The Orient at Leicester Square: Virtual Visual Encounters in the First Panoramas Hélène Ibata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trades' Directory. 811

1841.] TRADES' DIRECTORY. 811 SILK &VEL YET MANFRS.-continued. l\Iay William, 132 Bishops~ate without DentJ.30,31,32 Crawfordst.Portmansq Brandon William, 23 Spital square *Nalders, Spall & Co. 41 Cheapside Devy M. 73 Lower Grosvenor street, & Bridges & Camp bell, 19 Friday street N eill & Langlands, 45 Friday street 120 George street, Edinburgh Bridgett Joseph & Co.63 Alderman bury Perry T. W. & Co. 20 Steward st. Spitalfi *Donnon Wm.3.5Garden row, London rd British, IJ-ish, ~· Colonial Silk Go. 10~ Place & Wood, 10 Cateaton street Duthoit & Harris, 77 Bishopsgate within King's arms yard Powell John & Daniel, 1 Milk !'treet t Edgington \Yilliam, 37 Piccadilly Brocklehurst Jno. & Th. 32 & 331\-Iilk st t Price T. Divett, 19 Wilson st. Finsbury Elliot Miss Margt. Anne, 43 Pall mall Brooks Nathaniel, 25 Spital square Ratliffs & Co. 78\Vood st. Cheapside E~·les,Evans,Hands&.Wells,5Ludgatest Brown .Archbd. & Co.ltl Friday st.Chpsi Rawlinson Geo. & Co. 34 King st. City *Garnham Wm. Henry, 30 Red Lion sq *Brown James U. & Co. 3,5 Wood street Reid John & Co. 21 Spital square George & Lambert, 192 Regent street *Brunskill Chas.& Wm.5 Paternostr.rw Relph & Witham, 6 Mitre court, Milk st Green Saml. 7 Lit. Aygyll st.llegent st Brunt Josiah, & Co.12 Milk st. Cheapsi Remington, Mills & Co. 30 Milk street Griffiths & Crick, 1 Chandos street Bullock Wm. & Co. 11 Paternoster row tRobinsonJas.&Wm.3&4Milkst.Chepsid +Hall Hichanl, 29 St. John street Buttre~s J. J. & Son, 36Stewardst.Spital RobinsonJ. & T. 21 to 23 Fort st. Spitalfi *Hamer & Jones, 59 Blackfriars road Buttress John, 15 Spital square Salter J. -

HOLBA-Insights-Report-Jul-20.Pdf

HEART OF LONDON JULY AREA PERFORMANCE HEART OF LONDON AREA PERFORMANCE CONTENTS JULY 2020 EDITION INTRODUCTION 02 Welcome to our area performance report. This monthly summary provides trends in footfall, spending SUMMARY ANALYSIS 03 and much more, in the Heart of London area. Focusing on Leicester Square, Piccadilly Circus, Haymarket, Piccadilly and FOOTFALL TRENDS 04 St James’s, find out exactly how our area has performed FOOTFALL OVERVIEW 05 throughout the month. HOURLY FOOTFALL 06 The report is available exclusively to members, and explores REGIONAL FOOTFALL 07 changes in trends that impact the performance of our area, allowing your business to plan with confidence and make the COVID-19 AND FOOTFALL 08 most of being in the heart of London. YOUR FEEDBACK IS IMPORTANT TO US PROPERTY & INVESTMENT 09 PLEASE CLICK ON THE BUTTON INVESTMENT 10 TO REQUEST NEW DATA OR ANALYSIS PROPERTY PERFORMANCE 11 LEASE AVAILABILITY 12 EVENTS & ACTIVITY 13 IMPACT CALENDAR 14 GLOSSARY 15 See our Glossary for more detail on data sources and definitions. 2 HEART OF LONDON AREA PERFORMANCE SUMMARY ANALYSIS – JULY 2020 Rainfall (mm) 2020 2019 500K 25 YEAR ON YEAR FOOTFALL 450K -72% Footfall in the current month compared to the same month last year 400K 20 350K 300K 15 MONTH ON MONTH FOOTFALL 250K +97% Footfall in the current month compared Footfall 200K 10 to the previous month Rainfall (mm) Rainfall 150K 100K 5 YEAR TO DATE FOOTFALL 50K -58% Footfall in the current year to date K 0 compared to the same period last year M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 1 2 Week 28 Week 29 Week 30 Week 31 July trend summary • Like-for-like footfall in the Heart of London area was down 72% in July 2020 compared to the same month last year. -

