Surveillance Protocol for Undifferentiated Pustular / Vesicular Rash Illness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guidelines for Case-Based Reporting

澳門特別行政區 傳染病強制申報機制 Macao SAR Notifiable Communicable Diseases Guidelines for Case-based Reporting (FIRST DRAFT) 2008 澳門特別行局區政府衛生局 Health Bureau, Government of Macao Special Administrative Region ii iii Contents Contents ............................................................................................................................................................ iii Signs and abbreviations .................................................................................................................................... 5 Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) ............................................................................................... 6 Acute gastroenteropathy due to Norwalk agent (ICD-9 : 008.6, ICD-10 : A08.1 ) ...................................... 11 Acute haemorrhagic conjunctivitis (ICD-9 : 077, ICD-10 : B30.3 ) ............................................................. 12 Acute poliomyelitis ICD-9 045 ICD-10 A80 ................................................................................... 13 Amoebiasis ICD-9 006 ICD-10 A06 ............................................................................................... 14 Anogenital herpesviral (herpes simplex) infection ICD-9 054 ICD-10 A60 ............................... 16 Anthrax ICD-9 022 ICD-10 A22 .................................................................................................. 17 Chickenpox (Varicella) ICD-9 052 ICD-10 B01 ............................................................................ 19 Cholera ICD-9 -

Concurrent Beau Lines, Onychomadesis, and Retronychia Following Scurvy

CASE REPORT Concurrent Beau Lines, Onychomadesis, and Retronychia Following Scurvy Dayoung Ko, BS; Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD the proximal nail plate from the distal nail plate leading to shedding of the nail. It occurs due to a complete growth PRACTICE POINTS arrest in the nail matrix and is thought to be on a con- • Beau lines, onychomadesis, and retronychia are nail tinuum with Beau lines. The etiologies of these 2 condi- conditions with distinct clinical findings. tions overlap and include trauma, inflammatory diseases, • Beau lines and onychomadesis may be seen 1-5 concurrently following trauma, inflammatory dis- systemic illnesses, hereditary conditions, and infections. eases, systemic illnesses, hereditary conditions, In almost all cases of both conditions, normal nail plate and infections. production ensues upon identification and removal of the 3,4,6 • Retronychia shares a common pathophysiology inciting agent or recuperation from the causal illness. with Beau lines and onychomadesis, and all reflect Beau lines will move distally as the nail grows out and slowing or cessation of nail plate production. can be clipped. In onychomadesis, the affected nails will be shed with time. Resolution of these nail defects can be estimated from average nail growth rates (1 mm/mo for fingernails and 2–3 mm/mo for toenails).7 Beau lines, onychomadesis, and retronychia are nail conditions with Retronychia is defined as a proximal ingrowing of their own characteristic clinical findings. It has been hypothesized the nail plate into the ventral surface of the proximal nail that these 3 disorders may share a common pathophysiologic fold.4,6 It is thought to occur via vertical progression of mechanism of slowing and/or halting nail plate production at the the nail plate into the proximal nail fold, repetitive nail nail matrix. -

Livedoid Vasculopathy Associated with Peripheral Neuropathy: a Report of Two Cases* Vasculopatia Livedoide Associada a Neuropatia Periférica: Relato De Dois Casos

