UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Dreyfus' Frame Problem Argument Cannot Justify Anti

Why Dreyfus’ Frame Problem Argument Cannot Justify Anti- Representational AI Nancy Salay ([email protected]) Department of Philosophy, Watson Hall 309 Queen‘s University, Kingston, ON K7L 3N6 Abstract disembodied cognitive models will not work, and this Hubert Dreyfus has argued recently that the frame problem, conclusion needs to be heard. By disentangling the ideas of discussion of which has fallen out of favour in the AI embodiment and representation, at least with respect to community, is still a deal breaker for the majority of AI Dreyfus‘ frame problem argument, the real locus of the projects, despite the fact that the logical version of it has been general polemic between traditional computational- solved. (Shanahan 1997, Thielscher 1998). Dreyfus thinks representational cognitive science and the more recent that the frame problem will disappear only once we abandon the Cartesian foundations from which it stems and adopt, embodied approaches is revealed. From this, I hope that instead, a thoroughly Heideggerian model of cognition, in productive debate will ensue. particular one that does not appeal to representations. I argue The paper proceeds in the following way: in section I, I that Dreyfus is too hasty in his condemnation of all describe and distinguish the logical version of the frame representational views; the argument he provides licenses problem and the philosophical one that remains unsolved; in only a rejection of disembodied models of cognition. In casting his net too broadly, Dreyfus circumscribes the section II, I rehearse Dreyfus‘ negative argument, what I‘ll cognitive playing field so closely that one is left wondering be calling his frame problem argument; in section III, I how his Heideggerian alternative could ever provide a highlight some key points from Dreyfus‘ positive account of foundation explanatorily robust enough for a theory of a Heideggerian alternative; in section IV, I make my case cognition. -

Kierkegaard on Selfhood and Our Need for Others

Kierkegaard on Selfhood and Our Need for Others 1. Kierkegaard in a Secular Age Scholars have devoted much attention lately to Kierkegaard’s views on personal identity and, in particular, to his account of selfhood.1 Central to this account is the idea that a self is not something we automatically are. It is rather something we must become. Thus, selfhood is a goal to realize or a project to undertake.2 To put the point another way, while we may already be selves in some sense, we have to work to become real, true, or “authentic” selves.3 The idea that authentic selfhood is a project is not unique to Kierkegaard. It is common fare in modern philosophy. Yet Kierkegaard distances himself from popular ways of thinking about the matter. He denies the view inherited from Rousseau that we can discover our true selves by consulting our innermost feelings, beliefs, and desires. He also rejects the idea developed by the German Romantics that we can invent our true selves in a burst of artistic or poetic creativity. In fact, according to Kierkegaard, becom- ing an authentic self is not something we can do on our own. If we are to succeed at the project, we must look beyond ourselves for assistance. In particular, Kierkegaard thinks, we must rely on God. For God alone can provide us with the content of our real identi- ties.4 A longstanding concern about Kierkegaard arises at this point. His account of au- thentic selfhood, like his accounts of so many concepts, is religious. -

Man As 'Aggregate of Data'

AI & SOCIETY https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-018-0852-6 OPEN FORUM Man as ‘aggregate of data’ What computers shouldn’t do Sjoukje van der Meulen1 · Max Bruinsma2 Received: 4 October 2017 / Accepted: 10 June 2018 © The Author(s) 2018 Abstract Since the emergence of the innovative field of artificial intelligence (AI) in the 1960s, the late Hubert Dreyfus insisted on the ontological distinction between man and machine, human and artificial intelligence. In the different editions of his clas- sic and influential book What computers can’t do (1972), he posits that an algorithmic machine can never fully simulate the complex functioning of the human mind—not now, nor in the future. Dreyfus’ categorical distinctions between man and machine are still relevant today, but their relation has become more complex in our increasingly data-driven society. We, humans, are continuously immersed within a technological universe, while at the same time ubiquitous computing, in the words of computer scientist Mark Weiser, “forces computers to live out here in the world with people” (De Souza e Silva in Interfaces of hybrid spaces. In: Kavoori AP, Arceneaux N (eds) The cell phone reader. Peter Lang Publishing, New York, 2006, p 20). Dreyfus’ ideas are therefore challenged by thinkers such as Weiser, Kevin Kelly, Bruno Latour, Philip Agre, and Peter Paul Verbeek, who all argue that humans are much more intrinsically linked to machines than the original dichotomy suggests—they have evolved in concert. Through a discussion of the classical concepts of individuum and ‘authenticity’ within Western civilization, this paper argues that within the ever-expanding data-sphere of the twenty-first century, a new concept of man as ‘aggregate of data’ has emerged, which further erodes and undermines the categorical distinction between man and machine. -

