Measles Clinical Guidance: Identification & Testing of Suspect Measles Cases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fundamentals of Dermatology Describing Rashes and Lesions

Dermatology for the Non-Dermatologist May 30 – June 3, 2018 - 1 - Fundamentals of Dermatology Describing Rashes and Lesions History remains ESSENTIAL to establish diagnosis – duration, treatments, prior history of skin conditions, drug use, systemic illness, etc., etc. Historical characteristics of lesions and rashes are also key elements of the description. Painful vs. painless? Pruritic? Burning sensation? Key descriptive elements – 1- definition and morphology of the lesion, 2- location and the extent of the disease. DEFINITIONS: Atrophy: Thinning of the epidermis and/or dermis causing a shiny appearance or fine wrinkling and/or depression of the skin (common causes: steroids, sudden weight gain, “stretch marks”) Bulla: Circumscribed superficial collection of fluid below or within the epidermis > 5mm (if <5mm vesicle), may be formed by the coalescence of vesicles (blister) Burrow: A linear, “threadlike” elevation of the skin, typically a few millimeters long. (scabies) Comedo: A plugged sebaceous follicle, such as closed (whitehead) & open comedones (blackhead) in acne Crust: Dried residue of serum, blood or pus (scab) Cyst: A circumscribed, usually slightly compressible, round, walled lesion, below the epidermis, may be filled with fluid or semi-solid material (sebaceous cyst, cystic acne) Dermatitis: nonspecific term for inflammation of the skin (many possible causes); may be a specific condition, e.g. atopic dermatitis Eczema: a generic term for acute or chronic inflammatory conditions of the skin. Typically appears erythematous, -

FDA CVM Comprehensive ADE Report Listing for Afoxolaner

CVM ADE Comprehensive Clinical Detail Report Listing Cumulative Date Range : 04-Sep-2013 -thru- 31-Jul-2018 Included 1932a cases = : True Included Medicated Feed cases = : False DRUG: AFOXOLANER Species: Cat Route of Administration: oral Sign: VOMITING, Number of times reported: 4 Sign: HYPERACTIVITY, Number of times reported: 3 Sign: ITCHING, Number of times reported: 3 Sign: LETHARGY, Number of times reported: 3 Sign: PRURITUS, Number of times reported: 3 Sign: ACCIDENTAL EXPOSURE, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: ANOREXIA, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: LABOURED BREATHING, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: NOT EATING, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: PANTING, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: SEIZURE NOS, Number of times reported: 2 Sign: ABNORMAL TEST RESULT, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: AGITATION, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ALOPECIA, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ANAEMIA NOS, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ATAXIA, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: CERVICAL VENTROFLEXION, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: CONSTIPATION, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: DECREASED CHOLESTEROL (TOTAL), Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED ALT, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED AST, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED BUN, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED CREATINE-KINASE (CK), Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED CREATININE, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: ELEVATED TOTAL BILIRUBIN, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: EXCESSIVE LICKING AND/OR GROOMING, Number of times reported: 1 Sign: FEVER, -

Ekbom Syndrome: a Delusional Condition of “Bugs in the Skin”