Timeline: 2-14 Baker Street Date Event Notes

Timeline: 2-14 Baker Street Parties: British Land, McAleer & Rushe. Bank of Ireland, NAMA, Portman Estate Topic: 2-14 Baker Street - in London which was subject to a loan from Bank of Ireland Timeline: Date Event Notes August Several media articles report on This was the second reported purchase by and agreement between British Land and McAleer & Rushe from British Land – the September McAleer & Rushe for the sale (by BL) previous deal was for the Swiss Centre in 2005 of 2-14 Baker Street. Leicester Square. Guide price for the 2-14 Baker Street property was UK£47.5m with British Land offering it as a potential 150,000 sq. ft development opportunity. 5th 2-14 Baker Street purchased by Travers Smith acted for McAleer & Rushe October McAleer & Rushe by British Land for Group on the acquisition. 2005 UK£57.2m. The existing building tenants: Purchase funded with a Bank of Offices let on a lease expiring in December Ireland loan. 2009. Retail accommodation let under four separate leases all expiring by December 2009 The property comprised 94,000 sq. ft. held on a 98 year headlease from the Portman Estate. 16th Planning Application submitted to Planning application filed by Gerald Eve, December Westminster City Council listing Chartered Surveyors and Property Consultants 2008 Owners pf 2-14 Baker Street as: Contact person: James Owens 1. Portman Estate (freeholder) [email protected] 2. Mourant & Co Trustees Ltd and Mourant Property Trustees Ltd Baker Street Unit Trust is owned by McAleer & as Trustees of the Baker Street Rushe with a Jersey address. -

COMMERCIAL DIRECTORY. Albrecht Henry Jas. & Co. East India

292 COMMERCIAL DIRECTORY. [1841. Albrecht Henry Jas. & Co. east india merchts. 14 Eastcheap Alexander Wm. Southwm·k Arms P.H. 151 Tooley street AlbrecLt John, colonial broker, 48 Fenchurch street Alexander Wm. John, barrister, 3 King's bench walk,Templtt Albri~ht Eliz. (1\Ira.),stationer, 36 Bridge ho. pl. N ewing.cau Alexanure Auguste, for. booksel. 37 Gt. Russell st. Bloomsb Alcock Anthony,glass & chinaman, 6 Charles st. Westminster Alexandre Edme, artificial florist, 20 King's rd. Bedford row Alcock Edward, grocer, 361 Rotherhithe Aley James, Fathe1· Red Cap P.H. Camberwell green Alcock John, rag merchant, 12 Addle hill, Doctors' Commons Aley Thomas, watchmaker, 18 Park side, Knight~bridge Alcock Wm. printers' joiner, 2! White Lion st. N orton folgate Aley William, poulterer, 2 Queen's buildings, Knights bridge Alcock Rutherford, physician, 13 Park place, St. James's Altord Charles, lighterman, 12 Bennett's hill, Due. corn. Alder Edward, coffee rooms, 208 Sloane st. Knightsbridge Alford, Fitzherbert & Co. cloth factors, 10 Ironmonger lane Alder John, Golden Horse P. H. Glasshouse yd. Aldersgt. st AI ford J ames, cooper& oil bag ma. 8 Bennett's hill, Doe. corn. Alderman Wm.Hen.Lm·dNelsonP.H.ll!Bishopsgt.without Alford Jenkins, Colonel lVardle P.H. 138 Tooley street Alders Jas. engraver & chaser, 3 Thorney st. Bloomsbury sq Alford Robert,engraver, & copperplate, letterpress & gold Aldersey Joseph Stephens, attomey, 8 Gower st. Bedford sq printer, 13 Bridge street, Southwark Aldersey Richard Baker, who. stationer, 11 Cloaklane1 City Altord Thomas,coachmaker,Cumber land st. N ewingtonbutts Alderson Geo. D. & Co. lead mercs. 2 Blenl1eim st. -

