Home on the Range

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spotted Owl Court Battle

Midweek Edition Thursday, May 16, 2013 $1 Reaching 110,000 Readers in Print and Online — www.chronline.com Veterans Become Tournament Time Pot Growers / Main 6 Fastpitch District Tourney Roundup / Sports Lifeguard Arrested for Allegedly Raping Teen GREAT WOLF LODGE: Great Wolf County Sheriff’s Office. While in the car, Salazar Salazar, who is from the Lodge was ar- The victim told police she allegedly raped the girl, and Ground Mound and Centra- A 19-Year-Old rested Tuesday had befriended the lifeguard, she sustained minor injuries lia area, was arrested at 2:15 Centralia-Area Man after he alleg- identified by police as Alex E. from the sexual assault, said Lt. p.m. Tuesday when deputies Booked into Jail for edly raped a Salazar, at the pool and volun- Greg Elwin, spokesman for the approached him at Rochester 14-year-old girl tarily met with him once his sheriff’s office. Afterward, he High School, which he attends. Third-Degree Rape who was stay- shift was complete, according to dropped the girl back off at the When Salazar saw police at the ing at the hotel a press release from the sheriff’s hotel and she told her family high school, Elwin said, Salazar By Stephanie Schendel made an impromptu statement with her fam- office. At about midnight Tues- what happened. [email protected] Alex E. Salazar of “I messed up.” ily, according accused of rape of day, she got into his car and they The teen told police she did A 19-year-old lifeguard at to the Thurston 14-year-old girl left the property. -

PREFERENCE DATE REPORT Lone Star Park Through 05/27/2018 Page 1 of 8

PREFERENCE DATE REPORT Lone Star Park Through 05/27/2018 Page 1 of 8 Horse Name Dirt Turf Horse Name Dirt Turf Horse Name Dirt Turf --Pretty Meadow(2016) 0 --Geebes(2016) 0 --Stellar Vision(2016) 0 --Katniss 0 --Mari's Big Rock(2016) 0 --My Queen(2016) 0 Everdeen(2016) --Ebony Gift(2016) 0 --Forever Brilliant(2016) 0 --Devil in P1 Diamonds(2015) --Aly's Rita(2016) P3 --Most Magic(2016) 0 --Miss Missile(2016) 0 --Ruby's Big Band(2016) 0 --Pulpitina(2016) 0 A Better Deal 0 A M Milky Way 0 A P's Bluegrass P3 A Place Remembered R21 A. P. Star NC Abbie Secret Way R5 Abigailthelion R22 Aceguitar 0 Aczar P16 Adios Yankee S3 Adore 0 Affaire Secrete R10 Affirming R23 After Hours R23 After Party R21 Air Assault R23 Air Power P17 Alabama Tide R22 Alamo City R14 All About Voodoo R7 All Effort 0 All the Tea R2 Alphabeta nc Alphatime 0 Altuveatbat R7 Alva R8 Always Gray R16 Always Silver R18 Aly Don't Touch P1 Amberson R13 American Colossus P14 American Thunder R21 Americium R21 Amigo Ransom R21 Analyze This Jet R20 And She Scores 0 Andrews Speedracer R21 Angebellanico R10 Angel in My Eyes R15 Another Bond Girl P17 Anothercoincidence 0 Apple County R20 April Sugar 0 Arch Cat R20 Arch of Ages 0 Archiboldo P14 Ardennes R15 Areed R14 Artax Apalachee R20 Aryescelestic Man P1 Ashtabula Five R19 Assembled Lady R8 At Bat 0 At the Hop 0 Atlantis 0 Atotonilco (MEX) R23 Attraction R11 Audacious Angel R15 Augustus Maximus R21 Aunt Lyda nc Aurora Lane R17 Avalo Magnificent R7 Avanzare R23 Averys Miss 0 Awesome J T R22 B Js Arch 0 Baby Spencer 0 Backseat Promises -

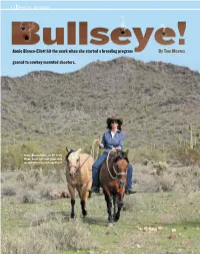

Annie Bianco-Ellett Hit the Mark When She Started a Breeding Program by Tom Moates