Curr Psychiatry Rep DOI 10.1007/s11920-011-0188-0 Ekbom Syndrome: A Delusional Condition of “Bugs in the Skin” Nancy C. Hinkle # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC (outside the USA) 2011 Abstract Entomologists estimate that more than 100,000 included dermatophobia, delusions of infestation, and Americans suffer from “invisible bug” infestations, a parasitophobic neurodermatitis [2••]. Despite initial publi- condition known clinically as Ekbom syndrome (ES), cations referring to the condition as acarophobia (fear of although the psychiatric literature dubs the condition “rare.” mites), ES is not a phobia, as the individual is not afraid of This illustrates the reluctance of ES patients to seek mental insects but rather convinced that they are infesting his or health care, as they are convinced that their problem is her body [3, 4]. This paper deals with primary ES, not the bugs. In addition to suffering from the delusion that bugs form secondary to underlying psychological or physiologic are attacking their bodies, ES patients also experience conditions such as drug reaction or polypharmacy [5–8]. visual and tactile hallucinations that they see and feel the While Morgellons (“the fiber disease”) is likely a compo- bugs. ES patients exhibit a consistent complex of attributes nent on the same delusional spectrum, because it does not and behaviors that can adversely affect their lives. have entomologic connotations, it is not included in this discussion of ES [9, 10]. Keywords Parasitization . Parasitosis . Dermatozoenwahn . Valuable reviews of ES include those by Ekbom [1](1938), Invisible bugs . Ekbom syndrome . Bird mites . Infestation . Lyell [11] (1983), Trabert [12] (1995), and Bak et al. -

EMA Medical Terms Simplifier

EMA medical terms simplifier Plain-language description of medical terms related to medicines use polyuria petechiae tophi trismus idiopathic immunoglobulins acute antagonist An agency of the European Union 19 March 2021 EMA/158473/2021 EMA Medical Terms Simplifier Plain-language description of medical terms related to medicines use This compilation gives plain-language descriptions of medical terms commonly used in information about medicines. Communication specialists at EMA use these descriptions for materials prepared for the public. In our documents, we often adjust the description wordings to fit the context so that the writing flows smoothly without distorting the meaning. Since the main purpose of these descriptions is to serve our own writing needs, some also include alternative or optional wording to use as needed; we use ‘<>’ for this purpose. Our list concentrates on side effects and similar terms in summaries of product characteristics and public assessments of medicines but omits terms that are used only rarely. It does not include descriptions of most disease states or those that relate to specialties such as regulation, statistics and complementary medicine or, indeed, broader fields of medicine such as anatomy, microbiology, pathology and physiology. This resource is continually reviewed and updated internally, and we will publish updates periodically. If you have comments or suggestions, you may contact us by filling in this form. EMA Medical Terms Simplifier EMA/158473/2021 Page 1/76 A│B│C│D│E│F│G│H│I│J│K│L│M│N│O│P│Q│R│S│T│U│V│W│X│Y│Z -

Desquamation in the Stratum Corneum

Acta Derm Venereol 2000; Supp 208: 44±45 Desquamation in the Stratum Corneum TORBJOÈ RN EGELRUD Department of Public Health and Clinical Medicine, Dermatology and Venereology, UmeaÊ University, UmeaÊ, Sweden To maintain a constant thickness of the stratum corneum the In order to understand desquamation we will have to desquamation rate and the de novo production of corneocytes is identify mechanisms of cell cohesion in the stratum corneum, delicately balanced. Using a plantar stratum corneum model we the structures involved, and the changes these structures have obtained evidence that proteolysis is a central event in the undergo as cell cohesion decreases. We must then identify the desquamation process. A number of regulatory mechanisms for chemical reactions taking place, which would immediately desquamation have been postulated based on our ®ndings. give us information regarding the nature of the involved (Accepted September 20, 1999.) enzymes. Using pieces of plantar stratum corneum we have Acta Derm Venereol 2000; Supp 208: 44±45. developed a simple model system [1] in which some basic Professor TorbjoÈrn Egelrud, MD, Ph.D, Dept. events in desquamation can be studied. In addition to Dermatology, University of UmeaÊ, 90185, UmeaÊ, Sweden. information about the enzyme(-s) involved in stratum E-mail: [email protected] corneum cell dissociation, the system has provided informa- tion about the nature of the cohesive structures in the stratum corneum. An important ®nding was that corneocyte cohesion is mediated to a large extent by protein structures, i.e. the modi®ed desmosomes of the stratum corneum [2, 3]. This INTRODUCTION implied that proteolysis may be a central event in desquama- The building blocks of the stratum corneum, the corneocytes, tion. -

