Peter Sculthorpe's String Quartet No. 14: a Musical Response to Social

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Benevolent Colonizers in Nineteenth-Century Australia Quaker Lives and Ideals

Benevolent Colonizers in Nineteenth-Century Australia Quaker Lives and Ideals Eva Bischoff Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series Series Editors Richard Drayton Department of History King’s College London London, UK Saul Dubow Magdalene College University of Cambridge Cambridge, UK The Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies series is a collection of studies on empires in world history and on the societies and cultures which emerged from colonialism. It includes both transnational, comparative and connective studies, and studies which address where particular regions or nations participate in global phenomena. While in the past the series focused on the British Empire and Commonwealth, in its current incarna- tion there is no imperial system, period of human history or part of the world which lies outside of its compass. While we particularly welcome the first monographs of young researchers, we also seek major studies by more senior scholars, and welcome collections of essays with a strong thematic focus. The series includes work on politics, economics, culture, literature, science, art, medicine, and war. Our aim is to collect the most exciting new scholarship on world history with an imperial theme. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/13937 Eva Bischoff Benevolent Colonizers in Nineteenth- Century Australia Quaker Lives and Ideals Eva Bischoff Department of International History Trier University Trier, Germany Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series ISBN 978-3-030-32666-1 ISBN 978-3-030-32667-8 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32667-8 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2020 This work is subject to copyright. -

LS17.17022-Program-Web

ACTEWAGL LLEWELLYN SERIES CELLO The CSO is assisted by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body New Combination “Bean” Lorry No.341 commissioned 31st December 1925. 115 YEARS OF POWERING PROGRESS TOGETHER Since 1901, Shell has invested in large projects which have contributed to the prosperity of the Australian economy. We value our partnerships with communities, governments and industry. And celebrate our longstanding partnership with the Canberra Symphony Orchestra. shell.com.au Photograph courtesy of The University of Melbourne Archives 2008.0045.0601 SHA3106__CSO_245x172_V3.indd 1 20/09/2016 2:53 PM ACTEWAGL LLEWELLYN SERIES CELLO Wednesday 17 May & Thursday 18 May, 2017 Llewellyn Hall, ANU 7.30pm Conductor Stanley Dodds Cello Umberto Clerici ----- HAYDN: Overture to L’isola disabitata (The Desert Island), Hob 28/9 8’ SCHUMANN: Cello Concerto in A minor, op. 129 25’ 1. Nicht zu schnell 2. Langsam 3. Sehr lebhaft INTERMISSION SCULTHORPE: String Sonata No. 3 (Jabiru Dreaming) 8’ 1 Deciso 2 Liberamente – Estatico BRAHMS: Symphony No. 3 in F major, op. 90 33’ 1. Allegro con brio 2. Andante 3. Poco allegretto 4. Allegro Please note: this program is correct at time of printing, however it is subject to change without notice. Umberto Clerici’s performance is supported by the Embassy of Italy in Canberra, Istituto Italiano di Cultura in Sydney and Schiavello enterprise Cover photo by Sarah Walker Sarah Cover photo by 17022 SEASON 2017 ActewAGL Llewellyn Series: Cello, Horn, Violin “Music -