CASE REPORT 227 s Livedoid vasculopathy associated with peripheral neuropathy: a report of two cases* Vasculopatia livedoide associada a neuropatia periférica: relato de dois casos Mariana Quirino Tubone1 Gabriela Fortes Escobar1 Juliano Peruzzo1 Pedro Schestatsky2 Gabriela Maldonado3 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/abd1806-4841.20132363 Abstract: Livedoid vasculopathy (LV) is a chronic and recurrent disease consisting of livedo reticularis and sym- metric ulcerations, primarily located on the lower extremities, which heal slowly and leave an atrophic white scar ("atrophie blanche"). Neurological involvment is rare and presumed to be secondary to the ischemia from vascu- lar thrombosis of the vasa nervorum. Laboratory evaluation is needed to exclude secondary causes such as hyper- coagulable states, autoimmune disorders and neoplasms. We present two patients with a rare association of peripheral neuropathy and LV, thereby highlighting the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to reach the correct diagnosis. Keywords: Livedo reticularis; Mononeuropathies; Polyneuropathies; Skin diseases, vascular Resumo: Vasculopatia livedoide é uma doença crônica e recorrente caracterizada por livedo reticular e úlceras simétricas nos membros inferiores, que cicatrizam e deixam uma cicatriz branca atrófica ("atrophie blanche"). Envolvimento neurológico é raro e está provavelmente associado a isquemia pela trombose dos vasa nervorum. Avaliação laboratorial é indicada com o intuito de excluir causas secundárias como estados de hipercoagulabili- dade, doenças autoimunes e neoplasias. Apresentamos dois pacientes com uma rara associação de vasculopatia livedoide com neuropatia periférica, enfatizando a importância de uma abordagem multidisciplinar na busca do diagnóstico correto. Palavras-chave: Dermatopatias vasculares; Livedo reticular; Mononeuropatias; Polineuropatias INTRODUCTION Livedoid vasculopathy (LV) is a chronic and resentation of the dermo-hypodermic junction, was recurrent disease, usually restricted to the skin, and compatible with LV. -

Truncal Rashes Stan L

Healthy Baby Practical advice for treating newborns and toddlers. Getting Truculent with Truncal Rashes Stan L. Block, MD, FAAP A B C All images courtesy of Stan L. Block, MD, FAAP. Figure 1. Afebrile 22-month-old white male presents to your office with this slowly spreading, somewhat generalized, and refractory truncal rash for the past 4 weeks. It initially started on the right side of his trunk (A) and later extended down his right upper thigh (B). The rash has now spread to the contralateral side on his back (C), and is most confluent and thickest over his right lateral ribs. n a daily basis, we pediatricians would not be readily able to identify this rash initially began on the right side of his encounter a multitude of rashes relatively newly described truncal rash trunk (see Figure 1A) and then extended O of varied appearance in children shown in some of the following cases. distally down to his right upper thigh (see of all ages. Most of us gently-seasoned As is typical, certain clues are critical, Figure 1B). Although the rash is now dis- clinicians have seen nearly all versions including the child’s age, the duration tributed over most of his back (see Figure of these “typical” rashes. Yet, I venture and the distribution of the rash. Several 1C), it is most confluent and most dense to guess that many practitioners, who of these rashes notably mimic more com- over his right lateral ribs. would be in good company with some of mon etiologies, as discussed in some of From Figure 1, you could speculate my quite erudite partners (whom I asked), the following cases. -

Cerebral Venous Thrombosis and Livedo Reticularis in a Case with MTHFR 677TT Homozygote

Journal of Clinical Neurology / Volume 2 / June, 2006 Case Report Cerebral Venous Thrombosis and Livedo Reticularis in a Case with MTHFR 677TT Homozygote Jee-Young Lee, M.D., Manho Kim, M.D., Ph.D. Department of Neurology, College of Medicine, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea Hyperhomocysteinemia associated with methylene terahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) mutation can be a risk factor for idiopathic cerebral venous thrombosis. We describe the first case of MTHFR 677TT homozygote with cerebral venous thrombosis and livedo reticularis. A 45-year-old man presented with seizures and mottled-like skin lesions, that were aggravated by cold temperature. Hemorrhagic infarct in the right frontoparietal area with superior sagittal sinus thrombosis was observed. He had hyperhomocysteinemia, low plasma folate level, and MTHFR 677TT homozygote genotype, which might be associated with livedo reticularis and increase the risk for cerebral venous thrombosis. J Clin Neurol 2(2):137-140, 2006 Key Words : Livedo reticularis, Methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase, Cerebral venous thrombosis Hyperhomocysteinemia causes vascular endothelial venous infarct due to cerebral venous thrombosis. damage that result in atherosclerosis and ischemic strokes.1 It is also associated with prothrombotic state or venous thromboembolism2 including cerebral venous CASE REPORT thrombosis.3 Among the thrombophilic factors with hyperhomocysteinemia, methylene tetrahydrofolate reduc- A 45 year-old man was brought to the emergency tase (MTHFR) mutant (C677 → T, homozygote) with room with uncontrolled seizures. Two days ago, sudden low plasma folate concentration increases the risk for paresthesia in left arm developed, which progressed to cerebral venous thrombosis.4 MTHFR 677TT is thermo- tonic posturing and leftward head version, followed by labile and sensitive to temperature alteration.5 a generalized tonic clonic seizure. -

