don bhliain dar chríoch 31ú Nollaig 1981. Tíolacadh don Rialtas agus leagadh faoi bhráid gach Tí den Oireachtas de bhun Altanna 6 (3) agus 7 (1) den Acht Ealaíon 1951. Thirtieth Annual Report and Accounts for the year ended 31st December 1981. Presented to the Government and laid before each House of the Oireachtas pursuant to Sections 6 (3) and 7 (1) of the Arts Act, 1951. Cover: Photograph by Thomas Grace from the Arts Council touring exhibition of Irish photography "Out of the Shadows". Members James White, Chairman Brendan Adams (until October) Kathleen Barrington Brian Boydell Máire de Paor Andrew Devane Bridget Doolan Dr. J. B. Kearney Hugh Maguire (until December) Louis Marcus (until December) Seán Ó Tuama (until January) Donald Potter Nóra Relihan Michael Scott Richard Stokes Dr. T. J. Walsh James Warwick Staff Director Colm Ó Briain Drama and Dance Officer Arthur Lappin Opera and Music Officer Marion Creely Traditional Music Officer Paddy Glackin Education and Community Arts Officer Adrian Munnelly Literature and Combined Arts Officer Laurence Cassidy Visual Arts Officer/Grants Medb Ruane Visual Arts Officer/Exhibitions Patrick Murphy Finance and Regional Development Officer David McConnell Administration, Research and Film Officer David Kavanagh Administrative Assistant Nuala O'Byrne Secretarial Assistants Veronica Barker Patricia Callaly Antoinette Dawson Sheilah Harris Kevin Healy Bernadette O'Leary Receptionist Kathryn Cahille 70 Merrion Square, Dublin 2. Tel: (01) 764685. An Chomhaırle Ealaíon An Chomhairle Ealaíon/The Arts Council is an independent organization set up under the Arts Acts 1951 and 1973 to promote the arts. -

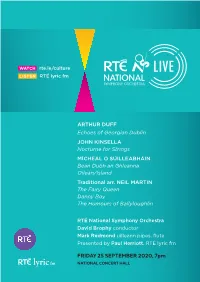

RTE NSO 25 Sept Prog.Qxp:Layout 1

WATCH rte.ie/culture LISTEN RTÉ lyric fm ARTHUR DUFF Echoes of Georgian Dublin JOHN KINSELLA Nocturne for Strings MÍCHEÁL Ó SÚILLEABHÁIN Bean Dubh an Ghleanna Oileán/Island Traditional arr. NEIL MARTIN The Fairy Queen Danny Boy The Humours of Ballyloughlin RTÉ National Symphony Orchestra David Brophy conductor Mark Redmond uilleann pipes, flute Presented by Paul Herriott, RTÉ lyric fm FRIDAY 25 SEPTEMBER 2020, 7pm NATIONAL CONCERT HALL 1 Arthur Duff 1899-1956 Echoes of Georgian Dublin i. In College Green ii. Song for Amanda iii. Minuet iv. Largo (The tender lover) v. Rigaudon Arthur Duff showed early promise as a musician. He was a chorister at Dublin’s Christ Church Cathedral and studied at the Royal Irish Academy of Music, taking his degree in music at Trinity College, Dublin. He was later awarded a doctorate in music in 1942. Duff had initially intended to enter the Church of Ireland as a priest, but abandoned his studies in favour of a career in music, studying composition for a time with Hamilton Harty. He was organist and choirmaster at Christ Church, Bray, for a short time before becoming a bandmaster in the Army School of Music and conductor of the Army No. 2 band based in Cork. He left the army in 1931, at the same time that his short-lived marriage broke down, and became Music Director at the Abbey Theatre, writing music for plays such as W.B. Yeats’s The King of the Great Clock Tower and Resurrection, and Denis Johnston’s A Bride for the Unicorn. The Abbey connection also led to the composition of one of Duff’s characteristic works, the Drinking Horn Suite (1953 but drawing on music he had composed twenty years earlier as a ballet score). -

Intimations Surnames L

Intimations Extracted from the Watt Library index of family history notices as published in Inverclyde newspapers between 1800 and 1918. Surnames L This index is provided to researchers as a reference resource to aid the searching of these historic publications which can be consulted on microfiche, preferably by prior appointment, at the Watt Library, 9 Union Street, Greenock. Records are indexed by type: birth, death and marriage, then by surname, year in chronological order. Marriage records are listed by the surnames (in alphabetical order), of the spouses and the year. The copyright in this index is owned by Inverclyde Libraries, Museums and Archives to whom application should be made if you wish to use the index for any commercial purpose. It is made available for non- commercial use under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 License). This document is also available in Open Document Format. Surnames L Record Surname When First Name Entry Type Marriage L’AMY / SCOTT 1863 Sylvester L’Amy, London, to Margaret Sinclair, 2nd daughter of John Scott, Finnart, Greenock, at St George’s, London on 6th May 1863.. see Margaret S. (Greenock Advertiser 9.5.1863) Marriage LACHLAN / 1891 Alexander McLeod to Lizzie, youngest daughter of late MCLEOD James Lachlan, at Arcade Hall, Greenock on 5th February 1891 (Greenock Telegraph 09.02.1891) Marriage LACHLAN / SLATER 1882 Peter, eldest son of John Slater, blacksmith to Mary, youngest daughter of William Lachlan formerly of Port Glasgow at 9 Plantation Place, Port Glasgow on 21.04.1882. (Greenock Telegraph 24.04.1882) see Mary L Death LACZUISKY 1869 Maximillian Maximillian Laczuisky died at 5 Clarence Street, Greenock on 26th December 1869. -