Joana Carneiro Music Director

JOANA CARNEIRO MUSIC DIRECTOR Berkeley Symphony 17/18 Season 5 Message from the Music Director 7 Message from the Board President 9 Message from the Executive Director 11 Board of Directors & Advisory Council 12 Orchestra 15 Season Sponsors 16 Berkeley Sound Composer Fellows & Full@BAMPFA 18 Berkeley Symphony 17/18 Calendar 21 Tonight’s Program 23 Program Notes 37 About Music Director Joana Carneiro 39 Guest Artists & Composers 43 About Berkeley Symphony 44 Music in the Schools 47 Berkeley Symphony Legacy Society 49 Annual Membership Support 58 Broadcast Dates 61 Contact 62 Advertiser Index Media Sponsor Gertrude Allen • Annette Campbell-White & Ruedi Naumann-Etienne Official Wine Margaret Dorfman • Ann & Gordon Getty • Jill Grossman Sponsor Kathleen G. Henschel & John Dewes • Edith Jackson & Thomas W. Richardson Sarah Coade Mandell & Peter Mandell • Tricia Swift S. Shariq Yosufzai & Brian James Presentation bouquets are graciously provided by Jutta’s Flowers, the official florist of Berkeley Symphony. Berkeley Symphony is a member of the League of American Orchestras and the Association of California Symphony Orchestras. No photographs or recordings of any part of tonight’s performance may be made without the written consent of the management of Berkeley Symphony. Program subject to change. October 5 & 6, 2017 3 4 October 5 & 6, 2017 Message from the Music Director Dear Friends, Happy New Season 17/18! I am delighted to be back in Berkeley after more than a year. There are three beautiful reasons for photo by Rodrigo de Souza my hiatus. I am so grateful for all the support I received from the Berkeley Symphony musicians, members of the Board and Advisory Council, the staff, and from all of you throughout this special period of my family’s life. -

Intimacies of Violence in the Settler Colony Economies of Dispossession Around the Pacific Rim

Cambridge Imperial & Post-Colonial Studies INTIMACIES OF VIOLENCE IN THE SETTLER COLONY ECONOMIES OF DISPOSSESSION AROUND THE PACIFIC RIM EDITED BY PENELOPE EDMONDS & AMANDA NETTELBECK Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series Series Editors Richard Drayton Department of History King’s College London London, UK Saul Dubow Magdalene College University of Cambridge Cambridge, UK The Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies series is a collection of studies on empires in world history and on the societies and cultures which emerged from colonialism. It includes both transnational, comparative and connective studies, and studies which address where particular regions or nations participate in global phenomena. While in the past the series focused on the British Empire and Commonwealth, in its current incarna- tion there is no imperial system, period of human history or part of the world which lies outside of its compass. While we particularly welcome the first monographs of young researchers, we also seek major studies by more senior scholars, and welcome collections of essays with a strong thematic focus. The series includes work on politics, economics, culture, literature, science, art, medicine, and war. Our aim is to collect the most exciting new scholarship on world history with an imperial theme. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/13937 Penelope Edmonds Amanda Nettelbeck Editors Intimacies of Violence in the Settler Colony Economies of Dispossession around the Pacific Rim Editors Penelope Edmonds Amanda Nettelbeck School of Humanities School of Humanities University of Tasmania University of Adelaide Hobart, TAS, Australia Adelaide, SA, Australia Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series ISBN 978-3-319-76230-2 ISBN 978-3-319-76231-9 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-76231-9 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018941557 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2018 This work is subject to copyright. -

