Twixt the Stone and the Turf – an Understanding of Gaelic Strength and Stone Lifting Peter J Martin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I. the Parallel Roads of Lochaber Have Presented to Geologists a Problem, Which Is Still Unsolved

(595) XXVII.—On the Parallel Roads of Lochaber. By DAVID MILNE HOME, LL.D, (Plates XLL, XLIL, XLIII.) (Read 15th May 1876.) I. The Parallel Roads of Lochaber have presented to geologists a problem, which is still unsolved. Dr MACCULLOCH, about sixty years ago, when President of the Geological Society of London, first called attention to these peculiar markings on the Lochaber Hills, by an elaborate Memoir afterwards published in that Society's Transactions. He was followed by Sir THOMAS DICK LAUDER, who in the year 1824, read a paper in our own Society, illustrated by excellent sketches. His paper is in our Transactions. The next author who attempted a solution was the present Mr CHARLES DARWIN. He maintained that these Roads were sea-beaches, formed, when this part of Europe was rising from beneath the Ocean. He was followed by Professor AGASSIZ, Dr BUCKLANB, CHARLES BABBAGE, Sir JOHN LUBBOCK, ROBERT CHAMBERS, Professor ROGERS, Sir GEORGE M'KENZIE, Mr JAMIESON of Ellon, Professor NICOL, Mr BRYCE of Glasgow, Mr WATSON, and Mr JOLLY of Inverness. Sir CHARLES LYELL, though he wrote no special memoir, treated the subject pretty fully in his works, giving an opinion in support of the views of AGASSIZ. I took some little part myself in the discussion, having in the year 1847 read a paper in this Society, which was published in our Transactions. During the last five or six years, there has been an entire cessation of both investigation and discussion, in consequence probably of a desire to await the publication of more correct maps of the district, which at the request of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, the Ordnance Survey Department undertook. -

A Survey of Leach's Petrels on Shetland in 2011

Contents Scottish Birds 32:1 (2012) 2 President’s Foreword K. Shaw PAPERS 3 The status and distribution of the Lesser Whitethroat in Dumfries & Galloway R. Mearns & B. Mearns 13 The selection of tree species by nesting Magpies in Edinburgh H.E.M. Dott 22 A survey of Leach’s Petrels on Shetland in 2011 W.T.S. Miles, R.M. Tallack, P.V. Harvey, P.M. Ellis, R. Riddington, G. Tyler, S.C. Gear, J.D. Okill, J.G Brown & N. Harper SHORT NOTES 30 Guillemot with yellow bare parts on Bass Rock J.F. Lloyd & N. Wiggin 31 Reduced breeding of Gannets on Bass Rock in 2011 J. Hunt & J.B. Nelson 32 Attempted predation of Pink-footed Geese by a Peregrine D. Hawker 32 Sparrowhawk nest predation by Carrion Crow - unique footage recorded from a nest camera M. Thornton, H. & L. Coventry 35 Black-headed Gulls eating Hawthorn berries J. Busby OBITUARIES 36 Dr Raymond Hewson D. Jenkins & A. Watson 37 Jean Murray (Jan) Donnan B. Smith ARTICLES, NEWS & VIEWS 38 Scottish seabirds - past, present and future S. Wanless & M.P. Harris 46 NEWS AND NOTICES 48 SOC SPOTLIGHT: the Fife Branch K. Dick, I.G. Cumming, P. Taylor & R. Armstrong 51 FIELD NOTE: Long-tailed Tits J. Maxwell 52 International Wader Study Group conference at Strathpeffer, September 2011 B. Kalejta Summers 54 Siskin and Skylark for company D. Watson 56 NOTES AND COMMENT 57 BOOK REVIEWS 60 RINGERS’ ROUNDUP R. Duncan 66 Twelve Mediterranean Gulls at Buckhaven, Fife on 7 September 2011 - a new Scottish record count J.S. -