Fundamentals of Dermatology Describing Rashes and Lesions

Dermatology for the Non-Dermatologist May 30 – June 3, 2018 - 1 - Fundamentals of Dermatology Describing Rashes and Lesions History remains ESSENTIAL to establish diagnosis – duration, treatments, prior history of skin conditions, drug use, systemic illness, etc., etc. Historical characteristics of lesions and rashes are also key elements of the description. Painful vs. painless? Pruritic? Burning sensation? Key descriptive elements – 1- definition and morphology of the lesion, 2- location and the extent of the disease. DEFINITIONS: Atrophy: Thinning of the epidermis and/or dermis causing a shiny appearance or fine wrinkling and/or depression of the skin (common causes: steroids, sudden weight gain, “stretch marks”) Bulla: Circumscribed superficial collection of fluid below or within the epidermis > 5mm (if <5mm vesicle), may be formed by the coalescence of vesicles (blister) Burrow: A linear, “threadlike” elevation of the skin, typically a few millimeters long. (scabies) Comedo: A plugged sebaceous follicle, such as closed (whitehead) & open comedones (blackhead) in acne Crust: Dried residue of serum, blood or pus (scab) Cyst: A circumscribed, usually slightly compressible, round, walled lesion, below the epidermis, may be filled with fluid or semi-solid material (sebaceous cyst, cystic acne) Dermatitis: nonspecific term for inflammation of the skin (many possible causes); may be a specific condition, e.g. atopic dermatitis Eczema: a generic term for acute or chronic inflammatory conditions of the skin. Typically appears erythematous, -

Tips for Managing Treatment-Related Rash and Dry Skin

RASH Tips for Managing Treatment-Related Rash and Dry Skin Presented by Stewart B. Fleishman, MD Continuum Cancer Centers of New York: Beth Israel & St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Lindy P. Fox, MD University of California San Francisco David H. Garfield, MD University of Colorado Comprehensive Cancer Center Carol S. Viele, RN, MS University of California San Francisco Carolyn Messner, DSW CancerCare Learn about: • Effects of targeted treatments on the skin • Managing rashes and dry skin • Treating nail conditions • Your support team Help and Hope CancerCare is a national nonprofit organization that provides free support services to anyone affected by cancer: people with cancer, caregivers, children, loved ones, and the bereaved. CancerCare programs—including counseling and support groups, education, financial assistance, and practical help—are provided by professional oncology social workers and are completely free of charge. Founded in 1944, CancerCare provided individual help to more than 100,000 people last year and had more than 1 million unique visitors to our websites. For more information, call 1-800-813-HOPE (4673) or visit www.cancercare.org. Contacting CancerCare National Office Administration CancerCare Tel: 212-712-8400 The material presented in this patient booklet is provided for your general 275 Seventh Avenue Fax: 212-712-8495 information only. It is not intended as medical advice and should not be relied New York, NY 10001 Email: [email protected] upon as a substitute for consultations with qualified health professionals who Email: [email protected] Website: www.cancercare.org are aware of your specific situation. We encourage you to take information and Services questions back to your individual health care provider as a way of creating a Tel: 212-712-8080 dialogue and partnership about your cancer and your treatment. -

