Echoes of Aristotle in Romans 2:14– 15: Or, Maybe Abimelech Was Not So Bad C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Romans 7 and Sanctification by Andy Woods

Romans 7 and Sanctification by Andy Woods Introduction This article will argue that one’s understanding of practical sanctification is profoundly impacted by how one views the “I” in Romans 7:7-25. Specifically, the article will argue that the “I” in Romans 7 is Paul, and in verses 14-25 Paul is reflecting upon his post conversion experience. In addition, the article will maintain that a post conversion view of Romans 7:14-25 leads to a dual nature view of the believer. This view teaches that although the believer has a new nature that he received at conversion, his Adamic nature still exists within him and continues to tempt him to return to his former sinful lifestyle throughout the course of this life. Finally, the article will contend that viewing believers through the lenses of the dual nature view shapes one’s understanding of practical sanctification in several important ways. Who is the Speaker in Romans 7:7-25? Three options for the speaker in Romans 7:7-25 have been proposed.1 First, some have proposed the theory of the Rhetorical “I”. According to this view, the pronoun “I” in Romans 7:7-25 serves as a literary device that depicts all of humanity. Thus, the “I” is not autobiographical but rather represents the experience of everyone. Second, others have proposed the theory of the Representative “I”. According to this view, the pronoun “I” in Romans 7:7-25 depicts the life experience of a representative figure that is typical of every person including the speaker. For example, the “I” of Romans 7:7-25 could represent the experience of Adam at the time of the fall. -

Official Handbook of Rules and Regulations

OFFICIAL HANDBOOK OF RULES AND REGULATIONS 2021 | 69th EDITION AMERICAN QUARTER HORSE An American Quarter Horse possesses acceptable pedigree, color and mark- ings, and has been issued a registration certificate by the American Quarter Horse Association. This horse has been bred and developed to have a kind and willing disposition, well-balanced conformation and agile speed. The American Quarter Horse is the world’s most versatile breed and is suited for a variety of purposes - from working cattle on ranches to international reining competition. There is an American Quarter Horse for every purpose. AQHA MISSION STATEMENT • To record and preserve the pedigrees of the American Quarter Horse, while maintaining the integrity of the breed and welfare of its horses. • To provide beneficial services for its members that enhance and encourage American Quarter Horse ownership and participation. • To develop diverse educational programs, material and curriculum that will position AQHA as the leading resource organization in the equine industry. • To generate growth of AQHA membership via the marketing, promo- tion, advertising and publicity of the American Quarter Horse. • To ensure the American Quarter Horse is treated humanely, with dignity, respect and compassion, at all times. FOREWORD The American Quarter Horse Association was organized in 1940 to collect, record and preserve the pedigrees of American Quarter Horses. AQHA also serves as an information center for its members and the general public on matters pertaining to shows, races and projects designed to improve the breed and aid the industry, including seeking beneficial legislation for its breeders and all horse owners. AQHA also works to promote horse owner- ship and to grow markets for American Quarter Horses. -

HORSES, KENTUCKY DERBY (1875-2019) Kentucky Derby

HORSES, KENTUCKY DERBY (1875-2019) Kentucky Derby Winners, Alphabetically (1875-2019) HORSE YEAR HORSE YEAR Affirmed 1978 Kauai King 1966 Agile 1905 Kingman 1891 Alan-a-Dale 1902 Lawrin 1938 Always Dreaming 2017 Leonatus 1883 Alysheba 1987 Lieut. Gibson 1900 American Pharoah 2015 Lil E. Tee 1992 Animal Kingdom 2011 Lookout 1893 Apollo (g) 1882 Lord Murphy 1879 Aristides 1875 Lucky Debonair 1965 Assault 1946 Macbeth II (g) 1888 Azra 1892 Majestic Prince 1969 Baden-Baden 1877 Manuel 1899 Barbaro 2006 Meridian 1911 Behave Yourself 1921 Middleground 1950 Ben Ali 1886 Mine That Bird 2009 Ben Brush 1896 Monarchos 2001 Big Brown 2008 Montrose 1887 Black Gold 1924 Morvich 1922 Bold Forbes 1976 Needles 1956 Bold Venture 1936 Northern Dancer-CAN 1964 Brokers Tip 1933 Nyquist 2016 Bubbling Over 1926 Old Rosebud (g) 1914 Buchanan 1884 Omaha 1935 Burgoo King 1932 Omar Khayyam-GB 1917 California Chrome 2014 Orb 2013 Cannonade 1974 Paul Jones (g) 1920 Canonero II 1971 Pensive 1944 Carry Back 1961 Pink Star 1907 Cavalcade 1934 Plaudit 1898 Chant 1894 Pleasant Colony 1981 Charismatic 1999 Ponder 1949 Chateaugay 1963 Proud Clarion 1967 Citation 1948 Real Quiet 1998 Clyde Van Dusen (g) 1929 Regret (f) 1915 Count Fleet 1943 Reigh Count 1928 Count Turf 1951 Riley 1890 Country House 2019 Riva Ridge 1972 Dark Star 1953 Sea Hero 1993 Day Star 1878 Seattle Slew 1977 Decidedly 1962 Secretariat 1973 Determine 1954 Shut Out 1942 Donau 1910 Silver Charm 1997 Donerail 1913 Sir Barton 1919 Dust Commander 1970 Sir Huon 1906 Elwood 1904 Smarty Jones 2004 Exterminator -