Frommer's Scotland 8Th Edition

Scotland 8th Edition by Darwin Porter & Danforth Prince Here’s what the critics say about Frommer’s: “Amazingly easy to use. Very portable, very complete.” —Booklist “Detailed, accurate, and easy-to-read information for all price ranges.” —Glamour Magazine “Hotel information is close to encyclopedic.” —Des Moines Sunday Register “Frommer’s Guides have a way of giving you a real feel for a place.” —Knight Ridder Newspapers About the Authors Darwin Porter has covered Scotland since the beginning of his travel-writing career as author of Frommer’s England & Scotland. Since 1982, he has been joined in his efforts by Danforth Prince, formerly of the Paris Bureau of the New York Times. Together, they’ve written numerous best-selling Frommer’s guides—notably to England, France, and Italy. Published by: Wiley Publishing, Inc. 111 River St. Hoboken, NJ 07030-5744 Copyright © 2004 Wiley Publishing, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval sys- tem or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo- copying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978/750-8400, fax 978/646-8600. Requests to the Publisher for per- mission should be addressed to the Legal Department, Wiley Publishing, Inc., 10475 Crosspoint Blvd., Indianapolis, IN 46256, 317/572-3447, fax 317/572-4447, E-Mail: [email protected]. -

THE MYTHOLOGY, TRADITIONS and HISTORY of Macdhubhsith

THE MYTHOLOGY, TRADITIONS and HISTORY OF MacDHUBHSITH ― MacDUFFIE CLAN (McAfie, McDuffie, MacFie, MacPhee, Duffy, etc.) VOLUME 2 THE LANDS OF OUR FATHERS PART 2 Earle Douglas MacPhee (1894 - 1982) M.M., M.A., M.Educ., LL.D., D.U.C., D.C.L. Emeritus Dean University of British Columbia This 2009 electronic edition Volume 2 is a scan of the 1975 Volume VII. Dr. MacPhee created Volume VII when he added supplemental data and errata to the original 1792 Volume II. This electronic edition has been amended for the errata noted by Dr. MacPhee. - i - THE LIVES OF OUR FATHERS PREFACE TO VOLUME II In Volume I the author has established the surnames of most of our Clan and has proposed the sources of the peculiar name by which our Gaelic compatriots defined us. In this examination we have examined alternate progenitors of the family. Any reader of Scottish history realizes that Highlanders like to move and like to set up small groups of people in which they can become heads of families or chieftains. This was true in Colonsay and there were almost a dozen areas in Scotland where the clansman and his children regard one of these as 'home'. The writer has tried to define the nature of these homes, and to study their growth. It will take some years to organize comparative material and we have indicated in Chapter III the areas which should require research. In Chapter IV the writer has prepared a list of possible chiefs of the clan over a thousand years. The books on our Clan give very little information on these chiefs but the writer has recorded some probable comments on his chiefship. -

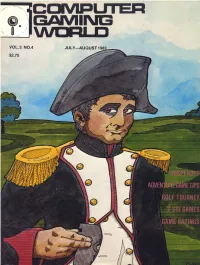

Computer Gaming World Issue

I - Vol. 3 No. 4 Jul.-Aug. - 1983 FEATURES SUSPENDED 10 The Cryogenic Nightmare David P. Stone M.U.L.E. 12 One of Electronic Arts' New Releases Edward Curtis BATTLE FOR NORMANDY 14 Strategy and Tactics Jay Selover SCORPION'S TALE 16 Adventure Game Hints and Tips Scorpia COSMIC BALANCE CONTEST WINNER 17 Results of the Ship Design Contest KNIGHTS OF THE DESERT 18 Review Gleason & Curtis GALACTIC ADVENTURES 20 Review & Hints David Long COMPUTER GOLF! 29 Four Games Reviewed Stanley Greenlaw BOMB ALLEY 35 Review Richard Charles Karr THE COMMODORE KEY 42 A New Column Wilson & Curtis Departments Inside the Industry 4 Hobby and Industry News 5 Taking a Peek 6 Tele-Gaming 22 Real World Gaming 24 Atari Arena 28 Name of the Game 38 Silicon Cerebrum 39 The Learning Game 41 Micro-Reviews 43 Reader Input Device 51 Game Ratings 52 Game Playing Aids from Computer Gaming World COSMIC BALANCE SHIPYARD DISK Contains over 20 ships that competed in the CGW COSMIC BALANCE SHIP DESIGN CONTEST. Included are Avenger, the tournament winner; Blaze, Mongoose, and MKVP6, the judge's ships. These ships are ideal for the gamer who cannot find enough competition or wants to study the ship designs of other gamers around the country. SSI's The Cosmic Balance is required to use the shipyard disk. PLEASE SPECIFY APPLE OR ATARI VERSION WHEN ORDERING. $15.00 ROBOTWAR TOURNAMENT DISK CGW's Robotwar Diskette contains the source code for the entrants to the Second Annual CGW Robotwar Tournament (with the exception of NordenB) including the winner, DRAGON. -