Creativity in Nietzsche and Heidegger: the Relation of Art and Artist

Creativity in Nietzsche and Heidegger: The Relation of Art and Artist Justin Hauver Philosophy and German Mentor: Hans Sluga, Philosophy August 22, 2011 I began my research this summer with a simple goal in mind: I wanted to out- line the ways in which the thoughts of Friedrich Nietzsche and Martin Heidegger complement one another with respect to art. I had taken a few courses on each philosopher beforehand, so I had some inclination as to how their works might be brought into agreement. However, I almost immediately ran into difficulty. It turns out that Heidegger, who lived and thought two or three generations after Nietzsche, had actually lectured on the topic of Nietzsche's philosophy of art and had placed Nietzsche firmly in a long tradition characterized by its mis- understanding of art and of the work of art. This means that Heidegger himself did not agree with me|he did not see his thoughts on art as complementary with Nietzsche's. Rather, Heidegger saw his work as an improvement over the misguided aesthetic tradition. Fortunately for me, Heidegger was simply mistaken. At least, that's my thesis. Heidegger did not see his affinity with Nietzsche because he was misled by his own misinterpretation. Nevertheless, his thoughts on art balance nicely with those of Nietzsche. To support this claim, I will make three moves today. First, I will set up Heidegger's critique, which is really a challenge to the entire tradition that begins with Plato and runs its course up to Nietzsche. Next, I will turn to Heidegger's views on art to see how he overcomes the tradition and answers his own criticism of aesthetics. -

The Routledge Handbook of Embodied Cognition

THE ROUTLEDGE HANDBOOK OF EMBODIED COGNITION Embodied cognition is one of the foremost areas of study and research in philosophy of mind, philosophy of psychology and cognitive science. The Routledge Handbook of Embodied Cognition is an outstanding guide and reference source to the key philosophers, topics and debates in this exciting subject and essential reading for any student and scholar of philosophy of mind and cognitive science. Comprising over thirty chapters by a team of international contributors, the Handbook is divided into six parts: Historical underpinnings Perspectives on embodied cognition Applied embodied cognition: perception, language, and reasoning Applied embodied cognition: social and moral cognition and emotion Applied embodied cognition: memory, attention, and group cognition Meta-topics. The early chapters of the Handbook cover empirical and philosophical foundations of embodied cognition, focusing on Gibsonian and phenomenological approaches. Subsequent chapters cover additional, important themes common to work in embodied cognition, including embedded, extended and enactive cognition as well as chapters on embodied cognition and empirical research in perception, language, reasoning, social and moral cognition, emotion, consciousness, memory, and learning and development. Lawrence Shapiro is a professor in the Department of Philosophy, University of Wisconsin – Madison, USA. He has authored many articles spanning the range of philosophy of psychology. His most recent book, Embodied Cognition (Routledge, 2011), won the American Philosophical Association’s Joseph B. Gittler award in 2013. Routledge Handbooks in Philosophy Routledge Handbooks in Philosophy are state-of-the-art surveys of emerging, newly refreshed, and important fields in philosophy, providing accessible yet thorough assessments of key problems, themes, thinkers, and recent developments in research. -

On the Internet, Second Edition

Copyrighted Material-Taylor & Francis Copyrighted Material-Taylor & Francis On the Internet Second edition Copyrighted Material-Taylor & Francis Thinking In Action Series editors: Simon Critchley, New School University, New York, and Richard Kearney, Uni- versity Gollege Dublin and Boston College Thinking in Action is a major new series that takes philosophy to its public. Each book in the series is written by a major international philosopher or thinker, engages with an important contemporary topic, and is clearly and accessibly written. The series informs and sharpens debate on issues as wide ranging as the Internet, religion, the problem of immigration and refugees, and the way we think about science. Punchy, short and stimulating, Thinking in Action is an indispensable starting point for anyone who wants to think seriously about major issues confront- ing us today. Praise for the series ‘. allows a space for distinguished thinkers to write about their passions.’ The Philosophers’ Magazine ‘. deserve high praise.’ Boyd Tonkin, The Independent (UK) ‘This is clearly an important series. I look forward to reading future volumes.’ Frank Kermode, author of Shakespeare’s Language ‘. both rigorous and accessible.’ Humanist News ‘. the series looks superb.’ Quentin Skinner ‘. an excellent and beautiful series.’ Ben Rogers, author of A.J. Ayer: A Life ‘Routledge’s Thinking in Action series is the theory junkie’s answer to the eminently pocketable Penguin 60s series.’ Mute Magazine (UK) ‘Routledge’s new series, Thinking in Action, brings philosophers to our aid...’ The Evening Standard (UK) ‘...a welcome new series by Routledge.’ Bulletin of Science, Technology and Society (Can) ‘Routledge’s innovative new Thinking in Action series takes the concept of philosophy a step further’ The Bookwatch Copyrighted Material-Taylor & Francis HUBERT L. -