Getting Romans to the Right Romans: Phoebe and the Delivery of Paul’S Letter

GETTING ROMANS TO THE RIGHT ROMANS: PHOEBE AND THE DELIVERY OF PAUL’S LETTER Allan Chapple Summary How did Romans reach the people for whom it was intended? There is widespread agreement that Phoebe was the bearer of the letter (Rom. 16:1-2), but little investigation of or agreement about the exact nature of her responsibilities. By exploring the data available to us, especially tha found in Romans 16, this essay provides a reconstruction of the events surrounding the transport and delivery of the letter to the Roman Christians. In particular, it proposes the following: Phoebe conveyed the letter to Rome, probably by sea; the church in Rome at this time consisted of house-churches; Phoebe was to deliver the letter first to Prisca and Aquila and their house-church; Prisca and Aquila were to convene an assembly of the whole Christian community, the first for some time, at which Romans was to be received and read; Prisca and Aquila were to be asked to arrange for copies of Romans to be made; Phoebe was to deliver these copies to other house-churches; and Phoebe was to read Romans in the way that Paul had coached her at each of the gatherings to which she took it. 1. Introduction It is the spring of AD 56 or 57, and Paul has just spent the winter in Corinth.1 Now he is on his way to Jerusalem with the collection (15:25- 1 For his spending the winter of 55–56 in Corinth, see C. E. B. Cranfield, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Epistle to the Romans (2 vols; ICC; Edinburgh: 196 TYNDALE BULLETIN 62.2 (2011) 322). -

Aqueduct Racetrack Is “The Big Race Place”

Table of Contents Chapter 1: Welcome to The New York Racing Association ......................................................3 Chapter 2: My NYRA by Richard Migliore ................................................................................6 Chapter 3: At Belmont Park, Nothing Matters but the Horse and the Test at Hand .............7 Chapter 4: The Belmont Stakes: Heartbeat of Racing, Heartbeat of New York ......................9 Chapter 5: Against the Odds, Saratoga Gets a Race Course for the Ages ............................11 Chapter 6: Day in the Life of a Jockey: Bill Hartack - 1964 ....................................................13 Chapter 7: Day in the Life of a Jockey: Taylor Rice - Today ...................................................14 Chapter 8: In The Travers Stakes, There is No “Typical” .........................................................15 Chapter 9: Our Culture: What Makes Us Special ....................................................................18 Chapter 10: Aqueduct Racetrack is “The Big Race Place” .........................................................20 Chapter 11: NYRA Goes to the Movies .......................................................................................22 Chapter 12: Building a Bright Future ..........................................................................................24 Contributors ................................................................................................................26 Chapter 1 Welcome to The New York Racing Association On a -