RASH in INFECTIOUS DISEASES of CHILDREN Andrew Bonwit, M.D

RASH IN INFECTIOUS DISEASES OF CHILDREN Andrew Bonwit, M.D. Infectious Diseases Department of Pediatrics OBJECTIVES • Develop skills in observing and describing rashes • Recognize associations between rashes and serious diseases • Recognize rashes associated with benign conditions • Learn associations between rashes and contagious disease Descriptions • Rash • Petechiae • Exanthem • Purpura • Vesicle • Erythroderma • Bulla • Erythema • Macule • Enanthem • Papule • Eruption Period of infectivity in relation to presence of rash • VZV incubates 10 – 21 days (to 28 d if VZIG is given • Contagious from 24 - 48° before rash to crusting of all lesions • Fifth disease (parvovirus B19 infection): clinical illness & contagiousness pre-rash • Rash follows appearance of IgG; no longer contagious when rash appears • Measles incubates 7 – 10 days • Contagious from 7 – 10 days post exposure, or 1 – 2 d pre-Sx, 3 – 5 d pre- rash; to 4th day after onset of rash Associated changes in integument • Enanthems • Measles, varicella, group A streptoccus • Mucosal hyperemia • Toxin-mediated bacterial infections • Conjunctivitis/conjunctival injection • Measles, adenovirus, Kawasaki disease, SJS, toxin-mediated bacterial disease Pathophysiology of rash: epidermal disruption • Vesicles: epidermal, clear fluid, < 5 mm • Varicella • HSV • Contact dermatitis • Bullae: epidermal, serous/seropurulent, > 5 mm • Bullous impetigo • Neonatal HSV • Bullous pemphigoid • Burns • Contact dermatitis • Stevens Johnson syndrome, Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis Bacterial causes of rash -

Sensitive Or Sensitized Skin

The New Age Spa Institute 1870 Busse Hwy, Des Plaines, IL 60016 847-759-0900 www.newagespainstitute.com Sensitive or Sensitized Skin SKIN PHYSIOLOGY The skin is made out of three major layers: Epidermis Dermis Subcutaneous Photo courtesy of Google Images Each layer plays an important role and it goes through many chemical reactions and physiological changes. Human skin is a beautiful yet very complex organ. Each layer undergoes through different stages in developing the top protective layer of our skin. The epidermis, the top most layer of skin, is only 0.1 to 1.5 millimeters thick. It is made up of five layers (starting from the deepest): • Stratum germinativum (basal) • Stratum spinosum (spiny) • Stratum granulosum (granular) • Stratum lucidum (clear) • Stratum corneum (horny) Working together, these layers continually rebuild the surface of the skin from within, maintaining the skin’s strength and protecting the internal organs of human’s body. 1 Basal Layer The process of cell regeneration begins in the basal layer of the epidermis. This layer comprises of small round cells called basal cells, which are considered the stem cells of the epidermis. Stem cells are biological cells that divide during process of cell mitosis and differentiate into specialized cells. Stem cells are self-renewing and producing new cells. The cells continually divide during the process of regeneration and push the older cells towards the top of the skin. This process is called Cell Turnover and it begins in the layer of stratum germinativum. The name germinativum refers to constant renewal or germination of new cells. There are various cells located within basal layer, but estheticians should have an understanding of at least two: • Melanocytes • Keratinocytes Melanocytes play important role within the skin. -