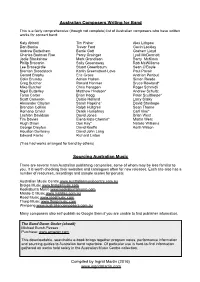

Australian Composers & Sourcing Music

Australian Composers Writing for Band This is a fairly comprehensive (though not complete) list of Australian composers who have written works for concert band: Katy Abbott Tim Fisher Alex Lithgow Don Banks Trevor Ford Gavin Lockley Andrew Batterham Barrie Gott Graham Lloyd Charles Bodman Rae Percy Grainger Lyall McDermott Jodie Blackshaw Mark Grandison Barry McKimm Philip Bracanin Sally Greenaway Rob McWilliams Lee Bracegirdle Stuart Greenbaum Sean O’Boyle Brenton Broadstock Karlin Greenstreet-Love Paul Pavoir Gerard Brophy Eric Gross Andrian Pertout Colin Brumby Adrian Hallam Simon Reade Greg Butcher Ronald Hanmer Bruce Rowland* Mike Butcher Chris Henzgen Roger Schmidli Nigel Butterley Matthew Hindson* Andrew Schultz Taran Carter Brian Hogg Peter Sculthorpe* Scott Cameron Dulcie Holland Larry Sitsky Alexander Clayton Sarah Hopkins* David Stanhope Brendan Collins Ralph Hultgren Sean Thorne Romano Crivici Derek Humphrey Carl Vine* Lachlan Davidson David Jones Brian West Tim Davies Elena Kats-Chernin* Martin West Hugh Dixon Don Kay* Natalie Williams George Dreyfus David Keeffe Keith Wilson Houston Dunleavy David John Lang Edward Fairlie Richard Linton (*has had works arranged for band by others) Sourcing Australian Music There are several main Australian publishing companies, some of whom may be less familiar to you. It is worth checking their websites and catalogues often for new releases. Each site also has a number of resources, recordings and sample scores for perusal. Australian Music Centre www.australianmusiccentre.com.au Brolga Music www.brolgamusic.com Kookaburra Music www.kookaburramusic.com Middle C Music www.middlec.com.au Reed Music www.reedmusic.com Thorp Music www.thorpmusic.com Wirripang www.australiancomposers.com.au Many composers also self-publish so Google them if you are unable to find publisher information. -

INSIDE the MUSICIAN: JOHN CLARE at 75 by John Clare*

INSIDE THE MUSICIAN: JOHN CLARE AT 75 by John Clare* __________________________________________________ INSIDE THE MUSICIAN is a series of articles on the Music Trust of Australia website by music people of all kinds, revealing something about their musical worlds and how they experience them. This article appeared on June 5, 2016. To read this on that website, go to this link http://musictrust.com.au/loudmouth/inside-the-musician-john-clare-75/ o come in from a wide or oblique angle, I need to apologise briefly that my writing is not what it was. There is no excuse, but a reason of sorts. Over the T past few years I have lost a son and a sister, the wonderful old Chinese lady upstairs who died and was replaced by a crazy and nasty woman who fire bombed my flat while I was visiting my daughter in Brisbane. And more, but we’ll leave that. Perhaps this stress and distress is behind my two strokes and a triple A operation (aortic aneurism in the aorta) which comprehensively relieved me of my memory for a while. Concentration is difficult and death seems often to be hovering. Yet strangely I am very fit and can race up very steep hills on my bike or grind up on the seat. It is when I am lying down and for some time afterward that it surrounds me. We’ll leave it at that. More important than that is how music sounds and what it means in what may well be the end days. Mine anyway. Like vapour trails soaring straight up at space from the horizon, or so it seems, but finding the curvature of the earth almost directly above. -

Voices of Aboriginal Tasmania Ningina Tunapri Education

voices of aboriginal tasmania ningenneh tunapry education guide Written by Andy Baird © Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery 2008 voices of aboriginal tasmania ningenneh tunapry A guide for students and teachers visiting curricula guide ningenneh tunapry, the Tasmanian Aboriginal A separate document outlining the curricula links for exhibition at the Tasmanian Museum and the ningenneh tunapry exhibition and this guide is Art Gallery available online at www.tmag.tas.gov.au/education/ Suitable for middle and secondary school resources Years 5 to 10, (students aged 10–17) suggested focus areas across the The guide is ideal for teachers and students of History and Society, Science, English and the Arts, curricula: and encompasses many areas of the National Primary Statements of Learning for Civics and Citizenship, as well as the Tasmanian Curriculum. Oral Stories: past and present (Creation stories, contemporary poetry, music) Traditional Life Continuing Culture: necklace making, basket weaving, mutton-birding Secondary Historical perspectives Repatriation of Aboriginal remains Recognition: Stolen Generation stories: the apology, land rights Art: contemporary and traditional Indigenous land management Activities in this guide that can be done at school or as research are indicated as *classroom Activites based within the TMAG are indicated as *museum Above: Brendon ‘Buck’ Brown on the bark canoe 1 voices of aboriginal tasmania contents This guide, and the new ningenneh tunapry exhibition in the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, looks at the following -