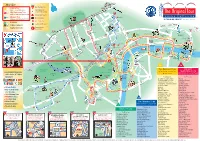

A4 Web Map 26-1-12:Layout 1

King’s Cross Start St Pancras MAP KEY Eurostar Main Starting Point Euston Original Tour 1 St Pancras T1 English commentary/live guides Interchange Point City Sightseeing Tour (colour denotes route) Start T2 W o Language commentaries plus Kids Club REGENT’S PARK Euston Rd b 3 u Underground Station r n P Madame Tussauds l Museum Tour Russell Sq TM T4 Main Line Station Gower St Language commentaries plus Kids Club q l S “A TOUR DE FORCE!” The Times, London To t el ★ River Cruise Piers ss Gt Portland St tenham Ct Rd Ru Baker St T3 Loop Line Gt Portland St B S s e o Liverpool St Location of Attraction Marylebone Rd P re M d u ark C o fo t Telecom n r h Stansted Station Connector t d a T5 Portla a m Museum Tower g P Express u l p of London e to S Aldgate East Original London t n e nd Pl t Capital Connector R London Wall ga T6 t o Holborn s Visitor Centre S w p i o Aldgate Marylebone High St British h Ho t l is und S Museum el Bank of sdi igh s B tch H Gloucester Pl s England te Baker St u ga Marylebone Broadcasting House R St Holborn ld d t ford A R a Ox e re New K n i Royal Courts St Paul’s Cathedral n o G g of Justice b Mansion House Swiss RE Tower s e w l Tottenham (The Gherkin) y a Court Rd M r y a Lud gat i St St e H n M d t ill r e o xfo Fle Fenchurch St Monument r ld O i C e O C an n s Jam h on St Tower Hill t h Blackfriars S a r d es St i e Oxford Circus n Aldwyc Temple l a s Edgware Rd Tower Hil g r n Reg Paddington P d ve s St The Monument me G A ha per T y Covent Garden Start x St ent Up r e d t r Hamleys u C en s fo N km Norfolk -

Waterloo in Myth and Memory: the Battles of Waterloo 1815-1915 Timothy Fitzpatrick

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2013 Waterloo in Myth and Memory: The Battles of Waterloo 1815-1915 Timothy Fitzpatrick Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES WATERLOO IN MYTH AND MEMORY: THE BATTLES OF WATERLOO 1815-1915 By TIMOTHY FITZPATRICK A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2013 Timothy Fitzpatrick defended this dissertation on November 6, 2013. The members of the supervisory committee were: Rafe Blaufarb Professor Directing Dissertation Amiée Boutin University Representative James P. Jones Committee Member Michael Creswell Committee Member Jonathan Grant Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For my Family iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Drs. Rafe Blaufarb, Aimée Boutin, Michael Creswell, Jonathan Grant and James P. Jones for being on my committee. They have been wonderful mentors during my time at Florida State University. I would also like to thank Dr. Donald Howard for bringing me to FSU. Without Dr. Blaufarb’s and Dr. Horward’s help this project would not have been possible. Dr. Ben Wieder supported my research through various scholarships and grants. I would like to thank The Institute on Napoleon and French Revolution professors, students and alumni for our discussions, interaction and support of this project. -

Aldwych-House-Brochure.Pdf

Executive summary • An iconic flagship in the heart of Midtown • This imposing building invested with period grandeur, has been brought to life in an exciting and modern manner • A powerful and dramatic entrance hall with 9 storey atrium creates a backdrop to this efficient and modern office • A total of 142,696 sq ft of new lettings have taken place leaving just 31,164 sq ft available • A space to dwell… 4,209 – 31,164 SQ FT 4 | ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM | 5 Aldwych House • MoreySmith designed reception • Full height (9 storey) central atrium fusing a modern which provides a light, modern, interior with imposing spacious circulation area 1920s architecture • Floors are served by a newly refurbished lightwell on the west side and a dramatically lit internal Aldwych House totals 174,000 atrium to the east from lower sq ft over lower ground to 8th ground to 3rd floor floors with a 65m frontage • An extensive timber roof terrace onto historic Aldwych around a glazed roof area • Showers, cycle storage and a drying room are located in the basement with easy access from the rear of the building • The ROKA restaurant is on the ground floor 6 | ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM | 7 8 | ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM Floorplate Typical upper floor c. 18,000 sq ft Typical upper floor CGI with sample fit-out 10 | ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM | 11 Floorplate Typical upper floor with suite fit-out 12 | ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM | 13 SOHO TOTTENHAM COURT ROAD MIDTOWN | LONDON Aldwych House, now transformed as part of the dynamic re-generation of this vibrant eclectic midtown destination, stands tall and COVENT GARDEN commanding on the north of the double crescent of Aldwych. -