Newborn with Desquamating Rash

PHOTO ROUNDS Nataliya Holmes, MD; Jennifer J. Walker, MD, MPH; Newborn with desquamating Will Chapple, MD Hawaii Island Family Health Center, Hilo (Drs. Holmes and rash Walker); Paniolo Family Medicine, Kamuela (Dr. Chapple), Hawaii The patient’s age and the appearance of the lesions [email protected] pointed us to the proper diagnosis in this case. DEPARTMENT EDITOR Richard P. Usatine, MD University of Texas Health at San Antonio a 9-day-old boy was brought to the emergen- (FIGURE) with a small amount of dried sero- The authors reported no potential cy department by his mother. The infant had sanguinous drainage and similar superficial conflict of interest relevant to this article. been doing well until his most recent diaper peeling lesions at the left preauricular area and change when his mother noticed a rash around anterior chest. There was no underlying fluctu- the umbilicus (FIGURE), genitalia, and anus. ance and only minimal surrounding erythema. The infant was born at term via sponta- neous vaginal delivery. The pregnancy was ● WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS? uncomplicated; the infant’s mother was group B strep negative. Following a routine postpar- ● HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS tum course, the infant underwent an elective PATIENT? circumcision before hospital discharge on his second day of life. There were no interval re- ports of irritability, poor feeding, fevers, vomit- ing, or changes in urine or stool output. FIGURE The mother denied any recent unusual exposures, sick contacts, or travel. However, Peeling skin on temple and chest with upon further questioning, the mother not- erythematous rash at umbilical stump and genitalia ed that she herself had several small open wounds on the torso that she attributed to un- treated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). -

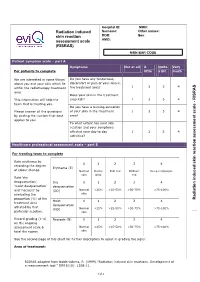

Risras) Mrn Bar Code

Hospital ID: MRN: Radiation induced Surname: Other names: skin reaction DOB: Sex: assessment scale AMO: (RISRAS) MRN BAR CODE Patient symptom scale – part A Symptoms Not at all A Quite Very For patients to complete little a bit much We are interested in some things Do you have any tenderness, about you and your skin which lie discomfort or pain of your skin in 1 2 3 4 within the radiotherapy treatment the treatment area? area. Does your skin in the treatment RISRAS This information will help the area itch? 1 2 3 4 - team that is treating you. Do you have a burning sensation Please answer all the questions of your skin in the treatment 1 2 3 4 cale s by circling the number that best area? applies to you. To what extent has your skin reaction and your symptoms affected your day to day 1 2 3 4 activities? ssessment a Healthcare professional assessment scale – part B eaction For treating team to complete r Rate erythema by kin 0 1 2 3 4 s recording the degree Erythema (E) of colour change. Normal Dusky Dull red Brilliant Deep red/purple skin pink red Rate ‘dry nduced i desquamation’, Dry 0 1 2 3 4 ‘moist desquamation’ desquamation and ‘necrosis’ by (DD) Normal <25% >25-50% >50-75% >75-100% evaluating the skin proportion (%) of the Radiation Moist 0 1 2 3 4 treatment area desquamation affected by that (MD) Normal <25% >25-50% >50-75% >75-100% particular reaction. skin Record grading (1-4) Necrosis (N) 0 1 2 3 4 on the ongoing assessment scale & Normal <25% >25-50% >50-75% >75-100% total the scores. -