≤ horse people Annie Bianco-Ellett hit the mark when she started a breeding program By Tom Moates geared to cowboy mounted shooters. Annie Bianco-Ellett, on El Costa Prom, leads her next-generation up-and-comer Costa Peppy Pistol. 26 MARCH-APRIL 2012 AMERICA’S HORSE TOM MOATES “THE SPORT WAS NEW, AND THERE WEREN’T ANY HORSES BEING that she wouldn’t be the only shooter customizing high-level bred, per se, to do mounted shooting,” says Annie Bianco-Ellett. Quarter Horses to mounted shooting. A problem? Or opportunity? “I realized after that first year that I needed something more Before long, “Outlaw Annie,” a renowned shooter, helped athletic,” she says. “So, enter Costa. A cowboy from Twin Falls, revolutionize the fledgling sport of cowboy mounted shooting Idaho, named Tony Jardine was on this young colt named Costa. by stressing the importance of serious performance horses. And He was at one of the shooting events, and I saw this colt, and it it all began with her stallion and main mount for much of her was just love at first sight. Tony didn’t own him; a Quarter shooting career, El Costa Prom. “Costa’s” get, collectively Horse breeder named Birchie Brown did. Costa worked at the known as the “Costa Colts” or “Costa Kids,” are recognized feedlot during the week, and on weekends, he got to shoot and now as some of the winningest horses in the sport. pick up at rodeos. Birchie wouldn’t sell him. I borrowed him ... In cowboy mounted shooting, participants ride one of 50 and finally, after a couple of years of just basically leasing him, patterns against the clock while using two pistols to hit 10 Birchie broke down and sold him to me. -

DGA Reality Directors Contact Guide

DGA’s REALITY DIRECTORS Contact Guide EF OP CH PRO T JE CT R FACT RU SE FEAR OR N W LO D BI A T E G Y S K K B E A K TAN A R N R ME O G HA R T G G S I H I N C I A E B ’ R T S A F E N D H E C X E R T C E F T T A F O S R O A P G E M M C N O I A Z F D A E R L M O I A R R E R T S S A I E A B W S D R T M A P A O T J K N A E K I E E N Y E V I B N N A C L A I R M E E A S T K M A U M L I E L T E L R C U H C A I L L A C E E N G A R N G G A R R I D T S ’ L U R A U P 7/2018 WHAT PRODUCERS AND AGENTS ARE SAYING ABOUT DGA REALITY AGREEMENTS: “The DGA has done an amazing job of building strong relationships with unscripted Producers. They understand that each show is different and work with us to structure deals that make sense for both the Producers and their Members on projects of all sizes and budgets. -

PREFERENCE DATE REPORT Lone Star Park Through 06/03/2018 Page 1 of 8

PREFERENCE DATE REPORT Lone Star Park Through 06/03/2018 Page 1 of 8 Horse Name Dirt Turf Horse Name Dirt Turf Horse Name Dirt Turf --Pretty Meadow(2016) 0 --Geebes(2016) 0 --Stellar Vision(2016) 0 --Katniss 0 --Mari's Big Rock(2016) 0 --My Queen(2016) 0 Everdeen(2016) --Ebony Gift(2016) 0 --Forever Brilliant(2016) 0 --Devil in P1 Diamonds(2015) --Aly's Rita(2016) P3 --Most Magic(2016) 0 --Miss Missile(2016) 0 --Ruby's Big Band(2016) 0 --Pulpitina(2016) 0 A Better Deal 0 A M Milky Way 0 A P's Bluegrass P3 A Place Remembered R21 A. P. Star NC Abbie Secret Way R26 Abigailthelion R22 Aceguitar 0 Aczar R26 Adios Yankee S3 Adore 0 Affaire Secrete R10 Affirming R23 After Hours R23 After Party R21 Air Assault R23 Air Power P17 Alabama Tide R22 Alamo City R25 All About Voodoo R7 All Effort 0 All the Tea R2 Alphabeta nc Alphatime 0 Altuveatbat R24 Alva R8 Always Gray R24 Always Silver R18 Aly Don't Touch P1 Amberson R13 American Colossus P14 American Thunder R21 Americium R21 Amigo Ransom R21 Analyze This Jet R20 And She Scores 0 Andrews Speedracer R26 Angebellanico R10 Angel in My Eyes R15 Another Bond Girl P17 Apple County R20 April Sugar 0 Arch Cat R20 Arch of Ages 0 Archiboldo R24 Ardennes R25 Areed R14 Artax Apalachee R20 Aryescelestic Man P1 Ashtabula Five R26 Assembled Lady R26 At the Hop 0 Atlantis 0 Atotonilco (MEX) R23 Attraction R25 Audacious Angel R15 Augustus Maximus R21 Aunt Lyda nc Aurora Lane R17 Avalo Magnificent R7 Avanzare R23 Averys Miss 0 Awesome J T R22 B Js Arch 0 Baby Spencer 0 Backseat Promises R22 Backyard Hero R20 Bad -