Dragon Magazine

May 1980 The Dragon feature a module, a special inclusion, or some other out-of-the- ordinary ingredient. It’s still a bargain when you stop to think that a regular commercial module, purchased separately, would cost even more than that—and for your three bucks, you’re getting a whole lot of magazine besides. It should be pointed out that subscribers can still get a year’s worth of TD for only $2 per issue. Hint, hint . And now, on to the good news. This month’s kaleidoscopic cover comes to us from the talented Darlene Pekul, and serves as your p, up and away in May! That’s the catch-phrase for first look at Jasmine, Darlene’s fantasy adventure strip, which issue #37 of The Dragon. In addition to going up in makes its debut in this issue. The story she’s unfolding promises to quality and content with still more new features this be a good one; stay tuned. month, TD has gone up in another way: the price. As observant subscribers, or those of you who bought Holding down the middle of the magazine is The Pit of The this issue in a store, will have already noticed, we’re now asking $3 Oracle, an AD&D game module created by Stephen Sullivan. It for TD. From now on, the magazine will cost that much whenever we was the second-place winner in the first International Dungeon Design Competition, and after looking it over and playing through it, we think you’ll understand why it placed so high. -

Erin and Alban

A READY REFERENCE SKETCH OF ERIN AND ALBAN WITH SOME ANNALS OF A BRANCH OF A WEST HIGHLAND FAMILY SARAH A. McCANDLESS CONTENTS. INTRODUCTION. PART I CHAPTER I PRE-HISTORIC PEOPLE OF BRITAIN 1. The Stone Age--Periods 2. The Bronze Age 3. The Iron Age 4. The Turanians 5. The Aryans and Branches 6. The Celto CHAPTER II FIRST HISTORICAL MENTION OF BRITAIN 1. Greeks 2. Phoenicians 3. Romans CHAPTER III COLONIZATION PE}RIODS OF ERIN, TRADITIONS 1. British 2. Irish: 1. Partholon 2. Nemhidh 3. Firbolg 4. Tuatha de Danan 5. Miledh 6. Creuthnigh 7. Physical CharacteriEtics of the Colonists 8. Period of Ollaimh Fodhla n ·'· Cadroc's Tradition 10. Pictish Tradition CHAPTER IV ERIN FROM THE 5TH TO 15TH CENTURY 1. 5th to 8th, Christianity-Results 2. 9th to 12th, Danish Invasions :0. 12th. Tribes and Families 4. 1169-1175, Anglo-Norman Conquest 5. Condition under Anglo-Norman Rule CHAPTER V LEGENDARY HISTORY OF ALBAN 1. Irish sources 2. Nemedians in Alban 3. Firbolg and Tuatha de Danan 4. Milesians in Alban 5. Creuthnigh in Alban 6. Two Landmarks 7. Three pagan kings of Erin in Alban II CONTENTS CHAPTER VI AUTHENTIC HISTORY BEGINS 1. Battle of Ocha, 478 A. D. 2. Dalaradia, 498 A. D. 3. Connection between Erin and Alban CHAPTER VII ROMAN CAMPAIGNS IN BRITAIN (55 B.C.-410 A.D.) 1. Caesar's Campaigns, 54-55 B.C. 2. Agricola's Campaigns, 78-86 A.D. 3. Hadrian's Campaigns, 120 A.D. 4. Severus' Campaigns, 208 A.D. 5. State of Britain During 150 Years after SeveTus 6. -

Debtbook Diplomacy China’S Strategic Leveraging of Its Newfound Economic Influence and the Consequences for U.S