Governor Andrew M. Cuomo to Proclaim MEMORIALIZING June 5

Assembly Resolution No. 347 BY: M. of A. Solages MEMORIALIZING Governor Andrew M. Cuomo to proclaim June 5, 2021, as Belmont Stakes Day in the State of New York, and commending the New York Racing Association upon the occasion of the 152nd running of the Belmont Stakes WHEREAS, The Belmont Stakes is one of the most important sporting events in New York State; it is the conclusion of thoroughbred racing's prestigious three-contest Triple Crown; and WHEREAS, Preceded by the Kentucky Derby and Preakness Stakes, the Belmont Stakes is nicknamed the "Test of the Champion" due to its grueling mile and a half distance; and WHEREAS, The Triple Crown has only been completed 12 times; the 12 horses to accomplish this historic feat are: Sir Barton, 1919; Gallant Fox, 1930; Omaha, 1935; War Admiral, 1937; Whirlaway, 1941; Count Fleet, 1943; Assault, 1946; Citation, 1948; Secretariat, 1973; Seattle Slew, 1977; Affirmed, 1978; and American Pharoah, 2015; and WHEREAS, The Belmont Stakes has drawn some of the largest sporting event crowds in New York history, including 120,139 people for the 2004 running of the race; and WHEREAS, This historic event draws tens of thousands of horse racing fans annually to Belmont Park and generates millions of dollars for New York State's economy; and WHEREAS, The Belmont Stakes is shown to a national television audience of millions of people on network television; and WHEREAS, The Belmont Stakes is named after August Belmont I, a financier who made a fortune in banking in the middle to late 1800s; he also branched out -

Accepting Entries

FRIDAY, DECEMBER 11, 2020 ©2020 HORSEMAN PUBLISHING CO., LEXINGTON, KY USA • FOR ADVERTISING INFORMATION CALL (859) 276-4026 Ruthless Hanover Turns Heads With Big 1:48.4 Meadowlands Win ACCEPTING ENTRIES Last Saturday’s card at the Meadowlands was highlighted by two performances that turned heads, especially because for the hottest sale this winter of the strong head wind that horses faced as they reached the homestretch, and a wind chill temperature that felt like it was in the 30s. The conditions were so extreme that the judges gave a one-second time allowance. American History, who won last year’s Breeders Crown Open Pace, won the Meadowlands Preferred in 1:48.4, reeling off his third straight win at the Big M. He is back in to go this Saturday night at the Meadowlands in the $28,000 Preferred. American History’s effort last Saturday made the perform- February 9 & 10, 2021 ance turned in by the winner the race before him all the ENTER ONLINE AT more notable. Ruthless Hanover, a 3-year-old gelded son of Somebeachsomewhere, won a non-winners (of six or www.bloodedhorse.com $75,000, for 5 year olds and under and with other condi- Sale entries will close around mid-January, 2021. tions) event by an astounding 5 ¼ lengths in 1:48.4. It was the sophomore’s sixth career victory, which have all come this year because of an injury he sustained as a 2 year old. Going into the race, Ruthless Hanover had a record of 11- 5-2-2 and had won at the Meadowlands in 1:49.2 on Nov. -

WILL HE >JUSTIFY= the HYPE?

SATURDAY, APRIL 7, 2018 BLUE GRASS COULD BE WHITE OUT WILL HE >JUSTIFY= Assuming a potential snowstorm Friday night doesn=t put a THE HYPE? damper on things, a full field is set to go postward in Saturday=s GII Toyota Blue Grass S. The conversation about contenders must start with $1-million KEESEP yearling Good Magic (Curlin), who broke his maiden emphatically in the GI Breeders= Cup Juvenile at Del Mar en route to Eclipse Award honors. Heavily favored in the GII Xpressbet Fountain of Youth on seasonal debut at Gulfstream Mar. 3, he settled for a non-threatening third with no obvious excuse. Flameaway (Scat Daddy), second in the Mar. 10 GII Tampa Bay Derby behind expected scratch Quip (Distorted Humor) after annexing the GIII Sam F. Davis S. there in February, took a rained-off renewal of the GIII Bourbon S. in the Keeneland slop last October. Cont. p3 Justify | Benoit Photo IN TDN EUROPE TODAY ASTUTE AGENT HAS GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE >TDN Rising Star= Justify (Scat Daddy), almost certainly the Kelsey Riley sat down with Australia based Frenchman most highly regarded horse in the world to have not yet taken Louis Le Metayer to get his thoughts on various aspects of on stakes company, will get his class test on Saturday when he the Australian racing scene. Click or tap here to go straight faces the likes of MGISW Bolt d=Oro (Medaglia d=Oro) in the to TDN Europe. GI Santa Anita Derby. A 9 1/2-length jaw-dropping debut winner going seven panels here Feb. -