Measles Clinical Guidance: Identification & Testing of Suspect Measles Cases

June 2019 Measles Clinical Guidance: Identification & Testing of Suspect Measles Cases The United States declared measles eliminated in 2000, meaning that there is not endemic transmission within the country and reported cases are due to infection while visiting another country. Measles continues to circulate in much of the world, including Europe, Asia and Africa. International travel, domestic travel through international airports, and contact with international visitors can pose a risk for exposure to measles. When measles is imported into the United States, additional transmission can occur locally. While providers should consider measles in patients with fever and a descending rash, measles is unlikely in the absence of confirmed measles cases in your community or a history of travel or exposure to travelers. This guidance discusses which patients should be prioritized for measles testing. Testing for measles should be based on: A) Measles symptoms: • Fever, including subjective fever. • Rash that starts on the head and descends. • Usually 1 or 2 of the 3 “Cs” – cough, coryza and conjunctivitis. B) Risk factors increasing the likelihood of a measles diagnosis: • In the prior 3 weeks: travel outside of North America, transit through U.S. international airports, or interaction with foreign visitors, including at a U.S. tourist attraction. • Confirmed measles cases in your community. • Never immunized with measles vaccine and born in 1957 or later. NOTE: Fever and rash occur in approximately 5% of MMR vaccine recipients, typically 6-12 days after immunization. Such reactions can be clinically identical to measles infection, and result in positive laboratory testing for measles. This reflects an immune response due to exposure to measles vaccine virus rather than wild measles virus and the patient is not infectious. -

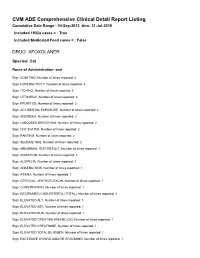

FDA CVM Comprehensive ADE Report Listing for Afoxolaner

CVM ADE Comprehensive Clinical Detail Report Listing Cumulative Date Range : 04-Sep-2013 -thru- 31-Jul-2018 Included 1932a cases = : True Included Medicated Feed cases = : False DRUG: AFOXOLANER Species: Cat Route of Administration: oral Sign: VOMITING, Number of times reported: 4 Sign: HYPERACTIVITY, Number of times reported: 3 Sign: ITCHING, Number of times reported: 3 Sign: LETHARGY, Number of times reported: 3 Sign: PRURITUS, Number of times reported: 3 Sign: ACCIDENTAL EXPOSURE, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: ANOREXIA, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: LABOURED BREATHING, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: NOT EATING, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: PANTING, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: SEIZURE NOS, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: ABNORMAL TEST RESULT, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: AGITATION, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ALOPECIA, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ANAEMIA NOS, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ATAXIA, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: CERVICAL VENTROFLEXION, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: CONSTIPATION, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: DECREASED CHOLESTEROL (TOTAL), Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED ALT, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED AST, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED BUN, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED CREATINE-KINASE (CK), Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED CREATININE, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED TOTAL BILIRUBIN, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: EXCESSIVE LICKING AND/OR GROOMING, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: FEVER, -