The Heart of the Empire

The heart of the Empire A self-guided walk along the Strand ww.discoverin w gbrita in.o the stories of our rg lands discovered th cape rough w s alks 2 Contents Introduction 4 Route map 5 Practical information 6 Commentary 8 Credits 30 © The Royal Geographical Society with the Institute of British Geographers, London, 2015 Discovering Britain is a project of the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) The digital and print maps used for Discovering Britain are licensed to the RGS-IBG from Ordnance Survey Cover image: Detail of South Africa House © Mike jackson RGS-IBG Discovering Britain 3 The heart of the Empire Discover London’s Strand and its imperial connections At its height, Britain’s Empire covered one-quarter of the Earth’s land area and one-third of the world’s population. It was the largest Empire in history. If the Empire’s beating heart was London, then The Strand was one of its major arteries. This mile- long street beside the River Thames was home to some of the Empire’s administrative, legal and commercial functions. The days of Empire are long gone but its legacy remains in the landscape. A walk down this modern London street is a fascinating journey through Britain’s imperial history. This walk was created in 2012 by Mike Jackson and Gary Gray, both Fellows of the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG). It was originally part of a series that explored how our towns and cities have been shaped for many centuries by some of the 206 participating nations in the 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games. -

Fine Books, Maps & Manuscripts (SEP18) Lot

Fine Books, Maps & Manuscripts (SEP18) Wed, 12th Sep 2018 Lot 160 Estimate: £2000 - £3000 + Fees Panoramas at Leicester Square. Panoramas at Leicester Square. A collection of 36 plans and descriptions of the various panoramas exhibited at the Panorama, Leicester Square and the Panorama, Strand, London, 1803-40, comprising 21 wood folding wood engraved plans accompanied by descriptive text, 14 folding wood engraved plans without text, and one engraved plan of the Battle of Waterloo, partly hand-coloured, engraved by James Wyld after William Siborne, with accompanying descriptive text entitled Guide to the Model of the Battle of Waterloo, the folding plans various sizes (50 x 38 cm, 19.5 x 15 ins and smaller), a few waterstained or with minor soiling (generally in good condition), all disbound without covers, loose A rare collection of wood engraved plans and descriptions of the various panoramas exhibited to the public by Robert Barker, subsequently his son Henry Aston Barker, and later John and Robert Burford, mainly at the Leicester Square Panorama. First established in Leicester Square in 1793, Robert Barker's purpose built panorama rotunda exhibited 360 degree panoramas painted by the proprietors, with the exception in this present collection of the panorama of St. Petersburg, painted by John Thomas Serres (1759-1825), and the panorama of the Battle of Navarin, painted by John Wilson (1774-1855) and Joseph Cartwright (1789-1829). The folded single-sheet plans comprise: View of Paris. and, in the upper circle, the superb view of Constantinople, -