Parody As a Borrowing Practice in American Music, 1965–2015

Parody as a Borrowing Practice in American Music, 1965–2015 A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music by John P. Thomerson BM, State University of New York at Fredonia, 2008 MM, University of Louisville, 2010 Committee Chair: bruce d. mcclung, PhD ABSTRACT Parody is the most commonly used structural borrowing technique in contemporary American vernacular music. This study investigates parody as a borrowing practice, as a type of humor, as an expression of ethnic identity, and as a response to intellectual trends during the final portion of the twentieth century. This interdisciplinary study blends musicology with humor studies, ethnic studies, and intellectual history, touching on issues ranging from reception history to musical meaning and cultural memory. As a structural borrowing technique, parody often creates incongruity—whether lyrical, stylistic, thematic, evocative, aesthetic, or functional—within a recognized musical style. Parodists combine these musical incongruities with other comic techniques and social conventions to create humor. Parodists also rely on pre-existing music to create, reinforce, and police ethnic boundaries, which function within a racialized discourse through which parodists often negotiate ethnic identities along a white-black binary. Despite parody’s ubiquity in vernacular music and notwithstanding the genre’s resonance with several key themes from the age of fracture, cultivated musicians have generally parody. The genre’s structural borrowing technique limited the identities musicians could perform through parodic borrowings. This study suggests several areas of musicological inquiry that could be enriched through engagement with parody, a genre that offers a vast and largely unexplored repertoire indicating how musical, racial, and cultural ideas can circulate in popular discourse. -

Film and Television Projects Made in Texas (1910 – 2021) Page 1 of 36

Film and Television Projects Made in Texas (1910 – 2021) Page 1 of 36 PROJECT NAME TYPE PRODUCTION COMPANY PRODUCTION DATE(S) CITY/TOWN SHOT IN MAGNOLIA TABLE - SEASON 4 TV Series (Network/Cable/Digital) Blind Nil LLC 2021-06-14 – 2021-07-02 Valley Mills; Waco MAGNOLIA TABLE - SEASON 3 TV Series (Network/Cable/Digital) Blind Nil LLC 2021-04-06 – 2021-04-23 Valley Mills Austin; College Station; Fredericksburg; San QUEER EYE - SEASON 6 TV Series (Network/Cable/Digital) Netflix / LWT Enterprises 2021-03-22 – 2021-07-02 Antonio BBQ BRAWL - SEASON 3 TV Series (Network/Cable/Digital) Rock Shrimp Productions 2021-02-22 – 2021-04-02 Austin; Bee Cave; Buda; Cedar Park; Manor Bee Cave; Driftwood; Dripping Springs; BBQ BRAWL - SEASON 2 TV Series (Network/Cable/Digital) Rock Shrimp Productions 2021-02-22 – 2021-04-01 Fredericksburg; Luckenbach Highland Haven; South Padre Island; LAKEFRONT BARGAIN HUNT - SEASON 12 TV Series (Network/Cable/Digital) Magilla Entertainment 2021-01-27 – 2021-06-10 Surfside Beach Rebel 6 Films / TLG Motion FREE DEAD OR ALIVE Feature (Independent) Pictures 2021-01-24 – 2021-03-03 Alpine; Austin; Buda; Lajitas; Terlingua READY TO LOVE - SEASON 3 TV Series (Network/Cable/Digital) Light Snack Media, LLC 2021-01-20 – 2021-03-27 Houston MAGNOLIA TABLE - SEASON 2 TV Series (Network/Cable/Digital) Blind Nil LLC 2021-01-18 – 2021-01-28 Valley Mills VAN GO TV Series (Network/Cable/Digital) Rabbit Foot Studios 2020-11-17 – 2021-05-12 Austin Austin; Bartlett; Bastrop; Lockhart; WALKER - SEASON 1 TV Series (Network/Cable/Digital) CBS -