MJC Media Guide

2021 MEDIA GUIDE 2021 PIMLICO/LAUREL MEDIA GUIDE Table of Contents Staff Directory & Bios . 2-4 Maryland Jockey Club History . 5-22 2020 In Review . 23-27 Trainers . 28-54 Jockeys . 55-74 Graded Stakes Races . 75-92 Maryland Million . 91-92 Credits Racing Dates Editor LAUREL PARK . January 1 - March 21 David Joseph LAUREL PARK . April 8 - May 2 Phil Janack PIMLICO . May 6 - May 31 LAUREL PARK . .. June 4 - August 22 Contributors Clayton Beck LAUREL PARK . .. September 10 - December 31 Photographs Jim McCue Special Events Jim Duley BLACK-EYED SUSAN DAY . Friday, May 14, 2021 Matt Ryb PREAKNESS DAY . Saturday, May 15, 2021 (Cover photo) MARYLAND MILLION DAY . Saturday, October 23, 2021 Racing dates are subject to change . Media Relations Contacts 301-725-0400 Statistics and charts provided by Equibase and The Daily David Joseph, x5461 Racing Form . Copyright © 2017 Vice President of Communications/Media reproduced with permission of copyright owners . Dave Rodman, Track Announcer x5530 Keith Feustle, Handicapper x5541 Jim McCue, Track Photographer x5529 Mission Statement The Maryland Jockey Club is dedicated to presenting the great sport of Thoroughbred racing as the centerpiece of a high-quality entertainment experience providing fun and excitement in an inviting and friendly atmosphere for people of all ages . 1 THE MARYLAND JOCKEY CLUB Laurel Racing Assoc. Inc. • P.O. Box 130 •Laurel, Maryland 20725 301-725-0400 • www.laurelpark.com EXECUTIVE OFFICIALS STATE OF MARYLAND Sal Sinatra President and General Manager Lawrence J. Hogan, Jr., Governor Douglas J. Illig Senior Vice President and Chief Financial Officer Tim Luzius Senior Vice President and Assistant General Manager Boyd K. -

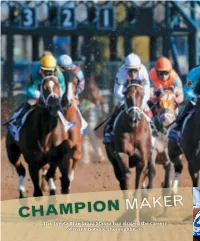

Champion Maker

MAKER CHAMPION The Toyota Blue Grass Stakes has shaped the careers of many notable Thoroughbreds 48 SPRING 2016 K KEENELAND.COM Below, the field breaks for the 2015 Toyota Blue Grass Stakes; bottom, Street Sense (center) loses a close 2007 running. MAKER Caption for photo goes here CHAMPION KEENELAND.COM K SPRING 2016 49 RICK SAMUELS (BREAK), ANNE M. EBERHARDT CHAMPION MAKER 1979 TOBY MILT Spectacular Bid dominated in the 1979 Blue Grass Stakes before taking the Kentucky Derby and Preakness Stakes. By Jennie Rees arl Nafzger’s short list of races he most send the Keeneland yearling sales into the stratosphere. But to passionately wanted to win during his Hall show the depth of the Blue Grass, consider the dozen 3-year- of Fame training career included Keeneland’s olds that lost the Blue Grass before wearing the roses: Nafzger’s Toyota Blue Grass Stakes. two champions are joined by the likes of 1941 Triple Crown C winner Whirlaway and former record-money earner Alysheba Instead, with his active trainer days winding down, he has had to (disqualified from first to third in the 1987 Blue Grass). settle for a pair of Kentucky Derby victories launched by the Toyota Then there are the Blue Grass winners that were tripped Blue Grass. Three weeks before they entrenched their names in his- up in the Derby for their legendary owners but are ensconced tory at Churchill Downs, Unbridled finished third in the 1990 Derby in racing lore and as stallions, including Calumet Farm’s Bull prep race, and in 2007 Street Sense lost it by a nose. -

Kentucky Derby, Flamingo Stakes, Florida Derby, Blue Grass Stakes, Preakness, Queen’S Plate 3RD Belmont Stakes