Black and White Children in Welfare in New South Wales and Tasmania, 1880-1940

‘Such a Longing’ Black and white children in welfare in New South Wales and Tasmania, 1880-1940 Naomi Parry PhD August 2007 THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Parry First name: Naomi Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: PhD School: History Faculty: Arts and Social Sciences Title: ‘Such a longing’: Black and white children in welfare in New South Wales and Tasmania, 1880-1940 Abstract 350 words maximum: When the Human Rights and Equal Opportunities Commission tabled Bringing them home, its report into the separation of indigenous children from their families, it was criticised for failing to consider Indigenous child welfare within the context of contemporary standards. Non-Indigenous people who had experienced out-of-home care also questioned why their stories were not recognised. This thesis addresses those concerns, examining the origins and history of the welfare systems of NSW and Tasmania between 1880 and 1940. Tasmania, which had no specific policies on race or Indigenous children, provides fruitful ground for comparison with NSW, which had separate welfare systems for children defined as Indigenous and non-Indigenous. This thesis draws on the records of these systems to examine the gaps between ideology and policy and practice. The development of welfare systems was uneven, but there are clear trends. In the years 1880 to 1940 non-Indigenous welfare systems placed their faith in boarding-out (fostering) as the most humane method of caring for neglected and destitute children, although institutions and juvenile apprenticeship were never supplanted by fostering. Concepts of child welfare shifted from charity to welfare; that is, from simple removal to social interventions that would assist children's reform. -

The Utilization of Truganini's Human Remains in Colonial Tasmania

History of Anthropology Newsletter Volume 39 Issue 1 June 2012 Article 3 January 2012 The Utilization of Truganini's Human Remains in Colonial Tasmania Antje Kühnast Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/han Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Recommended Citation Kühnast, Antje (2012) "The Utilization of Truganini's Human Remains in Colonial Tasmania," History of Anthropology Newsletter: Vol. 39 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/han/vol39/iss1/3 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/han/vol39/iss1/3 For more information, please contact [email protected]. History of Anthropology Newsletter 39.1 (June 2012) / 3 1 The Utilization of Truganini’s Human Remains in Colonial Tasmania Antje Kühnast, University of New South Wales, [email protected] Between 1904 and 1947, visitors to the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery in Hobart who stepped into the Aboriginal exhibition room were instantly confronted with the death of their colony’s indigenous population—or so they were led to believe. Their gaze encountered a glass case presenting the skeleton of “Truganini, The Last Tasmanian Aboriginal” (advertisement, June 24, 1905). Also known as “Queen Truganini” at her older age, representations of her reflect the many, often contradictory, interpretations of her life and agency in colonial Tasmania. She has been depicted as selfish collaborator with the colonizer, savvy savior of her race, callous resistance fighter, promiscuous prostitute who preferred whites instead of her “own” men (e.g. Rae-Ellis, 1981), and “symbol for struggle and survival” (Ryan, 1996). -

Indigenous Knowledge in the Built Environment a Guide for Tertiary Educators

Indigenous Knowledge in The Built Environment A Guide for Tertiary Educators David S Jones, Darryl Low Choy, Richard Tucker, Scott Heyes, Grant Revell & Susan Bird Support for the production of this publication has been 2018 provided by the Australian Government Department of Education and Training. The views expressed in this report do ISBN not necessarily reflect the views of the Australian Government 978-1-76051-164-7 [PRINT], Department of Education and Training. 978-1-76051-165-4 [PDF], With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and 978-1-76051-166-1 [DOCX] where otherwise noted, all material presented in this document is provided under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 Citation: International License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Jones, DS, D Low Choy, R Tucker, SA Heyes, G Revell & S Bird by-sa/4.0/ (2018), Indigenous Knowledge in the Built Environment: A Guide The details of the relevant licence conditions are available on for Tertiary Educators. Canberra, ACT: Australian Government the Creative Commons website (accessible using the links Department of Education and Training. provided) as is the full legal code for the Creative Commons Attribution- ShareAlike 4.0 International License http:// Warning: creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/legalcode Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are warned that the following document may contain images and names of Requests and inquiries concerning these rights should be deceased persons. addressed to: Office for Learning and Teaching A Note on the Project’s Peer Review Process: Department of Education The content of this teaching guide has been independently GPO Box 9880, peer reviewed by five Australian academics that specialise Location code N255EL10 in the teaching of Indigenous knowledge systems within the Sydney NSW 2001 built environment professions, two of which are Aboriginal [email protected] academics and practitioners. -