POLICY ANALYSIS EXERCISE Debtbook Diplomacy China’s Strategic Leveraging of its Newfound Economic Influence and the Consequences for U.S. Foreign Policy Sam Parker Master in Public Policy Candidate, Harvard Kennedy School Gabrielle Chefitz Master in Public Policy Candidate, Harvard Kennedy School PAPER MAY 2018 Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs Harvard Kennedy School 79 JFK Street Cambridge, MA 02138 www.belfercenter.org Statements and views expressed in this report are solely those of the authors and do not imply endorsement by Harvard University, the Harvard Kennedy School, or the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. This paper was completed as a Harvard Kennedy School Policy Analysis Exercise, a yearlong project for second-year Master in Public Policy candidates to work with real-world clients in crafting and presenting timely policy recommendations. Design & layout by Andrew Facini Cover photo: Container ships at Yangshan port, Shanghai, March 29, 2018. (AP) Copyright 2018, President and Fellows of Harvard College Printed in the United States of America POLICY ANALYSIS EXERCISE Debtbook Diplomacy China’s Strategic Leveraging of its Newfound Economic Influence and the Consequences for U.S. Foreign Policy Sam Parker Master in Public Policy Candidate, Harvard Kennedy School Gabrielle Chefitz Master in Public Policy Candidate, Harvard Kennedy School PAPER MARCH 2018 About the Authors Sam Parker is a Master in Public Policy candidate at Harvard Kennedy School. Sam previously served as the Special Assistant to the Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs at the Department of Homeland Security. As an academic fellow at U.S. Pacific Command, he wrote a report on anticipating and countering Chinese efforts to displace U.S. -

Twixt Ocean and Pines : the Seaside Resort at Virginia Beach, 1880-1930 Jonathan Mark Souther

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 5-1996 Twixt ocean and pines : the seaside resort at Virginia Beach, 1880-1930 Jonathan Mark Souther Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Souther, Jonathan Mark, "Twixt ocean and pines : the seaside resort at Virginia Beach, 1880-1930" (1996). Master's Theses. Paper 1037. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TWIXT OCEAN AND PINES: THE SEASIDE RESORT AT VIRGINIA BEACH, 1880-1930 Jonathan Mark Souther Master of Arts University of Richmond, 1996 Robert C. Kenzer, Thesis Director This thesis descnbes the first fifty years of the creation of Virginia Beach as a seaside resort. It demonstrates the importance of railroads in promoting the resort and suggests that Virginia Beach followed a similar developmental pattern to that of other ocean resorts, particularly those ofthe famous New Jersey shore. Virginia Beach, plagued by infrastructure deficiencies and overshadowed by nearby Ocean View, did not stabilize until its promoters shifted their attention from wealthy northerners to Tidewater area residents. After experiencing difficulties exacerbated by the Panic of 1893, the burning of its premier hotel in 1907, and the hesitation bred by the Spanish American War and World War I, Virginia Beach enjoyed robust growth during the 1920s. While Virginia Beach is often perceived as a post- World War II community, this thesis argues that its prewar foundation was critical to its subsequent rise to become the largest city in Virginia. -

Why Donegal Slept: the Development of Gaelic Games in Donegal, 1884-1934

WHY DONEGAL SLEPT: THE DEVELOPMENT OF GAELIC GAMES IN DONEGAL, 1884-1934 CONOR CURRAN B.ED., M.A. THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PH.D. THE INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR SPORTS HISTORY AND CULTURE AND THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORICAL AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES DE MONTFORT UNIVERSITY LEICESTER SUPERVISORS OF RESEARCH: FIRST SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR MATTHEW TAYLOR SECOND SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR MIKE CRONIN THIRD SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR RICHARD HOLT APRIL 2012 i Table of Contents Acknowledgements iii Abbreviations v Abstract vi Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Donegal and society, 1884-1934 27 Chapter 2 Sport in Donegal in the nineteenth century 58 Chapter 3 The failure of the GAA in Donegal, 1884-1905 104 Chapter 4 The development of the GAA in Donegal, 1905-1934 137 Chapter 5 The conflict between the GAA and association football in Donegal, 1905-1934 195 Chapter 6 The social background of the GAA 269 Conclusion 334 Appendices 352 Bibliography 371 ii Acknowledgements As a rather nervous schoolboy goalkeeper at the Ian Rush International soccer tournament in Wales in 1991, I was particularly aware of the fact that I came from a strong Gaelic football area and that there was only one other player from the south/south-west of the county in the Donegal under fourteen and under sixteen squads. In writing this thesis, I hope that I have, in some way, managed to explain the reasons for this cultural diversity. This thesis would not have been written without the assistance of my two supervisors, Professor Mike Cronin and Professor Matthew Taylor. Professor Cronin’s assistance and knowledge has transformed the way I think about history, society and sport while Professor Taylor’s expertise has also made me look at the writing of sports history and the development of society in a different way. -