Grosvenor Prints Catalogue

Grosvenor Prints Tel: 020 7836 1979 19 Shelton Street [email protected] Covent Garden www.grosvenorprints.com London WC2H 9JN Catalogue 110 Item 50. ` Cover: Detail of item 179 Back: Detail of Item 288 Registered in England No. 305630 Registered Office: 2, Castle Business Village, Station Road, Hampton, Middlesex. TW12 2BX. Rainbrook Ltd. Directors: N.C. Talbot. T.D.M. Rainment. C.E. Ellis. E&OE VAT No. 217 6907 49 1. [A country lane] A full length female figure, etched by Eugene Gaujean P.S. Munn. 1810. (1850-1900) after a design for a tapestry by Sir Edward Lithograph. Sheet 235 x 365mm (9¼ x Coley Burne-Jones (1833-98) for William Morris. PSA 14¼")watermarked 'J Whatman 1808'. Ink smear. £90 275 signed proof. Early lithograph, depicting a lane winding through Stock: 56456 fields and trees. Paul Sandby Munn (1773-1845), named after his godfather, Paul Sandby, who gave him his first instructions in watercolour painting. He first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1798 and was a frequent contributor of topographical drawings to that and other exhibtions. Stock: 56472 2. [A water mill] P.S. Munn. [n.d., c.1810.] Lithograph. Sheet 235 x 365mm (9¼ x 14¼"), watermarked 'J Whatman 1808'. Creases £140 Early pen lithograph, depicting a delapidated cottage with a mill wheel. Paul Sandby Munn (1773-1845), named after his godfather, Paul Sandby, who gave him his first instructions in watercolour painting. He first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1798 and was a frequent contributor of topographical drawings to that and other exhibtions. -

Hollywood Panorama

Hollywood Panorama Karen Pinkus On a rundown strip of Hollywood Open limited hours for a small its interim use as a travel agency, Boulevard, at the confluence of two suggested donation, it bore an when Velas moved in, a worn sign neighborhoods recently baptized uncanny resemblance to those (prin- with a golden crown still enticed Thai Town and Little Armenia, the cipally European) nineteenth-century passing drivers to stop for pizza and artist Sara Velas rented an abandoned structures that housed a succession ice cream. fast-food stand with a domed ceiling of proto-cinematic spectacles. The As an icon of local “exotica,” the in 2001, and painted a 360-degree rhetoric, typography and imagery Rotunda had long served as a land- panorama titled Valley of the Smokes. adapted by Velas also referred to mark for motorists. Yet, despite its For about three years, until 2004 this strangely “democratic” period visual prominence, its milieu typified when she lost her lease to a proposed of peepshows, magic lanterns, zoe- the largely bypassed nature of East redevelopment, the “Velaslavasay tropes, and other visual marvels. Hollywood. Adjacent land was par- Panorama” stood as a found object in The building that accommodated tially filled with weeds and rusted car the landscape of Hollywood. Velas’s Panorama, the former South parts. A prop rental agency—Jose’s Seas-themed Tswuun-Tswuun Art Yard—occupied another part of Rotunda, provided an unusual com- the property, displaying Aztec gods plement. Built in 1968 in the exuber- and Rococo fountains cast in plaster. Above: The former site of the Velaslavasay Panorama ant Googie style, it was roofed with Behind was a rather down-and-out at 5553 Hollywood Boulevard. -

A 'Proper Point of View'

A ‘Proper Point of View’: the panorama and some of its early media iterations Early Popular Visual Culture, 9:3, 225-238 (2011) William Uricchio MIT & Utrecht University Abstract: The panorama entered the world not as a visual format but as a claim: to lure viewers into seeing in a particular way. Robert Barker’s 1781 patent for a 360-degree painting emphasized the construction of a ‘proper point of view’ as a means of making the viewer ‘feel as if really on the spot.’ This situating strategy would, over the following centuries, take many forms, both within the world of the painted panorama and its photographic, magic lantern, and cinematic counterparts. This essay charts some of the unexpected twists and turns of this strategy, exploring among others the moving panorama (both as a parallel development to the cinematic moving picture and as deployed by the film medium as a background to suggest movement) and the relations between the spatial promise of the late 19th century stereoscope and that most populous of early motion picture titles, the panorama. The essay focuses on changing technologies and strategies for achieving Barker’s initial goals, while attending to the implications for the viewer. Drawing from the observations of scholars as diverse as Bentham, Foucault, and Crary, the essay uses the various iterations of the panorama to explore the implications of a particularly rich strand of technologies of seeing. William Uricchio is professor and director of Comparative Media Studies at MIT and professor of Comparative Media History at Utrecht University in the Netherlands. 1 A ‘Proper Point of View’: the panorama and some of its early media iterations1 Early Popular Visual Culture, 9:3, 225-238 (2011) http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17460654.2011.601165 William Uricchio MIT & Utrecht University 'I don't have eyes in the back of my head….' is a well known expression.