Drug Eruptions- When to Worry

3/17/2017 Drug reactions: Drug Eruptions‐ When to Worry 3 things you need to know 1. Type of drug reaction 2. Statistics: – Which drugs are most likely to cause that type of Lindy P. Fox, MD reaction? Associate Professor 3. Timing: Director, Hospital Consultation Service – How long after the drug started did the reaction Department of Dermatology University of California, San Francisco begin? [email protected] I have no conflicts of interest to disclose 1 Drug Eruptions: Common Causes of Cutaneous Drug Degrees of Severity Eruptions • Antibiotics Simple Complex • NSAIDs Morbilliform drug eruption Drug hypersensitivity reaction Stevens-Johnson syndrome •Sulfa (SJS) Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) • Allopurinol Minimal systemic symptoms Systemic involvement • Anticonvulsants Potentially life threatening 1 3/17/2017 Morbilliform (Simple) Drug Eruption Morbilliform (Simple) Drug Eruption Per the drug chart, the most likely culprit is: Per the drug chart, the most likely culprit is: Day Day Day ‐> ‐8 ‐7 ‐6 ‐5 ‐4 ‐3 ‐2 ‐1 0 1 Day ‐> ‐8 ‐7 ‐6 ‐5 ‐4 ‐3 ‐2 ‐1 0 1 A vancomycin x x x x A vancomycin x x x x B metronidazole x x B metronidazole x x C ceftriaxone x x x C ceftriaxone x x x D norepinephrine x x x D norepinephrine x x x E omeprazole x x x x E omeprazole x x x x F SQ heparin x x x x F SQ heparin x x x x trimethoprim/ trimethoprim/ G xxxxxxx G xxxxxxx sulfamethoxazole sulfamethoxazole Admit day Rash onset Admit day Rash onset Morbilliform (Simple) Drug Eruption Drug Induced Hypersensitivity Syndrome • Begins 5‐10 days after drug started -

Ekbom Syndrome: a Delusional Condition of “Bugs in the Skin”

Curr Psychiatry Rep DOI 10.1007/s11920-011-0188-0 Ekbom Syndrome: A Delusional Condition of “Bugs in the Skin” Nancy C. Hinkle # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC (outside the USA) 2011 Abstract Entomologists estimate that more than 100,000 included dermatophobia, delusions of infestation, and Americans suffer from “invisible bug” infestations, a parasitophobic neurodermatitis [2••]. Despite initial publi- condition known clinically as Ekbom syndrome (ES), cations referring to the condition as acarophobia (fear of although the psychiatric literature dubs the condition “rare.” mites), ES is not a phobia, as the individual is not afraid of This illustrates the reluctance of ES patients to seek mental insects but rather convinced that they are infesting his or health care, as they are convinced that their problem is her body [3, 4]. This paper deals with primary ES, not the bugs. In addition to suffering from the delusion that bugs form secondary to underlying psychological or physiologic are attacking their bodies, ES patients also experience conditions such as drug reaction or polypharmacy [5–8]. visual and tactile hallucinations that they see and feel the While Morgellons (“the fiber disease”) is likely a compo- bugs. ES patients exhibit a consistent complex of attributes nent on the same delusional spectrum, because it does not and behaviors that can adversely affect their lives. have entomologic connotations, it is not included in this discussion of ES [9, 10]. Keywords Parasitization . Parasitosis . Dermatozoenwahn . Valuable reviews of ES include those by Ekbom [1](1938), Invisible bugs . Ekbom syndrome . Bird mites . Infestation . Lyell [11] (1983), Trabert [12] (1995), and Bak et al. -

What Are Panic Attacks?

What are Panic Attacks? Understanding the body’s “Fight or Flight” response to a threat. We all have a built-in alarm system that turns on automatically to make sure we survive whatever danger triggers it. This alarm is a lot like a burglar alarm on a house; once it detects something that might be a threat, it automatically sets off several events. If someone were breaking into your house, you would want the alarm system to call the police immediately. You would also likely want to turn on lights and even sound an audible alarm to wake you and scare off the intruder. The brain’s alarm system sets off a series of events as well, commonly called the “fight or flight” response. The fight or flight response is meant to put us in a state of high alert so that we can fight off an enemy or flee to escape with our lives. This alarm makes us faster and stronger and more focused than we would normally be. Our ancestors may not have survived if the human body was not hardwired with the fight or flight response. The reaction is automatic. It helps us survive, and we do not have to think about it; it just happens. But because it is automatic, we do not get to choose which things will set it off. Sometimes, the fight or flight response can start firing if it thinks there is danger, even when there isn’t any real threat around. This is especially common in people who have been through a traumatic event.