The Cairngorm Club Journal 104, 1996

231 HUTS, HOSTELS AND BUNKHOUSES Bookings for huts belonging to other clubs are often only accepted through our Club Secretary. BH Bunkhouse OC Outdoor Centre IH Independent Hostel SC Self Catering + Group bookings only * No cooking facilities BIGGAR Netherurd House, Biggar + IH 01968 682208 GLASGOW Backpackers Hostel IH 0141 332 5412 EDINBURGH High Street Hostel IH 0131 557 3984 Backpackers, Royal Mile IH 0131 557 6120 Belford Youth Hostel IH 0131 225 6209 Princes Street Hostel IH 0131 556 6894 Cowgate Tourist Hostel IH 0131 226 2153 Backpackers Hostel IH 0131 220 1717 FIFE Anstruther Bunkhouse IH 01333 310768 ARROCHAR The Old Stables, East Kilbride M.C. Hut Glen Croe, 8 Miles High M.C. Hut 01592 714354 OBAN Jeremy Inglis IH 01631 565065 Oban Backpackers IH 01631 562107 CRIANLARICH Ochils M.C. Hut 01259 217123 CRIEFF Braincroft Bunkhouse BH 01764 670140 AUCH MacDougalls Cottage, Clachaig M.C. Hut 0141 334 8871 BRIDGE OF ORCHY The Way Inn * BH 01838 400208/209 Glencoe Ski Club Lodge Hut 0141 623 5317 FOREST LODGE Clashgour,Glasgow University M.C. Hut 01360311917 GLEN ETIVE Inbhirfhaolain, Grampian Club Hut via huts custodian The Smiddy, Forventure Hut 0141 959 9965 GLENCOE Black Rock Cottage, L.S.C.C. Hut 0141 956 1201 Kingshouse Hotel BH 01855 851259 Lagangarbh. S.M.C. Hut 01389 731917 Leacantium Farm BH 01855 811256 Clachaig Inn BH 01855 811252 Kyle M.C. Memorial Hut TheKINLOCHLEVE NCairngorm West Highland Lodge B H Club018554 831471 Mamore Lodge + BH 01855 831213 Rose Cottage BH 01855 831471/396 ONICH Manse Barn. Lomond M.C. -

The Civilizing and Sportization of Gaelic Football in Ireland: 1884–2009

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Articles Centre for Consumption and Leisure Studies 2010 The Civilizing and Sportization of Gaelic Football in Ireland: 1884–2009 John Connolly Dublin City University Paddy Dolan Technological University Dublin, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/clsart Part of the Sociology Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Connolly, J. & Dolan, P. (2010) ‘The Civilizing and Sportization of Gaelic Football in Ireland: 1884–2008’, Journal of Historical Sociology vol. 23, no.4, pp 570–98. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6443.2010.01384.x This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Centre for Consumption and Leisure Studies at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License Authors: John Connolly and Paddy Dolan Title: The Civilizing and Sportization of Gaelic Football in Ireland: 1884–2009 Originally published in Journal of Historical Sociology 23(4): 570–98. Copyright Wiley. The publisher’s version is available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1467-6443.2010.01384.x/abstract Please cite the publisher’s version: Connolly, John and Paddy Dolan (2010) ‘The civilizing and sportization of Gaelic football in Ireland: 1884–2008’, Journal of Historical Sociology 23(4): 570–98. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-6443.2010.01384.x This document is the authors’ final manuscript version of the journal article, incorporating any revisions agreed during peer review.