Only the Dead

SCREEN AUSTRALIA PRESENTS IN ASSOCIATION WITH SCREEN QUEENSLAND AND FOXTEL A PENANCE FILMS / WOLFHOUND PICTURES PRODUCTION ONLY THE DEAD PRODUCTION NOTES Running time: 77:11 ONLY THE DEAD Directed by BILL GUTTENTAG and MICHAEL WARE Written by MICHAEL WARE Produced by PATRICK MCDONALD Produced by MICHAEL WARE Executive Producer JUSTINE A. ROSENTHAL Editor JANE MORAN Music by MICHAEL YEZERSKI Associate Producer ANDREW MACDONALD • SCREEN AUSTRALIA /PRESENTS A PENANCE FILMS / WOLFHOUND PICTURES PRODUCTION IN ASSOCIATION WITH SCREEN QUEENSLAND AND FOXTEL ONLY THE DEAD One Line Synopsis What happens when one of the most feared, most hated terrorists on the planet chooses you—personally—to reveal his arrival on the global stage? All in the midst of the American war in Iraq? Short Synopsis Theatrical feature documentary Only the Dead is the story of what happens when one ordinary man, an Australian journalist transplanted into the Middle East by the reverberations of 9/11, butts into history. It is a journey that courses through the deepest recesses of the Iraq war, revealing a darkness lurking in his own heart. A darkness that he never knew was there. The invasion of Iraq has ended, and the Americans are celebrating victory. The year is 2003. The international press corps revel in the Baghdad “Summer of Love”, there is barely a spare hotel room in the entire city. Reporters of all nationalities scramble for stories; of the abuses of Saddam’s fallen regime; of WMD’s, of reconstruction, of liberation. There are pool parties, and restaurant outings, and dinner-party circuits. Occasionally, Coalition forces are attacked, but always elsewhere, somewhere in the background. -

Aboriginal Australia: an Economic History of Failed Welfare Policy

ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIA: AN ECONOMIC HISTORY OF FAILED WELFARE POLICY Laura Davidoff and Alan Duhs* University of Queensland June 2008 Abstract: Aboriginal welfare policy of recent decades has been widely rejected as a failure. Radically different policies are now being trialed, in recognition of the continuing large gap between indigenous and non-indigenous living standards. Some Aboriginal leaders themselves have called for a rejection of the passive welfare policies of the past, in acceptance of a Friedman-style critique of ‘money for nothing’ welfare handouts, while nonetheless calling for a Sen-style capabilities approach to the policy needs of the future. *Laura Davidoff was formerly an economic consultant and is now a tutor, School of Economics The University of Queensland. *Alan Duhs is Senior Lecturer, School of Economics The University of Queensland I. Introduction: Australia’s Aboriginal population has just passed the half million mark, representing some 2.5% of the total population of about 21 million. In the midst of Australian prosperity and its world-class health and education systems lies what is now widely regarded as the national shame of Aboriginal living conditions. Particularly in remote areas, Aboriginal circumstances are so conspicuously unsatisfactory that critics regard the Aboriginal population as comprising something of a separate third world country, within the Australian mainstream. Respected Aboriginal leader Noel Pearson has described life in his North Queensland hometown as “a living Hell”. An immediate indicator of this situation is the fact the full-blooded Aborigines were not even counted in the Australian population census until a referendum changed the Australian constitution in 1967.