Fever and Rash: Common Clinical Syndromes

Fever and Rash: Common clinical syndromes Christina Hermos, MD Primary Care Days April 10th, 2013 Westborough, MA Approach to Patient with Fever and Rash 1. Description of Rash 2. Associated Signs and Symptoms 3. Exposures Describe the Rash • Timing • Distribution – Where did it start? – Where has it spread? – Does it move (evanescent) or not (fixed)? • Symptoms – Itching – Pain – Swelling Describe the Rash Characteristics and common terminology • Type of lesion • Arrangement/shape – Macule (flat) – Scattered – Papule – Grouped – Nodule – Well demarcated – Vesicle – Morbilliform – Pustule – Coalescent – Abscess – Linear – Plaque – Annular – Wheal – Serpiginous • Color – Targetoid – Erythematous (red) – Lacey – Violacious (purple) • Consistency • Vascularity – Desquamation – Blanching – Sandpaper – Petechiae – Crust (scab) – Purpura – Ecchymosis Signs/Symptoms Associated with Rash • Fever duration and characteristics • Signs of shock – Hypotension, poor perfusion, decreased consciousness • Irritability • Headache • Respiratory symptoms • Eye changes • Mucous membrane lesions or pain • Joint pain or swelling Exposures • Sick contacts • Medications • Vaccines – Recent vaccines? – Incomplete suggesting susceptible host? • Daycare • Travel • Season • Outdoor exposures – Ticks, other vectors • Menses/Tampon use Case 1 •Diffuse •Erythematous •Blanching •“Erythroderma” •Sunburn Case 1 Associated signs/sxs Exposures • Fever: 40ºC, 1 day • Menses/Tampon use • Signs of shock: Yes • Headache • Injected bulbar conjunctiva • Hyperemic mucous membranes: • Dizzyness • Myalgias • Vomiting and diarrhea Toxic Shock Syndrome • Staphylococcus aureus – Menstrual and non-menstrual cases – Toxic shock syndrome toxin (TSST) and others – Bacteremia uncommon • Streptococcus pyogenes – TSS Complicates 1/3 of invasive GAS infections, most commonly necrotizing fasciitis – Bacteremia common Toxic Shock Syndrome in the United States: Surveillance Update, 1979–1996. • Hajjeh RA, Reingold A, Weil A, Shutt K, Schuchat A, Perkins BA. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. -

Part 4. Management of Acute Radiation-Induced Skin Toxicities

Practice Guideline: Symptom Management Part 4. Management of Acute Radiation-Induced Skin Toxicities Part 4 of a 5 Part Series: Evidence Based Recommendations for the Assessment and Management of Radiation-Induced Skin Toxicities in Breast Cancer Effective Date: January 2018 CancerCare Manitoba Guideline Symptom Management – Methodology for Radiation-Induced Skin Toxicities in Breast Cancer Series Developed by: Clinical Practice Guideline Adaptation Working Group CancerCare Manitoba Practice Guideline: Symptom Management| 2 Table of Contents Preface ................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Guideline Recommendations .............................................................................................................................. 4 Table 1. Management of Erythema, Pruritus and Dry Desquamation Promote Cleanliness .............................. 4 Table 2. Management of Erythema, Pruritus and Dry Desquamation Manage Pruritis ..................................... 4 Table 3. Management of Erythema, Pruritus and Dry Desquamation Promote Comfort .................................. 5 Table 4. Management of Erythema, Pruritus and Dry Desquamation Prevent Infection ................................... 5 Table 5. Management of Erythema, Pruritus and Dry Desquamation Protect From Trauma ............................ 6 Table 6. Management of Erythema, Pruritus and Dry Desquamation Promote Skin Health ............................ -

Desquamation

7 Desquamation Torbjörn Egelrud CONTENTS 7.1 Introduction.................................................................................. 71 7.2 Skin Diseases with Desquamation Disturbances .......................................... 72 7.3 Stratum Corneum Cell Dissociation Involves Proteolysis................................. 73 7.4 Desmosomes and Corneodesmosomes ..................................................... 73 7.5 Desquamation Involves Degradation of Corneodesmosomes ............................. 74 7.6 Enzymes Involved in Desquamation ....................................................... 75 7.7 Regulation of Desquamation ............................................................... 76 7.8 Conclusion................................................................................... 77 References ........................................................................................... 77 7.1 INTRODUCTION The stratum corneum is a cellular tissue. Its building blocks, the corneocytes, are highly resistant to physical and chemical trauma. The mechanical strength of an individual corneocyte, emanating from its tightly packed keratin bundles and the cross-linked proteins of the cornified envelope, is outstanding. The mechanical resistance of individual corneocytes is mirrored by the pronounced mechanical strength of the entire stratum corneum, implying a strong cell cohesion within the tissue. The corneocytes and their intercellular cohesive structures are prerequisites for the function of the stratum corneum as the physical–chemical