Mood-Consciousness and Architecture

Mood-Consciousness and Architecture Mood-Consciousness and Architecture: A Phenomenological Investigation of Therme Vals by way of Martin Heidegger’s Interpretation of Mood A Thesis submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER of SCIENCE in ARCHITECTURE In the School of Architecture and Interior Design of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning 2011 by Afsaneh Ardehali Master of Architecture, California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo, CA 1987 Committee Members: John E. Hancock (Chair) Nnamdi Elleh, Ph.D. Mood-Consciousness and Architecture abstract This thesis is an effort to unfold the disclosing power of mood as the basic character of all experiencing as well as theorizing in architecture. Having been confronted with the limiting ways of the scientific approach to understanding used in the traditional theoretical investigations, (according to which architecture is understood as a mere static object of shelter or aesthetic beauty) we turn to Martin Heidegger’s existential analysis of the meaning of Being and his new interpretation of human emotions. Translations of philosophers Eugene Gendlin, Richard Polt, and Hubert Dreyfus elucidate the deep meaning of Heidegger’s investigations and his approach to understanding mood. In contrast to our customary beliefs, which are largely informed by scientific understanding of being and emotions, this new understanding of mood clarifies our experience of architecture by shedding light on the contextualizing character of mood. In this expanded horizon of experiencing architecture, the full potentiality of mood in our experience of architecture becomes apparent in resoluteness of our new Mood-Consciousness of architecture. -

GROUP COGNITION Pin 805 (8:22:39 PM): Concur* GROUP COGNITION Information Science and Technology, Drexel University

v (8: : 6 ): O ay, t we s ou d Sup (8:22:17 PM): ok Avr (8:22:28 PM): A = 1/2bh Avr (8:22:31 PM): I believe pin 805 (8:22:35 PM): yes pin 805 (8:22:37 PM): i concue Gerry Stahl is Associate Professor in the College of COGNITION GROUP pin 805 (8:22:39 PM): concur* GROUP COGNITION Information Science and Technology, Drexel University. Avr (8:22:42 PM): then find the area of Computer Support for Building He is founding coeditor of the International Journal of > Avr (8:22:54 PM): oh, wait Collaborative Knowledge Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning. computer science Sup (8:23:03 PM): the base and height are Gerry Stahl Avr (8:23:11 PM): no > Innovative uses of global and local networks of linked “In this bold and brilliant book, Stahl integrates three distinct fields of knowledge: computa- computers make new ways of collaborative working, tional design, communication studies, and the learning sciences. Such an interdisciplinary learning, and acting possible. In Group Cognition Gerry effort is both timely and necessary to foster innovations for human learning. This book shows Stahl explores the technological and social reconfigura- how small-group cognition can be the underlying building block for individual and collective GROUP COGNITION tions that are needed to achieve computer-supported knowledge building.” collaborative knowledge building—group cognition that —Sten Ludvigsen, Professor and Director of InterMedia, University of Oslo Computer Support for Building Collaborative Knowledge transcends the limits of individual cognition. Computers can provide active media for social group cognition “This book, which synthesizes research by a leading thinker in computer-supported collabo- where ideas grow through the interactions within groups rative learning, offers a thought-provoking and challenging thesis on the relationship of people; software functionality can manage group between collaboration, technology mediation, and learning. -

Read an Excerpt

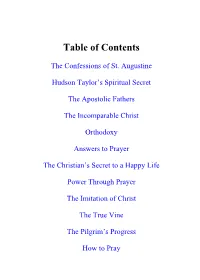

Table of Contents The Confessions of St. Augustine Hudson Taylor’s Spiritual Secret The Apostolic Fathers The Incomparable Christ Orthodoxy Answers to Prayer The Christian’s Secret to a Happy Life Power Through Prayer The Imitation of Christ The True Vine The Pilgrim’s Progress How to Pray All of Grace Born Crucified Holiness (Abridged) The Overcoming Life The Secret of Guidance Names of God Prevailing Prayer St. Augustine (Books One to Ten) GENERAL EDITOR ROSALIE De ROSSET MOODY CLASSICS MOODY PUBLISHERS CHICAGO CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 9 THE FIRST BOOK ...................................................................... 19 Confessions of the greatness and unsearchableness of God—Of God’s mercies in infancy and boyhood, and human willfulness—Of his own sins of idleness, abuse of his studies, and of God’s gifts up to his fifteenth year. THE SECOND BOOK ................................................................. 44 Object of these confessions—Further ills of idleness developed in his sixteenth year—Evils of ill society, which betrayed him into theft. THE THIRD BOOK .................................................................... 58 His residence at Carthage from his seventeenth to his nineteenth year—Source of his disorders—Love of shows—Advance in studies, and love of wisdom— Distaste for Scripture—Led astray to the Manichaeans— Refutation of some of their tenets—Grief of his mother, Monnica, at his heresy, and prayers for his conversion— Her vision from God, and answer through a Bishop. THE FIRST BOOK CONFESSION OF THE GREATNESS AND UNSEARCHABLENESS OF GOD, OF GOD’S MERCIES IN INFANCY AND BOYHOOD, AND HUMAN WILFULNESS; OF HIS OWN SINS OF IDLENESS, ABUSE OF HIS STUDIES, AND OF GOD’S GIFTS UP TO HIS FIFTEENTH YEAR. -