Sweepstakes Drawing, Email Address (Optional) Please Fill out the Form on the Left

Non-HispanicPages1-2 4/21/05 6:13 AM Page 1 National Consumer Survey www.SimmonsSurvey.com THANKS FOR TAKING PART IN THIS IMPORTANT CONSUMER SURVEY. AKESKLET ST RM AND $2,000OMPLETED BOO OMPLETEOUR THIS CO WIN FO $2,000!! SY! C ’S EA IT ONG WITH Y SWEEPOUR CHANCE T R Y MAIL ITFO AL Name If you have any questions about the Simmons National Consumer Survey, Address please call 1-800-551-6425, or visit our website at www.SimmonsSurvey.com. We will be pleased to help you. City This is your opportunity to tell businesses and advertisers about the State products you like and the types of media you prefer. PLEASE MAKE YOUR OPINIONS COUNT BY Zip Code COMPLETING THIS BOOKLET. Your survey starts on Page 4. Phone Number If you would like to be entered into the $2,000 Sweepstakes drawing, Email Address (Optional) please fill out the form on the left. Non-HispanicPages1-2 4/21/05 6:13 AM Page 2 National Consumer Survey www.SimmonsSurvey.com Sweepstakes Official Rules 1. NO PURCHASE NECESSARY. To enter, neatly complete the front of this form (including your name and complete address) and return completed booklet in the enclosed postage paid envelope. One entry per person. No mechanically produced entries will be accepted. Sweepstakes begins May 21, 2005, and your entry must be received by the date on the front cover of this booklet. 2. On or about October 31, 2005, AKES winners will be selected in a random drawing from among all eligible entries ST received by Simmons Market Research Bureau, Inc. -

With a Smile on Her Face

MLB: Tampa Bay takes on AL East rival Toronto /B1 WEDNESDAY TODAY CITRUS COUNTY & next morning HIGH 82 A nice day with LOW plentiful sunshine. PAGE A4 54 www.chronicleonline.com MAY 8, 2013 Florida’s Best Community Newspaper Serving Florida’s Best Community 50¢ VOL. 118 ISSUE 274 Commission OKs new fire service fee County Attorney Richard Wesch tion policy, advising adoption of or MSTU that is based on tax- Adams suggests public referendum advised the board as mem- exemptions for government able value) moved to the MSBU. bers formed the motion. parcels and institutional tax- Commission Chairman Joe CHRIS VAN ORMER vote, agreed to proceed with the Wesch explained that similar exempt parcels, but taking no Meek said under the motion Staff writer implementation of a municipal to the MSBU for solid waste action on hardship exemption or Bays’ request was possible be- services benefit unit (MSBU) for management, which is set at $25 vacancy credit for mobile cause the range of $100 to $53 INVERNESS — The first step fire services. The rate under dis- per year but could be raised to home/RV parks. offered a “big window.” was taken Tuesday to change the cussion is $100 down to $53 per as much as $100 per year, the fire Commissioner Dennis Damato “Keep in mind that if the BU appearance of next year’s tax residential unit. service MSBU rate could be re- moved approval, seconded by rate is at $100, your TU millage bills with the inclusion of a flat “To keep our options open as evaluated annually. -