Séamas De Barra

1 Séamas de Barra Aloys Fleischmann Field Day Music Aloys Fleischmann (1910–92) was a key figure in the musical General Editors: Séamas de Barra and Patrick Zuk Séamas de Barra life of twentieth-century Ireland. Séamas de Barra presents an authoritative and insightful account of Fleischmann’s career 1. Aloys Fleischmann (2006), Séamas de Barra as a composer, conductor, teacher and musicologist, situating 2. Raymond Deane (2006), Patrick Zuk his achievements in wider social and intellectual contexts, and paying particular attention to his lifelong engagement Among forthcoming volumes are studies of Ina Boyle, Seóirse with Gaelic culture and his attempts to forge a distinctively Bodley, Michele Esposito and James Wilson. Aloys Irish music. Fleischmann Séamas de Barra is a composer and a musicologist. Music/Contemporary Ireland FIELD DAY PUBLICATIONS MUSIC 1 Séamas de Barra Aloys Fleischmann Field Day Music Aloys Fleischmann (1910–92) was a key figure in the musical General Editors: Séamas de Barra and Patrick Zuk Séamas de Barra life of twentieth-century Ireland. Séamas de Barra presents an authoritative and insightful account of Fleischmann’s career 1. Aloys Fleischmann (2006), Séamas de Barra as a composer, conductor, teacher and musicologist, situating 2. Raymond Deane (2006), Patrick Zuk his achievements in wider social and intellectual contexts, and paying particular attention to his lifelong engagement Among forthcoming volumes are studies of Ina Boyle, Seóirse with Gaelic culture and his attempts to forge a distinctively Bodley, Michele Esposito and James Wilson. Aloys Irish music. Fleischmann Séamas de Barra is a composer and a musicologist. Music/Contemporary Ireland FIELD DAY PUBLICATIONS MUSIC Aloys Fleischmann i ii Aloys Fleischmann Aloys Fleischmann Aloys Fleischmann Aloys Fleischmann Séamas de Barra Field Day Music 1 Series Editors: Séamas de Barra and Patrick Zuk Field Day Publications Dublin, 2006 Séamas de Barra has asserted his right under the Copyright and Related Rights Act, 2000, to be identified as the author of this work. -

YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 Frontispiece: Derry Jeffares Beside the Edmund Dulac Memorial Stone to W

To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/194 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the same series YEATS ANNUALS Nos. 1, 2 Edited by Richard J. Finneran YEATS ANNUALS Nos. 3-8, 10-11, 13 Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS AND WOMEN: YEATS ANNUAL No. 9: A Special Number Edited by Deirdre Toomey THAT ACCUSING EYE: YEATS AND HIS IRISH READERS YEATS ANNUAL No. 12: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould and Edna Longley YEATS AND THE NINETIES YEATS ANNUAL No. 14: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS’S COLLABORATIONS YEATS ANNUAL No. 15: A Special Number Edited by Wayne K. Chapman and Warwick Gould POEMS AND CONTEXTS YEATS ANNUAL No. 16: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould INFLUENCE AND CONFLUENCE: YEATS ANNUAL No. 17: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 Frontispiece: Derry Jeffares beside the Edmund Dulac memorial stone to W. B. Yeats. Roquebrune Cemetery, France, 1986. Private Collection. THE LIVING STREAM ESSAYS IN MEMORY OF A. NORMAN JEFFARES YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 A Special Issue Edited by Warwick Gould http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2013 Gould, et al. (contributors retain copyright of their work). The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Licence. This licence allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text. -

Ireland: in Search of Reform for Public Service Media Funding

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Ulster University's Research Portal Ireland: In search of reform for public service media funding Phil Ramsey, Ulster University [email protected] http://ulster.academia.edu/PhilRamsey | http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5873-489X Published as: Ramsey, P. (2018) Ireland: In search of reform for public service media funding. In C. Herzog, H. Hilker, L. Novy and Torun, O. (Eds), Transparency and Funding of Public Service Media: deutsche Debatte im internationalen Kontex (pp.77–90). Wiesbaden: Springer VS. Abstract This chapter discusses public service media (PSM) in Ireland in the context of the recent financial crisis and major demographic changes. It considers some of the factors impacting domestic PSM that are similar to those in other mature media systems in Europe, such as declining funding streams and debates over PSM-funding reform. After introducing the Irish social and political-economic context and providing for a brief historical review of PSM in Ireland, the roles of the domestic PSM organizations RTÉ and TG4 in the Irish media market are discussed. The chapter addresses initial government support for the introduction of a German-style household media fee, a Public Service Broadcasting Charge. While the charge was intended for introduction in 2015, it was later ruled out by the Irish Government in 2016. Ireland: in search of reform for public service media funding Public Service Media (PSM) has a long-tradition in the Republic of Ireland (ROI, hereafter Ireland), dating back to the commencement of the state radio service 2RN in January 1926.1 The state’s involvement in broadcasting later gave way to the main public broadcaster RTÉ, which has broadcast simultaneously on television and radio since New Year’s Eve 1961, and latterly, delivered public service content online.