Sincere Faith: an Exposition of the Book of James Sermon One: a Sincere Introduction May 16, 2021

Sincere Faith: An Exposition of the Book of James Sermon One: A Sincere Introduction May 16, 2021 Opening ILL: Sometimes things just don’t pass the sniff test. Let me ask you this: Imagine you grab a gallon of milk from the fridge, you open it up and it just doesn’t smell right. Do you look at the expiration date and say, (1)“Well, this says I have 3 more days.” Or, (2) do you say, “I don’t care what that date says, it just doesn’t smell right, or (3) do you ask your spouse, “Honey? Does this smell ok to you?” See, sometimes it’s not that things are rotten, they’re just a little off. Quote: “It is vain to shut our eyes to the fact that there is a vast quantity of so-called Christianity nowadays which you cannot declare positively unsound, but which, nonetheless, is not full measure, good weight and sixteen ounces to the pound. It is a Christianity in which there is undeniably something about Christ, something of grace, something about faith, and something about repentance and something about holiness; but it is not the real thing as it is in the Bible.” J. C. Ryle, “Holiness”, page 13 I. A Sincere Introduction to the Book of James Point: We have to be careful here not to get too bogged down in the details. While I love a good, academic discussion as much as the next guy, I will pass lightly over these things. After all, why spend 40 minutes convincing you that James wrote the book of James? A. -

From Cognitive Science to Social Epistemology David Alexander Eck University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 3-12-2015 The ncE ultured Mind: From Cognitive Science to Social Epistemology David Alexander Eck University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Philosophy Commons Scholar Commons Citation Eck, David Alexander, "The ncE ultured Mind: From Cognitive Science to Social Epistemology" (2015). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/5472 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Encultured Mind: From Cognitive Science to Social Epistemology by David Eck A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Philosophy College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Co-Major Professor: Alexander Levine, Ph.D. Co-Major Professor: Stephen Turner, Ph.D. Charles Guignon, Ph.D. Joanne Waugh, Ph.D. William Goodwin, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 12, 2015 Keywords: enactivism, participatory sense-making, embodied knowledge, tacit knowledge, testimonial knowledge Copyright © 2015, David Eck Dedication To Lauren, whose understanding and support lie quietly between the lines of the many pages that follow. Acknowledgments It is hard to imagine the existence of the following project—never mind its completion—without the singular help of Alex Levine. His scholarship is as remarkable as it is unassuming, only surpassed by his concern for others and readiness to help. -

Kierkegaard and the Funny by Eric Linus Kaplan a Dissertation

Kierkegaard and the Funny By Eric Linus Kaplan A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Philosophy in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Alva Noë, co-chair Professor Hubert Dreyfus, co-chair Professor Sean D. Kelly Professor Deniz Göktürk Summer 2017 Abstract Kierkegaard and the Funny by Eric Linus Kaplan Doctor of Philosophy in Philosophy University of California, Berkeley Professor Alva Noë, co-chair Professor Hubert Dreyfus, co-chair This dissertation begins by addressing a puzzle that arises in academic analytic interpretations of Kierkegaard’s Concluding Unscientific Postscript. The puzzle arises when commentators try to paraphrase the book’s philosophical thesis “truth is subjectivity.” I resolve this puzzle by arguing that the motto “truth is subjectivity” is like a joke, and resists and invites paraphrase just as a joke does. The connection between joking and Kierkegaard’s philosophical practice is then deepened by giving a philosophical reconstruction of Kierkegaard's definition of joking as a way of responding to contradiction that is painless precisely because it sees the way out in mind. Kierkegaard’s account of joking and his account of his own philosophical project are used to mutually illuminate each other. The dissertation develops a phenomenology of retroactive temporality that explains how joking and subjective thinking work. I put forward an argument for why “existential humorism” is a valuable approach to life for Kierkegaard, but why it ultimately fails, and explain the relationship between comedy as a way of life and faith as a way of life, particularly as they both relate to risk.