'E' ££££ 2081612X 'O Sole Mio ££££ 18003

Tunecode Title Value Range 135570CR $5 Blues Lick-Spm0157.Aif ££££ 132448AV 'e' ££££ 2081612X 'o Sole Mio ££££ 180032KN -Funny- ££££ 260280AT ...Familiar Place ££££ 8584597K 0.166666667 ££££ 278704KR 0163782-Corporate_Cool_15s ££££ 139286GT 1 4 The Treble ££££ 154304ER 1,000 To 1 Cues ££££ 107012BU 100 Bottles ££££ 5138660E 10000 Miles ££££ 9540738Z 101 Dalmatians ££££ 6132034E 107.8 Radio Jackie ££££ 251724KQ 12 Reinventions For George Russe ££££ 188899GW 140 Man At Ya Door ££££ 147133FU 16 Shades Of Blue ££££ 124861BS 165513_6-10 Uk TV Music ££££ 224829DT 184 Full 4th Of July 0133 ££££ 8368302C 1840-1900 The Light And Dark Sid ££££ 141872LQ 1911 ££££ 271697LT 1982 ££££ 141904BP 1m05 Clean Up Plan ££££ 157765HS 1st Take Magic ££££ 249732FM 2 Hr Specials ££££ 2240176C 22 Blues ££££ 0651844X 2:1 ££££ 089097KR 2m20 ££££ 234571GN 2nd Hand Joy ££££ 174417AT 3 Options ££££ 6097631Z 3-4.3 9/11 ££££ 126940KR 30 Billboard ££££ 263829FT 30 For 30 ££££ 148505LQ 30 Seconds Of Death Metal ££££ 222061KS 30 Years Of Greatness ££££ 238682CP 3rd Movement In B Flat ££££ 4841534E 4 Am ££££ 180737HU 4 O'Clock Files ££££ 228598CM 4 Songs ££££ 152535CS 40 Days And 40 Nights ££££ 133226ER 4music Brand Manifesto June 2013 ££££ 133730CN 5 Good Men ££££ 143119CU 58 Bpm ££££ 086992GW 6 Degrees Squeezer Mix ££££ 089098GU 6m1 ££££ 137214CP 7 Chapters ££££ 276130CR 9 Letter Love Song ££££ 092771DP A Bhirlinn Bharrach ££££ 152815LS A Bugs Life ££££ 144190LN A Child's Hymn ££££ 138298ER A Christmas Tail ££££ 232771LN A Curious Cat ££££ 253505GS A Date To Die For ££££ -

Copyright by Patrick Schultz 2017

Copyright by Patrick Schultz 2017 The Dissertation Committee for Patrick Schultz Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Gender Variation in Writing: Analyzing Online Dating Ads Committee: Lars Hinrichs, Supervisor Mary E Blockley Katrin Erk Jacqueline M Henkel Gender Variation in Writing: Analyzing Online Dating Ads by Patrick Schultz, BA, MA Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2017 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my family: my parents Susanne and Christoph, my little sisters Fiona, Alison, and Catriona, my grandmothers Erika Fritz and Marianne Schultz, and my godmother Barbara Wittemann. Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge my dissertation supervisor, Lars Hinrichs, without whose feedback and ideas this project would not have been possible. Thank you for your support throughout this process. I wish to thank my committee members, Mary Blockley, Jacqueline Henkel, and Katrin Erk, who were more than generous with their expertise and time. Thank you for serving on my committee. I would also like to thank everyone at the Digital Writing and Research Lab at the University of Texas at Austin, especially program coordinator Will Burdette, for kindly letting me use their lab facilities and equipment. Many thanks to all of you! v Gender Variation in Writing: Analyzing Online Dating Ads Patrick Schultz, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Austin, 2017 Supervisor: Lars Hinrichs This dissertation presents a study of gendered language variation and linguistic indexicality in computer-mediated communication. -

Hedges 1 Cinematic Memory and the Southern Imaginary: Crisis in The

Hedges 1 Cinematic Memory and the Southern Imaginary: Crisis in the Deep South and The Phenix City Story Gareth Robert Andrew Hedges A Thesis in the Department of the Humanities Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Concordia University Montréal, Québec, Canada June 2016 © Gareth Robert Andrew Hedges, 2016 Hedges 2 Hedges iii Abstract Cinematic Memory and the Southern Imaginary: Crisis in the Deep South and The Phenix City Story Gareth Hedges, Ph.D. Concordia University, 2016 This dissertation is a historical and theoretical study of the southern imaginary at the intersection of mass and regional culture. The focus is on two cinematic treatments of significant violent crimes in the region during the 1950s: firstly, the assassination of Albert Patterson, which prompted the clean of the “wide open” town of Phenix City, Alabama; and secondly, the murder of Emmett Till in Mississippi, which played a critical role in accelerating the African American freedom struggle. The Phenix City Story (Allied Artists, 1955), and Crisis in the Deep South, an unproduced 1956 screenplay written by Crane Wilbur, were both products of the media frenzy surrounding these actual events and they each involved investigation and research into local circumstances as part of their development and production. Rooted in film studies, history and cultural studies, the method of this thesis is to look backward to the foundational elements of the texts in question (e.g., the ‘raw material’ of the actual historical events,), and forward to the consequences of cinematic intervention into local commemorative regimes. In this way, I chart how the overlaps and interconnections between these film projects and others of the era reveal the emergence, consolidation and dissolution of a larger “cycles of sensation,” a concept outlined by Frank Krutnik and Peter Stanfield.