Northern Dancer 90th May 2, 1964 THE WINNER’S PEDIGREE AND CAREER HIGHLIGHTS Pharos Nearco Nogara Nearctic *Lady Angela Hyperion NORTHERN DANCER Sister Sarah Polynesian Bay Colt Native Dancer Geisha Natalma Almahmoud *Mahmoud Arbitrator YEAR AGE STS. 1ST 2ND 3RD EARNINGS 1963 2 9 7 2 0 $ 90,635 1964 3 9 7 0 2 $490,012 TOTALS 18 14 2 2 $580,647 At 2 Years WON Summer Stakes, Coronation Futurity, Carleton Stakes, Remsen Stakes 2ND Vandal Stakes, Cup and Saucer Stakes At 3 Years WON Kentucky Derby, Flamingo Stakes, Florida Derby, Blue Grass Stakes, Preakness, Queen’s Plate 3RD Belmont Stakes Horse Eq. Wt. PP 1/4 1/2 3/4 MILE STR. FIN. Jockey Owner Odds To $1 Northern Dancer b 126 7 7 2-1/2 6 hd 6 2 1 hd 1 2 1 nk W. Hartack Windfields Farm 3.40 Hill Rise 126 11 6 1-1/2 7 2-1/2 8 hd 4 hd 2 1-1/2 2 3-1/4 W. Shoemaker El Peco Ranch 1.40 The Scoundrel b 126 6 3 1/2 4 hd 3 1 2 1 3 2 3 no M. Ycaza R. C. Ellsworth 6.00 Roman Brother 126 12 9 2 9 1/2 9 2 6 2 4 1/2 4 nk W. Chambers Harbor View Farm 30.60 Quadrangle b 126 2 5 1 5 1-1/2 4 hd 5 1-1/2 5 1 5 3 R. Ussery Rokeby Stables 5.30 Mr. Brick 126 1 2 3 1 1/2 1 1/2 3 1 6 3 6 3/4 I. -

Visual Foxpro

Taylor Made Sales Agency, Inc. pedigree by CompuSire NEARCTIC NORTHERN DANCER NATALMA STORM BIRD (Q) NEW PROVIDENCE SOUTH OCEAN SHINING SUN STORM CAT (Q) BOLD RULER SECRETARIAT SOMETHINGROYAL TERLINGUA CRIMSON SATAN CRIMSON SAINT BOLERO ROSE GIANT'S CAUSEWAY (C) RED GOD BLUSHING GROOM RUNAWAY BRIDE RAHY (Q) HALO GLORIOUS SONG BALLADE MARIAH'S STORM HAIL TO REASON ROBERTO BRAMALEA IMMENSE CHIEFTAIN IMSODEAR 5 IRONICALLY NOT THIS TIME FORTY NINER MR. PROSPECTOR FILE END SWEEP DANCE SPELL BROOM DANCE WITCHING HOUR TRIPPI VALID APPEAL IN REALITY DESERT TRIAL JEALOUS APPEAL COUGAR II JEALOUS CAT ONLY THE LOYAL MISS MACY SUE ROUGH'N TUMBLE MINNESOTA MAC COW GIRL II 1 GREAT ABOVE INTENTIONALLY 3 TA WEE ASPIDISTRA YADA YADA SWORD DANCER DAMASCUS KERALA STEM SECRETARIAT 1 TWEAK 3 TA WEE STORM BIRD NORTHERN DANCER SOUTH OCEAN 1- 1- 8- 0- 0 STORM CAT (Q) TERLINGUA SECRETARIAT DP: 10 CRIMSON SAINT QP: 12 FORESTRY HIS MAJESTY PLEASANT COLONY TP: 22 SUN COLONY SHARED INTEREST QR: Q5 DR. FAGER SURGERY 3 DI: 1.50 BOLD SEQUENCE CD: 0.30 DISCREET CAT SWORD DANCER DAMASCUS KERALA Sibling Codes: PRIVATE ACCOUNT (Q) BUCKPASSER Same dam only = odd NUMBERED ACCOUNT INTRIGUING Same dam & sire = even PRETTY DISCREET BELIEVE IT IN REALITY BREAKFAST BELL PRETTY PERSUASIVE TOM ROLFE BURY THE HATCHET 5 CHRISTMAS WISHES LADY GLAMOUR FAPPIANO MR. PROSPECTOR KILLALOE UNBRIDLED (B/I) LE FABULEUX GANA FACIL CHAREDI BROKEN VOW NIJINSKY II NORTHERN DANCER FLAMING PAGE WEDDING VOW WEDDING PICTURE BLUSHING GROOM STRIKE A POSE REPETA NUREYEV NORTHERN DANCER STORM CAT - 3m x 4m SPECIAL NORTHERN DANCER - 5m x 6m, 6m, 6m ATTICUS ATHYKA SECRETARIAT SECRETARIAT - 5f, 6f x 6f, 6f, 6f PRINCESSE KATHY BLUSHING GROOM - 5m x 6f ATTICO SEATTLE SLEW CAPOTE DAMASCUS - 5f x 5m TOO BALD TA WEE - 5m, 6f x IRISH COCO I'M PRETTY SECRETARIAT IN REALITY - 6m x 6m 3 QUIT ME NOT MR.